How to Cite: de Lacour, Rafael. "From Action Painting to Architecture in Transformation: Picasso, Pollock, Duchamp, and Matta-Clark". Dearq 44 (2026): 79-90. https://doi.org/10.18389/dearq44.2026.08

How to Cite: de Lacour, Rafael. "From Action Painting to Architecture in Transformation: Picasso, Pollock, Duchamp, and Matta-Clark". Dearq 44 (2026): 79-90. https://doi.org/10.18389/dearq44.2026.08

Rafael de Lacour

Universidad de Granada, Spain

Received: December 1, 2024 | Accepted: August 4, 2025

Between 1949 and 1952, Pablo Picasso, Jackson Pollock, and Marcel Duchamp were photographed, respectively, drawing in the air with a small electric light, painting from all sides of a canvas, and descending a flight of stairs. These photographic records reveal a capacity of expression through bodily movement that corresponds directly to artistic action. In 1977, twenty-five years later, Gordon Matta-Clark was filmed in a large-scale intervention, creating a three-dimensional ladder within which new possibilities of spatial modification could be explored. This review and comparison of these experiments demonstrates how the perception and interaction of body, space, and architecture converged to open new avenues for architectural transformation.

Keywords: Action, movement, body, Pablo Picasso, Jackson Pollock, Marcel Duchamp, Gordon Matta-Clark.

This study offers a critical review of three well-known experiments in the art world of the mid-twentieth century, featuring three of the century's most influential artists—Pablo Picasso, Jackson Pollock, and Marcel Duchamp—and reveals the relationship between movement and artistic creation through action. Based on a bibliographic and documentary reconstruction of these events, this study proposes a corresponding link to the architectural field by analyzing a later experiment in bodily action, this time in an architectural context. The focus in this case is the revolutionary artist-architect Gordon Matta-Clark, with an in-depth look at one of his final works, which has recently gained renewed relevance following the release of previously unseen footage of the event. Building on this, a study of updated audio-visual, photographic, and research materials has enabled the identification of future lines of exploration regarding spatial perception and movement in art, offering ongoing opportunities for architecture.

The first objective of this study is to identify and analyze relevant artistic experiments in which body and space are closely tied to the artist's action. From this starting point, it seeks to trace the transfer of these ideas to experiments that explore the connection between art and architecture, thereby enabling their application to concepts of the architectural perception of movement and the potential for a new architecture.

The mid-twentieth-century works analyzed here, created by artists originally working in painting, represent both a transgression and an expansion beyond the spatial limits of the artwork through the incorporation of the artist's own body. From this point onward, emphasis on the body would steadily increase, often to the detriment of painting itself. On the one hand, the process came to take precedence over the final product, which may help explain the ephemeral character of these works. On the other, the channels of transmission and expression were also changing, with photography introduced to document the process. This implied a staging of the event, and the kinesthetic character of the artist's bodily action effectively liberated the artwork from its final outcome, radically breaking with established conventions. This shift entailed a loss of form, the negation of drawing-based painting, an emphasis on intuition, and a change in scale.

I paint objects as I think them, not as I see them.

— Pablo Picasso (Klingsöhr-Leroy 2006, 84)

In 1949, the Albanian photographer Gjon Mili visited Pablo Ruiz Picasso at his home in Vallauris, in the south of France, on an assignment for Life magazine for an unusual article. Mili had studied electrical engineering at MIT, where, in 1937, he met photographer and electrical engineer Harold Edgerton, who had been working since 1926 on the development of stroboscopic photography, using a light source that emitted rapid successive flashes. By the late 1940s, Mili had perfected the technique of capturing, in a single image, the textures produced by rapid movements, which created the impression of frozen time.

