How to Cite: Ariza Parrado, Lucas. "Temporality in Architecture: A Matter of Rhythm. Parque Prado Centro, Medellín, Colombia". Dearq no. 43 (2025): 8-17. DOI: https://doi.org/10.18389/dearq43.2025.02

How to Cite: Ariza Parrado, Lucas. "Temporality in Architecture: A Matter of Rhythm. Parque Prado Centro, Medellín, Colombia". Dearq no. 43 (2025): 8-17. DOI: https://doi.org/10.18389/dearq43.2025.02

Lucas Ariza Parrado

Universidad de los Andes, Colombia

Received: August 28, 2024 | Accepted: March 19, 2025

This article explores the temporal dimension of architecture by examining the apparent contradiction between the ephemeral and the permanent. It considers rhythm as the fundamental structure through which time is expressed: matter carries its own intrinsic rhythm, and architecture proposes a rhythm through which life is lived. If our understanding of duration shifts depending on the frame of reference, then perhaps all architecture is, at its core, temporal. These reflections are grounded in a case study that is particularly resonant in terms of its construction, occupation, and interpretation of the life cycle: Parque Prado Centro in Medellín, Colombia.

Keywords: Rhythm, body, gesture, habit, time, Parque Prado Centro.

Architecture does not happen in time. Time happens in architecture.

— Josep Quetglas, "La danza y la procesión"

Architecture is a discipline that is not only spatial, but also inherently temporal—an idea widely recognized and supported from multiple perspectives. Time, for example, acts as an architect in its own right, shaping and reshaping spaces as profoundly as those who design and build them. It may also be understood as a material—one that contributes to both the creation of architecture and its eventual dissolution. Architecture is not merely something we occupy in space; it is something we experience through time: traversed, unveiled, and sensed as it unfolds. Building on these established ideas, this article proposes that our experience of time is mediated by the rhythms we perceive through gestures and bodily movements in relation to both built and natural environments.

In a 1994 essay on the architecture of Rafael Moneo, Spanish architect and theorist Josep Quetglas identifies three ways in which time becomes perceptible in architecture. One of these involves the ability to hold all possible times within a single instant—like a dancer who, with grace, momentarily freezes in place. Quetglas elaborates on this notion of time, stating that "Another model is possible, one that resists spatial metaphors—not a river, not a wheel. It is a model found in the work of poets, prophets, and revolutions, where each instant bears the weight of all previously lived moments. Each moment presents and makes present the entirety of time"1(1994, 33).

In light of this, it is worth revisiting the etymology of the word time, which "is derived from two Greek verbs, with two opposite meanings. The first, témnô, means to cut, while the other, teinô, means to stretch. The former refers to breaks used to distinguish epochs in historical periodization, while the latter conveys the image of continuous flow" (Serres 1996, 35). This article draws on the concept of rhythm to further explore time, aiming to interrogate yet another contradiction—or perhaps the same one—between the fleeting and the enduring. Architecture establishes a layered relationship between the rhythm of the body—seemingly ephemeral, yet persistent in every breathing being—and that of the world around it, which appears permanent, yet is in constant flux: no repetition is ever identical, and only change truly endures.

