How to Cite: Redondo Pérez, María. "Light, Simulacra, and Script in The Weather Project: Light Art as a Mechanism for Perceptual Control and Behavioral Modulation". Dearq 44 (2026): 67-78. https://doi.org/10.18389/dearq44.2026.07

How to Cite: Redondo Pérez, María. "Light, Simulacra, and Script in The Weather Project: Light Art as a Mechanism for Perceptual Control and Behavioral Modulation". Dearq 44 (2026): 67-78. https://doi.org/10.18389/dearq44.2026.07

María Redondo Pérez

Universidad Politécnica de Madrid, Spain

Received: December 1, 2024 | Accepted: July 30, 2025

The Weather Project is the installation that catapulted Olafur Eliasson to international recognition and stands as a paradigmatic example of the relationship between architecture and contemporary art. This study examines the installation as a device for perceptual transformation, analyzing recurrent variables in contemporary immersive installations such as affect, simulacra, atmospheres, scripts, and anthropocentrism. It argues that visitors' behavior—far from being autonomous—is induced by a lighting scenography that alters the environment and guides bodily movement. The methodology combines critical theory, visual analysis, and planimetric development to demonstrate how hyperreal experiences and atmospheres are produced to exert control over sensory experience.

Key words: The Weather Project, script, atmosphere, light art, performance, hyperreal.

In recent decades, artificial lighting has expanded exponentially in installations designed to redefine the viewer's perception. Designers, artists, and architects have increasingly recognized the capacity of light to create atmospheres within everyday spaces. Due to its physical and phenomenological qualities, artificial light operates as a material that mediates between material and immaterial architectures, enabling the insertion of the virtual into physical space. These approaches position architectural space as a stage capable of being theatricalized through light, thereby inducing emotional and perceptual responses in the viewer (Ramírez Valenzuela 2015). Artificial lighting is not merely a set of technical processes; it functions as a contemporary architectural tool and resource. Lighting designers and artists anticipate the behaviors and emotions their works will elicit, drawing on shared repertoires of images that resonate with viewers' prior experiences. Certain lighting designs invite contemplation, communion, or introspection, and through these invitations—mediated by imagery—modulate the behavior of visitors who encounter them.

The most compelling demonstration of light's capacity to alter bodily perception is found in light art—an artistic movement that uses artificial light as both medium and material to construct installations that transform the spaces they inhabit or redefine the viewers' perception. Light art is a cornerstone in the production of intangible realities and represents an extreme form of perceptual modification. These installations construct virtual, immaterial worlds, transporting viewers into dreamlike universes that either re-enchant space or evoke an uncanny experience within otherwise familiar settings (Bennett 2001, 5). Light captures our attention, builds narratives, and creates states of consciousness that allow for reflection on our physical condition (French 2017). Since its emergence in the 1960s, light art has been increasingly integrated into museum programming, exhibited at larger scales, and with escalating emotional depth.

By the late twentieth century, museums had become the cultural apex of Western cities, assuming significant influence in both social and urban spheres. In his presentation "34 Museums as Soccer Stadiums," Rem Koolhaas underscores the interdependence of economy, architecture, and art. He observes that "the world of museums has expanded in exact proportion to the rise of Wall Street" (Koolhaas 2014), a correlation evidenced by the global proliferation and increasing scale of museums. As a paradigmatic case of this exacerbated growth of architecture and the amplified role of art in contemporary society, Koolhaas cites the Turbine Hall of Tate Modern to illustrate the challenge artists face in filling such vast spaces. These monumental interiors, he argues, dwarf the human scale and, "in order to fill spaces like this, artists are forced into a kind of almost apocalyptic mode because somehow only very strong emotions register, this is obviously not a space that you can fill with delicacy although some projects have actually tried" (presentation excerpt, 09:42–10:06).

The Weather Project is the installation that catapulted Olafur Eliasson to international recognition and has become a paradigmatic example of the relationship between architecture and contemporary art. Installed in the Turbine Hall, it presented an apocalyptic sun that flooded the entire space and invited visitors to gather beneath its light. Although initially framed as a reflection on the environment and climate change, the installation offered a sensory experience that simulated extreme atmospheric conditions to raise awareness of the planet's fragility. Yet, this article argues that lighting scenography operates primarily as a device of affective and behavioral control, modulating audience behavior and expanding the installation's meaning beyond its explicit environmental message. Photographs show visitors dispersing across the entire space, moving freely, walking, lying on the floor, and engaging in various activities. One might assume that such behavior reflects individual autonomy; however, if that were truly the case, those same actions would have occurred on other occasions in the Turbine Hall, rather than disappearing entirely once the exhibition ended.

