How to Cite: Jaramillo Gamba, Federico. "The Value of Fallible Processes: A Talk with Illustrator Juan Manuel Ramírez". Dearq no. 42 (2025): 13-20. DOI: https://doi.org/10.18389/dearq42.2025.02

How to Cite: Jaramillo Gamba, Federico. "The Value of Fallible Processes: A Talk with Illustrator Juan Manuel Ramírez". Dearq no. 42 (2025): 13-20. DOI: https://doi.org/10.18389/dearq42.2025.02

Federico Jaramillo Gamba

Universidad de los Andes, Colombia

Juan Manuel Ramírez is a Colombian plastic artist based in Bogotá, deeply committed to exploring drawing in all its technical and conceptual forms. This conversation focuses on drawing as a form of study and examines its recognition as a legitimate artwork in its own right. Before we started recording, Juan Manuel kindly showed me around his home and shared the stories behind the drawings on his walls. With enthusiasm and generosity, he described the circumstances surrounding the creation of each piece, along with his techniques, materials, and intentions for the unfinished drawings. However, just as we were about to sit down for the interview, he confessed that he found it challenging to discuss his work, admitting that he sometimes perceived his relationship with drawing as merely a whim.

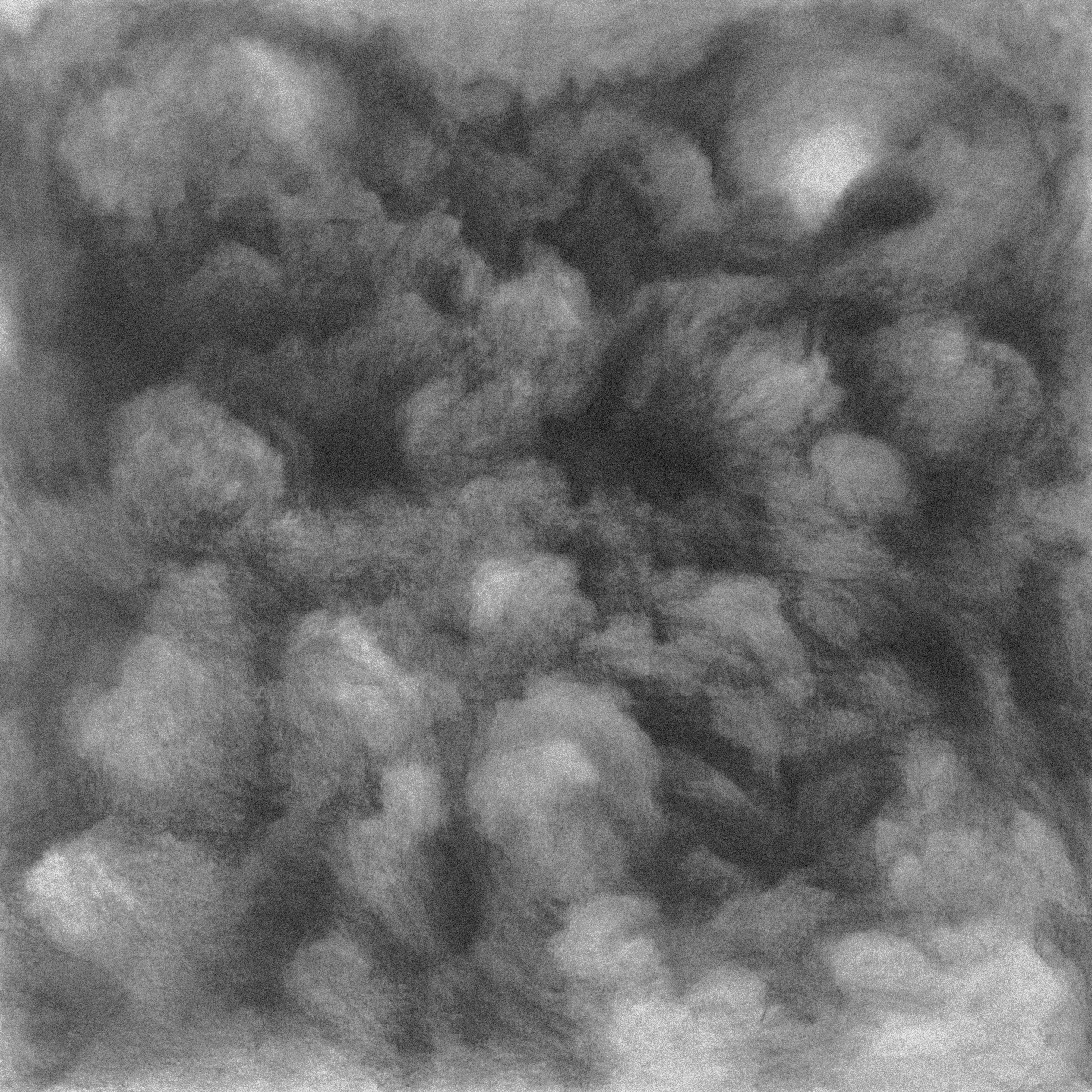

Figure 1_ Smokescreen. Drawing by Juan Manuel Ramírez.

Federico Jaramillo Gamba (FJG): Could you begin by sharing a bit about yourself, your background, and what sparked your fascination with drawing?

Juan Manuel Ramírez (JMR): Well, it began at university, around my fourth and fifth semesters. I was enrolled in a painting class with an excellent teacher named María Morán—an incredible painter—who encouraged us to express our individual interests in painting. She introduced us to various 20th-century artists, one of whom was Egon Schiele. Upon seeing his work, I realized that although he was a painter, he was fundamentally a draughtsman. Over the years, I ultimately came to see him primarily as someone who drew.

