How to Cite: Guzmanruiz, Edgar. "Spatial Dialogues: A Performative Installation of Architecture, the Body, and Everyday Life in Public Space". Dearq no. 42 (2025): 54-65. DOI: https://doi.org/10.18389/dearq42.2025.06

How to Cite: Guzmanruiz, Edgar. "Spatial Dialogues: A Performative Installation of Architecture, the Body, and Everyday Life in Public Space". Dearq no. 42 (2025): 54-65. DOI: https://doi.org/10.18389/dearq42.2025.06

Edgar Guzmanruiz

Universidad de los Andes, Colombia

Received: November 5, 2024 | Accepted: March 13, 2025

We shape our buildings; thereafter they shape us

Winston Churchill, Grammar of Complexity

This article presents reflections and findings on the work processes involved in the performative installation Diálogos espaciales, situated in public space. It explores and reveals aspects of the reciprocal influence between architecture and the human body, shedding light on the connections between space, emotion, and behavior through activations. According to the results, these connections—which depend on empathy between performers and the audience, activated through emotional and procedural memory—ultimately engage episodic memory. The research-creation methodology in art combines the analysis of theoretical references, the study of similar creative works, and performative experimentation based on the notation of transcultural human actions.

Keywords: Art and architecture, public space art, installation, performance, space, body, behavior, emotion, memory.

As a sculptor, I have always found the performative character of sculpture to be powerful. First, because of the "gymnastics" required to construct a volumetric piece; then, because of the movement involved in packing and transporting it to the exhibition site. Finally, because of the viewer's own movement—circling around, stepping back, and approaching the work in order to fully appreciate it. These performative qualities are heightened in installations, whose immersive nature compels viewers to move through them.

I have created fifteen installations since 1998. Most, are site-specific, and placed in various exhibition spaces. After exploring these works, many visitors—including musicians, performers, and models—have often expressed interest in using them as a "creative backdrop" for concerts, performances, or photo sessions. Building on this experience, I designed Diálogos espaciales as my first installation explicitly intended to be activated by performers, allowing it to fully unfold its formal potential.

All the whole world's a stage, and all the men and women merely players; they have their exits and their entrances; And one man in his time plays many parts.

William Shakespeare, As You Like It

From birth to death, architecture acts as an invisible director—guiding, interrupting, and enabling the actions of our bodies. In doing so, it establishes a daily corporeal script that shapes our behavior and emotions. This interaction is dynamic, ever-evolving throughout our lives. Many of our movements are choreographed by the built environment. In this sense, architects and builders are, to a great extent, the choreographers of our everyday gestures. On the temporal stage of existence, the repetition of human actions emerges as a timeless choreography—one that transcends cultural boundaries and connects the individual with the collective.

Diálogos espaciales is a performative installation that explores the reciprocal interactions between space, corporeality, behavior, and emotion. Movement transforms and animates the built environment through a series of activations that expose these connections, offering a space to examine their influence on both perception and inner experience (fig.1).

Figure 1_ Activation of Pabellón ARQDIS 2023. Source: the author.

To pursue this objective, I developed a conceptual framework by analyzing theoretical references and examining the work of artists, choreographers, performers, and architects. I compiled a list of space-events linked to actions, shaped the installation, and integrated devices and objects into the piece. I also worked with the artists to develop notation mechanisms, define relationships with the public space where the work is activated, and, together with the performers, review and analyze the documentation of the activations.

One of the key references in my work is Wolfgang Meisenheimer (2007), whose approach helps me interpret and categorize different environments or atmospheres—what I refer to as space-events. These follow patterns of human actions and behaviors linked to their surroundings and, as transcultural, are widely recognizable.

Colin Ellard (2016) helps me grasp how the environment shapes human behavior and decision-making, particularly our perception of safety and control.

An article by Henk Borgdorff (2017) offers valuable insights into essential aspects of research grounded in artistic practice.

Richard Schechner (2003) points out that much of human behavior is not spontaneous, but rather follows preexisting patterns that we learn, internalize, and enact in different situations—a concept he refers to as restored behavior. His research is key to understanding the relationship between identity and performance, as it reveals how our identity, being tied to behavior, is flexible and adapts according to context and audience. He defines performance as a repeatable and transformable practice within a performance spectrum that ranges from spontaneous acts to highly structured events. In the activations of the installation, rehearsed and improvised movements coexist.

