How to Cite: Olmedo Latoja, Paula Andrea. "From Body to Space: Kinesthetic Transitions of the Architectural Artifacts Choreographic Labyrinth and Exicosahedron". Dearq 44 (2026): 30-41. https://doi.org/10.18389/dearq44.2026.04

How to Cite: Olmedo Latoja, Paula Andrea. "From Body to Space: Kinesthetic Transitions of the Architectural Artifacts Choreographic Labyrinth and Exicosahedron". Dearq 44 (2026): 30-41. https://doi.org/10.18389/dearq44.2026.04

Paula Andrea Olmedo Latoja

Universidad de Sevilla, Spain

Received: December 2, 2024 | Accepted: July 14, 2025

This article presents a research-creation process that explores the intersection of architecture and contemporary dance through the architectural artifacts Choreographic Labyrinth and Exicosahedron, placing kinesthetic experience as its core. This perspective engages both the tangible and intangible dimensions of design, with the body serving as the primary medium of exploration and formal expression. Grounded in a conceptual framework and an experimental methodology—including drawing, choreography, model-making, and performative instruments—the geometries and materialization of the artifacts are analyzed, composed, constructed, and interpreted as an interactive, temporary architecture that fosters bodily and spatial awareness.

Keywords: Bodily space, kinesthetic experience, temporary architecture, architectural clothing, performative design, choreography.

This article forms part of an early-stage, design-oriented doctoral research project that examines the relationship between the human body and space, taking movement as one of the most evocative means of deepening this connection. The project begins with the body—conceived as a primary space—and extends toward the creation of architectural artifacts that, through their configurations, express the singularities of the relationship between corporeality, spatiality, and movement.

The proposal builds on the research project "The Choreographic Labyrinth Play Module: Kinesthetic Experience for Cognitive-Motor Stimulation in Early Childhood" (Olmedo Latoja 2022), whose conceptual foundations have catalyzed new processes of inquiry and creation. This work emerges from a transdisciplinary collaboration between an architect-dancer, an architect, and a choreographer, who, through the dialogue between architecture and contemporary dance, explore how bodies in motion both configure and are configured by space. In this way, the body transcends its role as an object of analysis and positions itself as an active subject in spatial design.

The project is grounded in the concept of kinesthetic experience, understood as the perception and awareness of one's own body and its relation to space while in motion (Gálvez 2019, 35). Within this framework, choreography and movement practices are proposed as both methodological and creative tools for revealing and designing spatial dynamics. This approach establishes a foundation for conceiving architecture that engages in direct dialogue with the body in action.

To implement these approaches, we present the development of the Choreographic Labyrinth and the Exicosahedron, conceived as architectural artifacts that, through their formal and material characteristics, encourage both movement and reflection. They focus on the subject who inhabits and/or manipulates them, foregrounding the relationship between the spatiality of the body and the corporeality of space.

From the Vitruvian Man to the Renaissance, the human body occupied a central place in architectural theory, serving both as a model of proportion and as a unit of measurement. In modernity, however, Cartesian logic reduced the body to a static and standardized object, as reflected in the canons of Ernst Neufert, Le Corbusier, and Henry Dreyfuss. These frameworks neglect the complexity of bodily experience and reinforce exclusionary norms (Ferreira 2015; Gálvez 2021).

In turn, architectural training has traditionally been tied to vision, relegating the other senses to a secondary role. Although digital tools have broadened the design repertoire, these "extensions of the eye" (Pallasmaa 2014, 30-34) continue to subordinate tactile and sensory perception, distancing design from a more comprehensive understanding of the environment.

In response to these paradigms, new approaches have emerged that advocate for a more comprehensive understanding of space. Merleau-Ponty (2002) argues that space is not neutral but is constituted through action, perception, and experience. Lefebvre (2013) defines space as something that takes shape through the act of being inhabited, while Sarah Robinson (2021) conceives it as an envelope extended from bodily and perceptual systems, conditioned by the emotional and somatic state of each subject.

In this context, it becomes necessary to rethink the role of the body in architecture. Is it possible to design from the experiential body, rather than from the body-diagram? Human existence is fundamentally sensory and corporeal. From a phenomenological perspective, Johnson (1991) defines embodiment as the occupation of space through the body itself. Along similar lines, Sheets-Johnstone (2011) argues that movement is a primary source of knowledge and perception, as it constitutes a meaningful experience unfolding in the present. Her notion of the conscious body refers to a body that reflects in movement, where meaning emerges and guides action.

As Johnson (1991) observes, spatial concepts such as containment, balance, or force are first experienced physically. In this sense, embodiment can also be understood as an architectural phenomenon, where the body is recognized as a central agent in design and lived experience is given priority.

In short, the body is no longer a layer or a mere object; it is a situated and extended organism, nested within the space it occupies and envelops (Gálvez 2019, 121). The relationship between body and space is thus revealed through movement: the body discovers the world by moving through it. Choreographer Marina Mascarell (2021, 8) captures this as "the implication of being a body," condensing into this definition an ontological condition and its consequence: the body unfolds all its dimensions only in and through movement.

From this perspective, contemporary dance—as an ephemeral artistic expression situated in a specific time and space—offers a vital point of reference. The transdisciplinary approach that interweaves architecture and dance makes it possible to articulate diverse concerns around related issues. This engagement is not only intellectual but also experiential: inter-esse—being in-between—configures a common ground where both disciplines enrich one another, fostering a critical, sensitive, and creative perspective.

For the body, moving means engaging with the world; for architectural space, welcoming movement means manifesting itself as built space. In this correlation lies the potential of contemporary dance as a research practice for architecture: it is through movement that the self and the environment encounter one another, and that the body relates both to other bodies and to space. Contemporary dance—by cultivating awareness of the body's weight, position, behavior, and interaction with its surroundings, as well as its own composition and internal organization—emerges as a means of exploring and understanding the appropriation, perception, and physical experience of space. Questioning the body as a medium of space, recognizing its capacity for knowledge, and understanding it as a tool of expression and communication open new possibilities for the architectural discipline (Martínez Sánchez 2020).

