How to Cite: de Molina, Santiago. "Body, Space, and Intimacy: A Genealogy of Booths and Cabinets in Art and Architecture". Dearq 44 (2026): 20-29. https://doi.org/10.18389/dearq44.2026.03

How to Cite: de Molina, Santiago. "Body, Space, and Intimacy: A Genealogy of Booths and Cabinets in Art and Architecture". Dearq 44 (2026): 20-29. https://doi.org/10.18389/dearq44.2026.03

Santiago de Molina

San Pablo CEU University, Spain

Received: November 25, 2024 | Accepted: June 11, 2025

Spaces designed for a single individual have historically embodied introspection, privacy, and inner dialogue. This article examines how such spaces have gradually lost relevance within contemporary architecture, even as they have been the subject of deeper inquiry in the field of art. The abrupt disappearance of telephone booths, for example, cannot be explained solely by the rise of mobile telephony; with their decline, a genealogy of spaces etymologically linked to the notion of the booth as an individual refuge also fades. The analysis presented in this article considers how the configuration of such proximate environments continues to shape the individual's sensory experience and thus retains significance today, positioning proxemics as one of the most productive and meaningful areas for contemporary architectural development.

Keywords: Individual spaces, cabinets, booths, body, intimacy, contemporary art, bodily perception.

From hermits' caves to telephone booths, the history of humankind has been marked by the search for spaces of solitude and introspection. The need for such refuges, closely tied to the body, has not disappeared, yet their striking reduction in number is undeniable.

In the 1950s, nearly 250,000 telephone booths were in operation in the United States. By the 1960s, New York alone had around 60,000. From the 1970s until the end of the century, the nationwide figure exceeded 2 million. With the advent of the twenty-first century and the rapid spread of mobile telephony, however, booths began to vanish. Today, it is estimated that only about 5,000 remain—a negligible figure on a global scale.1 The situation in the United Kingdom followed a similar trajectory. In the 1950s, 49,531 telephone booths were recorded, and their number continued to rise, peaking in the 1990s at around 100,000. Despite having become a consolidated symbol of national identity, the turn of the century brought a drastic decline: by 2010, only about 51,500 remained. Today, the number is estimated at roughly 21,000, many repurposed for functions quite different from their original use.2 These data reveal a similar pattern worldwide.

This reduction has generally been attributed to the emergence of new technologies, yet it is often overlooked that the secondary uses of these spaces—ranging from providing shelter for clearer communication to serving purely symbolic functions—also disappeared along with them. From the perspective of spatial analysis, this terrain has been largely abandoned and remains insufficiently studied. The extinction of the telephone booth, however, makes it possible to systematically trace the qualities of a space intimately connected to both the bodily and psychological dimensions of human experience. With its disappearance, a place also vanishes in which the body sustained a distinctive tension between intimacy and isolation from society.

This need for individual spaces, intrinsic to human corporeality (Le Breton 1990, 45), persists despite the transformations in the forms that accommodate it. It is therefore worth considering the domains in which it has managed to transmute. At this state, an initial hypothesis may be proposed: the tension between spaces designed for a single body and the outside world has found a sublimated form of expression in certain artistic interventions, where its persistence remains tangible. From this vantage point, it may even be possible to recover what the booth contributes to architecture as a specific territory for an individual fully aware of their own bodily condition.

Rather than adopting an interpretative critique with didactic aims—intended to make the contents and features of cabinets and booths explicit—or a merely descriptive approach that translates into words what the trained eye can already perceive, the approach proposed here seeks to develop a formalist critique. Such a critique is intrinsic to the discipline of architecture, insofar as it aims to identify the internal coherence of a "lost" typology and, in a certain sense, to reconstruct its genealogy.

The methodology proposed to test this hypothesis consists of delimiting the analysis through an examination of the etymology of the term booth, with the aim of tracing its history both as a space and as a form. This is followed by a comparative study of several significant cases in the field of art, undertaken to shed light on the contexts in which such spaces persist—contexts where intimate bodily distance, understood in its dimensional sense, remains particularly relevant today.

The goal is to develop concepts that clarify phenomena within the field of architecture and that may serve as a framework for proposing positions or conceiving new interventions. In doing so, the intention is to enrich the vocabulary of a discipline that currently struggles to articulate itself around one of its key dimensions: the phenomenological and proxemic aspects of immediate bodily distance.

Philosophy, anthropology, history, and architecture have long devoted attention to the study of small spaces designed for individual use. The retreats of anchorites and the cabins of writers and philosophers—from Henry David Thoreau's refuge at Walden Pond to George Bernard Shaw's cabin in Hertfordshire, and Martin Heidegger's hut in Todtnauberg—illustrate a type of personal refuge where concentration, isolation, and intellectual life are inextricably intertwined (Olmedo and Ruiz de Samaniego, 2011).

