How to Cite: Flores Romero, Jorge Humberto and Juan Carlos Lobato Valdespino. "Inhabiting the Scene: Body, Architecture, and Cinematic Narrative in Domestic Space". Dearq 44 (2026): 54-66. https://doi.org/10.18389/dearq44.2026.06

How to Cite: Flores Romero, Jorge Humberto and Juan Carlos Lobato Valdespino. "Inhabiting the Scene: Body, Architecture, and Cinematic Narrative in Domestic Space". Dearq 44 (2026): 54-66. https://doi.org/10.18389/dearq44.2026.06

Jorge Humberto Flores Romero

Universidad Michoacana de San Nicolás de Hidalgo, Mexico

Juan Carlos Lobato Valdespino

Universidad Michoacana de San Nicolás de Hidalgo, Mexico

Received: December 10, 2024 | Accepted: July 21, 2025

This article examines the relationship between body, architecture, and cinematic narrative in domestic space, using an interdisciplinary approach that combines bodily phenomenology, atmospheric analysis, and cinema as an interpretive tool. Through microgestural analysis and spatiotemporal cartography of the films Roma (Cuarón 2018) and Luz silenciosa (Reygadas 2007), specific bodily dynamics are identified that configure domestic territories and dwelling choreographies. The findings establish architectural design criteria grounded in the embodied experience of dwelling and propose cinematographic analysis methodologies applicable to contemporary design.

Keywords: Body, architecture, cinematic narrative, domestic space, phenomenology, architectural design, atmospheres.

The transformation of architectural space into inhabited place constitutes one of the most complex and compelling phenomena of contemporary human experience. This process transcends the mere physical occupation of space, entering an intricate web of cultural significations, personal memories, and bodily practices that fundamentally shape our relationship with the built environment. In the domestic realm, this transformation acquires particular depth and resonance, for it is precisely there that architectural materiality interweaves most intimately with the personal and collective narratives of its inhabitants.

Domestic space thus emerges as a privileged territory for understanding how architecture not only shelters but actively configures daily practices, social relations, and individual identities. Each repeated gesture, each habitual trajectory, and each domestic ritual inscribes layers of meaning in space that progressively transform the house from a neutral container into a home charged with memory and affect. This transformation occurs through what may be described as a choreography of dwelling, in which bodies in movement continuously inscribe the meaning of space through their daily practices.

The dialogue between cinema and architecture has evolved significantly from Sergei Eisenstein's pioneering work on cinematic montage and spatial composition, giving rise to a robust field of research that explores the multiple dimensions of this relationship. Vidler (2000, 99) marks a turning point with his analysis of the explosion of space when he argues that "the architecture of film has acted, from the beginning of this century, as a laboratory, so to speak, for the exploration of the built world—of architecture and the city," thereby establishing that both disciplines share a common concern for the construction of subjective spatial experience, linking spatial perception and emotional experience in an indissoluble way. This perspective is methodologically expanded by Penz (2017, 112), who develops specific analytical tools, arguing that "cinema offers an understanding of inhabited space that goes beyond the two-dimensional representation of traditional architectural plans."

In the urban context, Koeck (2013, 67) extends this vision by proposing that "the cinematic city is not merely a representation of the real city, but an autonomous construction that actively influences our perception of urban space." Graham Cairns (2013, 89) complements this perspective by elaborating on how "architectural spaces in cinema are not mere containers of action, but active agents in the construction of narrative meaning," thus establishing a fundamental bridge between spatial materiality and the construction of meaning.

Recent developments have refined these approaches toward more specific phenomenological aspects. Vahdat and Kerestes (2023, 5) explore the innovative concept of spatio-cinematic betwixt as a territory formed by the "liminal space between architecture and film—through existential experience," where architectural and cinematic experience intertwine in a phenomenologically indistinguishable way, becoming a space of transdisciplinary exploration that transcends conventional boundaries between media. This phenomenological perspective is further developed by Alonso-García et al., Rincón-Borrego, and Pérez-Barreiro (2023, 91), who analyze how cinematic images "not only document architectural space, but actively participate in its phenomenological construction," thus establishing the foundations for a more integral understanding of the relationship between cinema and architecture.

However, despite these significant advances, a notable gap persists in the study of domestic space from a bodily and phenomenological perspective applied directly to contemporary architectural design. Existing works have focused predominantly on urban or monumental spaces, leaving the intimate dimension of dwelling relatively unexplored as a field of architectural-cinematic analysis.

This research proposes the development of an innovative methodology of cinematic analysis applicable to architectural design, aimed at revealing the bodily and atmospheric dynamics that configure the experience of domestic dwelling. The specific objectives include: first, identifying and categorizing bodily territories and domestic choreographies as fundamental operative concepts for architectural design; second, establishing rigorous criteria for microgestural analysis and spatio-temporal cartography applicable to the cinematic study of inhabited space; and third, formulating concrete principles of architectural design grounded in the embodied experience of dwelling.