Given the prominence this installation attained within the cultural landscape and its now paradigmatic status, it is worth asking what made this installation so memorable that, two decades later, it is still being discussed. Which elements continue to resonate within contemporary culture and the contemporary imaginary? And what specific relationship emerged between the hall, the art installation, and the museum visitors?

Building on Koolhaas's hypothesis about how The Weather Project transformed the Turbine Hall through the forms of occupation it elicited, this study analyzes the installation through a set of variables and themes common to contemporary environments that modify visitor behavior: affect, simulacra, atmosphere, script, and anthropocentrism. The analysis unfolds in two phases (fig. 1), combining visual analysis and critical theory to examine the mechanisms of perceptual control at work in light art installations. The first phase addresses the creation and construction of the installation, from the conceptual proposal to its technical implementation within the hall. Its theoretical framework engages the concepts of atmosphere, simulacra, and the hyperreal (Baudrillard 1978; Deleuze and Guattari 2002), while the practical component reconstructs the architectural and lighting system through plans, analytical sketches, and technical documentation. The objective is to identify how an atmosphere capable of inducing specific behaviors is produced. The second phase focuses on the activation of the public and the ways this was manifested through movement and actions in the hall. Here, the installation is examined through the lenses of the Anthropocene, affect (Clough 2008), and script (Latour 1992). Photographs of the installation are used to map people's positions and activities, identifying the emergence of groups, tendencies, and spatial trajectories, which demonstrate that space is not perceived neutrally but scripts the viewer's bodily experience. This analysis employs tools from architectural criticism and contemporary art to foreground interactions among body, space, and light. Such an approach enables a transversal reading that links spatial practice and bodily experience, revealing the technologies of subjectivation embedded in these devices. Ultimately, the study argues that The Weather Project functions as a scenographic script, encoding perceptual experience and modulating collective behavior through a luminous atmosphere.

Figure 1_ Diagram outlining the analytical approach to the installation. First, the atmosphere of the installation is examined. Second, visitor activity is analyzed. The conclusions synthesize both dimensions. Source: the author.

The Turbine Hall at Tate Modern is a vast, 3,300-square-meter space that is 26 meters high and serves as the museum's main entrance. In this massive space, Olafur Eliasson installed, near ceiling height, a semicircular steel structure measuring 15 meters in diameter, concealed behind a projection screen. Behind the screen, hundreds of yellow monochromatic luminaires cast a uniform light that completely flooded the hall (fig. 2). The central skylight was blacked out and covered with a ceiling of aluminum mirrors that served three functions: they completed the illusion of a full sun, perceptually doubled the hall's space (fig. 3), and redirected visitors' attention toward their own reflections rather than the installation itself. To this imposing scenography, Eliasson added a glycol-based fog, intended to diffuse perception of the hall's structural vastness and disorient visitors within the environment, prompting movement as a means of orientation. In addition, to prevent any intrusion of external visual information that might disrupt the constructed atmosphere, the museum's internal windows were covered with painted vinyl films, following the same strategy used for the skylight.

Figure 2_ Image of the artificial sun, showing the structural framework, the boundary with the aluminum mirror, and the position of the luminaires behind the screen. Source: Diagram prepared by the author based on photographs of the installation.

Figure 3_ Section showing how the nave's volume is phenomenologically doubled by the aluminum mirror. Source: the author.

The installation sought to evoke the image of the sun setting into the ocean, the reflections in Munch's works, and the proto-industrial descriptions of London in the writings of Charles Dickens, Oscar Wilde, or Arthur Conan Doyle—authors who depicted a city where the sun had died and fog rendered visibility nearly impossible. Through these simple elements of light and fog, the work aimed to transpose London's weather into the building, producing a dystopian, artificial, synthetic landscape—a simulacrum.

Simulacra have assumed a central role in contemporary society. Ramírez Valenzuela's (2015) notion of everyday spaces rendered theatrical through artificial lighting intersects with Debord's (1967) idea that images are not mere representations of reality, but are constructed, selected, and manipulated by different media to serve specific ideological, economic, and cultural functions. For Debord, the dominance of the economy over life reduces being to having, and ultimately having to appearing. In this sense, much of contemporary reality consists of representations of what is taken to be real. Similarly, Jean Baudrillard observes that contemporary Western society seeks to substitute reality with symbols—a substitution so pervasive and radical that any notion of an original reality has vanished: everything is an imitation of an imitation (Baudrillard 1978). Deleuze takes this further with the concept of the hyperreal: a world in which there is no longer an original to imitate—everything is copies of copies—producing a reality composed entirely of references to imitations (Deleuze 1968). Where, then, does the value of these simulacra lie? The sun and fog inside the Turbine Hall succeed not because they realistically imitate a recognizable natural landscape, but because they derive value from modifying the imaginaries we already possess (fig. 4). When artificially reproduced fragments are decontextualized, they radically transform the site's original meaning (García Píriz 2018, 106). The hyperreal acquires meaning when a reference is evoked yet narrated differently, displaced from its context, or fused with other references, so that everything becomes confused. As Hal Foster (2013, 213) argues, Eliasson's installation reconstructs both natural and technological worlds, revealing that contemporary nature is itself a weather project and that phenomenological experience is mediated through image.