However, upon closer examination, not all of these spaces respond to the same needs. The hermit's refuge, conceived for prayer and seclusion, differs from the writer's cabin, designed for intellectual creation. A notable example is George Bernard Shaw's rotating cabin, built to maximize sunlight (Duque 2011, 35). It is no coincidence that the cabin—as a space for creation—was never originally associated with booths, cabinets, or the Renaissance and Baroque studiolo. Cabins have consistently embodied a longing for "solitude, altitude, silence, essentiality," together with asceticism and an unquenchable hermitic vocation—qualities that a mere telephone booth does not share (Ruiz de Samaniego 2011, 10).

It is precisely the etymological trajectory of the term booth that allows us to grasp the nuances of these spaces in relation to the body and psyche of their occupants. Returning to its strict etymological sense, the word clarifies its essential difference from the broader category of voluntary exile spaces. With roots in Old French, booth derives from cabinet and its diminutive cabine, which in turn gave rise to both cabinet and booth (Calzada Echevarría 2003, 355). By the mid-fifteenth century, the cabine—essentially a room as small or private as a telephone booth—was already understood as a place of individual retreat for thinking, reading, or simply being alone, much like the studiolo of the Italian Renaissance.

Similarly, the cabinet emerged as a secluded space where kings and nobles could study, rest, or receive close advisers and friends, in such proximity that the body and mind themselves became both landscape and object of reflection. From this heightened awareness of the immediate, poet W. H. Auden wrote, "About thirty inches from my nose is the border of my person, and all the untouched air in between is my private ancestral demesne" (Auden 1966, 139). In a room scarcely admitting more company than oneself, within the emerging condition of individuality, the heads of noble houses and Renaissance palaces could relate to their objects and thoughts at a distance that proxemics would later define as "intimate" and "personal" (Hall 1966, 143).3

Shortly thereafter, in his seventeenth-century treatise, Benit Bails defined cabinets as "secret rooms where the master of the house withdraws to write or study, from which it follows that they need not be very large" (Bails 1983, 84), emphasizing not only their modest dimensions but also the concealment they afforded their inhabitants.

Since then, the functional purpose of the cabinet has remained tied to the intimate knowledge of certain objects, serving as a means of understanding the world beyond. Paintings created specifically for these rooms—intended to be viewed at very close range—gave rise to a distinct pictorial genre known as cabinet painting (Chilvers 1992, 375). In such spaces, the gaze and the sense of touch interact: the eye travels across the detailed surfaces of the paintings with the pleasure of one who might hold the work in their hands and place their iris just centimeters from the canvas.

Cabinets, in addition to being small hidden rooms, also existed as pieces of furniture—somewhere between a desk and a portable chest—used for storing private documents. Their marquetry decoration, the hidden drawers designed to safeguard correspondence from prying eyes, and the protection provided by locks and compartments all belonged to the same realm of privacy as the cabinet-room itself (Feirer 1988). Interestingly, the semantic transfer from furniture to the space that contains it, and vice versa, is a recurrent phenomenon in the history of architecture, revealing the blurred boundaries between disciplines.

The cabinet maintained its supremacy as an intimate space among social classes that possessed objects to safeguard—sensitive correspondence and valuables—and who considered their own solitude as worthy of preservation alongside those possessions. Soon thereafter, and almost inevitably, the cabinet evolved into a spatial typology for collecting singular objects, emerging as a direct consequence of this genealogy of spaces designed for storage. At a time when travel, rarities, and the possession of mirabilia demanded a dedicated place, the space-furniture housing such collections came to be known as the cabinet of curiosities.

Following this evolutionary path, cabinets of curiosities—with their disorderly diversity of treasures—eventually gave rise to the modern museum and, a few centuries later, to the systematic development of natural philosophy and modern science (Pevsner 1979). It is no coincidence that the origins of the Royal Society are linked to the acquisition of Robert Hubert's cabinet of natural rarities; that the Royal Cabinet of Natural History in Madrid was transformed into the Royal Museum of Natural Sciences in 1818; or that the extraordinary collection of naturalia, artificialia, mirabilia, scientifica, and library of the Jesuit Athanasius Kircher's cabinet of curiosities anticipates the birth of the Enlightenment encyclopedia.

Figure 1_ The Soane Family Tomb. Source: Courtesy of the Soane Museum.