Thinking of architecture as a practice activated from and through the body implies recognizing the body not only as a measure or point of reference, but as an agent that generates space. From this perspective, three central questions arise: How can the human body be used to shape space? How can the relationship between body and space be investigated through matter? How can architectural ideas be explored through the body?

The separation between body and space—both physical and conceptual—is a historical fiction, a paradigm that conceives the body from the skin outward and space as a static, isolated entity. In reality, body and space exist in continuity (Aguilar Alejandre 2015, 22): without the body there is no perception, no space, and no architecture to perceive. We inhabit through and with the body. From this perspective, architectural space must be understood as a process, a system, a verb (Robinson 2021)—an entity that extends from our bodily structure and encompasses body, medium, and environment (Gálvez 2019).

These issues find a strong parallel in William Forsythe's1 ephemeral, kinesthetic, and playful spatial installations, which invite subjects to actively engage, adapt, shift positions and perspective, and even risk losing balance and stability. In a similar vein, the work of Laban marked a turning point in dance by placing movement—rather than static position—at the center. From this perspective, body and space emerge as interrelated counterparts, bound together through experience in movement. Two key references illustrate this convergence:

Understanding the references discussed above helps to reveal the interrelationships between body, space, and movement. In particular, attention is drawn to three key dimensions: how movement generates dynamics of tension and release, how space conditions bodily trajectories, and how the body, in turn, creates and configures spatialities.

Based on these premises, the creative process is organized around two formal conditions: the cube and the labyrinth. The cubic order is linked to Laban's (2006) conception of the Kinesphere as a spatial system containing a virtually inscribed cube, which represents the most significant directions of movement. This geometric structure synthesizes the three fundamental planes and axes of bodily movement: the frontal plane-sagittal axis, the horizontal plane-vertical axis, and the sagittal plane-frontal axis. Complementing this, the figure of the labyrinth is introduced as a device that, following Forsythe's perspective, stimulates spatial decision-making through the perception and projection of movement.

Under these conceptual premises, the formal study of architectural artifacts is pursued through kinesthetic explorations that conceive the body as an instrument that is both geometric and performative at the same time. The central objective is to activate an awareness of corporeal-spatial interaction, shifting the emphasis from the act of designing to the experience of inhabiting a temporary architecture.

In this research, doing—as a way of thinking about architecture through the body—constitutes both the strategy and the methodological principle that organizes and guides the design process during the creative phase. The methodology begins with the human body: drawing it, breaking it down, and designing from it, using techniques such as drawing, modeling, photography, video, and performance.

The exercise revisits Schlemmer's approach (Blume 2015) in the Bauhaus Dances, emphasizing the possibilities of the body as a perceptive and flexible instrument, not only as a generator of ideas, but as a central principle for exploring space. Such an embodied approach requires direct engagement with physical matter in order to investigate its corporeal, visual, spatial, and tactile properties. For this reason, the hand-scale model or mock-up is employed as the primary design method: not as a final representation or simulation, but as an active medium for triangulating body, space, and matter.

The design process is structured as an experimental methodology that engages the body, space, and architectural artifacts through an iterative and collaborative dynamic. This approach integrates performative practice, spatial design, and material experimentation, unfolding as follows:

The initial stage explores thinking through the body, cultivating bodily awareness in movement—whether at rest, in motion, in isolation, or in relation to other bodies and the environment. Fundamental principles of dance—space, time, effort, and form—are explored with the aim of employing the body as a tool for thought, allowing spatial dynamics to emerge intuitively and sensorially.