According to Life, Picasso gave Mili fifteen minutes to conduct the experiment. They worked in an almost dark room, with only a few faint rays of light entering through the window blinds. The photographer used two cameras—one for a lateral view and one for a frontal view—and proposed that Picasso draw in the air with a small lightbulb connected to an electrical cable, which he would capture with the camera shutter open while adjusting the exposure time. Although Mili had initially intended to record only the movement of Picasso's hand and arm, the patterns the artist traced revealed the movement of his entire body. The experiment thus evolved from what had been conceived as light painting to something that could more accurately be described as space drawing (fig. 1).

On viewing the initial results, Picasso became fascinated by the process and posed for five additional sessions, producing nearly thirty such drawings featuring his well-known centaurs, bulls, and Greek profiles. The photographs of these experiments were exhibited at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York from January 25 to March 19, 1950, alongside other images by Frank Capa of Picasso, his partner Françoise, and their two children, Paloma and Claude (Cosgrove 1949).

By using two cameras, Mili was able to show the same drawing from different angles, enhancing its three-dimensionality. The drawings did not appear flat, but slightly spherical, as they were inscribed in the space surrounding the light source. These still shots also reveal the artist's postures as he drew—crouching, standing upright, his arm raised or extended outward—conveying both his concentration and his enthusiasm for the possibilities of photographic expression. The images, which capture the creative act in its entirety, thus constitute a unique record. And although the authorship of these intangible air drawings is unmistakably Picasso's, it is equally true that the singularity of the stroboscopic technique revealed the corporeal expressiveness of the brilliant Spanish artist as never before.

Figures 1 and 2_ Gjon Mili. Picasso drawing with light, 1949. Source: Life magazine.

I work from inside to outside, as in nature.

— Jackson Pollock (Elger 2008, 58)

In June 1950, the magazine ArtNews sent photographer Rudy Burckhardt to document Jackson Pollock working in his Long Island studio, to which he had moved from Manhattan in 1945. A few weeks later, Hans Namuth, a young photographer from Harper's Bazaar, also visited the studio to take photos for an article by the critic Robert Goodnough entitled "Pollock Paints a Picture," published in May 1951.1 The year 1950 was Pollock's most productive, marking the beginning of his series of large-format drip paintings. After an early figurative period, he had discovered new possibilities in abstract expressionism and, starting in 1947, began experimenting with the so-called dripping technique. He had learned this from his friend Max Ernst, who, in the early 1940s, used an oscillation process in which paint was allowed to drip in a circular motion through holes made in a paint can onto a cloth laid out horizontally. The intuitive movements with which this was done were both free from automatism and charged with action—hence the later concept of action painting.

In the mid-20th century, painting was undergoing a transformation: the art object itself was losing prominence, while the technical process and the act of making took center stage. Editors at the magazines sought a closer look at the painters' working methods, and ArtNews intended to show Pollock painting in his studio.2 However, when Burckhardt and Goodnough arrived, his painting Number 32 was already finished. Pollock pretended to drip paint onto the canvas, but the resulting photographs were rejected for failing to capture the process, delaying the publication of the article (Kalb 2012, 9). During the later visit, Namuth was able to photograph the artist painting for an hour and half, capturing both his movements and his method of flinging paint onto the canvas (Cruz 2022, 240). Using slow exposures, he produced blurred images that conveyed this vibrant action in rapid sequences, depicting Pollock's body leaning over his work in a state of concentrated tension. The photographs sought to follow the rhythm Pollock brought the act of painting—slow at first, gradually accelerating, eventually resembling a dance as he hurled thick streams of black, white, and rust-colored paint onto the canvas (fig. 3).

These quick, disconnected movements were dictated by the large scale of the canvas and were captured by Namuth in both overhead and mid-level shots that conveyed the overall atmosphere of Pollock's method. He paced around the canvas, laid flat on the floor like a spatial tapestry, then approached it to apply paint from every side, producing delicate patches of color. He used his wrist and arm in rhythmic, intuitive gestures, although his brushes and other tools—such as wooden sticks—rarely touched the canvas. None of this resembled the manual dexterity and precise brushwork on which rational painting had traditionally relied (fig. 4).