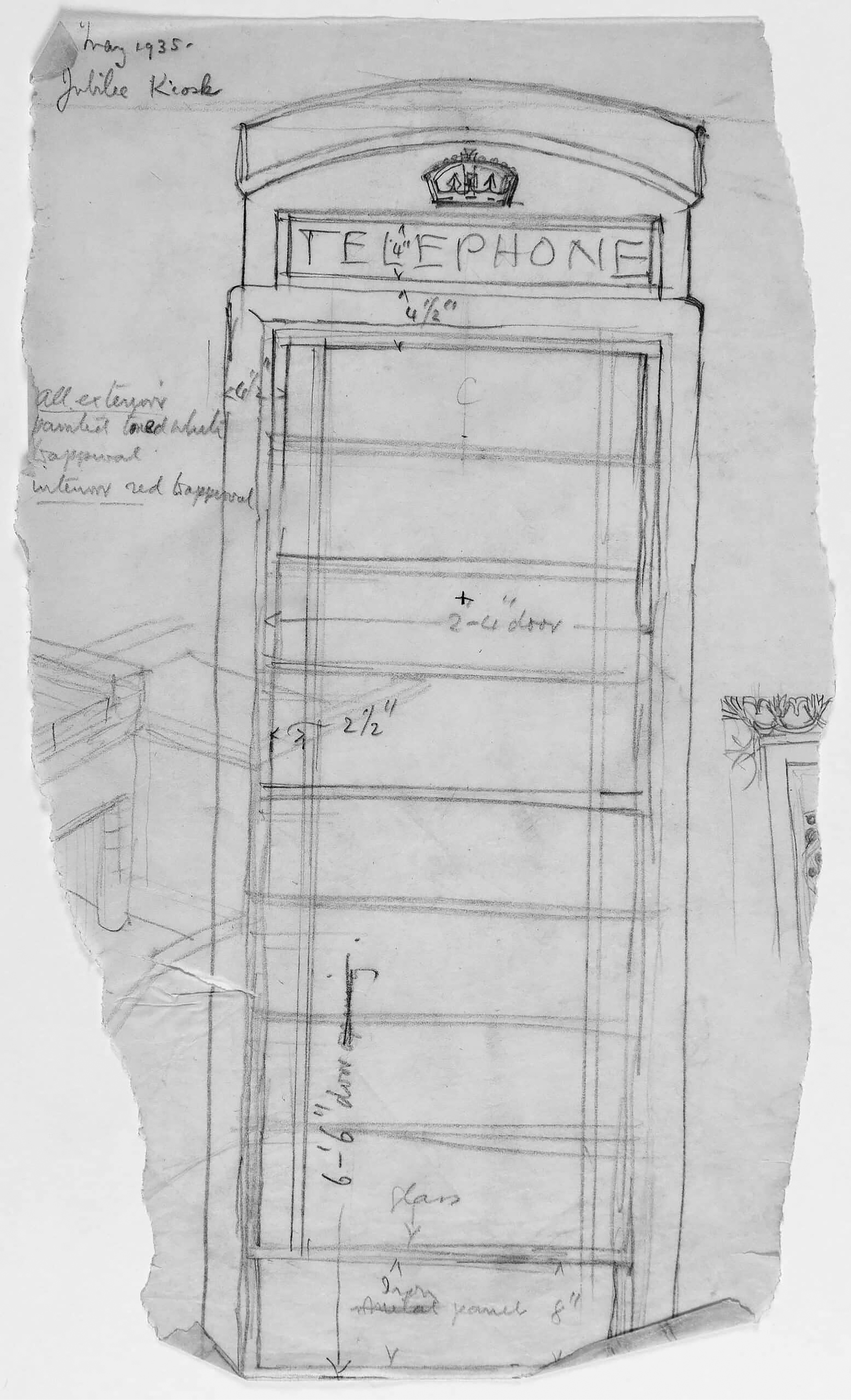

In another direction, the booth became associated with the telephone once it became necessary to provide a place where one could communicate at a distance with adequate privacy. Telephone booths achieved their most characteristic form through the design of Sir Giles Gilbert Scott. Drawing inspiration from Sir John Soane's monument for his wife's tomb (fig. 1)—a small lowered dome with four Ionic columns at its corners—Sir Giles Gilbert Scott transformed this funerary element into an enclosed space where a person could isolate themselves from the surrounding noise of the city to speak at a distance. To enhance visibility, the booths were later painted red and deployed rhythmically across the English landscape in various versions (fig. 2). As we have seen, today, despite their popularity and the attempts to repurpose them as charging points for mobile phones or as Wi-Fi hotspots, the passage of time has not been kind. With the disappearance of telephone booths, we witness the end of a genealogical line of spaces designed to shelter a single individual within the sphere of the immediate (Bermejo 1987). Yet Christopher Alexander's insight regarding the necessity of solitude remains valid: "No one can be close to others without also having the opportunity to be frequently alone" (Alexander 1977, 669).