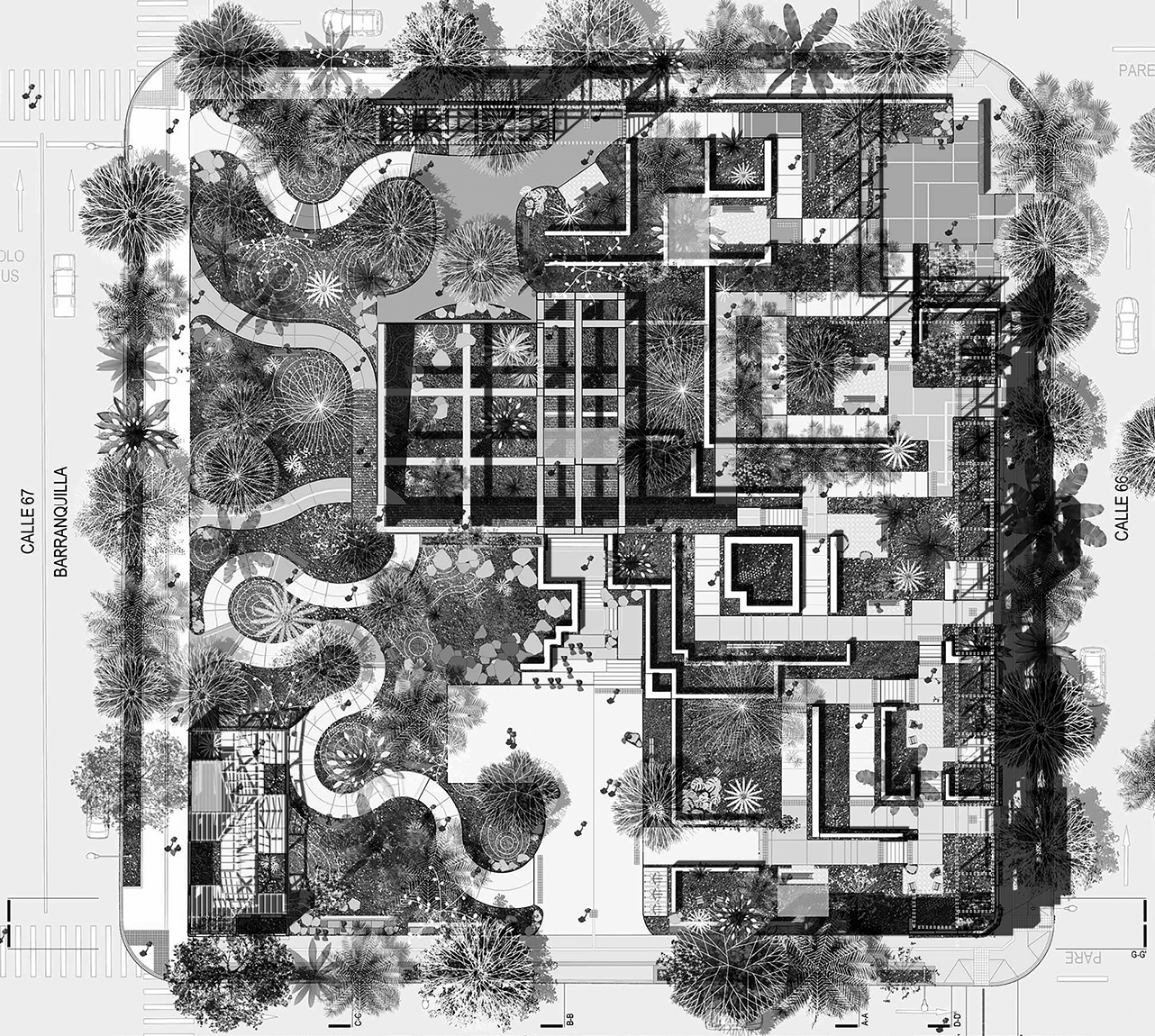

Parque Prado Centro (fig. 1) serves as the case study through which this article explores a temporal understanding of architecture. The project is particularly relevant for several reasons. Its design emphasizes the importance of open space and human-scale proportions, while giving prominence to preexisting topographic (ground) and atmospheric (sky) conditions. Its construction and life cycle involved not only the creation of new structures, but also the careful dismantling and preservation of what previously stood, alongside the emergence of new spatial conditions. Its occupation fosters a form of dwelling attuned to the everyday gestures and rhythms of those who live in the area, including long-standing residents who were there even before the park came into being. Located in Aranjuez,2 one of Medellín's sixteen comunas, the park was built in 2021 by the Urban Development Corporation (EDU) and designed by Colombian architect Edgar Mazo Zapata.3

Figure 1_ Orthophotograph of Parque Prado Centro. Source: Connatural Architecture in the Landscape archive.