Figures 3 and 4_ Hans Namuth, Pollock painting, 1950. Source: ArtNews magazine. © Hans Namuth Estate. Courtesy of the Center for Creative Photography, University of Arizona.

With these images, a visual experience involving painter, photographer, and viewer was created, conveying the emotions released during the act of painting—shifting from apparent brutality to a sense of calm in a kind of ritual dance. The photographs reflect the artist's use of his body and the energy behind his technique. The recording of the event thus became an essential component of artistic creation. From this point onward, Pollock's work could no longer be understood without an awareness of his process.

I have no ideas, I only make discoveries.

— Marcel Duchamp (Tomkins 1996, 257)

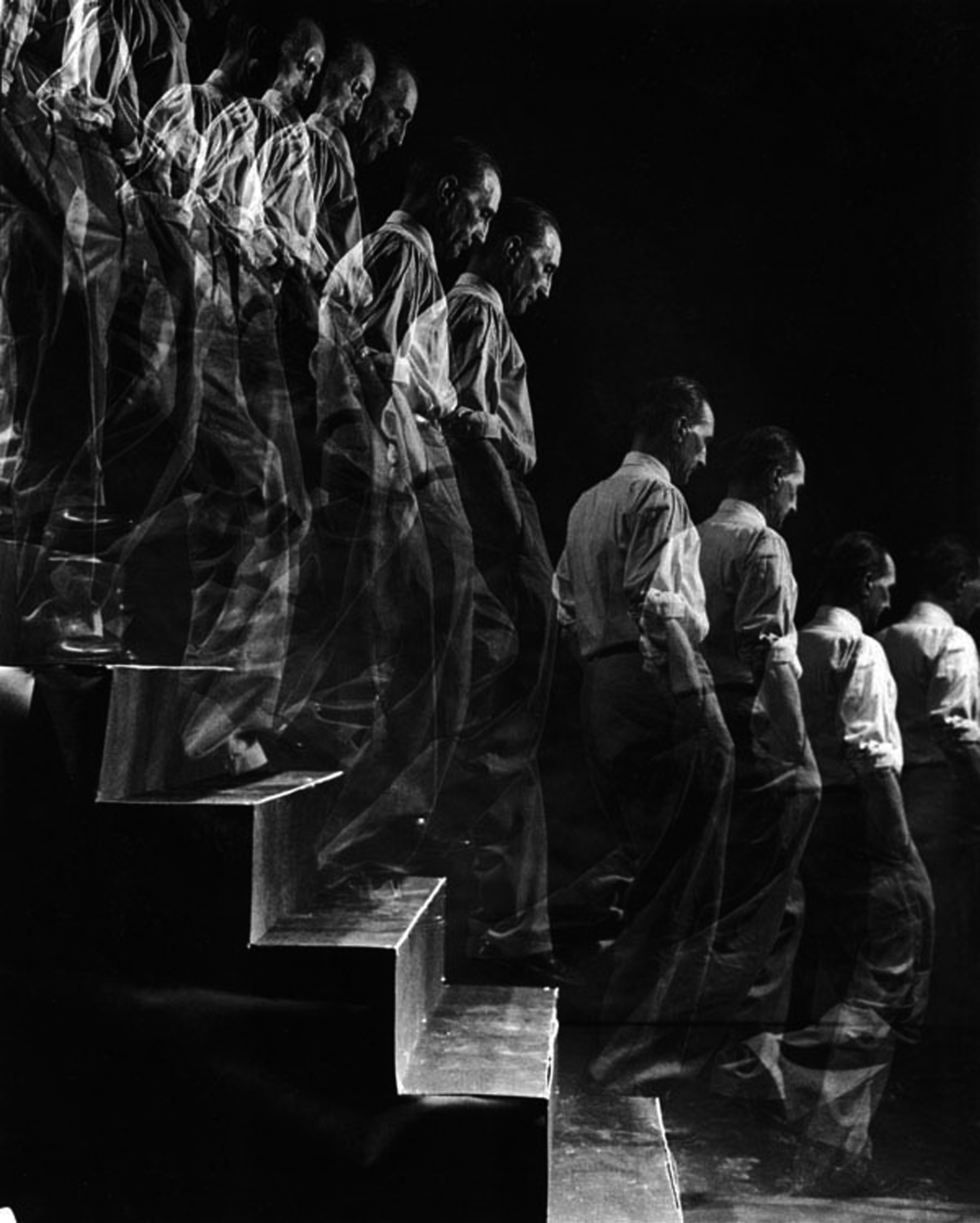

In 1952, photographer Eliot Elisofon visited Marcel Duchamp to take photographs for a Life magazine article by Winthrop Sargeant entitled "Dada's Daddy," published on April 28, 1952. Elisofon proposed creating time-lapse images of Duchamp descending a staircase, in clear homage to the artist's famous work, Nude Descending a Staircase No. 2 (1912). That painting had caused an uproar when it appeared in New York's Armory Show in 1913—the first exhibition of avant-garde European art in the United States—for depicting the nude not as an ideal of beauty in a traditional reclining position, but as an unrecognizable figure engaged in the mundane act of walking down a flight of stairs (fig. 5).

Figure 5_ Marcel Duchamp, Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 2, 1912. Source: Philadelphia Museum of Art.

The original painting depicted a moving figure through a succession of superimposed images, inspired by stroboscopic photography and the chronophotography of Étienne-Jules Marey, as well as by other twentieth-century studies of motion photography. Duchamp's work has a direct relationship to a series of images produced in 1887 by the English photographer Edward Muybridge, titled Woman Descending the Stairs. These experiments were also connected to others of the period, such