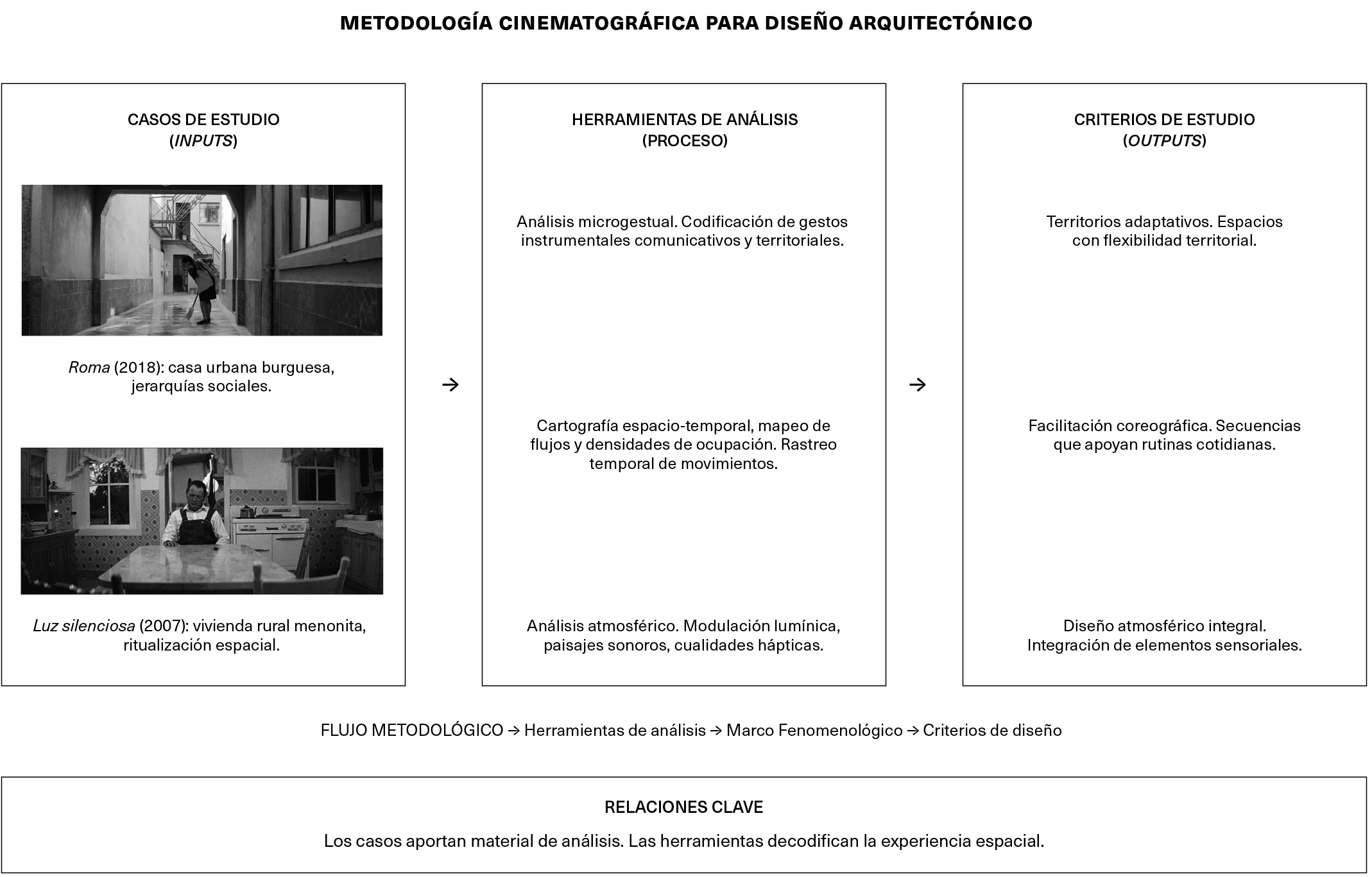

The selection of Roma (Cuarón 2018) and Luz silenciosa (Reygadas 2007) as case studies responds to precise methodological criteria. Both films offer significant typological diversity: the bourgeois urban house in Mexico City in Roma markedly contrasts with the Mennonite rural dwelling in Chihuahua in Luz silenciosa. They also present radically different cinematic treatments: Cuarón's dynamic sequence shots provide a fluid record of bodily movement in space, while Reygadas's prolonged static compositions allow contemplative observation of the ritualized choreographies of dwelling (fig. 1).

Understanding domestic space as an embodied phenomenon requires a conceptual framework that integrally articulates the bodily, temporal, and atmospheric dimensions of dwelling. A fundamental point of departure is found in Maurice Merleau-Ponty's (1993, 162) bodily phenomenology, in which he poetically establishes that "the body is in space like the heart is in the body." This organic metaphor transcends simple physical location, proposing instead a radical understanding of space as a vital extension of our corporeality.

The concept of the body schema developed by Merleau-Ponty—understood as "a global awareness of my posture in the intersensory world" (1993, 117)—is fundamental to the analysis of domestic space. This schema is not an abstract mental representation, but a way of being-in-the-world that integrates perception, movement, and signification in an indivisible unity. In the domestic context, the body schema manifests in the capacity to move in darkness, to reach objects without looking at them, and to feel the house as an extension of our own body.

This phenomenological perspective finds its operative complement in the bodily techniques described by Marcel Mauss (1936, 5), defined as "the ways in which men, society by society, in a traditional manner, know how to use their body." The relevance of this concept for domestic space lies in how these techniques configure what might be described as a true "cultural choreography of dwelling." Daily gestures—from culturally specific ways of sitting to morning cleaning rituals—are not merely functional but profoundly significant, spatially structuring social and affective relations.