The park sits on an almost square plot with a gentle slope—an element that informed several of the project's key design intentions. Prior to the intervention, the site bore clear signs of abandonment (fig. 2): "The area was in a state of disrepair, with a few standing structures overtaken by vegetation along its southern edge, and surrounded by vacant lots and scattered building remnants" (Charum, Mejía & Havik 2022, 83). From the outset, the project defined a series of deliberate strategies to ensure a construction process that could unfold and endure over time. First, only select elements—such as concrete slabs and brick walls—were carefully dismantled, guided by principles of deconstruction material reuse. Second, the design incorporated permeable terraces that filter urban runoff while hosting native plant species, thereby attracting both human and non-human life in overlapping rhythms. Finally, the revival of vernacular construction techniques reintroduced a sense of temporality rooted in the manual labor of the local community. Together, these strategies propose an approach to architecture in which the ephemeral and the permanent are not opposing forces, but intertwined modes of existing in time.

Figure 2_ Site conditions prior to intervention. Source: Connatural Architecture in the Landscape archive.

The project is conceived as open architecture—welcoming to all and ready to be experienced at any moment. There are no gates or fences enforcing exclusion. Instead, it offers a space that does not merely exist but comes into being through movement—when someone passes through it, and when, through the lightness of gesture, a relationship with the space begins. Materiality, scale, shifts in level, and the proportions and edges of the block all contribute to the project's capacity to reveal itself in multiple ways. At times, it takes the form of a park—an oasis where nature asserts its presence. At others, it becomes a garden, allowing domestic life to flow gently into the city without rigid boundaries. It can transform into a plaza or stage—an agora where expression and encounter unfold, a space to see and be seen (fig. 3). As Colombian architect Carlos Mesa notes in his reflections on the Aranjuez comuna, the built elements of the park—those seemingly more permanent—are interwoven with human gestures and actions that, though often considered fleeting, leave a lasting trace.

Figure 3_ Architectural site plan. Source: Connatural Architecture in the Landscape archive.

The space defined by the park is partially framed by a sequence of façades—fragile shells that still echo the proportions and dimensions of a neighborhood shaped gradually, spontaneously, and by hand. At the same time, the park opens outward—through doors and windows, or through the hollow outlines where they once were—becoming a spectral presence, something simultaneously there and not there (fig. 4). The project embraces a powerful contradiction: it encloses and expands at the same time, not only in spatial terms but in temporal ones as well. As Quetglas suggests, the present can contain all possible times—as if time itself were an event that unfolds in space. The past reverberates through every fragment now sustained by the new structure, while the future emerges with each step—a latent force bearing everything that once disappeared. Our experience is always one of inhabiting, moment by moment, the enchantment of rhythm—an eternal return to origins that opens onto the future" (Sini 1993, 64). Viewed in this light, the dichotomy between the ephemeral and the permanent is not merely dissolved, but reimagined.

Figure 4_ Pre-existing façades that now form part of the park. Source: Catalina Villabona.

But it is the ballroom with its tiled floor and its paneling, the stairs in the background and the lion's paw at the side which creates the film's dense, powerful atmosphere. Or is it the other way round? Is it the people who endow the room with its particular mood? I ask this question because I am convinced that a good building must be capable of absorbing the traces of human life and thus of taking on a specific richness.

— Peter Zumthor, Thinking Architecture

In this brief but compelling passage, Swiss architect Peter Zumthor (2006, 24) poses a question that invites deeper reflection on the temporality of architecture. To fully engage with this dimension, it becomes essential to pause and consider rhythm—not only as the underlying structure of time, but also as a vital condition for the formation of habits that shape and sustain architectural experience.