Figure 2_ Giles Gilbert Scott, Jubilee Kiosk (1935). Pencil on tracing paper, 317 x 190 mm. DMC 3198.1. Source: Courtesy of the Drawing Matter Collection.

The resurgence of spaces of individuality associated with the genealogy of booths can be traced at the turn of the twenty-first century. While telephone booths served as catalysts for numerous artistic interventions, those most closely tied to the relationship between an individual and voluntary solitude were not exclusively based on the form devised by Sir Giles Gilbert Scott.4 Works such as David Mach's Out of Order (1989) (fig. 3) or, more recently, Banksy's Phone Booth (2006) have redefined the booth primarily from an urban art perspective. Some artistic interventions have treated the booth as a ready-made, re-signifying its original form, while others have explored the relationship between body and space at an intimate distance, delving into its conceptual meaning. Without addressing the impact of new technologies on intimacy and its redefinition through the booth—a subject extensively studied from philosophical, sociological, anthropological, political, and psychological perspectives (Ríos-Coello and Matesanz 2021)—it is nonetheless worthwhile to pause and compare the redefinition of the cabinet and the booth as witness spaces, from a purely memorial and proxemic standpoint.

Figure 3_ David Mach, Out of Order (1989). In Kingston, by the Thames. Source: Wikipedia.