as those by the futurist artists Arturo and Anton Giulio Bragaglia, who employed a technique called photodynamism, using prolonged exposure times and continuous light sources.3 While Cubism was seen as capable of representing time in two dimensions, in this painting Duchamp succeeded in capturing movement in a static form. Elisofon's suggestion that Duchamp descend the staircase himself was entirely deliberate, as evidenced by the correspondence between the painting and the photograph, as well as by the succession of individual frames (fig. 6). In fact, Duchamp's well-known remark to Elisofon as the shot was being prepared was, "Don't you want me to do it nude?" (Tomkins 1996, 379). This homage thus served as an acknowledgement of the influential role Duchamp had exercised—from his first readymade onward—over subsequent generations of creators, from Jackson Pollock to Andy Warhol and John Cage. His influence would endure in the following decades, particularly in conceptual and action art, and especially in performance art, whose development in the late 1950s owed much to Fluxus and related movements. Among these, as the next section will show, Gordon Matta-Clark would come to embody the transfer of Duchamp's legacy to the field of architecture—although, rather than dealing with architectural readymades, his work might be defined as ready-to-be-unmade, as he himself described it (Matta-Clark 2020, 53).4

Figure 6_ Eliot Elisofon, Marcel Duchamp descending a staircase, 1952. Source: Life magazine.

I work similar to the way gourmets hunt for truffles.

— Gordon Matta-Clark (2020, 77)

The three episodes analyzed—in which Picasso, Pollock, and Duchamp were photographed between 1949 and 1952—document the expressive power of movement in the work of these three artists, arguably the most influential of the twentieth century. They also help to illustrate the evolution art was undergoing in the second half of the century, as well as the growing importance of documenting the work and the possibilities of communication, including the emergence of movement-based performance art.