The installation-performances of Chinese artist Ya-Wen Fu (2024), which integrate space, the body, and the sound produced by the work, are valuable in that they reveal how the sculptural objects created by the artist enhance action.

The interventions of Franz Erhard Walther (Sariego 2018) and the acrobatic choreography in space by Yoann Bourgeois (2024) demonstrate how minimalism enhances the impact on the viewer.

The actions of Angie Hiesl and Roland Kaiser (2024), along with that of Austrian choreographer Willie Dorner (2024), offers valuable insights into working with young performers through non-narrative approaches, characterized by a thoughtful selection of costumes and a strong focus on observation and documentation.

The works of the company DIAVOLO: Architecture in Motion (Heim 2024) and of Alex Schweder and Ward Shelley (2016) demonstrate the power of bodily movement to transform architectural space in front of an expectant audience.

The architectural installations in public space by John Hejduk (2024) and by the collective of artists and architects Haus-Rucker-Co. (2024), with contributions from Laurids Ortner—who was my professor at the Academy of Arts in Düsseldorf, Germany—have taught me various ways of creating presence through this type of work.

The work of landscape architect Lawrence Halprin and choreographer Anna Halprin (2007) on the intersection of architectural space and human movement offers meaningful insight into collaborative methodologies between performers and architects. Their interdisciplinary workshops and the scores or open-instruction diagrams, which serve as action notations, guide the interaction between bodies and built environments. The movement exercises are used to test and adjust architectural designs before construction.

Peter Handke's poem Song of Childhood (1986) poetically inspires the creation of actions that evoke bodily movements from childhood.

The installation stands in contrast to the first organic, sheltered space we inhabit—the maternal womb. At birth, we enter a world shaped largely by perpendicular geometries that define the spaces we move through and occupy throughout life. In response, the piece adopts orthogonal forms. With the strength of simplicity, a 3.2-meter metal cube houses 24 wooden blocks, which can either be stacked inside or arranged outside (fig. 2).

Figure 2_General installation layout. Source: the author.

The wooden blocks are divided into three types: nine single blocks (50 cm × 50 cm × 40 cm high), four of which have a side door that conceals a mirror, and fifteen double blocks (100 cm × 50 cm × 40 cm high) (fig. 3). Through their movement, the performers can build, shape, and transform various spaces and pieces of furniture.

Figure 3_ Detail. Source: Juan Carlos Alonso.

The cubic structure functions as a tabula rasa for creation, offering hundreds of possibilities. It becomes a workspace with a regular 6 × 6 grid, into which the blocks fit modularly, like pieces of a giant LEGO set. The resulting configurations—floors, walls, windows, doors, openings, tables, chairs, stairs, pedestals, among others—are easily recognizable to the audience (fig. 4).

Figure 4_ Activation of Pabellón ARQDIS 2023. Source: the author.