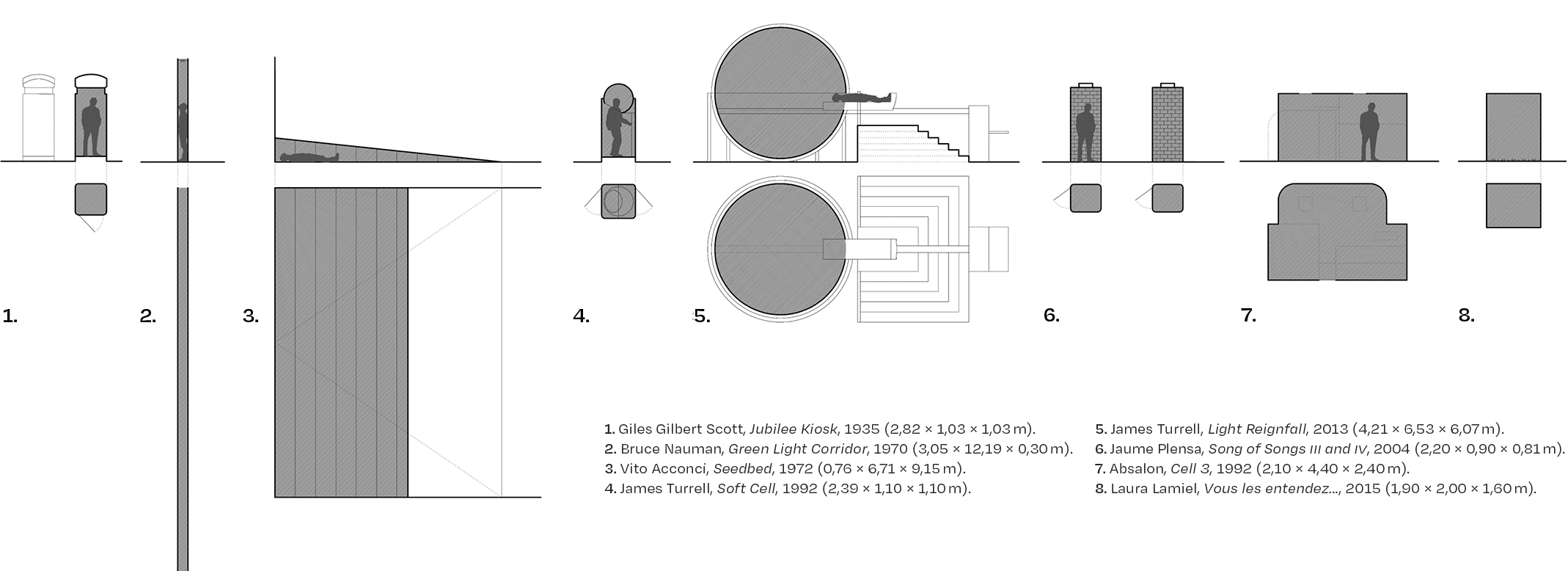

The exploration of individual space as a site for reflection on corporeality has gained increasing presence throughout the twenty-first century. When comparing experiences from the last quarter of the twentieth century with those of the first quarter of the twenty-first, it becomes clear that spaces and interventions linked to individual exploration through the lens of the cabinet have acquired growing relevance. Works such as Bruce Nauman's Green Light Corridor (1970) (3.05 × 12.19 × 0.30 m) and Vito Acconci's Seedbed (1972) (0.76 × 6.71 × 9.15 m), rooted in minimalism and body art, set important precedents for the investigation of individual space and corporeality. Similarly, the experiments of Dan Graham and James Turrell, and works like Call Waiting (1987) and Soft Cell (1992) (2.39 × 1.10 × 1.10 m) (fig. 4), or more recently Light Reignfall (2013) (4.21 × 6.53 × 6.07 m), constitute an intermediate field in which transparency and overexposure, on the one hand, and the manipulation of vision and light perception, on the other, have opened distinct lines of work where booths form an essential apparatus. This also applies to Jaume Plensa's booths, such as those in the Song of Songs III and IV series (2004) (2.20 × 0.90 × 0.81 m), where a deliberate colored coldness contradicts the presence of the body and the booth's function as a shelter for thought. However, it is above all at the beginning of the twenty-first century that numerous artistic initiatives have emerged capable of resonating with the spatial logic of the historical cabinet.

Figure 4_ Comparative chart of different booths at the same scale. Source: the author.