The transition from the individual body toward collective practices is articulated through Michel de Certeau's (2000, 129) concept of spatial practices, in which he argues with precision that "space is a practiced place." This fundamental distinction between place as a static configuration and space as place animated by use is crucial for understanding how daily practices transform abstract architecture into lived space. De Certeau further establishes that "the act of walking is in relation to the city as enunciation is in relation to language" (2000, 109), suggesting that spatial practices function as a bodily language that continuously rewrites the meaning of domestic spaces.

A phenomenological understanding of domestic space would remain incomplete without considering its intrinsic temporal dimension. Bernard Tschumi (1994, 89) introduces this fundamental perspective by noting that "architecture is as much about space as about the event that takes place in that space." This vision introduces a dynamic understanding in which daily events do not simply occur in space but actively constitute it, continuously transforming it through repetition and variation.

Tschumi's concept of disjunction—the productive tension between architecture's formal stability and the fluidity of events—is particularly relevant to domestic space. Here, the daily repetition of routines generates both stability through predictability and ongoing change through the small variations that introduce novelty. This dialectic between permanence and change fundamentally configures the temporal experience of domestic dwelling.

The temporality of dwelling is further enriched by Kevin Lynch's (1975, 65) notion of time collage, in which he observes with insight that "place is saturated with time, time not only of the clock or calendar, but time as felt quality, as accumulated experience." In the domestic context, this temporal multiplicity manifests palpably in the superimposition of different strata: the cyclical time of daily routines, the linear time of aging materials and inhabitants, the mythic time of family memories, and the seasonal time that transforms the experience of spaces.

The integration of the bodily and temporal dimensions of space finds its most complete synthesis in Gernot Böhme's (1995, 22) concept of atmosphere, which he defines as "a co-production between the qualities of the environment (light, color, sound, materials) and the bodily and affective presence of the subject." This understanding of atmosphere as an intermediate phenomenon—neither purely objective nor completely subjective—is fundamental for understanding how domestic space is experienced primarily on an emotional level before being understood rationally.

Atmospheres, notes Böhme (1995, 26), are "diffuse, enveloping, and perceived emotionally before cognitively." This pre-reflexive quality makes atmospheres the primary medium through which we inhabit space, configuring our mood and bodily disposition prior to any conscious analysis. In domestic space, atmospheres create the affective conditions that make possible the feeling of home: warmth, security, and intimacy.

Peter Zumthor (2006, 11) translates this atmospheric understanding to the practical architectural realm by describing atmosphere as "that singular density that I perceive in each good work of architecture, that moves me." For Zumthor, the conscious creation of architectural atmospheres requires meticulous attention to materiality: "materials sound and resound: we hear the rain hitting the roof, the creaking of wood" (2006, 29). This material sensitivity connects directly with Juhani Pallasmaa's (2016, 69) fundamental critique of visual hegemony in modern architecture, in which he urgently proposes recovering the "wisdom of the body," arguing that "the body knows and remembers. Architectural memory resides in our muscles and bones as much as in our nervous system."

Cinema emerges as a privileged tool for architectural analysis precisely because of its intrinsic capacity to capture spatial experience in all its temporal and sensory complexity. Giuliana Bruno (2002, 15) conceptualizes this capacity through her notion of the emotional atlas, describing cinema as a practice that establishes "a cultural cartography that intimately connects place and psyche, site and sight, architecture and interior life."

This emotional cartography transcends mere visual representation to constitute what Bruno calls an architecture of transit: "cinema, like architecture, is an art of spatial sequences: it frames space and constructs passages that connect different spaces and inhabitants" (2002, 56). The etymological and conceptual connection between movement and emotion (motion and emotion) that Bruno establishes is fundamental for understanding how cinema simultaneously documents the material and affective dimensions of dwelling.

This understanding of cinema as embodied experience is deepened by Vivian Sobchack (2004, 38) through her concept of carnal thoughts, through which she establishes that "cinematic experience is both a form of consciousness that constitutes the world and a form of being bodily in the already constituted world." The radicalism of Sobchack's proposal lies in her affirmation that "we see and understand cinematically through our lived bodies and not merely through our disembodied eyes or intellects" (2004, 63). This perspective establishes a fundamental correspondence between the bodily experience of architectural space and the somatic experience of cinema.

The developed microgestural analysis is grounded in the sensory ethnography proposed by Sarah Pink (2009, 40), who understands "experience, perception, knowledge, and practice as something we do with our whole body and not only with our minds." This methodological approach is particularly appropriate for the cinematic analysis of domestic space, as it allows for the identification of how the bodily techniques theorized by Mauss (1936) materialize in specific gestures that reveal culturally coded ways of dwelling.

Figure 1_ Summary diagram of the proposed methodology. The methodological flow connecting the film case studies (Roma and Luz Silenciosa) with the analytical tools developed (microgestural analysis, spatiotemporal mapping, and atmospheric analysis) is outlined, from which applicable architectural design criteria are derived (adaptive territories, choreographic facilitation, and comprehensive atmospheric design). Source: the authors.

Sequences were identified in which the interaction between bodies and domestic spaces was phenomenologically significant. In Roma, the following were selected: the patio cleaning sequence (mins. 4-7), in which Cleo executes repetitive movements that reveal her subordinate relationship to space; breakfast preparation (mins. 18-24), showing the differentiated choreography between service and family; the family gathering in front of the television (mins. 29-34), evidencing spatial hierarchies; laundry washing on the rooftop (mins. 35-42), revealing segregated work territories; and the family meal (mins. 47-53), in which positions at the table materialize social relations.

