How to Cite: Quintana-Guerrero, Ingrid and Rafael Méndez Cárdenas. "Inhabiting the Poetic Word: A Conversation with Cazú Zegers". Dearq no. 42 (2025): 21-30. DOI: https://doi.org/10.18389/dearq42.2025.03

How to Cite: Quintana-Guerrero, Ingrid and Rafael Méndez Cárdenas. "Inhabiting the Poetic Word: A Conversation with Cazú Zegers". Dearq no. 42 (2025): 21-30. DOI: https://doi.org/10.18389/dearq42.2025.03

Ingrid Quintana-Guerrero

Universidad de los Andes, Colombia

Rafael Méndez Cárdenas

Universidad de los Andes, Colombia

The interview with Chilean architect Cazú Zegers, conducted by Ingrid Quintana-Guerrero and Rafael Méndez Cárdenas as part of Pabellón 2023, delves into key themes that are essential to understanding her approach to architecture and the practice that underpins it. Central to the discussion were topics such as the connection between poetic language and geography, parametric thinking, the cultural ancestry rooted in the Pacific region, and community-based collaboration.

Keywords: Chilean contemporary architecture, Pacific, parametricism, poetic word, community-based collaboration.

On October 12, 2023, amidst the packed schedule of Pabellón 2023, and following the keynote lecture she delivered at the Mario Laserna Auditorium at Universidad de los Andes, Chilean architect Cazú Zegers graciously offered us a space for an informal conversation. This exchange revolved around lingering questions raised by a review of her work, sparked by her presentation the previous evening.

Ingrid Quintana-Guerrero (IQG): One of the most compelling aspects of your architecture is its connection to the geography of the Pacific. In a video interview for ArqDis1

Cazú Zegers (CZ): Chile has over four thousand kilometers of coastline, offering an incredible diversity of climates and landscapes. This makes the country truly unique: a long, narrow strip that begins in the driest desert in the world, transitions into a vast central valley, and later fragments into the archipelago of Chiloé, where it starts to disintegrate before finally ending in Patagonia. Then, there is Easter Island, located in the middle of the Pacific Ocean, thousands of kilometers away. I like to think of it as our leap to the other side, as it connects us to the opposite shore. I see the Pacific as a mirror reflecting New Zealand, Australia, and Chile. I had the opportunity to give a talk in New Zealand, followed by a couple more in Australia. During these events, I noticed that many of the architects present were from the Pacific region, and I realized we all shared a similar perspective. I asked myself: What binds us together? The answer was clear—the Pacific itself and its countries, which preserve original cultures with indigenous languages and worldviews. I propose that, in the midst of this cultural and planetary paradigm shift we are experiencing, the solutions and answers are emerging from Latin America and the Pacific due to the unique conditions we share.

Rafael Méndez Cárdenas (RMC): Speaking of this Pacific condition, you mentioned earlier that you are going to Popayán. I understand that you have done some work in Cauca, which also has a coastline on the Pacific, though it is a very different Pacific compared to Chile. What are you working on in Cauca? What have you encountered there? What has inspired you?

CZ: I have worked not so much with the Pacific communities but rather with those inland, with a group of indigenous communities called the CRIC (Regional Indigenous Council of Cauca). What I found is that the same thing happens in Chile: they are striving to make a leap toward integrating and generating economies rooted in their territories, languages, and worldviews. It is fascinating, and I think it is something Chile, Colombia, and all the Andean-connected countries share it is essentially one vast Andean territory. I find that profoundly beautiful.

Figure 1_ Wetripantu celebration, Pehuenche people, 2019. Patachoique viewpoint, Andes Mountains, Chile. Workshop Cazú Zegers. Photograph by Lee Busel.

IQG: I would like to discuss another topic that was hinted at in yesterday's talk3: parametricism. Those of us who have followed your work closely know that it has been essential in materializing some of your bold and fantastic architectural designs, such as the Hotel del Viento. At first glance, the use of such tools might seem contradictory to the idea of the vernacular. A moment ago, you mentioned Chiloé, whose architectural production has also been crucial in shaping the ethos of contemporary Chilean architecture. You yourself describe your architecture or project intentions as creating light and precarious works. So, I wonder: how do you achieve a sensitive and haptic dimension despite using BIM and other computational tools? And are there instances where you deliberately choose to forgo these tools in the creation of your work?