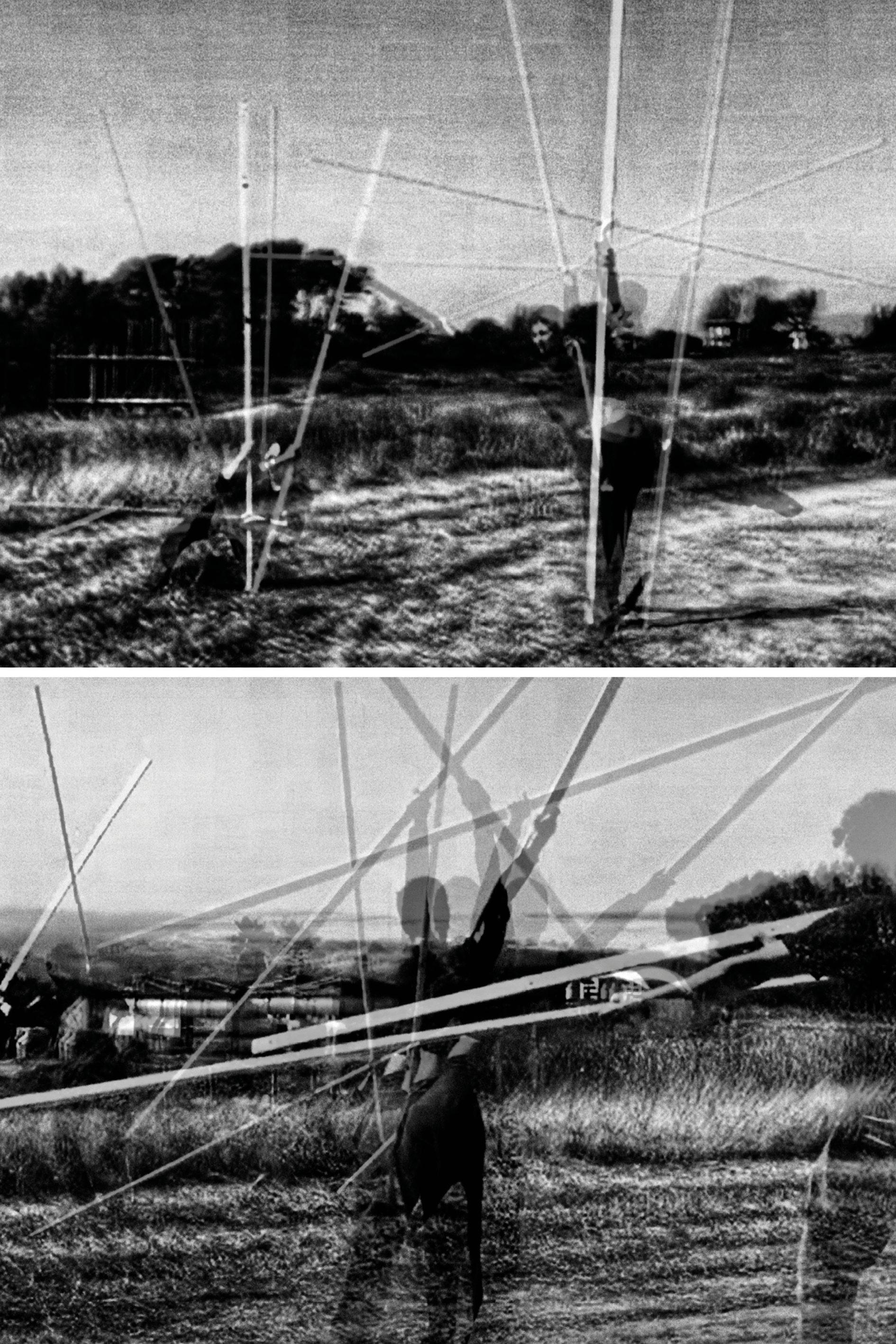

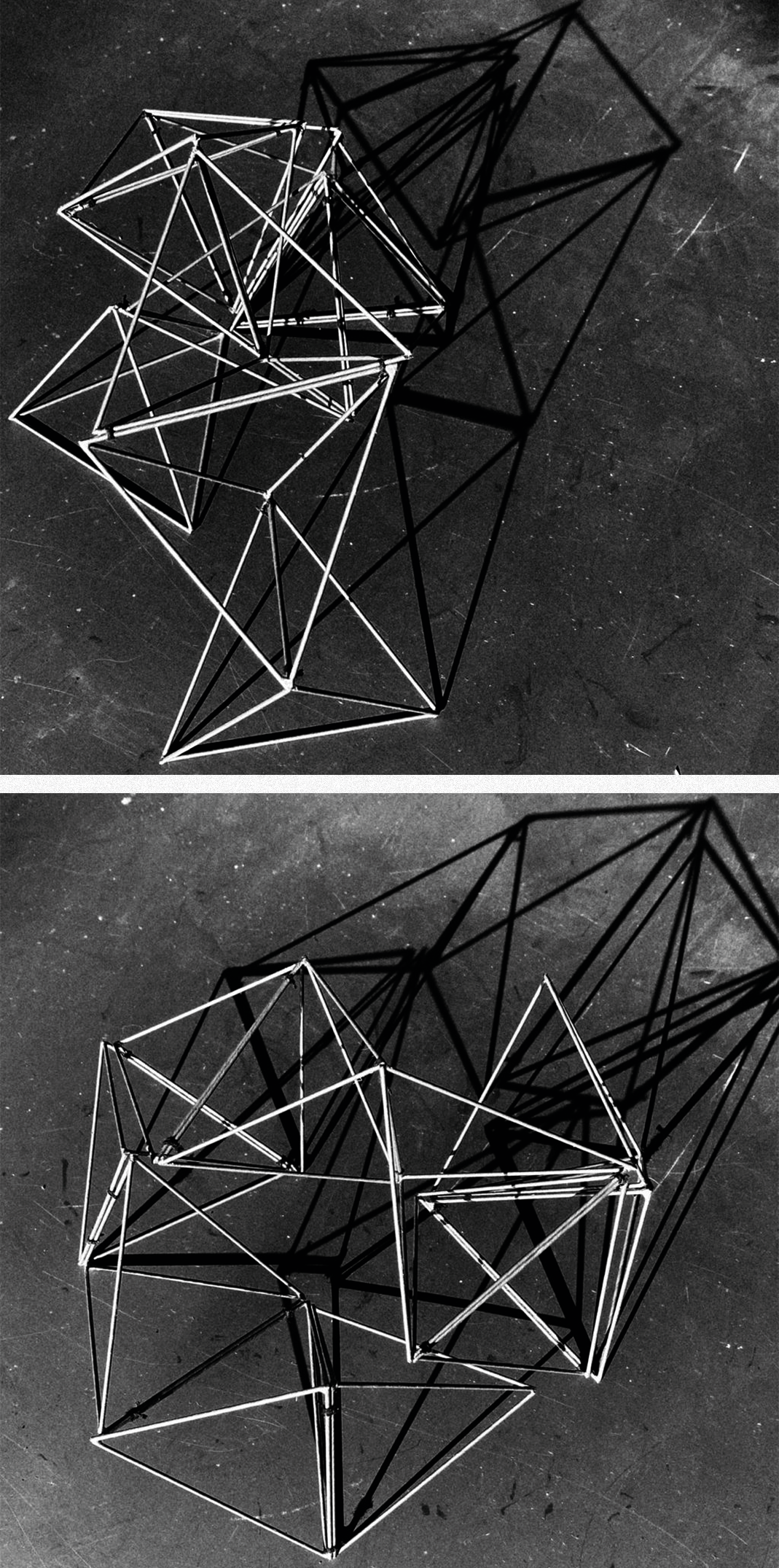

In the second stage, material elements—linear, flat, rigid, flexible—are introduced to amplify the body's capabilities in motion. Pinewood slats (fig. 1) and PVC pipes (fig. 2) function as extensions and supports that intensify the body's interaction with space, serving as instruments to explore its possibilities, limitations, constructive logic, and compositional patterns.

Figure 1_ Movement sequence in which wooden slats are used as rigid extensions of the bodies. (2023). Source: Photograph by the author.

Figure 2_ Movement practice using PVC pipes as articulated extensions of the body. (2023). Source: Photograph by the author.