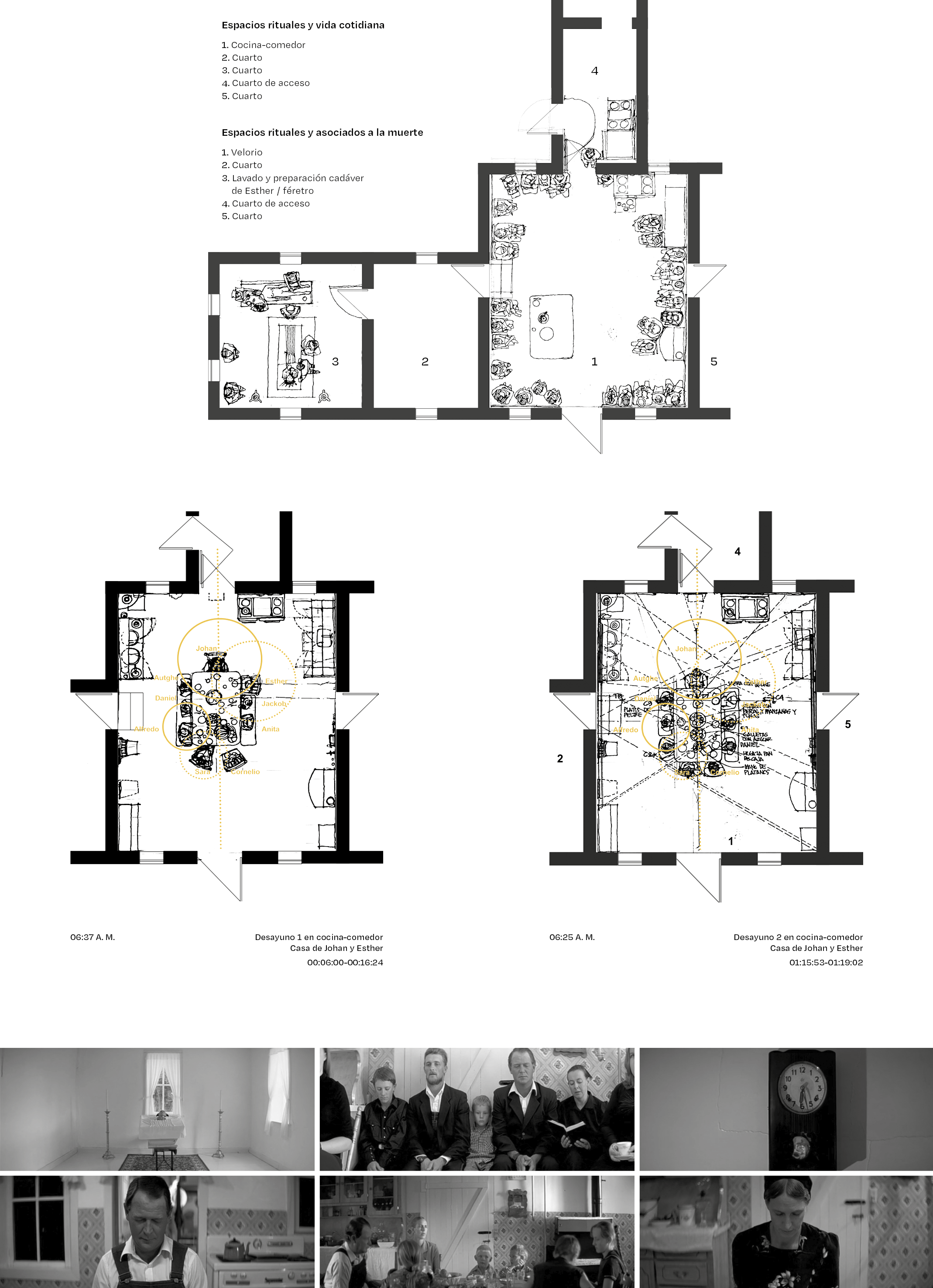

In Luz silenciosa, the following were analyzed: the dawn sequence (mins. 1-5), establishing the film's expanded temporality; the family breakfast (mins. 13-20), showing Mennonite alimentary rituals; the family bath ritual in the jagüey1 (mins. 35-42), evidencing the extension of domestic space; and setting the table (mins. 45-52), revealing inherited choreographies and the temporal transformation of space.