Figure 2_ Tierra Patagonia hotel, Torres del Paine National Park, Chile. Project by Cazú Zegers. Photograph by Cristóbal Palma.

CZ: I think we have seen this a lot in the discussions about robotics and the use of artificial intelligence and digital tools (at Pabellón 2023). These are tools—they are not the creation itself! And I believe many students get confused when working directly on the computer, thinking that it is the computer that generates the creative act. For example, I taught a course at Yale, an Advanced Design Studio in the spring of 2019, where my students did everything by hand—they drew by hand—not because I required it, but because it is fundamental. I mentioned this in my talk yesterday: ultimately, my creative process methodology originates from drawing, from sketching. So, I think we need to reconnect with that tool. Or perhaps it is not so much about returning to it as it is about not losing it, because it is a tool that allows you to move into project design without going through pure rationality.

RMC: This discussion about robotics makes me think of a phrase you used a couple of times yesterday: "being faithful to the poetic word." We already understand a lot about the use of words and naming in project management and creation—something that stems from the university and from Godofredo Iommi. But in practical terms, in your methodology, how do you use the poetic word? How does it participate in the process of creating a project? And I am also curious about teaching: how do you guide students through what you call the poetic word?

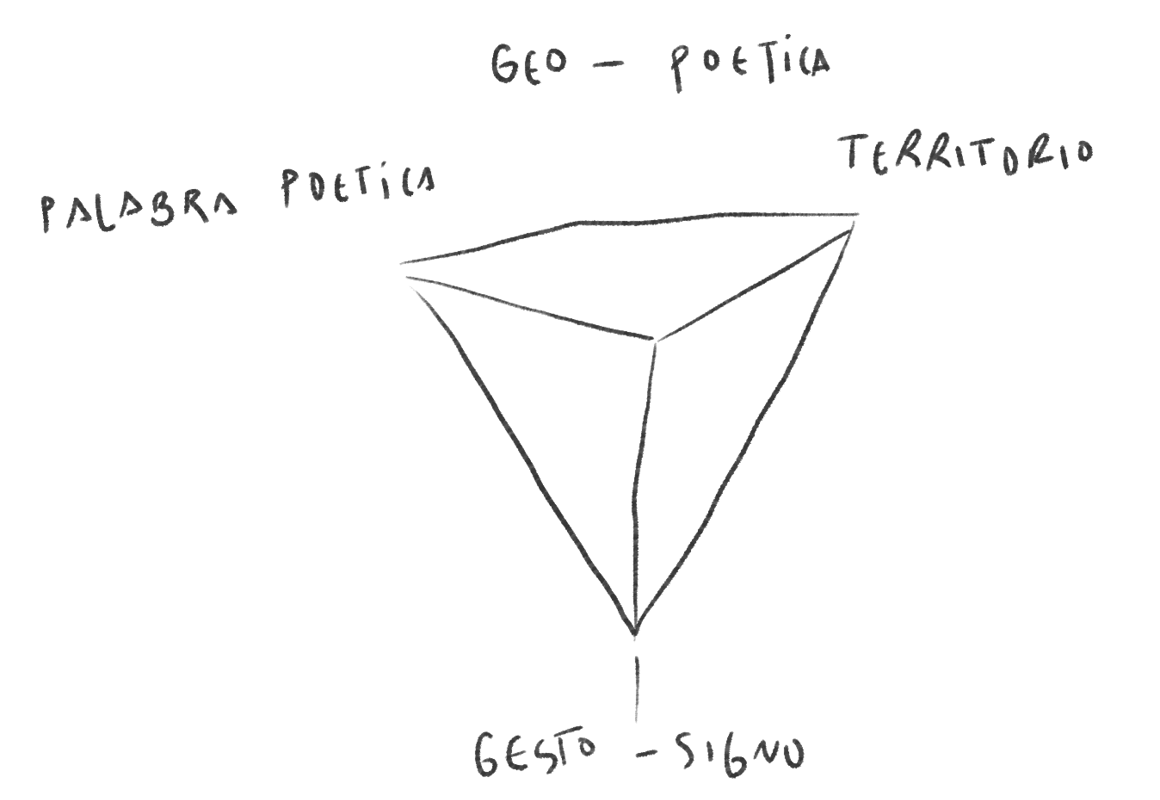

CZ: In my projects, the poetic word is what guides the work; that is why I can remain so faithful to form. I believe this rigor, which is present from beginning to end, is rooted in the poetic word. I may not have explained it the same way yesterday, but it is the same idea as when an ovum meets a sperm and life begins: when the poetic word intersects with the territory, this gesture-sign is born. When named poetically, it carries a sense of truth or a divine breath, so to speak. It can unfold in space and become a constructed form or even a living being.

As Madeline Gannon discussed, robots ultimately become beings—mechanical beings, but beings nonetheless. I have observed something similar with architectural spaces: they, too, become living entities when created in this way.

When I teach, it is the same principle. Teaching is not just about transmitting knowledge through words or what one says; you, as an individual, are a complete instrument of transmission. If you inhabit the poetic word, you can translate it, and each student will discover their own methodology. I believe there is no single artistic methodology; everyone has their own voice. My voice was given to me poetically, so I remain faithful to that word.