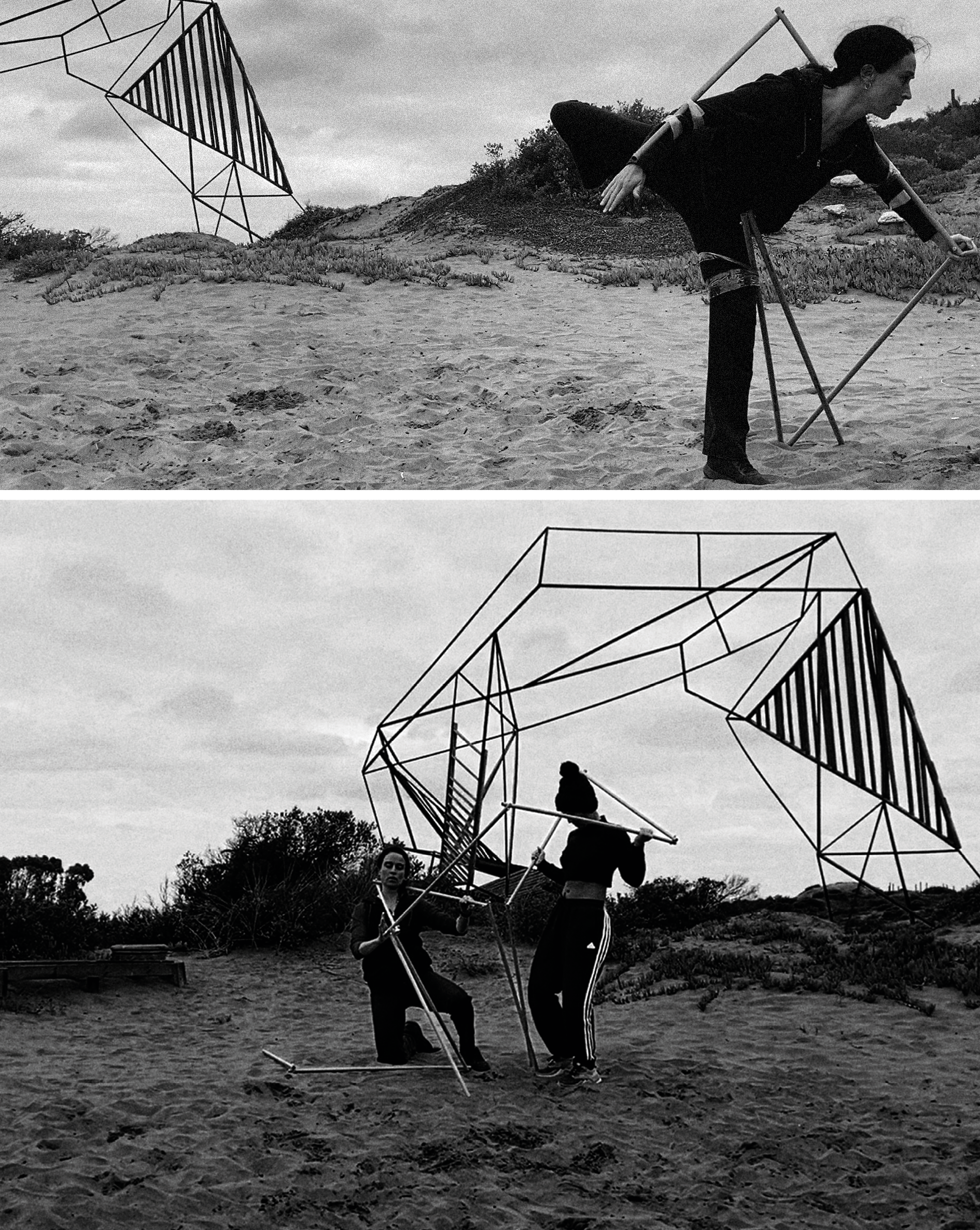

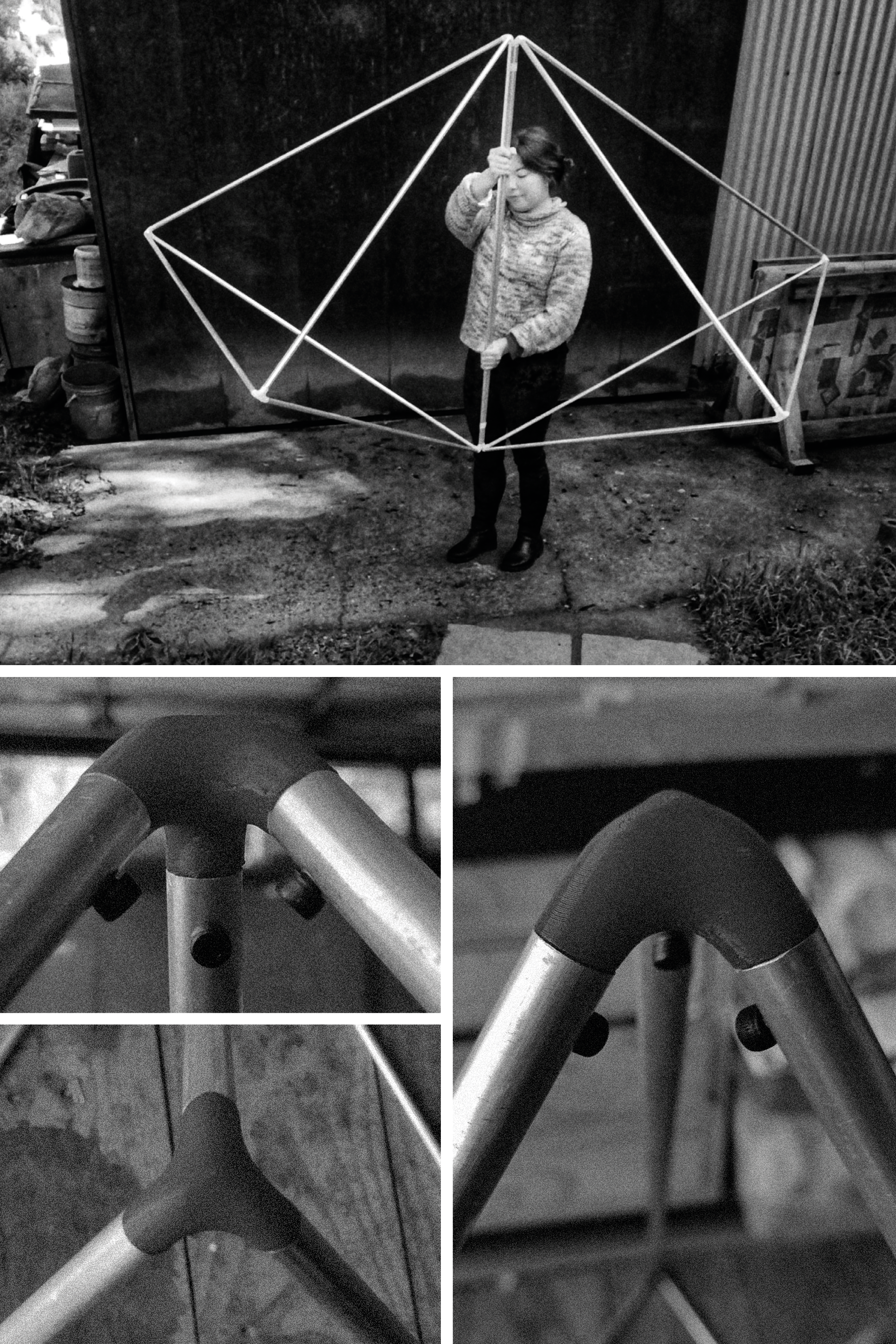

In order to observe and record the geometric configurations of the body in motion tangibly and in real time, an interactive device called Exicosahedron (fig. 3) was conceptualized and prototyped. This structure, composed of six articulated bamboo pyramids, represents a fragment of a regular icosahedron that transforms in response to the movements of the person manipulating it.

Figure 3_ Two bodies experience the concept of tension through the Exicosahedron device. (2023). Source: Photograph by the author.

The documentation of this phase includes photographic records that break down and capture sequences of movement, enabling subsequent analysis of the body's geometries and trajectories under different physical conditions—generic, situated, and decontextualized.