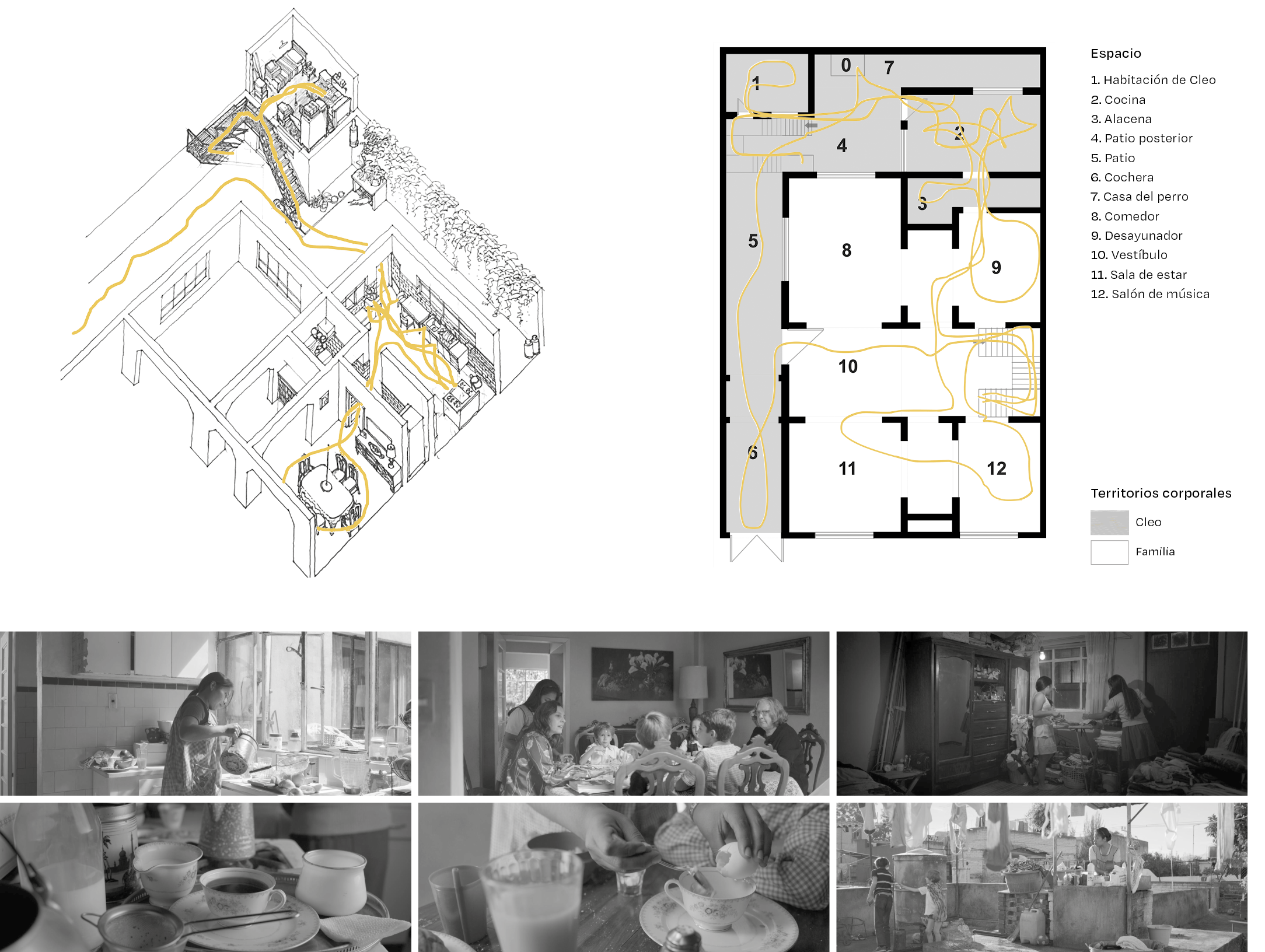

Observed movements were coded according to specific categories: instrumental gestures (domestic tasks), communicative gestures (social interaction), territorial gestures (spatial appropriation), and adaptive gestures (architectural response) (fig. 2).

Figure 2_ Gestural coding system developed for analysis. Key frames from the analyzed sequences are shown with the applied coding, distinguishing between instrumental gestures (domestic tasks), communicative gestures (social interaction), and territorial gestures (spatial appropriation). Specific examples illustrate how different types of gestures reveal socio-spatial dynamics within the domestic space. Source: Prepared by the authors based on frames from the analyzed films.

The developed mapping system meticulously records how bodies occupy and transform domestic space over time, adapting Lynch's (1975) principles of urban analysis to the intimate context of the home.

Spatial reconstruction employed multiple camera angles for photogrammetric analysis. In Roma, this was complemented with additional information from the production designer to document key architectural elements, such as the lateral patio functioning as a spatial organizer, the segregated service staircase, and level differences marking hierarchies. In the case of Luz silenciosa, reconstruction was based on Reygadas's static compositions, identifying the dwelling's linear organization and the direct interior-exterior relationship.

Temporal tracking of movements through specialized software (24 fps) generated precise data on existing patterns of domestic inhabitation:

In the case of Roma, Cleo's displacement speed during domestic tasks averaged 1.2 m/s, compared to 0.8 m/s for the Cuarón family during leisure activities. Cleo's spatial permanence time reached 85% in service spaces, whereas the Cuarón family spent 90% of their time in social spaces. Cleo's spatiotemporal use frequency of the patio reached 12 uses per day, compared to 2 uses per day by the Cuarón family. Interaction patterns between the two were minimal, occurring primarily in moments of care and service.