Figure 4_ Collage of images of the installation. Source: the author.

The creation of an easily recognizable atmosphere, its deliberate decontextualization, and the shift of focus towards the viewer and their relation to the work are central to the spatial construction of The Weather Project. This second section analyzes its phenomenological architecture and the triggers that shape the installation's overall configuration. The issues raised in the first section underscore the theatricality of the Turbine Hall, positioning visitors as actor-protagonists whose performance is essential for the scene to make sense (fig. 5). Beyond the material installation, a crucial component lies in the active role assigned to the visitor, articulated through the installation's third element: the mirror. Eliasson often invokes the notion of "seeing ourselves seeing"—an introspective awareness of perception itself, wherein the viewer becomes conscious not only of what is seen, but of how seeing occurs (Eliasson and Irwin 2007). As Hornby argues, it is the primacy of human experience and encounter—not weather, as the work suggests—that situates Eliasson as a conductor in the age of the Anthropocene, orchestrating time, weather, and even the viewer (Hornby 2017, 65). In this sense, the actions of visitors who agree to participate in the performance become part of the artistic process, aligning with the dynamics of spectacular alignment criticized by Debord. Consequently, the work operates within the regimes of Baudrillard's simulacra or Deleuze's hyperreal.

Figure 5_ Collage of images and videos centered on visitor activity, sourced from Instagram. Source: the author.

Light art installations operate within the realm of phenomenological and affective experience. Through light, they create "environments that blur the real with the virtual, or sensations that scarcely belong to us yet nonetheless address us" (Foster 2013). These installations seek to transform the observer into part of the artwork, which acquires meaning through the observer's interpretation at a subconscious level. This aesthetic experience aligns with Kant's (1876) notion of the sublime, defined by encounters with grandeur, power, or immensity that exceed our capacity for comprehension or apprehension. Therefore, these works must be processed in two phases: first, the subject is overwhelmed—often emotionally—by the magnitude of the scene; second, they recover and experience a renewed sense of personal power (Foster 2013, 211). At that point, the work becomes real for the observer. The artwork, therefore, requires the presence of bodies that interact with it in order to exist, as it acquires meaning through their interpretation. As Merleau-Ponty argues, the world is what we perceive and live (1993); in phenomenological terms, virtual experiences are thus no less real than material ones.

The success of such installations lies in their capacity to articulate the blurred boundary between the physical body and the phenomenological body. According to Murray and Sixsmith, these works aim to "destabilize the experiential boundaries of a person's body, thereby partially freeing the phenomenological body from the experiential constraints of a person's physical presence in the real world" (1999, 319). This separation between the physical body and the phenomenological body enables a modulation of bodily behavior in space (Redondo Pérez 2025). A central concept in this context is affect. Patricia Clough (2008) defines affect as the body's capacity to affect and be affected—that is, its potential for action and connection. Deleuze, in turn, conceives of affect as a form of corporeal meaning: forces, intensities, and capacities that arise through encounters between human and non-human bodies. It is a force that passes through bodies and transforms them. Art and aesthetic experience, for Deleuze, are not expressions of subjective feelings, but a generator of affective intensities capable of destabilizing the subject (Deleuze 1984).

Bruno Latour (1992) introduces the concept of script to describe the subtle prescriptions that technologies inscribe into human behavior. A script implies that nonhuman entities carry implicit instructions about how we are to engage with them, shaping conduct without explicit directives. This relational logic is inherent to such artistic installations and to our behavior in museum spaces. Under this premise, the nonhuman—in this case, light—structures the behavior of the bodies that encounter it. Acts such as contemplating, approaching, sitting, moving, relaxing, or touching are all part of the script: actions performed not because they are mandated, but because the environment silently calls for them. Accordingly, some installations encourage overt performance while others elicit more restrained participation, even when visitors remain unaware that they are performing at all (Duncan 1995, 1–2).