During this phase, the movements that form an initial choreography are selected, rehearsed, and defined. Attention is directed toward bodily actions and their contextual relationships. The process is repeated multiple times under varying conditions and with different numbers of bodies on stage, allowing the choreography to adapt to its environment and revealing how that environment influences the types of movement generated.

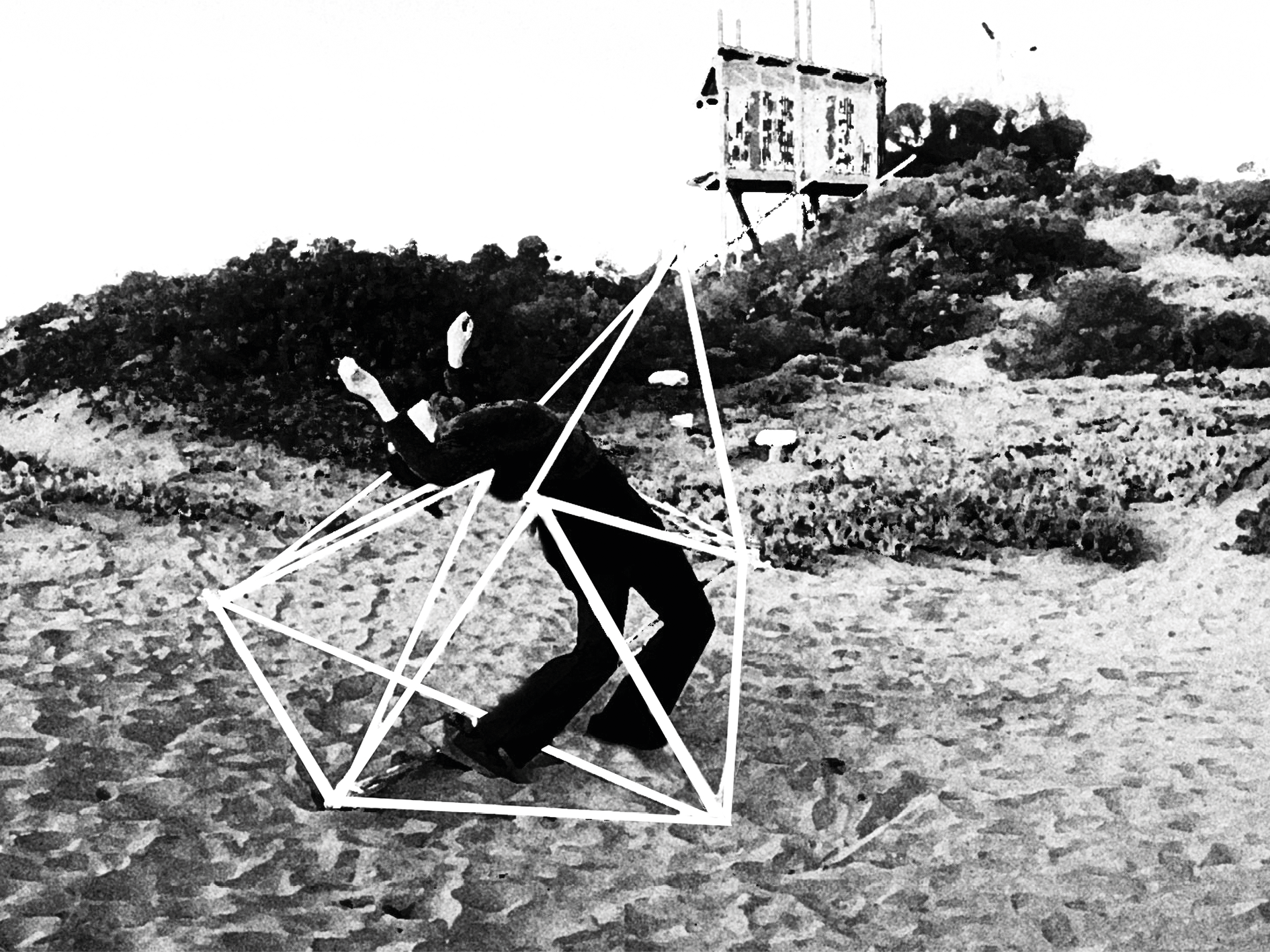

Based on the material collected, the analysis begins with geometry as a tool for abstraction and composition. Specific movements are selected that embody non-everyday bodily positions, which are then abstracted into geometric patterns through analog and digital drawing. The aim is to blur the figure of the body in order to explore fundamental elements such as axes, directions, extensions, and articulations between bodies and surfaces. The key points of each bodily gesture are fixed and connected by lines, generating polyhedra that synthesize bodily tensions (fig. 4).