At one point, I encountered one of Schiele's paintings depicting an urban landscape—imagine him standing in a building, looking down at the houses, rooftops, and streets below. At that time, I held a somewhat naïve belief that mastering drawing was a prerequisite for painting. Eventually, I realized this was not necessarily true, but back then, I told myself, 'I have to learn to draw.' Egon Schiele's approach to drawing is remarkable. His lines display extraordinary precision, and he maintains a consistent tonal quality throughout each stroke. It is a technical mastery that feels both awe-inspiring and attainable—like listening to a virtuoso musician whose skill is dazzling yet somehow within reach.

It feels like listening to rock music—experiencing Led Zeppelin or Jimi Hendrix play and sensing that you could play like them too. That's how I felt about Schiele. His work inspired me, prompting me to draw more often. I focused on urban views, capturing people and scenes wherever I went. That's when I began carrying half-letter-sized bond paper notebooks and drawing daily. I sketched people on buses, striving to develop precise lines or something close to them.

But then I realized that painting is one thing and drawing is another- not necessarily in that order of learning to draw in order to paint. Painting can also be two-dimensional, but it is not inherently that way. For example, you can see Cézanne's drawings; they are very appealing because you can tell he struggled with drawing. Look at how beautiful this is (shows a drawing by Egon Schiele). It is just a line—no preliminary sketch, no extra marks—yet the tone is consistent, the movement looks perfect, and everything fits together. When you see something like this in person, you see it and say, 'Ah, I could do that.' It seems straightforward; that is what I was discussing before. There is a feeling that it is within reach, but achieving that kind of simplicity is incredibly difficult.

I have come to understand over time and through practice that I always want my work to appear effortless, as if anyone could achieve it. This serves as an invitation for others to try it out. For example, when you listen to The Beatles, their music sounds simple, leading you to think, 'Oh, that's easy; I can play that.' Or consider punk—three chords, three notes—you hear it and think, 'I can write a song like that and sing or shout something over it.' However, when you attempt it, you realize it is something entirely different. My goal is to cultivate that sense of ease.