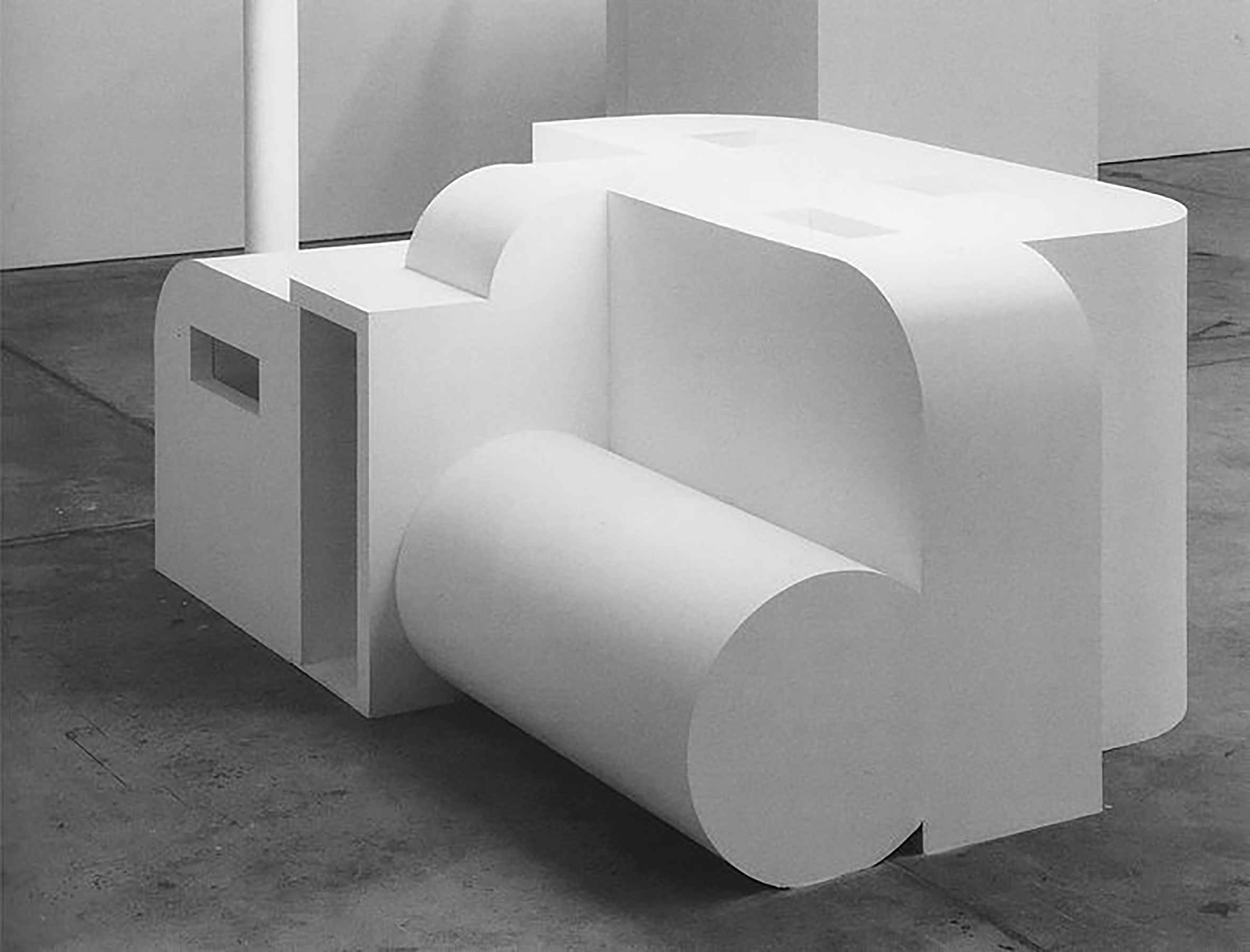

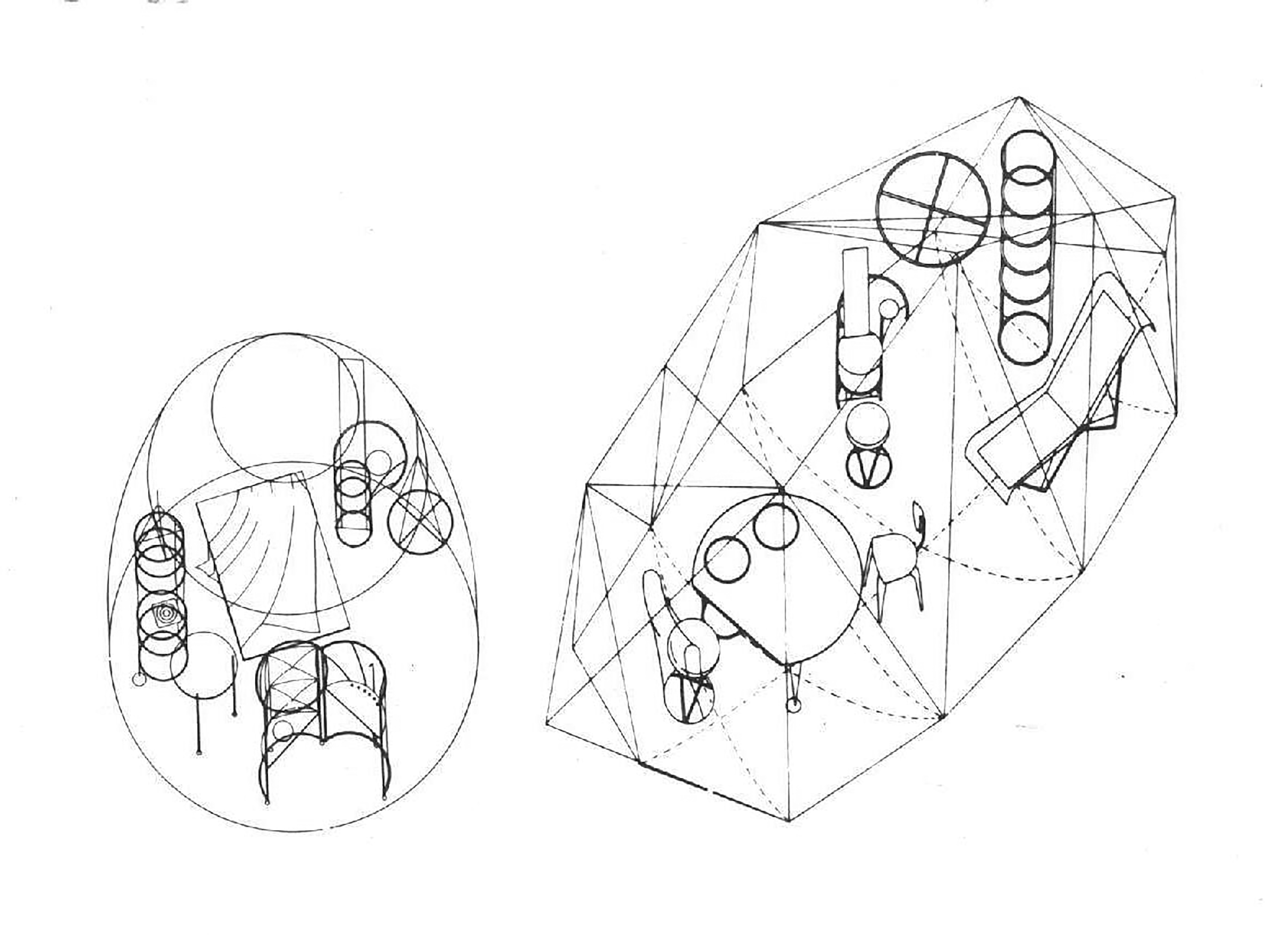

In the work of Absalon—the pseudonym of the Franco-Israeli artist Eshel Meir—there is a notable effort to reconstruct booths in which the artist himself becomes the sole object of study. In his Cells, with surfaces ranging between 4 and 9 square meters (fig. 5), body and space enter into a resonance that exceeds that of earlier architectural projects such as Toyo Ito's Pao I (1985) and Pao II (1989) (fig. 6).5 While the Japanese projects envisioned a cabinet for a nomadic woman entering the expanded city—where having a snack or applying makeup become preconditions for subsequent social interactions—Absalon's work destabilizes the notion of comfort by making the occupant aware of their body, not in relation to the external world, but through direct contact with the walls of his narrow Cells. Because of their restricted dimensions, the inhabitant is compelled to sway or maneuver around the architecture of the cabinet, much like one showering in a cabin that is too small.