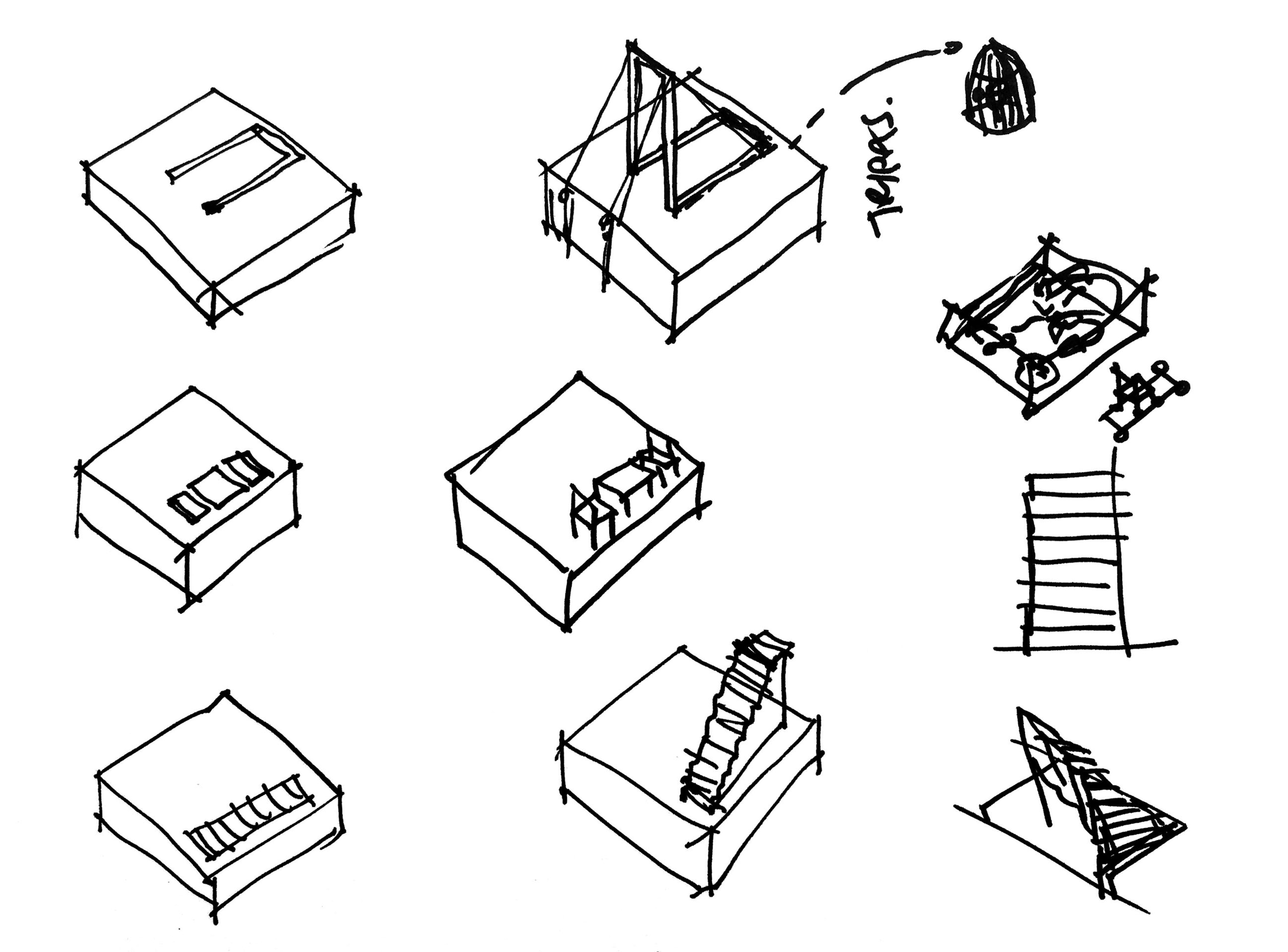

The formal intentions begin to take shape through a scale model, a series of sketches, rendered virtual models (figs. 5 and 6), and architectural plans. In parallel, construction details are refined, and various spatial arrangements—both within and beyond the structure—are tested and evaluated.

Figure 5_ Sketch. Source: the author.

Figure 6_ Territorial Space-Event. Source: the author.

The movement of the blocks is made easier by three or four openings per section, similar to those of a bowling ball, allowing for a better grip from above. Each shorter side also includes two lateral slots, enabling transport by two people. The color blue that was chosen creates a strong contrast with the typical tones of public space, evoking private environments that are rarely encountered outdoors. To ensure uniformity and precision in the fit, the block panels are cut using a CNC router (fig. 7).

Figure 7_ CNC Router Cut Section. Source: the author.

Various types of additional objects enhance the performers' actions:

Figure 8_ Activation at Galería Santa Fe. Source: the author.

Meisenheimer's (2007) spatial classification produces an Excel chart with 18 space-events that convey specific concepts. Each is linked to movements and gestures of approximate duration, objects, costumes and makeup, reference images, bibliography, and relevant links. From these 18, we chose to work with the following space-events:

The first action reenacts birth: the female performer "gives birth" to the male performer. The movements evoke the emergence from the first inhabited space—the womb. The body expands, turns, confronts the light, the world, and the need for protection.

Following the birth, the performers explore movements from early childhood and mutual support. They crawl, climb, and run, playing with balance and allowing their bodies to move spontaneously and freely.

A drone guides the spatial exploration, synchronizing its movement with the performers in a coordinated dance.

In continuity with the previous action, these movements focus on marking boundaries, dividing space, and exploring the edges of the surrounding architecture. During the activations, the performers build block walls to enclose and later "liberate" the other. They also expand the limits of the installation by scattering the boxes. At times, they block the public's path to provoke reactions and observe their interaction.