There is an author named Edward Said, an expert on the Israel-Palestine conflict. He is also a music scholar and has written books on musicology. I find musicology fascinating because I often compare the process of drawing to that of music. At one point, he states that musical composition and interpretation are nearly equally important; sometimes, interpretation can connect you more deeply to a piece than the composition itself. He mentions that a composer—perhaps Debussy—created a piece for students; however, when some performers played it, they executed it with such virtuosity that no student dared to attempt to play it. They believe it is reserved for the gifted, those touched by God. Many painters do something similar—they demonstrate such virtuosity that they create an insurmountable distance between the viewer and the artwork. This elevation of the painter to a divine status leaves the audience feeling incapable of achieving such feats themselves. In contrast, I strongly resonate with artists whose work appears deceptively simple—those who evoke thoughts like, 'Wow, this looks easy'—rather than those who create a sense of distance.

FJG: Unlike other forms of artistic expression, drawing consistently invites curiosity about the process behind it, much like your experience with Egon Schiele. While some drawings evoke a sense of distance due to their technical mastery, similar to the artists you mentioned, a defining characteristic of drawing is that the process remains evident within the work itself.

JMR: What I like most about museums are the drawings by classic artists like Rembrandt and Van Gogh. I once had the opportunity to visit Chicago, where I met the person in charge of drawing and graphic art purchases at the Art Institute of Chicago. He told me, 'You can come here whenever you want. There is a special room for researchers in drawing and graphic art. Just write to us, and you can request to see pieces like a Van Gogh cypress or Cézanne's sketchbook in person.' Unsure about how much to request, I put together a list of about 15 to 20 drawings I wanted to see up close. When I arrived, they told me, 'Mr. Juan Manuel, look, we could not retrieve all fifteen drawings you requested, but we were able to get these seven works for you to study.' The list included an original drawing by Van Gogh, a Rembrandt, a Dürer, a Giacometti, and a piece by David Hockney. You cannot imagine what that felt like. I tried to stay composed, but internally, I could not believe I was sitting in front of an actual Van Gogh. It was a cypress drawn with the bamboo quills he carved himself to make his ink drawings. The quills are usually tiny, so he modified them to have larger ones. The drawing was about A2 in size. What struck me most was that it felt like looking at a child's marks—like seeing someone's handwriting. You could feel the person's presence in every stroke, their imprint, decisions, hesitations, and the moments when their hand wavered.

FJG: Are you implying that drawing is inherently fallible, meaning there is always a possibility of making a mistake?

JMR: I love to see this in painting and strive to showcase it in my drawings—the subtle trembling of the hand. For instance, look at that seascape over there (points to a drawing hanging in his living room). I have created many seas like this one, but with this particular piece, I realize that age is already affecting my pulse. I used a Chinese brush that allows for both fine and thick strokes. It's a play between the two: the thinner strokes create the illusion of distance, resulting in a simple three-dimensional effect. I intended to repeat the lines so they align, carefully placing each brushstroke just below the previous one without touching, like solving a puzzle. At the same time, I gradually increased the thickness of the lines as I moved downward, enhancing that three-dimensional effect. But notice the irregularity; it reveals that my hand is already shaking. While working on this, I acknowledged that age had arrived.

FJG: This indicates that the process and physical gestures are evident. Therefore, drawing requires extensive body training—developing the practice and habit of refining movements so the hand can perform specific actions. What do you think about this physical aspect of drawing in your work?

JMR: I notice that training in my work is becoming increasingly integrated. While physical training exists, so does mental training; the two are inseparable. It's not just about the body or the mind; they merge into a unified process. Continuous drawing allows my hand—indeed, my entire body—to react instinctively to what I have practiced well in my mind. Sometimes, when I teach classes and students say, 'I am going to warm up my hand by drawing repetitive lines,' it strikes me as odd. Why not just dive in? The best training is to observe a face and draw it—that is the practice itself. The body serves as an instrument only when the mind is fully engaged. Sometimes, thinking is just that: nothing more than the act of drawing—thought materializes through the movement of the hand.

FJG: On your page, you mention that since fully committing to drawing, you started to see it as a form of study, presenting this study as a work of art. What do you mean by this?