Rhythm in architecture is often understood through compositional elements—the cadence of forms, the repetition of structures, the measured alignment of spaces. Indeed, rhythm is embedded in the physical fabric of what architecture constructs. Yet another rhythm is equally present: that of those who inhabit architecture, who activate it and infuse it with memory and meaning through their daily gestures. While material and compositional rhythms delineate the physical contours of space—what we tend to perceive as enduring—gestural rhythms, repeated over time, transform seemingly ephemeral actions into habits and rituals, inscribing architecture with its own lived temporality.

Material Rhythm

To explore this question more deeply, we begin with the material—with the constructed reality, the physical body of architecture, and its relationship to time. It is through the delineation of certain boundaries that relationships between beings and things are made possible, allowing places to emerge. As Finnish architect Juhani Pallasmaa notes, "Architecture initiates, directs, and structures behavior and movement" (2014, 75).

When considering the physical dimension of architecture—its material presence—it becomes essential to reflect on the idea of measurement. In relation to rhythm and time, measurement is a foundational concept: it situates the individual in between—between earth, sky, and other beings. As De Molina (2016) writes, "From distance arises the magic of a thing's proper measure; from measure comes the understanding of relationships among things; from these relationships, rhythm emerges—and from rhythm, the meaning of structure, construction, and even form." Measurement, on its own, holds no intrinsic meaning; it is only through relationships that meaning begins to take shape. Through these relational dynamics, we begin to grasp the sensations produced by proportion—proportion that allows the body to orient itself in the world.

Rhythm resides in matter, regardless of its form. In other words, matter takes shape through an inherent rhythm—evident in the ways it is arranged, assembled, or revealed. This becomes particularly tangible in Parque Prado Centro. The dismantling of existing structures introduced a tempo distinct from that of demolition—a rhythm closer to that of careful reordering or relocation. The site's preexisting elements—industrial buildings and homes—remain partially intact, preserving their original rhythms, though now stripped of their former configurations (fig. 5). Some structures still stand, supported by porticoed frameworks; others endure only in memory, evoked by the material itself. Clay tiles, bricks, and wooden beams remain, tracing the outlines of what once was. These elements preserve latent relationships—precise intervals and spatial logics—reconfigured to offer a renewed presence. Matter endures: transformed, yet still resonant.

Figure 5_ Walls made with reused materials. Source: Isaac Ramírez.

Much like the built environment, nature plays a vital role in the project. The site's preexisting vegetation—emerging during a period of abandonment in what French architect and gardener Gilles Clément (2007) describes as a "third landscape"—was complemented by a carefully selected array of diverse and evocative plant species. Together, they form a park that invites not only human presence, but also that of other forms of life. The rhythms of nature introduce a distinct temporality to the project—one shaped by cycles, yet animated by the unpredictable vitality of all living things. In this convergence, the boundaries between the natural and the cultural begin to blur. Perhaps one of the project's quiet aspirations is to question yet another division: the one that separates nature from culture. The rhythm set by nature meets the rhythm proposed by humans—each finding resonance in the other.

Within this interplay, the park takes shape: a fragmented perimeter structure, partially ruined and altogether absent in some sections, which dissolves once inside the defined space, blending seamlessly into its surroundings. Here, the boundary is not dictated by necessity or rigid form; instead, it becomes an invitation—one that allows for a multitude of possibilities. Japanese architect Sou Fujimoto offers a fitting analogy: "Japanese kimonos do not follow the contours of the human body; instead, they trace its infinite movements. In a sense, they design the air around the body—they shape the interaction between garment and gesture" (2010, 211).

Gestural Rhythm

Places are contingent; they take shape through the presence of each body that inhabits them. This section shifts focus to the actions performed by those bodies. Broadly speaking, such actions can be grouped into two categories. The first are instrumental actions—those undertaken as a means to achieve something else, with their purpose lying beyond the act itself. The second are gratuitous actions—performed not for an external outcome, but for the experience they offer to the person enacting them. These are pure means: actions whose value resides entirely in the act itself.