Figure 3_ Poetry and territory, Plaza Rombo case. Sketch by Cazú Zegers.

RMC: These elements—the poetic word or gesture, or simply the act of naming, as you mentioned yesterday—are part of the creative process. Architecture cannot avoid being a poetic act. Many architects, especially Latin Americans, have emphasized the power of architecture as a poetic act.

CZ: Of course, I believe that [this power] is Latin American and perhaps specific to the Pacific. This is why I mentioned sensitivity to the territory and the connection to it—because we still have vast stretches of natural beauty and vernacular ways of building. It is all deeply poetic. So, one cannot stray too far from this. If you do, you end up with those buildings of terror that ultimately strip away cultural, personal, and human value. The poet Hölderlin said, "Full of merit, yet poetically, man dwells on this earth." I believe the poetic condition is innate to human beings because it is the essence of creativity. The thing is, confronting creativity is always frightening. You need courage because you are facing a void, an unknown, and being in that space is always uncomfortable. But the longer you can stay in that discomfort, the more original the outcome will be.

You have to trust. I mentioned in an interview a while ago that, in the end, you have to listen to those wild ideas you tend to silence, like my story about Casa del Fuego, where I even started another project just to avoid facing criticism. But those seemingly wild ideas are the truly original ones. You must unleash the wildness within you and not fear it. Do not be afraid to step outside of political correctness or conventional education. We are overeducated; we need to let that wildness emerge. I just thought of something—it may or may not be true: that wildness still exists in our territories. It is embedded within us; we know it. We can be wild.

Figure 4_ Casa del Fuego, Maihue Lake, Chile. Project by Cazú Zegers, 1997. Photograph by Marcos Zegers.

RMC: The miscegenation you spoke of yesterday—we have the privilege of being mestizos without having been separated.

CZ: It is a privilege to be mestizo. I believe it has given us a unique layer, as we essentially have a complete DNA made up of many lineages.

IQG: I want to connect the poetic with the idea of miscegenation: the metaphor you mentioned earlier about fertilization shows how, through language and territory, these biological metaphors consistently appear in your work. We saw this yesterday as well, for example, with the idea of the small fossil in reference to the hotel. I would like to know how this particular interest in science—because your work is poetic but also has a very powerful scientific dimension—developed in your discourse and, consequently, in your practice.