In the case of installations, the major shift from other types of artworks lies in the separation of art from the gallery's physical boundaries and its placement at the center, compelling visitors to move around the installation (Reiss 1999). This activation and decentralization of the subject disrupt the paradigm of a central perspective of the body in relation to the artwork. Light art installations refuse an ideal vantage point, displacing the observer's static position in favor of active engagement (Bishop 2005, 13). In The Weather Project, this condition is pushed to its extreme. The installation is not designed to be observed from a fixed location or to be circled or seen from multiple angles. Instead, it is conceived to "look and be looked at and be aware of how we look;" it must be traversed—through play, through presence, and through watching others—filtered by the installation itself (García Píriz 2018, 109). The work incorporates the multiple perspectives of the decentralized subjects in motion, rendering visitors simultaneously observers and observed (Hornby 2017, 63). It seeks an experiential response from its subjects:

"What surprised me was how people became very physically explicit. I pictured them looking up with their eyes, but they were lying down, rolling around and waving. One person brought an inflatable canoe. There were yoga classes that came, and weird poetry cults doing doomsday events. When President Bush visited London, some people arranged themselves on the floor to spell "Bush go home" as a protest—to do that in reverse so it read in the mirror is actually pretty difficult. I liked how the whole thing became about connecting your brain and your body. That I did not foresee." (Jonze, Eliasson, and Behmann 2018).