A gesture can be understood as one of those actions that function as pure means—an embodied expression of rhythm through which the passage of time becomes perceptible. Some gestures are subtle, almost imperceptible; others leave a marked imprint on both the body and its surroundings. Architecture has the capacity to recognize gesture as a fleeting fragment of time—transient and unfixed, yet capable of holding multiple temporalities. A gesture can activate a space, summon memory, and revive ways of doing that appear new only because they were once forgotten. In this way, the immediacy of a gesture contains a temporality far richer than the instant it occupies.

If architecture were to truly attend to gesture, it might open the door to a daily rediscovery of how we inhabit space—guided by a deep, embodied memory, the kind that remembers even before it knows. As Santiago de Molina (2023) observes, "Each inhabitant does what they can. […] No one inhabits poorly if no one knows what it means to inhabit well." Gesture carries within it the potential to reframe and reimagine the built world (fig. 6).

Figure 6_ Leaning on the park's balcony. Source: Isaac Ramírez.

Thus, Parque Prado Centro responds to actions that carry meaning in and of themselves—actions that form part of shared, embodied habits. The park becomes an urban pause, one that slows the rhythm of life without bringing it to a halt. Some move through it, traversing its interconnected levels; others pause briefly, adjust their pace, and—leaning on the urban balcony, feet firmly grounded—allow their gaze to stretch toward the horizon. "The intensity of a brief experience, the feeling of being utterly suspended in time, beyond past and future—this belongs to many, perhaps even to all sensations of beauty […] Everything is itself. The flow of time has been halted, experience crystallized into an image whose beauty seems to indicate depth" (Zumthor 2006, 72).

The park invites gestures rarely associated with public space—gestures that evoke the intimacy of home. These symbolic actions reawaken rhythms that, through repetition, have become unconscious or automatic. In its southwestern corner, the park offers a contemplative view of the city, framed by what was once a window in a house and is now nothing more than an opening in a fragile wall. Though the view is shared, it is framed with the tenderness of the domestic, shaped by the quiet cadence of everyday life.

To pass through a façade now propped up by a metal brace—a structure that quietly signals it is no longer what it once was—and to enter the park through a domestic doorway is to recognize that while the body's gestures persist, and the rhythm of our steps endures, the meanings they carry have shifted.

The park weaves together a sense of intimacy—reminiscent of a quiet backyard—with a feeling of connection to an ecological system that extends beyond the boundaries of the plot and the city, reaching into the broader landscape. Within this ruin-like enclosure, nature assumes a new character—domesticated by the remnants of what once constituted a neighborhood. It becomes a symbolic monument to the art of memory (Marot 2006)—a project that feels as though it has always been there, and one that may never be truly complete, as it continues to evolve with each passing day. Here, time takes on a completely different dimension and becomes a time of remembrance, of shared daily life, of collective belonging (fig. 7).

Figure 7_ Resting in the park. Source: Author's archives.

Throughout this text, the duality between the ephemeral and the permanent has been examined from multiple perspectives. The argument proposed is that this distinction is far from absolute. Rather, it is possible to conceive that both temporalities—the fleeting and the enduring—coexist within all architecture. Duration is always relative, anchored to our own existence, which often pales in comparison to the lifespans of other beings and materials that inhabit the world alongside us. Italian sculptor Giuseppe Penone expresses this idea with striking clarity: "To me, all elements are fluid. Even stone is fluid—a mountain crumbles, becomes sand. It is only a matter of time. It is the brief span of our existence that leads us to call one material 'hard' and another 'soft.' Time dissolves these categories."(Penone, 1978, cited in Didi-Huberman, 2008, 49).

Questioning whether architecture can be neatly classified as either ephemeral or permanent reveals that the real challenge lies not in choosing between these categories, but in navigating the relationship between their overlapping temporalities. What kind of temporal interplay unfolds between the platforms and ruined façades of Parque Prado Centro and the introspective or practical gestures that take place within its bounds? The material qualities of these boundaries—weight, scale, texture, patina, stability, porosity—imbue the space with distinct characteristics, allowing it to be experienced as a lived space, "a space attuned less to reason than to the heart" (Merleau-Ponty 2002, 22). The air enclosed within seems to carry a subtle charge, as if gently stirred,4 giving the park a singular atmosphere—one in which entering becomes a way of stepping outward, into a realm where time is felt rather than counted; a temporality that precedes us and will continue long after we are gone (fig. 8).