JMR: What I propose as a work of art isn't something that appears polished or finished; rather, a sketch conveys the feeling that nothing else is needed. My goal is to showcase the process as the artwork itself. In museums, we often encounter unfinished works or sketches by great artists like Rembrandt and Da Vinci, which may seem a bit off-kilter or incomplete. Yet we never think, 'Oh, how strange; it is unfinished.' Instead, we recognize their value just as they are. This idea has lingered in my mind since my thesis work at university: highlighting gestures and the rawness of the creative process. I recall a follower on Facebook once commenting on one of my drawings, saying, 'What a good drawing; it has excellent calligraphy, and the proportions are perfect.' Honestly, such comments make me uncomfortable. They make me wonder—what if my lines weren't so precise? Would that make it a bad drawing? I want to grant myself the freedom to break away from those expectations. Sometimes, when you feel upset, things don't always turn out perfectly. That, too, is part of the process I want to highlight.

FJG: If understanding drawing as a form of study and transforming that study into artwork involves revealing the process, what exactly is being explored within that process? What elements are you examining based on your observations?

JMR: There are many factors; explaining them isn't always easy. Perception itself—observing something and translating it into two dimensions—is challenging to grasp. When I draw a line, I must remain constantly aware of how that stroke relates to the next one. If I sketch your eyelid to a specific size, I must decide how much space to leave before drawing the other eyelid based on what I see. It's about being attentive—not just to the subject in front of me but also to the images and references stored in my mind. Returning to the question, I analyze the intensity of the stroke, the proportion, and even how my drawing might evoke the works of artists like Giacometti or Picasso, among others…