In effect, drawing in the air, painting on a horizontal canvas, or moving one's body through space marked a shift from the bidimensional to the tridimensional, as well as a turn toward life itself, as Cage would later advocate. For him, "art is a sort of experimental station where one tries out living" (2012, 139). Bodily action thus became a means of rejecting conventional channels, blurring disciplinary boundaries in a disruptive manner that brought painting closer to dance—just as architecture and sculpture would also converge. The new dance (performance) and the new sculpture (minimalism) shared a common focus on the "ways of organizing and grasping the movement of bodies in space" (Michelson 2013, 37).

Through this performative attitude of the artist's movement, the autonomy of the discipline was called into question. Painting began to incorporate the body into artistic practices from which it had previously been excluded; indeed, the body became a trigger for challenging the ontological foundations of expression and language. In architecture, however, the presence of the body posed an additional challenge, ultimately finding expression in the dissolution of constructed boundaries and a renewed emphasis on the experience of habitation.

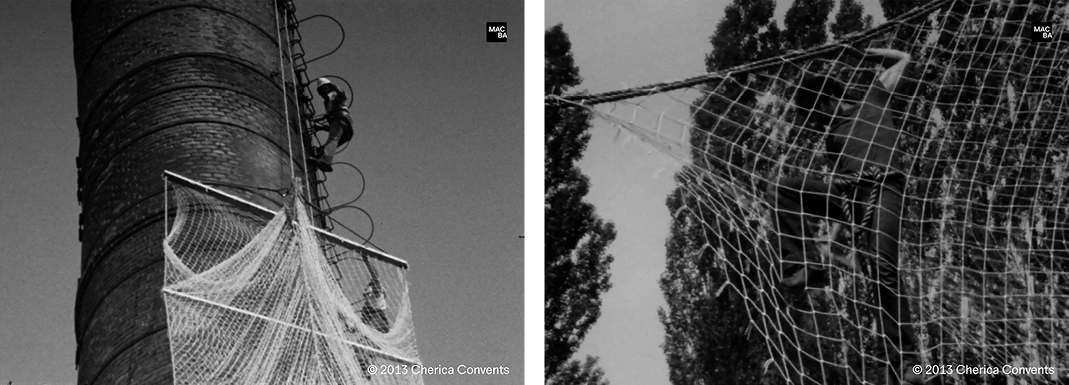

Twenty-five years after the cases analyzed above, the movement through which action-based art once again transcended space and entered architecture was led by the inimitable figure of Gordon Matta-Clark, whose work questioned space and its relationship to the human body. By examining how he employed his body and its movements in the various photographic records preserved in his archives5, it becomes possible to identify the key aspects of the spatial—and ultimately social—transformation of the architectural medium that he proposed (Urpsrung 2016, 124). In June 1977, Eric "Cherica" Convents filmed Matta-Clark and his German assistant over three days in preparation for the unveiling of the installation he titled Jacob's Ladder, created for the contemporary art exhibition Documenta 6 in Kassel, Germany. Directed by Manfred Schneckenburger, that edition focused on process, large-scale performance, and documentation. Although three potential versions were initially envisioned, given practical constraints Matta-Clark ultimately constructed a "ladder" from a flexible system of ropes and cables—a spatial structure resembling a long triangular net (Diserens and Enguita 1993, 274). This triangular tunnel extended from the ground to the top of a thirty-story industrial chimney (fig. 7).

Figure 7_ Cherica Convents, A Jacob's Ladder, remembering Gordon Matta-Clark, 2012-2013; single-channel video, color, sound, 36 min 9 s. Source: © Cherica Convents / MACBA Collection, MACBA Consortium. Courtesy of Cherica Convents and MACBA.

The lower side of the structure was reinforced with a series of wooden battens, placed two meters apart to form a kind of floor. The three cables forming the edges of the inclined triangular prism were attached to the top rung of the steeplejack ladder running up the side of the brick chimney. These cables were then wrapped in a mesh nylon rope that Gordon Matta-Clark, with the help of Jane Crawford, had spent several days and nights weaving in a rundown hotel room (Diserens 2003, 106).