In the session with the drone, it becomes a strange and threatening object from which the performers must protect themselves (fig. 9). In other instances, the artists position themselves at the periphery of the public space to convey a sense of control and surveillance. Ellard (2016) suggests that this behavior has evolutionary and psychological roots, as our ancestors avoided open areas and preferred edges or elevated positions to enhance their view of the surroundings and anticipate potential threats.

The positioned "doorframe" serves as a threshold—a space of transition and potential, where hesitation, anticipation, and the crossing of past and future, public and private, profane and sacred, converge. This element marks beginnings, endings, and rites of passage (fig. 10).

Slings, harnesses, ropes, Velcro, and blocks visually define space through relational dynamics: meeting, sharing, parting, returning, negotiating, dancing, or coexisting around the table or hearth. At times, interaction with the audience expands when external participants venture to assist in moving boxes from one side to the other (fig. 11).

Both the mirrors, which unfold from certain blocks, and the "doorframe" are used to produce a mirrored reflection. Through them, the performers' movements are doubled, thereby intensifying the sense of empathy (fig. 12).

The ascending and descending sagittal space is explored on several occasions, as some performers move to the top of the structure and connect—visually and physically (also through slings)—with those remaining below. The movements oscillate between elevation and descent, associating ascent with triumph and hope, but also with danger; and descent with defeat, weight, and darkness (fig. 13).

The performer arranges the blocks to configure the horizontal space of a bed, a symbol of refuge, calm, and protection. Suspended by slings just above his body, the female performer then mirrors actions that represent her partner's dreams, as he lies in introspection (fig. 14).

The arrangement of the blocks, based on the negative space occupied by a bed, marks the final threshold of life. A symbolic leap occurs—from the organic space of the womb to the orthogonality of the grave and the cemetery (fig. 15).

Figure 9_ Activation with Drone. Source: the author.

Figures 10 to 12_ Activation of Volver a los Andes. Source: the author.

Figure 13_ Activation of Pabellón ARQDIS 2023. Source: the author.

Figure 14_ Activation of Volver a los Andes. Source: the author.

Figure 15_ Death Space-Event. Source: the author.

If musical notation is a writing system that graphically represents a musical piece, how can performance or choreography be notated?

Our notation emerges from working with a 1:10 scale model that includes movable figures representing the participants. In sessions prior to the activations, we explore the model based on the actions defined by the space-events (fig. 16). To trigger the sequence and dynamics of the performers' actions, I provide them with a list of terms associated with each space. These words, which serve as creative prompts, allow the performers to interpret and create within the given guidelines.

Figure 16_ Work session with the model. Photographer: Sebastián López. Image Rights: Office of Communications and Cultural Management, School of Arts and Humanities, Universidad de los Andes.

They select and arrange the blocks for each activation, and with my feedback, we agree on movements that we rehearse repeatedly. They know the blocks are heavy and sturdy, designed to withstand their bodies and abrupt motions. Moving and stacking them requires effort and planning, which means that transitions between space-events take time.

We record the notation through photos, videos, and drawings to consult in each session. In this way, we collectively "weave" the choreographic thread.

When inactive, the piece functions as a public sculpture. Each morning, the blocks take on different forms: sometimes evoking nearby buildings or pieces of urban furniture; other times forming enclosed walls or staircases (fig. 17). Later, the activations unfold the work into the public space, which is "claimed" by the performers.

Figure 17_ Placement in public space. Source: thr author.

Because the work explores transcultural space-events, the installation is set in a public space to engage the broadest possible audience. In the plazoleta at Galería Santa Fe, this diversity becomes tangible in the mix of La Concordia residents, tourists, people experiencing homelessness, students, and schoolchildren who pass through and interact with the space. By "externalizing" actions typically confined to interior spaces, the performances invite those who witness them to reflect and imprint these experiences into their own memory. The ten activations, staged across three different sites—two public and one semi-public—last between one and four hours each and are preceded by multiple rehearsals.

The performers, aged between 25 and 35 and from backgrounds in dance and theater, are drawn to the project for its potential to explore the relationship between body and architecture. All activations and rehearsals are documented through photographs and video for later analysis with the performers. Audience reactions are also observed and shared. After the activations—and occasionally during them—we engage in conversations with spectators about their perceptions of the work. These interactions are informal yet intentional, avoiding the interview format, which could feel invasive.