Figure 4_ Geometric drawing exercise designed to discover different body conditions and analyze similarities or variations between them. (2023). Source: Digital illustration and photograph by the author.

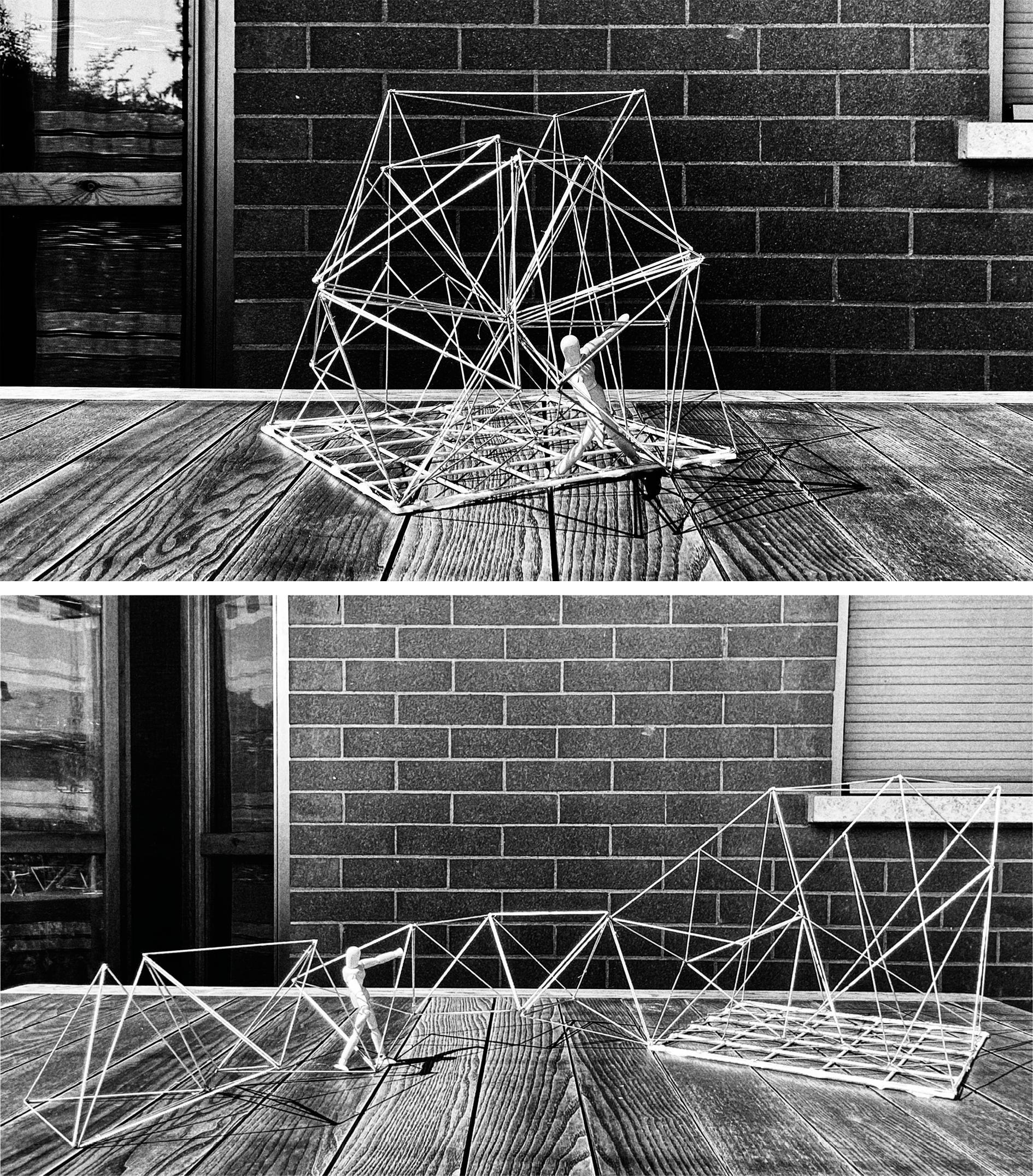

The synthesis phase focuses on the design, prototyping, and manufacture of a spatial artifact. The process begins with the translation of two-dimensional lines into three-dimensional structures, using metal wire to draw geometry in space and materialize volumes. From these wire frameworks, the body is reintroduced through a scale articulated mannequin, which enables the simulation of variables such as movement, scale, materiality, and constructive logic (fig 5).

Figure 5_ Model for experimenting with the geometries that configure the spatiality of the Choreographic Labyrinth. Scale 1:10. (2023). Source: Photograph by the author.

This 1:10 scale model makes it possible to test concepts such as system, modularity, articulation, and transformation (fig. 6). On this basis, a strategy is defined to develop the structure at a 1:1 scale, generating an architectural artifact conceived at the scale of the body.

Figure 6_ Experimental model of the joints and construction logic of the Exicosahedron. Scale 1:10. (2023). Source: Photograph by the author.

In collaboration with the industrial designers at INAS Diseño, the design of the Exicosahedron device was redefined, now consisting of eight linked and articulated pyramids. Development focused on the design and prototyping of vertex pieces using 3D printing, as well as on the specification of final materials—such as aluminum and polyurethane resin—with the goal of ensuring a lightweight and manipulable artifact (fig. 7). The resulting structure was assembled at full scale, validating both its functionality and its performative potential.

Figure 7_ Prototype of the Exicosahedron device. (2023). Source: Photograph by the author.