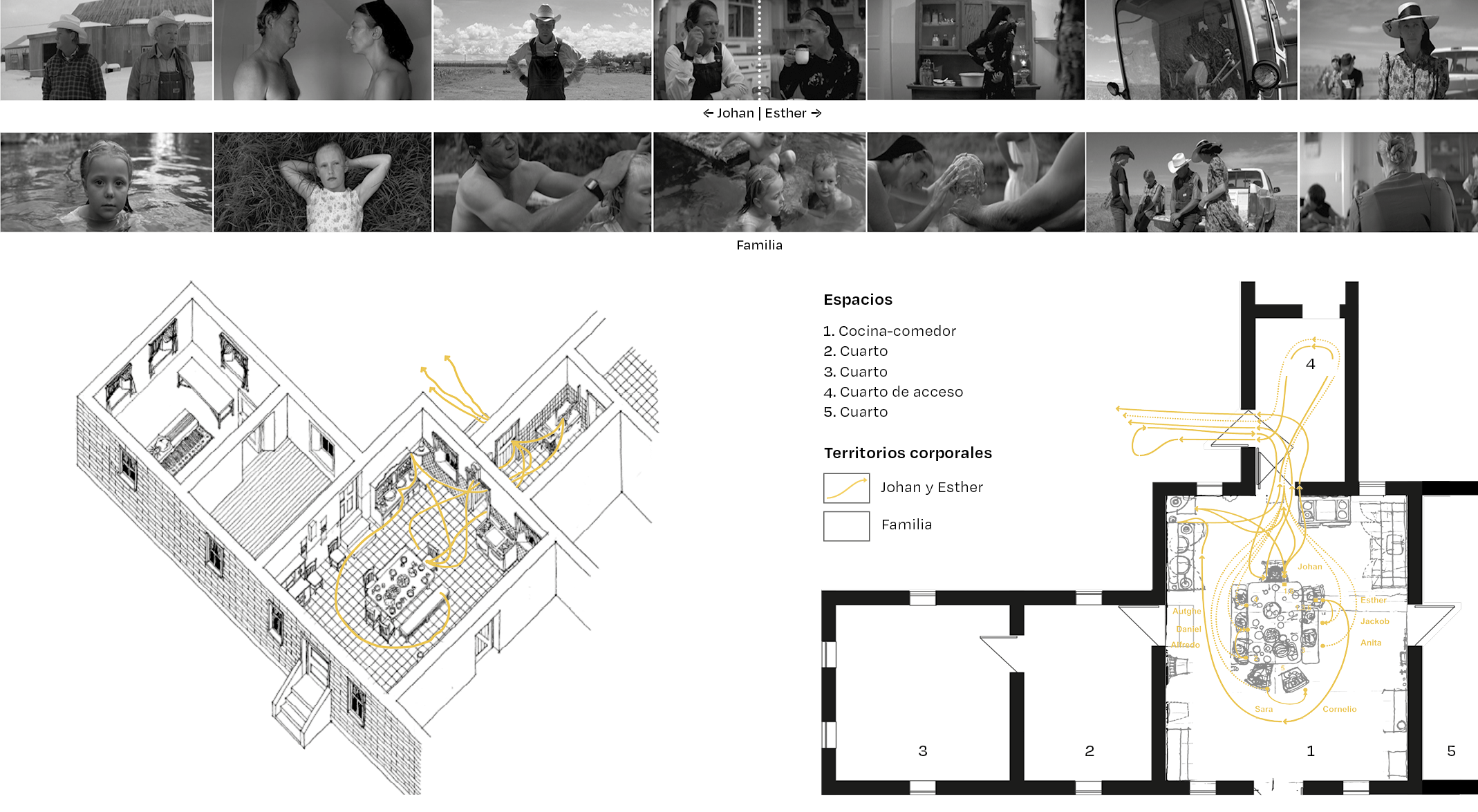

In the case of Luz silenciosa, displacement speed reveals a marked gender division: Johan moves at 3.8 m/s during fieldwork activities, whereas Esther moves at 0.4 m/s in her domestic activities. This difference exposes the gendered spatial structure of Mennonite life, in which the woman is largely restricted to the domestic sphere of the kitchen-dining room. Only a few sequences show Esther outside the house, namely in cultivation spaces and during the family bath in the jagüey, while Johan exhibits broad mobility from home to field, workshop, and hotel, where he meets his lover Marianne. Temporal-spatial distribution further reveals that Esther remains 92% of the time in domestic spaces, compared to 38% for Johan, materializing the patriarchal temporal-spatial division characteristic of the Mennonite household. Spatiotemporal interaction patterns reveal the relational structure of the Mennonite family. Johan and Esther interact spatially during 32% of the film's duration, concentrating their interactions in the kitchen-dining room, immediate exterior spaces, and the car. Johan and Marianne interact spatially during 23% of the film's time, primarily in the field, at Marianne's house, in the truck, and in the hotel where their clandestine intimate encounters take place. Esther and Marianne interact spatially only briefly but with intense dramatic charge in two moments: at Esther's wake and during the resurrection miracle, representing the confrontation between legitimacy of the wife and the transgression embodied by the lover within ritualized domestic space. Finally, the complete family unit—Johan, Esther, and the children—interacts in ritualized spaces during 23% of the film's time, including prayers at two family breakfasts, the ritual family bath in the jagüey, a moment in the truck watching a Jacques Brel video (the only instance of contact with leisure and technology), and Esther's miraculous resurrection.

Integrated visualization transferred data to architectural plans through graphic notation: occupation densities represented through gradations, movement flows through directional vectors, temporal qualities through line systems, and superimpositions showing daily evolution (figs. 3 to 5).

The atmospheric analysis protocol systematically documents how sensory elements contribute to phenomenological experience. Luminic modulation (direction, intensity, chromatic temperature), soundscapes (environmental, domestic, and silence), tactile qualities (textures, temperatures), and visually inferred thermal variations were analyzed (figs. 1 and 2).

The analysis reveals bodily territories as a central phenomenon in the configuration of domestic space. These territories transcend physical delimitation to constitute dynamic fields in which bodily practices, cultural significations, and power relations converge in constant negotiation.