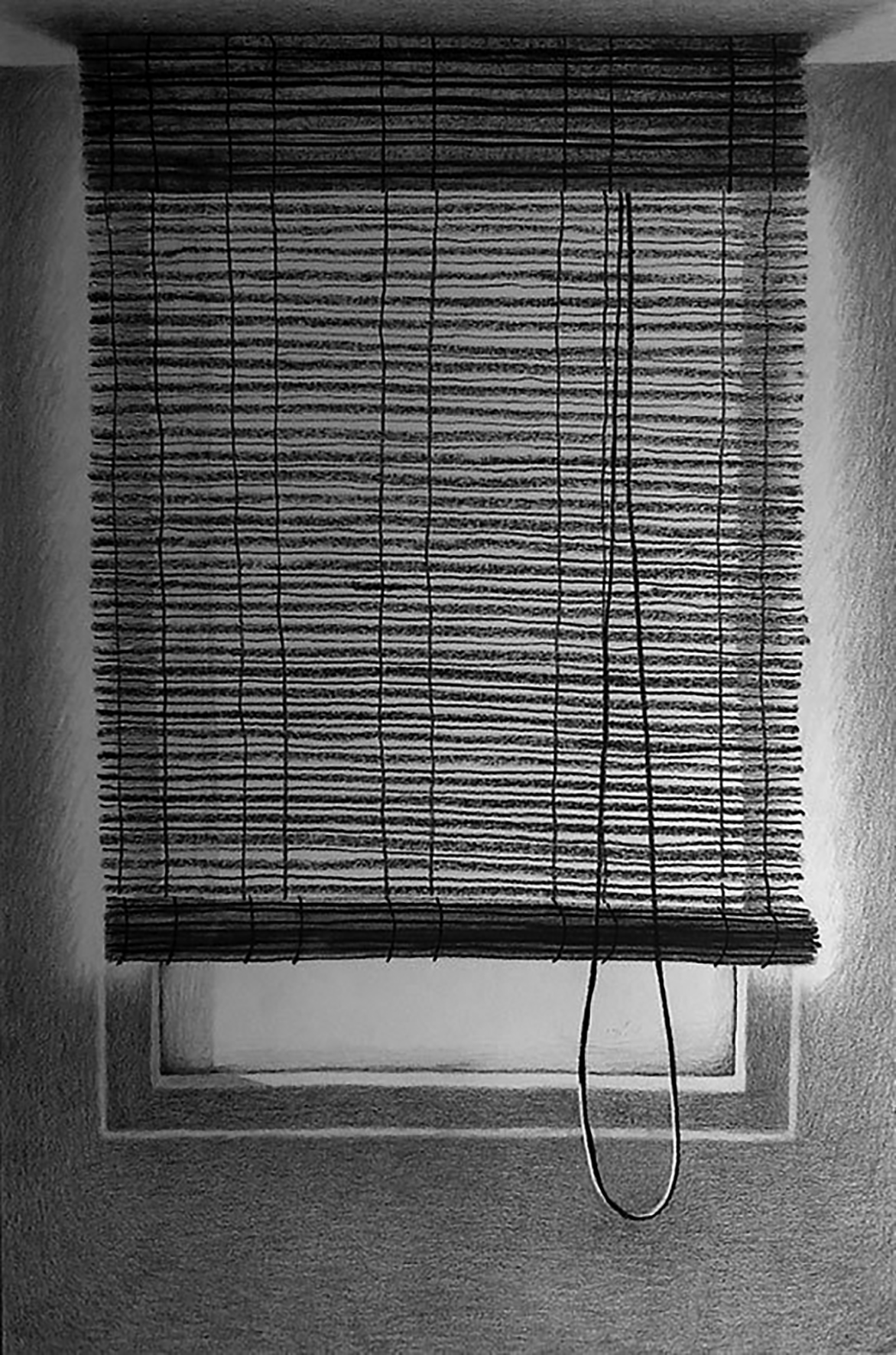

Figure 2_ Window. Drawing by Juan Manuel Ramírez.

FJG: This process includes several interconnected elements, such as your observations, the movement of your hands, the references, and how you visually capture the overall experience.

JMR: Yes, studying is like clearing a path, similar to walking through the jungle and making one's way through the bush. I have written extensively about the process itself, mainly because university students would ask me all sorts of curious questions: 'How do you achieve this?' 'How do you do that?' Thus, I began writing to explain what really happens—because studying is often idealized as if everything falls into place by magic. In reality, countless factors come into play. Even something as simple as drinking a strong black coffee can influence your perception, pulse, and concentration. Ideally, one could isolate the act of drawing from everything else—digestion, exhaustion, lack of sleep, and even the emotional swings of falling in or out of love.

For me, studying involves constant practice. I must keep creating; otherwise, I become rusty. Take those nude figure drawings in the room—you can see the fluidity and the precise representation of the reclining woman with the light; everything fits perfectly. However, I spent five years without drawing a human figure. I hired a model, and when I started drawing again, it felt like, 'Oh! How do I do this? Where do I place the line?' It was like starting from scratch; you can see in the drawings that something doesn't quite fit. The proportions may be correct since I have been drawing for so long, but the freshness and fluidity are lacking. The stiffness is apparent, and it's not just a rigidity in the strokes but also the concept. How is the model positioned? How do I frame the composition so that it looks appealing on paper?

FJG: Your work showcases a diverse range of subjects, settings, and techniques. Is there a connection among these elements? Does your choice of specific techniques or materials influence your approach to different subjects or settings?

JMR: I love classical art, still lifes, portraits, and landscapes. These themes are timeless, and I strive to create variations of them. Take still life, for instance; I focus on the small details and tiny objects. My choice of subjects can sometimes be entirely spontaneous. For example, I might be working on a sky, notice a nearby notebook, walk into a room, see a saltshaker, and think, 'I am going to draw that.' Suddenly, my focus shifts. A comment from my university friend, Juan David Castaño, has always resonated with me. He once pointed out that Picasso could create something in his recognizable, fragmented style in the morning and then draw something entirely different by the afternoon. He didn't try to maintain a rigid and consistent style like Botero. Botero does this deliberately, upholding a style that, to me, has commercial validity—it makes his work instantly identifiable. However, when I studied Picasso, I realized that his way of thinking remained consistent throughout his work despite his use of vastly different styles. Even if the approach changes, you can always recognize it as his. This is something I aspire to—a kind of versatility that allows me to transition fluidly between various styles, techniques, and themes while still maintaining the essence of my process.