While the exterior image of the structure was imposing, the view from within produced a profound experience of ascension, heightened by the visual vanishing point in the sky that seemed to stretch toward infinity (fig. 8). The title Jacob's Ladder was a clear allusion to the book of Genesis, which recounts Jacob's dream of a staircase upon which angels ascended to heaven and descended to earth. Like his earlier Descending Steps for Batan (April 1977), it was an homage to Gordon's twin brother, Batan, who had committed suicide the previous year by jumping from the window of the artist's studio (Donoso 2016).

Figure 8_ Gordon Matta-Clark, Jacob's Ladder in Documenta 6, 1977. Source: © The Estate of Gordon Matta-Clark / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Courtesy of The Estate of Gordon Matta-Clark and David Zwirner.

Although the piece appears to be merely a symbolic vector attached to a brick chimney stack, it in fact formed a transitable space through which a person could physically pass. Depending on one's confidence in the strength of the mesh structure, the braver visitors (and those not susceptible to vertigo) were able to move from one batten to the next and climb the great catenary themselves. The risk of falling was far less than what Matta-Clark had faced during his own ascent, given the minimal safety measures taken in securing the structure to the tower (Diserens 2003, 106).

Images of the event show Matta-Clark climbing the chimney's steeplejack ladder as the structure was being raised and the cables pulled taut (fig. 9). He also appears crawling inside the prismatic triangular space of the netting, precariously balanced and gripping the mesh sides (fig.11). The perspective of this shot highlights the verticality of the space and intensifies the sensation of risk. Matta-Clark himself described Jacob's Ladder as stemming from the idea of drawing in space rather than drawing with things. The installation addressed the liberation of space by occupying space that was already free, as opposed to liberating space through cuts in existing structures, as in his earlier works (Convents 2013).

After lying dormant in the photographer's archives for 35 years, the original 16 mm documentary footage of Jacob's Ladder and its 1977 construction has recently been released by Convents in re-edited form (fig. 10). The recovery of this footage in 2013 offers essential insight into both the constructive and experiential dimensions of this bodily engagement with space. Although the installation has received less attention than Matta-Clark's better-known cuttings, it has a significant impact of its own—one that is crucial for understanding the broader context of his practice and his relationship to it.

Figures 9 and 10_ Cherica Convents, A Jacob's Ladder, remembering Gordon Matta-Clark, 2012–2013; single-channel video, color, sound, 36 min 9 s. Source: © Cherica Convents / MACBA Collection, MACBA Consortium. Courtesy of Cherica Convents and MACBA.

Figure 11_ Gordon Matta-Clark, Jacob's Ladder in Documenta 6, 1977. Source: © The Estate of Gordon Matta-Clark / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Courtesy of The Estate of Gordon Matta-Clark and David Zwirner.

The value of this work has also gained importance for its connections to Matta-Clark's pre-cutting pieces, for which he constructed a number of similar artifacts. His career, in fact, began in 1968 with an outdoor installation consisting of a network of ropes and knots that served as a functional bridge (Diserens 2000, 47). Rope Bridge was designed to span a waterfall near Cayuga Lake in New York State, in the same year that Matta-Clark completed his architectural studies at Cornell University. This fragile structure, which swung dangerously close to the turbulent waters, featured an element of dynamism not only through its oscillating movement, but also through its slight, ephemeral character in relation to natural forces (Candela 2007, 25). This first outdoor installation was neither filmed nor photographed with the artist's presence, as would later become characteristic of his work (fig. 12).

Figure 12_ Gordon Matta-Clark, Rope Bridge, Six Mile Creek, Ithaca, New York, 1968. Source: © The Estate of Gordon Matta-Clark / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Courtesy of The Estate of Gordon Matta-Clark and David Zwirner.