CZ: I would say those interests were always within me. When I was finishing high school and preparing for university, I had no idea what I wanted to study because my interests were incredibly broad—ranging from philosophy to art in all its forms. Astronomy, because of the origins of the universe; biology, because of the origins of humankind; and so on. My mother took me to visit a Chilean artist, Tatiana Álamos, who told me: "If you want to join the elite—in other words, the world of art—then join the best of the elite, which is the School of Architecture at Universidad Católica in Valparaíso."

The truth is, I had no idea what I was getting into—it was the first year of a general program. I thought, "I will study design." Architecture never crossed my mind because I knew many people studying it in Santiago, and it seemed distant from my interests. But two or three months in, while having coffee in the school's kitchen, I met Godofredo Iommi, whom I did not know at the time. He started telling me about Amereida and his thesis that America had not yet embraced its identity as a new continent, emerging instead as a gift or offering; that we needed to found genuinely Latin American cities (as I briefly mentioned yesterday). This narrative, shared over a cheese sandwich, is what made me an architect.

This is where I belong. It is where all my interests converge. Ultimately, I think every field investigates the origins of humanity, the essence of being. That is what unites them for me. I also believe science is entirely creative. It has a methodology rooted in precision and evidence, but the great transformations in science are driven by creativity and creation. When you have an idea—for instance, the concept of the poetic word—it leads to the creation of new technologies that push boundaries and shift perspectives.