In Roma, territorial configuration evidences an invisible yet effective cartography of social hierarchies. Detailed cartographic analysis reveals systematic patterns: children consistently occupy central areas (60% of the time in main spaces), characterized by freedom of movement and sensory comfort; Cleo mainly uses perimeters and interstices (75% in circulation and service zones), navigating a domestic geography that renders her simultaneously present and absent. Moments of spatial overlap are mediated by specific bodily adjustments, including reduction of bodily volume, acceleration of movements, and avoidance of direct eye contact.

The sequence in which Sofía returns drunk (mins. 62-67) dramatically reveals how emotional states reconfigure spatial perception. Her erratic trajectory through the garage while attempting to park the Ford Galaxie transforms the familiar space into a hostile labyrinth. The children observe from the upper window and Cleo from the service door; even in moments of crisis, each maintains their assigned territory (fig. 3).

Figure 3_ Spatiotemporal cartographies of the house in Roma. The axonometric projection and floor plans reveal the differentiated bodily territories of Cleo, represented by red lines and blue spaces, and of the Cuarón family, represented by white spaces, showing segregated circulation patterns and minimal points of spatial intersection. The diagrams show how the architecture of the side courtyard facilitates a stratified social organization through differentiated flows of movement. Source: the authors.

Luz silenciosa presents bodily territories configured according to ritual principles that establish a more stable yet equally significant organization. Analysis of family disposition during meals reveals a precise bodily geography: the father invariably occupies the head of the table (100% consistency), the mother is positioned strategically for service, and children are arranged according to age and gender, following traditional Mennonite patterns. This ritual territorialization transforms domestic space into a microcosm of the community's social and cosmological order (fig. 4).

Figure 4_ Spatiotemporal cartographies of Mennonite housing in Luz silenciosa. The sequential diagrams document the transformation of domestic space and its rituals throughout the day. Ritual spaces and moments of everyday life are highlighted, showing how religious and cultural practices shape a specific spatial organization based on ceremonial principles. Source: the authors.

Figure 5_ Bodily territories in Mennonite domestic space in Luz silenciosa. The sequential floor plan and axonometric diagrams document the spatiotemporal actions of Johan, Esther, and the family in the kitchen-dining room, from morning prayer and breakfast rituals to the purifying family bath in the jagüey and fieldwork as domestic territories, emphasizing gendered spaces within Mennonite culture. Source: the authors.

The analyzed daily practices reveal domestic choreographies with a performative dimension that continuously constructs spatial meaning, connecting with Butler's (1993, 95) theory of performativity when she establishes that it "is not a singular act, but a repetition and a ritual that achieves its effects through its naturalization."

In Roma (mins. 38-43), the morning family preparation sequence reveals differentiated choreographies that materialize Bourdieu's (1988, 213) economies of time. Detailed analysis shows that the mother takes twelve minutes to prepare herself leisurely; the children use eight to ten minutes, alternating between play and dressing; while Cleo executes fifteen different tasks in barely seven minutes with millimetric efficiency. This temporal-bodily differentiation is not merely practical but profoundly political, reproducing class structures through daily rhythms.

Luz silenciosa presents explicitly ritualized choreographies. The family breakfast (mins. 13-20) follows an absolutely invariable sequence: an initial silent prayer lasting 45 seconds, coffee service by the mother following a strict hierarchical order, a synchronized start to eating, and minimal, measured conversation. This inherited choreography transforms the functional act of eating into a daily sacrament that reaffirms community values.

Atmospheric analysis reveals how sensory elements fundamentally configure the experience of dwelling. In Roma, atmospheric stratification operates systematically: family spaces are characterized by filtered golden natural light (300-500 lx), whereas service spaces rely on cold functional lighting (100-200 lx); soundscapes are differentiated through a fully permeable patio (65-70 dB), filtered main rooms (40-45 dB), and exposed service areas (60-65 dB); and materials establish tactile territories through contrasting qualities (soft/hard, warm/cold).