For the sophisticated performance piece Tree Dance, staged on May 1, 1971, for the exhibition Twenty-Six by Twenty-Six, Matta-Clark climbed to the top of a large oak tree next to the Vassar College Art Gallery in Poughkeepsie, New York. Using a system of ropes and ladders, he created a habitable space in the form of a cocoon made from nylon parachutes suspended from the branches (Moure 2006, 90). The action was filmed in Super 8, in black and white, and without sound. The 9-minute, 32-second film showed his collaborators adjusting the ropes, the structure being raised and lowered, its playful swinging motion, and the ways in which the space was occupied. With its gravity-defying, acrobatic quality and its conceptual exploration of the biological and metamorphic meanings of "refuge," this arboreal dance evoked the lightness of habitat in contrast to the heaviness of architectural construction (fig. 13).

Figure 13_ Gordon Matta-Clark, Tree Dance, 1971. Source: © The Estate of Gordon Matta-Clark / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Courtesy of The Estate of Gordon Matta-Clark and David Zwirner.

Broadly speaking, dance can be discerned as an element in all three of these outdoor works—whether associated with a bridge, a tree, or a ladder. Dance indeed played a significant role in Matta-Clark's artistic formation: he maintained close relationships with dancers such as Carol Gooden, collaborated on various performance pieces with theater directors like Bob Wilson, and was acquainted with many leading figures in the dance world of the time.

New York's countercultural scene of the 1960s and early 1970s was marked by a proliferation of new theatrical forms, including new dance and the happening. Rooted in performative practices that engaged the body, space, and the mundane, these events were characterized by improvisation and an indeterminacy of temporal and spatial relationships.

John Cage, a pioneer in challenging traditional artistic conventionalisms, brought this spirit into the world of dance by exploring the potential of everyday bodily movements. His collaboration with Merce Cunningham at Black Mountain College in the summer of 1952 would influence subsequent generations of dancers, some of whom also trained with Anna Halprin, including Simone Forti, Trisha Brown, and Yvonne Rainer. Rainer, in particular, became one of the most significant figures in this new, unconventional form of dance through her work with the Judson Dance Theater, which, between 1962 and 1964, served as the epicenter of new dance in New York—championing the mundane and embracing movement within repetitive structures (Pineda Pérez 2006, 29).

With these precedents in mind, one can begin to understand the context of the transdisciplinary scene in New York's SoHo during the 1960s. It was here that Matta-Clark developed close ties and creative affinities with artists such as Robert Rauschenberg, Richard Nonas, Dennis Oppenheim, and others associated with 112 Green Street, founded in 1970 by Jeffrey Lew, Alan Saret, and Gordon Matta-Clark himself. This was a space where choreographers, dancers, and visual artists could meet in an interactive environment to exchange ideas on corporeal and visual practices. Other participants included Trisha Brown, Deborah Hay, and the collective Grand Union.

It should be noted that the three dance-related works by Matta-Clark mentioned thus far all involved an element of risk in their construction and inhabitable space, comparable to a high-wire act. The theatrical tension inherent in tight-rope performance was something Matta-Clark would also employ in Clockshower (1973), in which he suspended himself from the top of a clock tower in downtown Manhattan to carry out a series of prosaic actions.

A sense of danger and vertigo is likewise present in Matta-Clark's "cuttings" of abandoned buildings—the interventions for which he is best known—through which he generated exhilarating new experiences of space. In any case, there is little difference between photographs showing the intrepid and often precarious positions assumed in his performance pieces and those depicting him wielding an electric chainsaw, bent over a handsaw, crouching with a blowtorch, hanging from a building façade, climbing through a hole in a roof, or peering through one of his newly-made openings. The same daredevil attitude evident in his rope bridge performance and his ascent into trees or up rope ladders is equally present in his traversal of architectural voids, such as those cut into the floor slabs of abandoned buildings (fig. 14).

Figure 14_ Gordon Matta-Clark, Bronx Floor: Threshole, 1972. Source: © The Estate of Gordon Matta-Clark / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Courtesy of The Estate of Gordon Matta-Clark and David Zwirner.