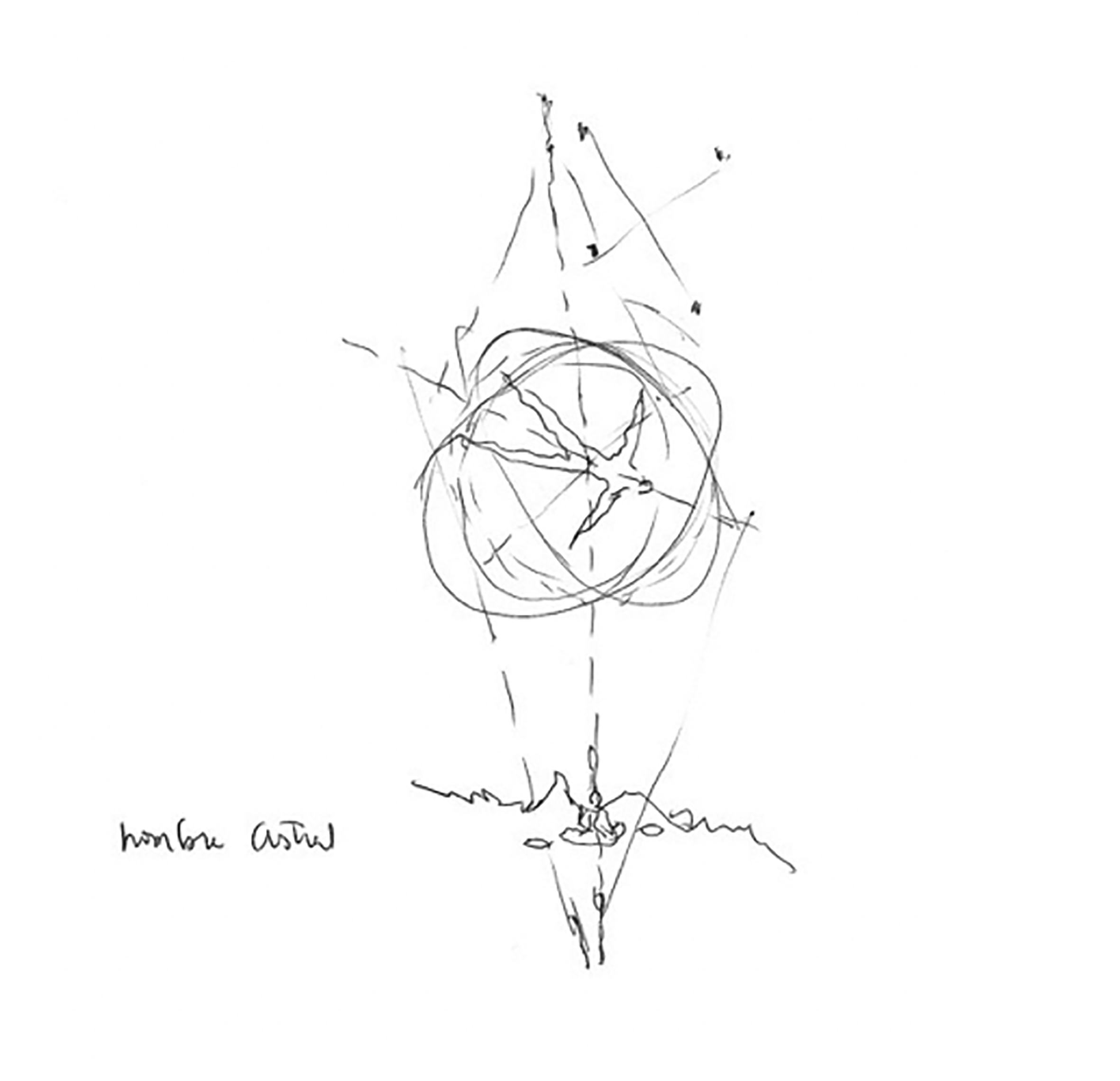

Figure 5_ Astral man. Concept and sketch by Cazú Zegers.

IQG: In addition, the astronomical perspective plays a significant role—it is about origins, from the smallest cell and life within the human body or species to the origins of who we are as entities.

CZ: I find the idea that we are made of stardust and that we are composed of the same matter as the universe and the stars—except for hydrogen—fascinating. We are part of everything, cosmic matter.

RMC: With these ideas in mind, I am curious how you approach the people you work with. When you share your diverse interests, how do you ensure your message resonates? If you bring this narrative to a client, they might think, "What is she talking about? I just want an architect, not someone telling me we are part of the cosmos!" On the other hand, if you discuss cosmogony with an indigenous community, they might connect with you more naturally. Are these dialogues different depending on whether you are speaking to a city client or someone in Chiloé or Patagonia?

CZ: That is a great question! It reminds me of something: I did not know much about Mapuche culture in Chile until much later. When I finally encountered it, I asked myself, "Why does my architecture align so closely with their culture?" I found there was a deep resonance. It is beautiful that you mention this—that an indigenous community would naturally understand these complex ideas. I realized that it must be the territory itself that imprints this understanding of where we come from.

As for how I approach clients, let me share an anecdote: My first house project, Casa Cala, was commissioned by a client because I was a young, recently graduated architect, and it would be inexpensive for him. He came to me with a vernacular-style house that a friend had designed, and I told him, "Look, I do not actually do this kind of architecture—I was honest with him—but I promise you will get everything you want with this house, and more." That is when I started studying the Cala site and its surroundings. For the preliminary design, I did not present him with a floor plan or design; instead, I shared all these ideas. I explained the concepts to him. Meanwhile, the mutual friend who introduced us was saying, "You are crazy." Yet, something I said resonated with the client, and he decided to go for it. He was terrified throughout the process—I could sense his fear. But in the end, when he opened the door to his house, he was truly delighted. "This is my place; this is what I wanted," he told me.

Later, the house won the Gran Premio Latinoamericano (Latin American Grand Prize)4, which was awarded during its first edition. At that time, we Chileans were invited to exhibit, and the jury decided to create this award to recognize the best in Latin American architecture. Winning it as a young architect was incredible for me. It validated my ideas, which were quite unconventional, especially in the context of Chilean architecture at the time. This experience taught me to read the person in front of me and to speak their language. You do not reveal all your secrets to everyone; only to those who understand. And in a lecture, of course, you can share those secrets.

IQG: With these early experiences in private domestic architecture, such as Casa Cala, you illustrate reflections on how the word materializes, becoming body, architecture, and space. But you also mentioned your experiences with the Mapuche people and the hotel. These are examples of public architecture; the hotel is public because it is territorial. In that sense, I would like us to discuss your stance on public work: What attitude should a Chilean architect adopt toward this type of production, given the current sociopolitical context of the country and the renewed recognition of Indigenous peoples in Chile?