Figure 5_ Absalon, Cell 3 (1992) (2.10 × 4.40 × 2.40 m). Source: Wikipedia.

Figure 6_ Toyo Ito, Pao I (1985) and Pao II (1989). Source: El Croquis, No. 71, Toyo Ito 1986-1995 (Madrid: El Croquis Editorial, 1995).

Absalon's early work Sisyphe anticipated this notion of individual struggle and personal transformation through constant negotiation with space. Thus, in his Cells the search is not only for a personal refuge, but for a model of an alternative civilization in which individuality and self-sufficiency are central values. If the idea of a cabinet of curiosities resonates in both Toyo Ito's Pao and Absalon's Cells—through the objects housed within—what distinguishes Absalon is that, instead of contemplating a landscape of brushes, mirrors, or lipsticks, he only has himself: his dimensional body as an object of study. In this sense, interaction and contact against the tight interior space become the primary subjects of reflection and contemplation. As can be seen, rather than presenting a program of ascetic isolation, this body of work reflects on the value of privacy at a time when the individual is increasingly vulnerable and publicly exposed. The Cells, each measuring just under 10 square meters, contain a kitchen, a bed, and a simple bathroom. Absalon described his booths as places of pure introspection, of inward conversation.

Comparing Absalon's work with Vous les entendez… (2015) (1.90 × 2.00 × 1.60 m), a set of booths by Laura Lamiel, the latter appear more like true cabinets of curiosities (fig. 7). Unlike Absalon's Cells, where the body resonates directly with space, Lamiel's booths lack that same corporeal dialogue. Instead, she fills the reduced space of her cubicles with everyday objects—tables, chairs, shoes, lamps. Yet these booths seem recently abandoned. If the inhabitant of Absalon's Cells is the artist himself, the four narrow walls of Lamiel's tiny rooms appear strangely haunted: their floors cluttered with fluorescents or objects that hinder occupancy while asserting themselves as the true center of attention. The booth frames and gathers the remnants of lost solitude and a world of secrets that remain undecipherable. In this sense, interventions such as Alison and Peter Smithson's Patio and Pavilion (1956) resonate: "They are furnished with objects that are symbols of the things we need: for example, a wheel, an image of movement and machines" (Smithson and Smithson 2000, 178). We contemplate a cabinet of curiosities from the outside, as spectators compelled to reflect not on an absent subject, but on the abandoned distance necessary to enjoy and touch this everyday landscape.

Figure 7_ Laura Lamiel, Vous les entendez… (2015). Source: Wikipedia.

With different nuances, the list of artistic examples seems endless. Do Ho Suh, in Rubbing/Loving (2016), creates scaled representations of his intimate spaces—rooms from the houses and apartments where he once lived—which function as cabinets of personal memory. The works allow viewers to walk through the spaces and feel the atmosphere of isolation and introspection. Similarly, Yayoi Kusama, in her Infinity Mirror Rooms (2000), offers an immersive encounter within a repetitive, enclosed space where, once again, as in Absalon's case, the inhabitant becomes the very landscape under study.

Rafael Lozano-Hemmer, in Sphere Packing: Bach (2018), filled a sphere with 1,128 speakers playing different compositions by Bach, transforming sound and space into an intimate bodily experience. But can memories and recollections themselves be stored as objects within these modern cabinets? This is precisely the task Do Ho Suh undertook in Rubbing/Loving (2016). Around the act of collecting objects, dispensing even with the cabinet as container, Elmgreen & Dragset have developed several proposals, such as The Collectors (2009). Antony Gormley, with Blind Light (2007), removes vision from the cabinet altogether by constructing a reduced space filled with fog, evoking a sensation not unlike the mist of water when stepping out of a hot shower.

By the late 1970s, Rosalind E. Krauss had already proposed opening sculpture to territories traditionally reserved for architecture. The influence of her landmark essay Sculpture in the Expanded Field (Krauss 1985) continues to resonate in studies of minimalism and in debates about the disciplinary boundaries between art and architecture. Her effort to problematize "the set of oppositions between which the category of sculpture is suspended" (297) remains highly relevant today. However, while the debate on the expanded field originally referred to the overlapping boundaries between landscape and architecture, today that analogy may be extended to what we might call a contracted field, reflecting on the growing interest in the reduced territories of individuality. Between these two poles, as we have seen, the scale of application has shifted, moving progressively closer to the body and its immediate sphere (fig. 8).