The exploration progresses from mapping bodily movement to the situated construction of full-scale artifacts. This process involves tracing the invisible, creating volumes with wire, prototyping systems, erecting artifacts in context one by one, and performing with the body.

This is a progressive and sequential development, in which the relationship between stages does not function as a literal translation but instead configures a flexible methodology—open to interpretation and iteration. Performance plays a fundamental role throughout the process: it is not conceived as an end result or final objective, but as a design tool that informs, validates, and challenges project strategies.

The temporary architecture Choreographic Labyrinth (fig. 8)— installed for six months outside the Valparaíso Cultural Park Library and currently located in the garden of the Lord Cochrane Neighborhood Residents Committee headquarters in Viña del Mar—materializes a kinesthetic experience through a spatial configuration that integrates three components: the supporting structure, the framework, and the Exicosahedron device.

Figure 8_ The Choreographic Labyrinth at the Valparaíso Cultural Park, Chile. (2024). Source: Photograph by the author.

The supporting structure2 defines an irregular geometric body inscribed within a 3 × 3 × 3-meter cube, articulated by a virtual grid of 60 × 60 cm squares. This dimensional modulation arises from a systematic bodily exploration that establishes the maximum interstice of passage for the body in motion.

The framework3 introduces rigid inclined elements that deviate from the vertical axis, creating spatial interstices that challenge perceptions of balance and encourage multidirectional bodily navigation. Its design incorporates three levels of movement—upright, folded, and quadrupedal—configuring a system that invites active and experimental interaction with the space.

The Exicosahedron4 device is conceived as a fragment of an icosahedron, broken down into eight interconnected pyramids and designed for both individual and collective manipulation. It functions as a translator of movement, converting bodily actions into tangible spatial configurations and fostering a continuous dialogue between corporeality and spatiality.

The Choreographic Labyrinth is conceived as a temporary architecture designed to foster a multidirectional dialogue between bodies and the space that contains them. The installation reveals cavities that suggest passages, lines that indicate supports, and repositories that invite reflection. The proposal allows us to observe the possibilities of activation between bodies with diverse movement experiences, cultivating an expanded sensitivity to inhabiting one's own body and its context.

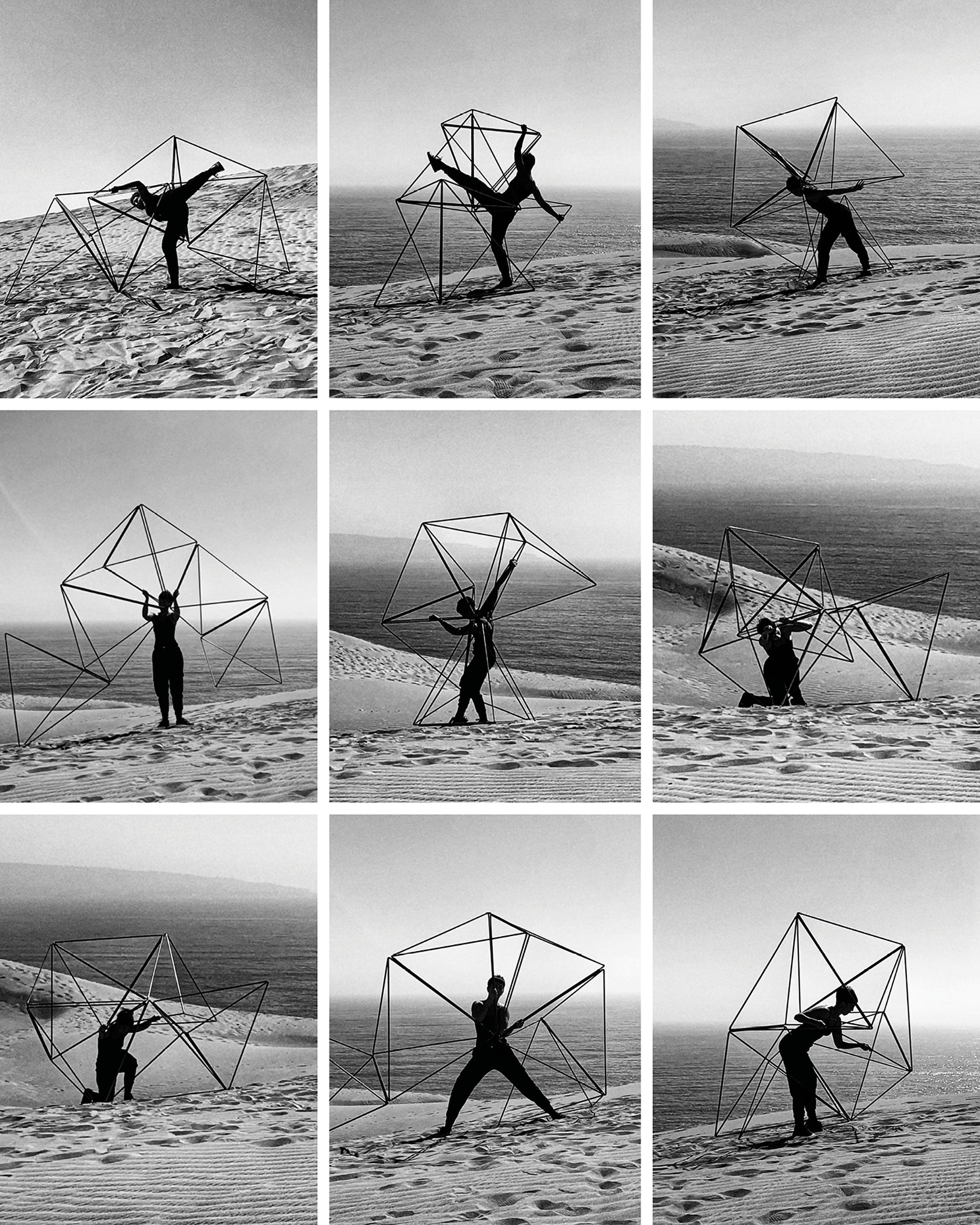

Both in the interaction with the static structure—where movement emerges through evasion of or adherence to its geometry (figs. 9 to 12)—and in the manipulation of the Exicosahedron—which generates new spatial configurations (figs. 13 to 16)—the project fosters an expanded bodily experience.