CZ: I continue working with Indigenous communities. You learn and understand how to approach things as you go along. For example, the Pehuenche Route is activated through various programs for cultural and sports tourism, and its foundation and entry point is a lodge called Casa Río Experience. Here is another anecdote: at the beginning of this year, a group of young residents came to my studio to tell me they did not want the typical government-subsidized housing—they wanted dignified housing. They had been fighting for this for seven years, had managed to buy a plot of land, and had searched for an architect. They went online, researched, and found me—likely through an interview with the Foundation, where I must have been talking about the territory—and sought me out to design their neighborhood, their dignified housing.

Figure 6_ Experience with Nancy Meliñir and her family. Part of the Pehuenche Route, Arenales sector, designed by Cazú Zegers. Photograph by Benjamín Furo.

The entire public and governmental system for subsidized housing is full of constraints—there is no room to maneuver. These young people had been fighting for seven years, and when someone comes to you with that kind of determination, already carrying the weight of an epic journey without complaints, it is inspiring. Three young people knew the laws inside out, were articulate, and spoke with conviction. Seeing that in residents who are otherwise crushed under the weight of poverty and hopelessness fills you with enthusiasm to act. I am accompanying them now, and we are on that journey together. Projects like these are long-term endeavors. I am also working on a project in Santiago called La Ruta Patrimonial (The Heritage Route), which connects the mountains with the city, as the city currently turns its back on the mountains. Understanding a city not just from its constructed spaces but from its surrounding territory transforms your perspective—it opens up and expands the city. The Heritage Route is part of a larger initiative we call Santiago Capital Outdoor, which explores the city's unique connection to a territory with infinite potential for cultural and sports tourism.

On the other hand, I had a very different experience with a cultural center in a poor community. That project took eight years to complete. When it was finally ready, a new government administration came in and reduced its scale, saying the project was too large. One administration dismantled what the previous one had built, and the whole process became rife with corruption and bad faith. Naively, I believed everyone shared the same spirit of doing good, especially when working in impoverished communities where public and cultural spaces are vital. I ended up partially financing the specialty projects out of my own fees because I thought, "We cannot do this project without proper specialties." It was a huge disappointment—a project that no longer represents me and a missed opportunity. But it taught me invaluable lessons. Now, with this group of residents, my approach is entirely different. One experience leads to another.

I also had the opportunity to design a chapel in Puente Alto, and that was a wonderful experience. It was for a poor community. The priests approached me, wanting to build a better chapel because the one they had was very small. I had no idea how to design a chapel, so I started asking questions: "How large should the doors be? What is the process?" Coincidentally, a theologian came to my office to commission a house and told me, "A chapel reflects the shape of its community, so you must first get to know the community." I organized a group, visited the community, and gathered them in a circle. I said, "I need you to commission your chapel, to dream it, and to tell me what you want." From their input, we created the chapel. The priests wanted to expand their existing chapel, but I thought, "This will be difficult; it is better to start fresh." One of the architects working with me said, "But Cazú, how can we tear this down? The community built it with so much effort. We cannot erase that history." I looked across the street and saw a site that would have been perfect. It turned out to be municipal property, and we secured a benefactor to create an incredible church that revitalized the entire community. Later, I learned from some nuns that young women in the community had asked the priests for permission to study inside the chapel. They said that before the chapel was built, they felt trapped under the weight of poverty: "We came to study, but we had no opportunities." The chapel gave them a space of hope. They even kissed the walls, saying, "This shows us that we do have opportunities." In impoverished areas, public spaces for community gatherings must be of the highest standard. We built this chapel, but the archdiocese refused to recognize it. They told the priests, "Why would you make such an ostentatious chapel in a poor neighborhood? It is common to have modest spaces in these areas."

IQG: What was its approximate budget in dollars??

CZ: I do not remember exactly, but it was not much. The thing is, it is not a chapel; it is a temple. And we said, precisely because it is a poor neighborhood, this must be the best we can deliver. Public architecture, done this way, becomes an act of social transformation. You saw it in Medellín—it is crystal clear.