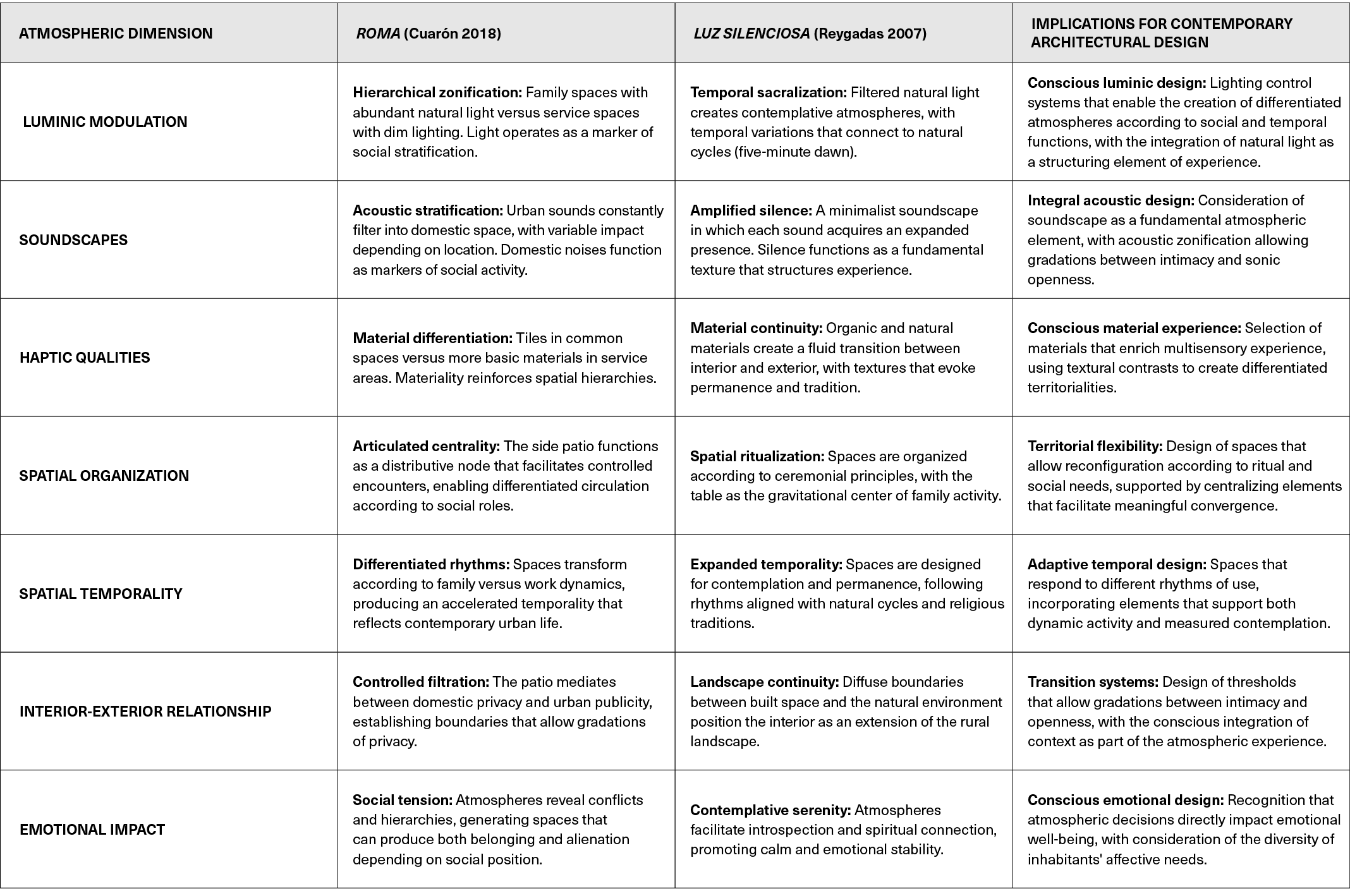

Table 1_ Comparative matrix of atmospheric strategies in Roma and Luz silenciosa. The table summarizes the atmospheric dimensions analyzed in both films and their implications for contemporary architectural design, highlighting how atmospheric decisions can inform design practices that are more sensitive to the multisensory experience of dwelling. Source: the authors.

Luz silenciosa employs atmospheric subtraction to intensify experience. Light functions as a sacred element in transitions between interior and exterior; silence operates as a fundamental texture, amplifying each individual sound; and organic materiality creates sensory continuity, dissolving conventional architectural limits.

The findings establish three fundamental principles that redefine approaches to domestic design from a phenomenological perspective:

1. Adaptive Territories

Design must facilitate continuous territorial negotiation through strategic mobile elements (sliding panels, reconfigurable furniture, flexible partitions), privacy gradients through spatial transitions (changes in height, light, visual permeability, and acoustic quality), and multiple circulation systems (perimetral routes for service and privacy, central routes for interaction, and direct routes for efficiency).

2. Choreographic Facilitation

Space must actively support daily choreographies through spatial sequences that follow activity logic (kitchen-dining-living, bedrooms-bathrooms-dressing rooms), programmed convergence nodes (open kitchens as culinary theaters, wide staircases for conversation, patios as pauses), and incorporated temporality (fast/slow circulations, daily/seasonal transformability).

3. Integral Atmospheric Design

Sensory qualities as primary design objectives require conscious luminic stratification (circadian systems, intense zones and penumbras, individual control), designed acoustic territories (selective absorption, partial barriers, protected silence), and an experiential material palette (warm tactile surfaces, positive aging, explorable textures).

The developed methodology transcends the domestic realm and is applicable to diverse typologies. In educational spaces, analysis of pedagogical choreographies can reveal how spatial configuration facilitates or inhibits learning modalities. In workspaces, mapping real versus idealized flows informs design through the visual recording of movement in space. In healthcare spaces, microgestural analysis can optimize dignity and efficiency, respecting autonomy while facilitating care (table 1).

This research proposes the phenomenology of cinematic dwelling as an innovative analytical framework that integrates cinema's revelatory power with a phenomenological understanding of space to generate knowledge directly applicable to contemporary architectural design. Bodily territories reveal how space is configured through occupation patterns that transcend physical limits, constituting dynamic fields of social and affective negotiation. Domestic choreographies evidence a performative dimension in which daily movements not only reflect but actively construct complex spatial meanings.

Methodologically, the developed protocol integrating microgestural analysis, spatiotemporal cartography, and atmospheric analysis establishes a replicable and transferable framework. Its translation into concrete operative criteria provides tools for architects committed to designing spaces that genuinely respond to the embodied experience of dwelling.

In a historical moment of profound transformations—domestic digitalization, new family configurations, and the climate crisis—the phenomenology of cinematic dwelling emerges as a valuable tool for rethinking architecture from lived experience, offering renewed paths toward a design practice that is more sensitive, inclusive, and profoundly human, and that responds to the complexity of contemporary dwelling.

1 The term jagüey in rural Mexico refers to bodies of water, whether artificial or formed through natural infiltration of the ground.