Figures 9 and 10_ Bodies experiencing the spatiality of the Choreographic Labyrinth at the Valparaíso Cultural Park. (2024). Source: Photograph by the author.

Figures 11 and 12_ Choreography recording in the Choreographic Labyrinth at the Lord Cochrane Neighborhood Residents Committee headquarters. (2025). Source: Photograph by the author.

Figures 13 to 15_ Bodies exploring corporeal-spatial configurations with the Exicosahedron. (2024). Source: Photographs by the author.

Figure 16_ QR code linking to audiovisual records of the Choreographic Labyrinth and Exicosahedron. (2024). Source: Records by the author.

This proposal arises from a critical observation: technological advances and digitalization have encouraged increasingly sedentary practices, narrowing the repertoire of human movements and distancing architecture from direct bodily experience. In response, the study of architecture through the body is proposed, exploring its potential as a performative discipline, a bodily practice, and a methodological process.

The research is organized around three axes: the configuration of space through the articulation of movement and matter; the architectural process understood as an embodied, iterative, and generative method; and a non-linear methodology grounded in interconnected exercises that foster progressive and critical learning. From a laboratory perspective, both conceptual and material experiments are developed, involving the body as an active medium of thought and creation.

The method guides exploration from observation to representation and experimentation, integrating tools such as performance, tactile modeling, body mapping, and prototyping. These practices generate both a collection of experimental artifacts and a matrix of transferable architectural strategies. The Choreographic Labyrinth and the Exicosahedron embody this vision, placing movement and bodily experience at the core of architectural thinking. These artifacts propose a tangible interaction between body and environment, underscoring that architecture—rather than a purely technological product—is a fundamentally human creation, whose essence must integrate corporeality as its generative principle.

The project challenges the conception of architecture as a static entity, proposing instead an interactive medium that establishes a dialogical relationship with the body. From this perspective, architecture not only accommodates movement but also operates as an information system that, through its geometry and structure, stimulates new forms of bodily interaction.

The installation seeks to elicit phenomenological reflection, inviting awareness of how objects and spaces engage us through their geometry, structure, and perceptual qualities. Concepts such as articulation, materiality, surface, choreography, and place manifest as direct, transformable bodily experiences.

This approach entails a fundamental shift from space as a passive object of contemplation to space as an active field of experimentation, where body and environment continuously co-create one another in a reciprocal process of discovery.

This exploration highlights the fundamental role of the kinesthetic sense as a mechanism for activating and defining corporeality in space. Through proprioception, the body organizes spatial information, generating a situated cognition that enables it to orient itself, recognize itself, and project itself into the environment.

The creative process demonstrated the potential of corporeal-spatial exercises and their graphic translation as methodological tools. Movement and choreographic practice functioned as generative means of articulating space, integrating layers of knowledge such as:

Experimentation with the Exicosahedron device functioned as a tangible mediator between body, space, and movement. Its articulated structure, responsive to the movements of the person manipulating it, generates multiple geometric configurations, producing what may be described as choreographic drawing in space.

The Choreographic Labyrinth is conceived as a temporary architecture that emerges in the interstice between architecture and dance. The installation proposes an essential kinesthetic experience: a call to attune once more to the body and its escape routes, a drawing of the body as it communicates with and responds to space.

Likewise, the project raises the possibility of transferring these experiences to educational, community, or therapeutic contexts, where spatial design can contribute to fostering body awareness and enhancing perception of the environment. For future implementations, the development of more systematic documentation methodologies is proposed, enabling the comparative recording and analysis of the experiences of those who inhabit the architectural artifacts.

In this sense, a future line of work will involve applying this methodology to conceive other architectural artifacts within concrete and/or specific spaces, or across different spatial scales. Both the Choreographic Labyrinth and the Exicosahedron function as self-contained structures, guided by an internal logic that does not necessarily correspond directly to the environments in which they are situated. Exploring the interaction of such artifacts with defined contexts would make it possible to observe how bodily experience is reconfigured in relation to specific spatial conditions, and how these, in turn, influence perception, movement, and the construction of meaning.

These artifacts can be understood as a form of primary architecture: spatial forms that emerge from the body and project outward into the environment. It is an architecture that celebrates the body and proposes new ways of conceiving design through what is at the same time the most evident and radical gesture: the conscious activation of the body in space.

Creation and Direction: Paula Olmedo Latoja

Collaborating Architect and Graphic Design: Matteo Lotrionte

Dance and Choreography Consultant: Francisca Silva Gazitúa

Structural Consultant: Luis Della Valle

Construction and Assembly of the Choreographic Labyrinth: Miguel Alvayay

Exicosahedron Fabrication: INAS Diseño —Valentina Muñoz, Camila Campos, and Carolina Espinoza

Collaboration in Choreographic Action: Catherine Chávez Améstica

* Project funded by the National Fund for Cultural Development and the Arts, Call for Proposals 2023, of the Ministry of Culture, Arts, and Heritage of Chile.

1 See >William Forsythe, Choreographic Objects, available at: https://www.williamforsythe.com/installations.html.

2 The supporting structure combines metal and wooden elements. The base consists of perimeter beams made of C-channel steel (100 × 150 × 3 mm) and interior beams made of planed pine wood (2" × 4"), with planed pine decking (1" × 5"). The main structural elements are round steel tubes (2"diameter, 3 mm thick), assembled using welded plates and bolts. The bracing is made of round steel tubes (1", 2 mm thick).

3 The elements are round steel tubes (5/8" in diameter and 1.5 mm thick) with flattened ends, secured with U-shackles to eye bolts anchored in the base structure and connected at the top to the supporting structure by bolt fasteners.

4 The edges of the final structure are made of aluminum tubes (1/2" in diameter, 120 cm long), modified at their ends by flattening and folding. The joining system uses Allen bolts and safety nuts, while structural flexibility is achieved through fabric hinges, allowing for geometric transformations.