Figure 7_ Espiritu Santo Chapel, Puente Alto, Santiago, Chile. Project by Cazú Zegers, 2003. Photograph by Cristóbal Palma.

RMC: To wrap up, I have a question about the feminine perspective and the role of women. You mentioned something earlier about your professors' views. It's not that women lack the ability to think abstractly in architecture, but I believe what truly sets you apart is the fact that you approach it without relying on that abstraction.

I also want to tie this to the forms in your architecture and their relationship to the territory. The curved form, as you mentioned yesterday, represents dynamic movement with speed and vitality but also softness and tenderness. This enveloping quality, which could be described as uterine, is present in many of your works—not just in the houses but in many buildings. A space contained within another, like your mother's house with its subtly rotated patio, illustrates this. Would you like to comment on the force of the feminine?

CZ: Yes, I participated in a Mundaneum5 in 2012, held in Mendoza, dedicated exclusively to female artists and architects. There, I realized something significant: amidst a wide variety of approaches and talks—from highly conceptual to those focused on formal practice—I could see the same attributes in all the women present. I believe women are less focused on recognition and more interested in thinking deeply about how to do things and the issues being debated. This care, this sense of nurturing, sensitivity, and respect, is part of the feminine condition. And I am not saying it is exclusive to women—it is a quality of the feminine aspect within all of us. We all have feminine and masculine traits: if I had not embraced my masculine side by riding motorcycles, for example, I would not have had the strength to carry out my practice the way I have. It is about finding balance, a dialogue between the feminine and masculine.

The feminine aspect allows me to work with care and attention. Many people have said that I create curved architecture because I am a woman, but it has more to do with my interests. It is connected to organic forms, scientific principles, and so on. When you think about Einstein's work on light, for example, it revealed that light does not move in straight lines—it curves. In nature, everything is curved. This is the Fibonacci sequence, the law that governs the growth of living things.

I think it is about having the courage to see things from a different perspective. That, I believe, is intrinsic to the feminine. It is what Rimbaud described in his second letter from A Season in Hell.

These poets will exist! When the infinite servitude of women has been broken, when she lives for herself and through herself, when man—until now abominable—has given her back her freedom, she too will be a poet! Woman will find the unknown! Will her worlds of ideas differ from ours? She will discover strange, unfathomable, repugnant, and delicious things; we will take them, we will understand them6.

I think that is the essence of the feminine and what it enables. In a manifesto I wrote, I stated that to save ourselves as a species on this planet, we need to integrate the feminine attributes of being and the perspectives of Indigenous communities into cultural conversations.

We are transitioning from an egocentric system of life to an ecocentric one, where we see ourselves as part of complex systems. I believe women, perhaps because we have historically been marginalized, have developed a greater capacity for resilience and the ability to view things from different angles.

1 Available at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BkIcJYl6-_s (Accessed July 15, 2024).

2 We refer here to the collective poem born from a series of South American journeys undertaken in 1967 by Chilean architect Alberto Cruz Covarrubias (then director of the School of Architecture at the Universidad Católica de Valparaíso) and Argentine poet Godofredo Iommi. This poem subsequently established the conceptual foundations for the creation of the Ciudad Abierta, their campus located in Ritoque on the Chilean Pacific coast.

3 Keynote lecture by Cazú Zegers at Pabellón 2023, October 11, 2023.

4 Refers to the Latin American Grand Prize for Architecture at the Buenos Aires Biennial in 1993.

5 The word originally refers to the Belgian institution created in 1910 under that name, with the aim of safeguarding all human knowledge through a system called the Universal Bibliographic Repertory. Today, it manages exhibition spaces, the archive of its founders, and a website.

6 Arthur Rimbaud, 1986. "Carta del vidente. A Paul Demeny, Charleville, 15 de mayo de 1871". In Una temporada en el infierno, translated by Raúl Gustavo Aguirre. Caracas: Monte Ávila Editores, 1986. The English version here is a free translation by the translator of this interview.