Figure 8_ Overlaid comparative chart of different booths at the same scale. Source: the author.

Booths lead us along a path of retreat, voluntary solitude, secrecy, and small enclosed spaces, all connected by a genealogical line that links intimate refuges with larger aspirations to understand the world. Within this long and rich chain, the presence of individual booths for working with laptops, hydro-massage cabins, UV booths, or even fitting rooms reveals the persistence of the need for personal spaces today. While the cabinet may evoke the isolation embodied by Thoreau's refuge at Walden Pond, booths reinterpreted by contemporary art move beyond mere seclusion, offering instead an exploration of individuality through space. For this reason, such spaces should not be regarded as obsolete within architectural research and development.

When comparing the dimensions and characteristics of contemporary cabinets, it becomes clear that they share a common goal: to provide an isolated environment that fosters individual awareness. These small retreats continue to play an important role in the relationship between the human body and space, for historically they have offered privacy and encouraged concentration since the emergence of the modern individual. Although the forms of privacy have evolved over time, culminating in interventions that address the relationship between the body and its occupied place, technological advances have not entirely supplanted this need.

The historical evolution of individual spaces—from Renaissance cabinets to telephone booths and their later reappearance in contemporary art—highlights the persistence of a fundamental human need: the pursuit of privacy, introspection, and connection with one's own body. The continued relevance of these spaces lies in their capacity to respond to human needs, even in the face of technological and social transformations that periodically reshape daily life. Today, such spaces acquire renewed urgency, given the unprecedented pressures placed on intimate relationships by the overexposure of individuals in a hyperconnected world.

The sensory and proprioceptive dimensions revealed by the artistic interventions studied—whether through skin contact and vision in the works of Absalon, Lamiel, Plensa, and Yayoi Kusama; the dissolution of gaze and body into near-infinity in the works of Turrell and Graham; or the evocation of memory and time in the work of Do Ho Suh—demonstrate the profound connection between the contemporary human body and its immediate space. In these small booths, the potential for interaction is activated at a level of deep experience that often borders on the unconscious, appealing to basic notions of physical contact rooted in the very process of hominization.

Revisiting the lens of proxemics and examining how people use and perceive space from an architectural perspective is therefore essential to understanding the sensory experiences these spaces produce in relation to their design. As the artistic examples have shown, factors such as the distance between the body and spatial boundaries, the restriction of movement, and interaction with objects all shape human perception and the necessary experience of intimacy. By exploring spatial configuration, materiality, light, and sensory interaction, contemporary architecture is called upon to design spaces that respond to the essential need for individual protection, without relying on mere imitation of past typologies. Far from being obsolete, such spaces represent a promising field of research and development for contemporary architecture.

1 Data on telephone booths in the United States can be traced in Kiereini (2018) and Fabry (2016).

2 In the United Kingdom, telephone booths have been repurposed as charging stations or Wi-Fi network nodes, among many other uses (libraries, cardiac resuscitation centers, and even aquariums). This is somewhat ironic, given that it is precisely mobile technology that is considered the main cause of their decline. See BT Archives (2012); "Thousands of Phone Boxes" (2021); and "Thousands of Red UK Phone Boxes" (2021).

3 In this regard, Edward T. Hall identified up to four subzones depending on the type of distance (intimate or personal) and their successive phases (near and far). Intimate distance is where we come into contact with the innermost or internal; at this range, detail is perfect, and touch explores more precisely than sight (whose focal distance is not optimal at these measurements). The far phase of the intimate distance begins at 15 centimeters and extends up to 45 centimeters, precisely as far as the hand can grasp objects. At this point, sight begins to focus efficiently, sounds become distinguishable, and among them, the voice gains presence, usually in a very low tone, a whisper. The next distances come in two steps: from 45cm to 75cm, and then up to 120cm. These dimensions fit almost entirely within those of a common telephone booth. See Hall (1966, 143).

4 In this regard, it is worth mentioning how even cinema has used the booth as a reference to individual isolation, although in some cases it involves forced confinement. This is the case, for example, in Antonio Mercero's film La cabina (1972).

5 Podría hacerse mención a toda una progenie japonesa de cápsulas y recintos mínimos, desde el Capsule Inn, en Osaka en los años 1970, de Kisho Kurokawa, y los ejemplos metabolistas hasta las habitaciones-cabina contemporáneas.