Figure 8_ The charged atmosphere of the park. Source: Isaac Ramírez.

It is a space that feels charged, attuned, and delicately held in tension—where the various rhythms explored throughout this text, expressed through gestures and actions, begin to resonate. Just as a musician vibrates with their instrument in every note, space too can be attuned—its relationships arranged and stretched into rhythm—to create an atmosphere for inhabiting. "But when I close my eyes and try to forget these physical traces and my own first associations, what remains is a different impression, a deeper feeling–a consciousness of time passing and an awareness of the human lives that have been acted out in these places and rooms and charged them with a special aura" (Zumthor 2006, 25).

German architectural theorist Hugo Häring, in distinguishing choreographic architecture from prosthetic architecture—where space is designed for clearly defined functions and form is conceived as immediate, almost timeless—states that "the space in which living beings move and carry out their lives is a space of events" (Quesada 2010, 92). Viewed in this light, architecture is inherently aligned with temporality. It is shaped not only by grand or spectacular events, but also by fleeting illuminations within the everyday. Architecture reveals the world, transforms space into place, and in doing so, gives form to actions, behaviors, emotions, and relationships.

"Perhaps that was the only thing that interested me about architecture: I knew it was the result of a struggle between time and a form that would ultimately be destroyed in the fight. Architecture was one of the ways humanity had sought survival—a way to express its essential pursuit of happiness" (Rossi 1998, 10).

As Italian architect Aldo Rossi writes in his Scientific Autobiography, architecture can be understood as a stage upon which human life unfolds—a setting for the rituals of inhabiting, where life itself takes place. What we inhabit is not an infinite, abstract, or geometric space, but rather a contingent, shifting, and imprecise place—one inseparably tied to the body that brings it into being. We may assume the stage—delimited by material boundaries—to be more enduring than the events it hosts, just as places often outlast those who pass through them. And yet, certain gestures and occurrences resonate beyond a single lifetime, echoing across generations and geographies. Perhaps that is why, in the midst of a hurried routine, someone pauses to make the sign of the cross when passing a church, or why stadium-goers chant the same verses every Sunday—words that have crossed oceans and decades without ever losing their force.

Rhythm is the foundation of the time we inhabit. Architecture is a trace, a mark, a gesture that both presents and re-presents the shifting intensities of rhythm as they unfold through our actions and environments. This rhythmic imprint offers an escape from abstract, scientific notions of space and time, anchoring us instead in the lived experience of a body in motion—a body that, as Perec writes, "moves from one space to another, doing its best not to bump into things" (2001, 25). To relate architecture to the body through rhythm is, perhaps, to recover all that architecture might become—beyond its mandates of function and efficiency. But doing so, requires careful attention to that elusive resonance that pulses between permanence and ephemerality—each time a place is inhabited with meaning.

1 All citations in this article have been translated from Spanish to English by the article's translator except for Zumthor's quotes (2006).

2 Located in the northeastern part of the city, Aranjuez is home to over 163,000 residents and spans an area of 4.88 square kilometers. Urbanization began in the early 19th century through spontaneous settlement, and this, together with the area's topographical conditions, contributed to the initial absence of public space in its urban layout (Medellín City Hall 2019).

3 Edgar Mazo Zapata is an architect who graduated in 2003 from the Faculty of Architecture at the Universidad Nacional de Colombia. He is a lecturer and co-director, alongside Sebastián Mejía, of Connatural, a landscape architecture studio.

4 Reference to the exhibition titled "In the Troubled Air…," curated by Georges Didi-Huberman for the Museo Reina Sofía in Madrid (Spain), which alludes to a verse from Romancero gitano, written by Spanish poet Federico García Lorca.