Peruvian performer Renzo Rospigliosi states that the installation's activations repeatedly place him in situations of imbalance, as movements involving harnesses and blocks generate bodily instability and discomfort. He considers that a valuable application in architecture would be to introduce spatial imbalances—without endangering people—in order to activate rarely explored sensations and stimulate creativity in design. This idea connects with the work of the Halprins (2007), who integrated dance and architecture in their spatial approach.

As part of the project to activate the plazoleta at Galería Santa Fe, the Impromptvs collective conducts three performance workshops with members of the La Concordia community and external participants. The outcomes of these sessions are incorporated into the performative actions through recorded voices, workshop soundscapes, and invitations to participate.

One activation emerges from feelings expressed about living in Bogotá, while another is shaped by the strong participation of the workshop attendees. The collective believes that these activations act as catalysts for relationships and encounters, expanding the boundaries between art, space, and community.

The actions within the installation generate a constant negotiation between the body, the materiality of space, and the presence of the other. They shift between containment and expansion, stability and reconfiguration, transforming the space into a mutable organism that responds to interaction. To build, deconstruct, assemble, and collectively displace activates a dynamic between playful exploration and the symbolic reconfiguration of territory.

Together with the collective, we observe that the audience fluctuates between distant observation—marked by curiosity—and an occasional desire for appropriation. The ability to intervene in the space using the blocks encourages exploration, surprise, and spontaneous dialogue.

Several attendees noted that the objects encouraged them to create choreographies of encounter, while others felt the installation invited them to move beyond the passivity of traditional artistic experiences. In addition, some participants from the performance workshops became actively involved in the process (fig. 18).

Figure 18_ Activation at Galería Santa Fe. Source: the author.

Diálogos espaciales exists as an object that condenses creative processes and envisions future actions across different settings. Ideally, access to a rehearsal space two weeks prior to the activations would allow for a more refined staging. New sculptural objects, as well as sound and lighting explorations, could further expand the research-creation process and open up new dimensions of the work.

The activated installation is not a finished outcome, but a minimalist platform for exploration that, with each activation, marks the beginning of new processes. It arises from the interaction and expansion of artistic genres such as installation and performance, where architecture and its relationship with the body serve as the working ground.

Following Borgdorff (2017), the installation operates as "embodied knowledge in process," where experimentation, intuition, and perception are essential. Furthermore, artistic research adopts non-linear and exploratory methods that call for dissemination.

A significant aspect of the work becomes apparent through conversations with attendees and observation of their bodily reactions: the audience's emotional connection to the performers' experience through empathy (fig. 19). Certain actions likely activate the mirror neuron effect and emotional memory, generating identification with "the other." This connection becomes more pronounced during moments of intense physical and mental demand for the performers, such as the use of harnesses, situations of imbalance or height, expressions of fear or threat, the need for assistance, and gestures of care and affection. These circumstances resonate with the audience, prompting a recognition of the experience within themselves. Schechner (2003), for instance, examines how actors access emotional memories to deepen their performance and how audiences respond emotionally to what they witness.

Figure 19_ Activation of Volver a los Andes. Source: the author.

Procedural memory influences behavior when the actions of performers and audience members are not entirely spontaneous but, as Schechner (2003) suggests, follow preexisting patterns that are learned, internalized, and repeated. This is evident in the performers' iterative movements—whether in the acquisition of motor skills, the use of gestures drawn from dance, theater, and circus acts, or the evocation of pictorial or aesthetic references—as well as in the enactment of everyday rituals: going to bed, walking down a runway, or looking in a mirror.

Repetition also appears in the expressions of participants in the workshops organized by Impromptvs, particularly in how they describe the experience of inhabiting Bogotá. Adult spectators, on the other hand, tend to remain on the periphery, instinctively respecting the spatial boundaries set by the artists using the blocks. This behavior suggests a learned response to architecture as an unquestionable spatial imposition.

Episodic memory serves as a bridge between emotional and procedural memory, enabling us to recall similar experiences and strengthen our empathetic connection to what we observe. The exploration of Diálogos espaciales as a research-creation platform—where installation and performance converge—opens new paths for transdisciplinary inquiry. Anchored in architecture and its reciprocal influence on body and mind, the work integrates the three forms of memory present in daily life: emotional memory, which provides expressive depth; procedural memory, which enables the technical repetition of movements and actions; and episodic memory, which connects both audience and performers with individual and collective experiences.