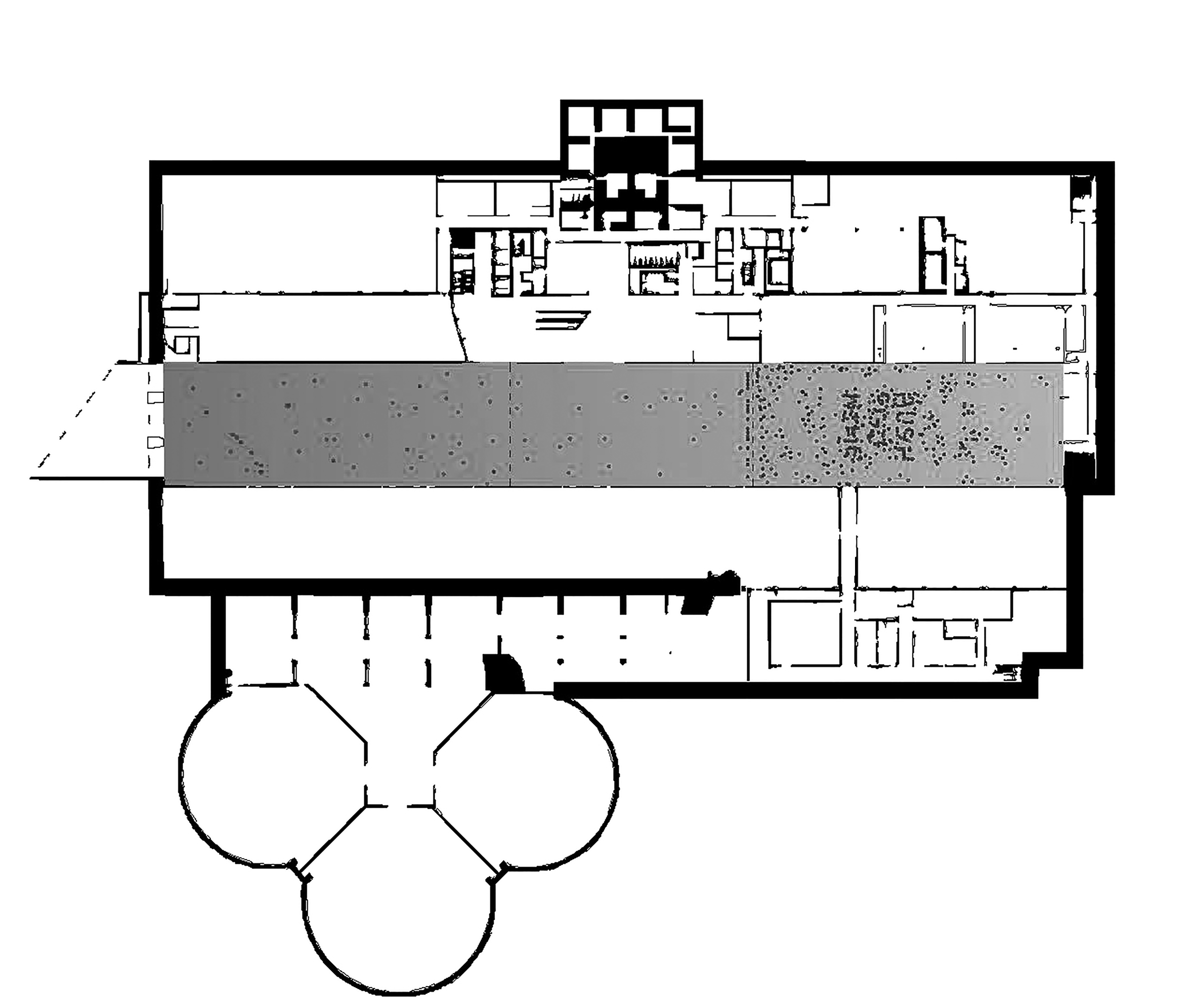

Olafur Eliasson's installation was defined by its use of atmosphere as the principal element, deliberately eschewing any concrete physical object that could serve as a focal point. This tabula rasa facilitated free movement and spontaneous associations, prompting visitors to engage in a range of activities and performances (fig. 6). These behaviors deviate significantly from those typically deemed appropriate within cultural spaces. Yet it was the installation itself that made them possible and even encouraged them. This phenomenon can be understood through Latour's concept of the script: the spatial design and reconfiguration of the Turbine Hall facilitated and structured visitor interactions. Moreover, participation generated synergies, drawing new actors into play who, in turn, influenced one another through their actions. Ultimately, it was the presence and movement of people that endowed the work with meaning, underscoring the role of collective interaction as a constitutive element in the interpretation and experience of the installation.

Figure 6_ Mapping of people's movement derived from photographs of the installation. Source: the author.

Position guides location, and location guides meaning-making. Bodies and objects moving through space and exerting influence on one another: This foundational image of actor-network theory is extraordinarily useful for cultural sociologists. Art museums offer a very visible instance of this. Examining the "dance of agency" among human and non-human actors, we see how art objects, labels, and people act upon each other to shape interpretation. How a curator mounts an exhibition and how people move through it emplace the art works. This emplacement directs how audiences experience the art. By observing this "choreography" we develop a more robust theory of meaning-making that moves beyond cultural sociology's exclusive focus on how cognitive presuppositions of audiences inform and constrain people's interpretation of the cultural objects. (Griswold, Mangione, and McDonnell 2013, 360).

Ultimately, the work becomes a phenomenological experiment in the control of atmosphere and of the visitor (Hornby 2017, 73). The sun functions as the lure, the fog is the auxiliary medium of enchantment, the mirror as the trigger, and the performances and bodily affects as the installation's true outcome.

The Weather Project stands as a paradigmatic example of the relationship between contemporary art and architecture. It also highlights the central role that visitors have assumed within the twenty-first-century museums, reflecting a broader emphasis on active interaction among subjects, artwork, and exhibition spaces. Moreover, the installation engages with current debates on the mediation of contemporary Western culture through images and the impact of such mediation on the realities we inhabit. Given its enduring resonance over two decades, Eliasson's installation offers a compelling case study in how light and other phenomenological tools can be used to orchestrate bodies within space.

The defining feature of the installation lies in its ability to transform a concept of immense scale—one that fully encompasses the immense space of the Turbine Hall—into a stage where attention is redirected to visitors and their actions, restoring human agency within that immensity. Although less conspicuous than the artificial sun, the mirror plays a pivotal role by enabling participants to "see themselves seeing." This device facilitates collective coordination, inviting play and experimentation on the tabula rasa that the hall becomes under light. The absence of physical objects—elements that might otherwise serve as attractors—intensifies this dynamic; instead, moving bodies influence one another, generating synergies across a shared phenomenological space.

This installation opens opportunities for future research into the factors underlying the success of comparable works. Beyond offering aesthetic experiences, light art installations in museums may be understood as small-scale experiments conducted in controlled settings—experiments that can later be translated to broader applications in the urban context. From this perspective, analyzing how people interact with such works becomes essential to understanding the contemporary city as a phenomenological laboratory.

Urban lighting has intensified sensory experience in public space. This shift is evident in the exponential rise of artificial light festivals since the 1980s, which transform the city into a stage for installations and seek the direct participation and interaction of those who encounter them. Examining how bodies engage with phenomenological space not only reveals these dynamics but also provides critical tools for designing contemporary cities with greater responsibility and attention to inhabitants' well-being.

In this context, The Weather Project should be understood not merely as a large-scale artwork, but as a functional prototype of sensory and affective spatial management—effective precisely because it transforms the museum into a behavioral experiment. By redirecting attention from object to experience, from form to atmosphere, the installation anticipates an emerging urban logic in which architecture operates less as a container and more as an interface, with lighting design as a key vector of social organization.