The spatial and corporeal experiments seen on a grand scale in Jacob's Ladder have their origins in the initial stage of Matta-Clark's training in land art, during which he assisted artists such as Dennis Oppenheim, Robert Smithson, and Christo in their earthworks. From Christo in particular, he learned a great deal about the pre-planning required for such projects.6 These works can also be understood as complementary experiments in the modification of space, in continuity with his own explorations of perception and materiality through the opening of space by dissection. With these elements and others, Matta-Clark was, in effect, producing architecture in transformation.

With Jacob's Ladder, Matta-Clark pushed boundaries and generated a dynamic space that defied gravity. It was not a performance to be contemplated, but rather a "happening"— the result of a peripheral action that incorporated both the specificity of place and the documentation of process. The installation thus became an invitation to perceive space in a new way. Perhaps more than any of his other works, Jacob's Ladder embodied his understanding of architecture and space—a vision closely aligned with that of Constant and Yona Friedman, directly related to his cuttings, and far more profound than it might initially appear.

With his cuttings, understood as spatial performances, Matta-Clark was fundamentally transforming space: the established units of perception were altered, and the barriers that deny possibilities of entry, passage, and participation were dismantled. New spaces in movement were thereby generated, rich in meaning and vision, at a time when the disciplinary codes of conventional architecture were being deciphered and boldly challenged. In the words of Richard Nonas, "It's not a critique in architectural terms, it's a critique of architectural terms" (Wigley 2018, 483).

In the cases presented here, Picasso captured space through the movement of his body, Pollock painted with his body across the space of his canvases, and Duchamp moved his own body through space. To a certain extent, all three were forerunners of what would become performance art. Meanwhile, Matta-Clark transformed architecture into "something different from a static object, into a verb, an action" (Matta-Clark 2020, 54). He effectively reformulated the concept of space, penetrating the inner workings of architecture as Picasso had penetrated space by drawing with light, as Pollock had by painting from all sides of his canvas, and as Duchamp had by descending his staircase—just as Matta-Clark would do by climbing to the top of his vertiginous ladder.

1 Shortly before their publication in ArtNews in 1951, thirty of the photographs also appeared in the third and final issue of Portfolio magazine. This limited-edition journal of graphic design was assembled under the artistic direction of Alexey Brodovitch, with whom Namuth had trained, and who was also responsible for the art direction of Harper's Bazaar.

2 From this moment on, ArtNews, under the direction of Thomas B. Hess, became interested in visiting artists in their studios to document their methods of creating pictorial or sculptural work. The article on Pollock was followed by one on Willem de Kooning.

3 The technique of photodynamism made it possible to depict different moments in time, incorporating photomontage, double exposure, optical distortion, and aerial photography. This enabled the transition from still photography to the decomposition of movement and helped prepare the ground for chronophotography.

4 Matta-Clark was Duchamp's godson, and the two often played chess together in Manhattan's Greenwich Village.

5 The transfer of the Matta-Clark archive to the Canadian Centre for Architecture in Montreal by Jane Crawford and Anne Clark—the artist's wife and mother, respectively—marked a shift in the archive's interpretive framing from the artistic field toward architecture.

6 In 1969, Matta-Clark assisted Dennis Oppenheim with the Beebe Lake project for the exhibition Earth Art, organized by Cornell University in Ithaca, NY. In 1971, he helped Christo create scale models for the Valley Curtains project, done in collaboration with Jeanne-Claude in Rifle, Colorado in 1972. Following this collaboration, he produced his own version—often referred to as Curtain simulation for Christo or Belly Curtain: an Homage to Christo's Valley Curtain—using his own body. In photographs taken by producer Harold Berg, he appears nude, stretching fabric between his thumb and index finger, between his legs, and between his shoulder and knee, as well as holding a piece of cloth together with a nude female companion.