Although architecture is typically conceived to endure, this performative installation reveals—much like a time-lapse—how the built environment is transformed by our actions and, in turn, profoundly and intimately shapes us. Architecture and choreography share a fundamental connection: both shape our experience of space and time through movement (fig. 20).

Figure 20_ Activation of Pabellón ARQDIS 2023. Source: the author.

Created and directed by: Edgar Guzmanruiz.

Performer 1: Claudia Angélica Gamba (Pabellón ARQDIS 2023)..

Performer 2: Renzo Rospligiosi (Pabellón ARQDIS 2023).

Performer 3: Ana María Perdomo of the Impromptvs collective (Activation at Galería Santa Fe and Volver a los Andes).

Performer 4: Daniel Alejandro Corredor of the Impromptvs collective (Activation at Galería Santa Fe and Volver a los Andes).

Performer 5: Sebastián Arenales of the Impromptvs collective (Activation at Galería Santa Fe).

Performer 6: David Arenales of the Impromptvs collective (Activation at Galería Santa Fe).

Audiovisual Production: Luis David Cáceres (Pabellón ARQDIS 2023).

Performance Co-Direction: Luis David Cáceres (Pabellón ARQDIS 2023).

Costume Design: Rebeca Rocha.

Drone Operator: Alejandro Ramírez Villaneda (Pabellón ARQDIS 2023).

Documentation and Outreach: Johan Sebastián López, Alexander Rodríguez, Luis Antonio Silva, Communications Office, School of Arts and Humanities, Universidad de los Andes, Edgar Guzmanruiz, Luis David Cáceres, Juan Carlos Alonso, Impromptvs collective.

Metal Structure Design and Direction: José Roberto Bermúdez Urdaneta.

Metal Structure Construction: William Garcés Rosales, Eury Emilson Quintana.

Assembly and Disassembly: William Garcés Rosales, Eury Emilson Quintana.

Wood Carpentry: José Kabalén Amar.

CNC Machining: Oscar Parada, School of Architecture and Design, Universidad de los Andes.

Project Management and Administration: Ana Malaver, Alejandro Giraldo, Sair Nolasco - Research and Creation Center, School of Arts and Humanities, Universidad de los Andes.

Sponsorship: Office of the Vice President for Research and Creation — Research and Creation Center, School of Arts and Humanities, and School of Architecture and Design, Universidad de los Andes, Space Activation Grant, Galería Santa Fe 2024, Plazoleta category, IDARTES.

Location 1: Plazoleta in front of the Japan Center and Block E or CAI, Calle 18 # 0-34, Universidad de los Andes1.

Monday, October 9, 2023: 2:00 p.m.

Tuesday, October 10, 2023: 6:30 p.m.

Wednesday, October 11, 2023: 1:00 p.m.

Thursday, October 12, 2023: 10:30 a.m.

Friday, October 13, 2023: 3:00 p.m.

Saturday, October 14, 2023: 12:00 m.

Location 2: Plazoleta of the Santa Fe Gallery2, located on Carrera 1A between Calles 12C and 12D, in the neighborhood of La Concordia.

Friday, October 18, 2024: 1:00 p.m.

Friday, November 1, 2024: 1:00 p.m.

Friday, November 15, 2024: 1:00 p.m.

Lugar 3: Plazoleta Richard, Calle 18 # 0-34, Universidad de los Andes3.

Saturday, November 30, 2024: 12:00 m.

* This work is the result of a third year of research-creation, funded by the Assistant Professors Support Fund (FAPA) of the Center for Research and Creation (CIC) at the School of Arts and Humanities, Universidad de los Andes. It was selected as part of the Pabellón ARQDIS 2023 event. It received the 2024 Public Space Activation Grant from the Galería Santa Fe Stimulus Program, in collaboration with the Impromptvs collective. Activation was also featured in the 2024 Volver a los Andes event. The original title in Spanish is Diálogos espaciales: una instalación performática de arquitectura, cuerpo y cotidianidad en el espacio público. When referring to the project throughout the text, I have used the title in Spanish, rather than the English translation.

1 https://pabellon.uniandes.edu.co/.

2 https://galeriasantafe.gov.co/proyectos-ganadores-de-la-beca-red-galeria-santa-fe-2024/.

3 https://arte.uniandes.edu.co/noticia/dialogos-espaciales/.