FJG: As a drawing teacher, what pedagogical value or role do you believe drawing provides to students entering the creative field? This is especially significant considering that today's architecture, design, and art students have digital tools that relieve their hands of certain responsibilities.

JMR: Allowing oneself to make mistakes, to have a shaky hand, and to mess up proportions. At 50 years old, I still struggle with this sometimes. I follow artists who work with tablets, artificial intelligence, or illustration programs, and their creations are impressive. However, a question arises: how would they fare when drawing with a pencil? One of the biggest challenges in traditional drawing is the absence of a Ctrl Z. I recognize this isn't easy, but that is the beauty of showcasing hand-drawn work. What interests me most is teaching how to navigate mistakes rather than avoid them. It's akin to speaking and stumbling or stuttering. For some reason, people do not grant themselves the same freedom when drawing, which has always amazed me. You can dance and sing in public, but sharing a hand-made drawing? I have had students who refuse to show their work and become frustrated when I ask them to present an exercise. They feel as though they are exposing a part of themselves. When you ask someone about their drawing skills, they almost always respond, 'I draw terribly' or 'I draw like a child.' Sometimes, I ask myself why I should think about this pedagogical intention, but I also draw with a pedagogical intention. I draw to make people crave it. That's what moves me when drawing—to express and share my artistic taste through drawing.

FJG: You have taught in both academic and university settings, and today, the idea that research can be conducted through creative practice—studying through creative processes—is gaining recognition. Have you encountered any challenges in validating this concept? What potential do you see in creating as a form of research?

JMR: First, I find it strange that a strong preconception persists in academic settings—that one must learn academic drawing before pursuing other forms of expression. This notion is treated as a rule, implying that we all must undergo rigorous 19th-century training before we can deconstruct it and draw like Picasso. This mindset prevails in most academic institutions, yet it exemplifies an arbitrary order that does not hold up. It mirrors my naïve early belief that I needed to learn to draw in order to paint. Over time, I realized that's not how it works. Drawing is drawing; I do not draw merely to fill in with color later. If someone chooses to do that deliberately, that's one thing, but the belief in a necessary sequence to learning—first mastering realistic academic drawing before moving on to anything else—remains a challenge in educational environments. It's bizarre because, for over a century, we have observed Picasso and contemporary artists creating drawings entirely unrelated to the 18th or 19th centuries. Yet this belief persists, almost ingrained in our DNA: if you do not draw academically or realistically, you are not a good artist. This perspective contributes to why people find drawing so intimidating; it carries a weight of expectation. Even the notion of perfection in drawing stems from a Renaissance mindset. When we hear the word 'perfect,' we often think of Da Vinci drawing at 60, after a lifetime of study and refinement. But for me, drawing is about rethinking this every day because I, too, still carry that ingrained pursuit of perfection instilled in me.

FJG: Regarding perspective and the geometric concept of drawing...

JMR: If you don't construct perspective as you perceive it or as it appears in a Renaissance painting, then you aren't a good artist. It's incredible how profoundly the Renaissance has shaped our thinking, almost as if it has rewired our brains. I recall a text by Gombrich about Picasso that discusses how he embodies a reimagined form of Platonism; it feels like a return to the same concept. I mean, Picasso as revolutionary as he may seem, represents once again an ideal of perfection, an idea of proportion. Presenting this in an academic setting is challenging. That's why I began writing a blog as if I'm secretly telling the boys and girls, 'Hey, it's not so complicated.' And yes, the little things affect the process—drinking coffee, eating bandeja paisa before drawing—it all matters. This is not a negative aspect but part of the process. There's this ideal of doing everything in order, from top to bottom. But that doesn't happen; everyone is different, and every mind is unique. When you factor in the ideas and biases you carry from references like Da Vinci, your emotions significantly influence your drawing. Sometimes, I find myself mentally debating with artists who are no longer alive—like Giacometti—imagining him standing behind me, observing my work, and asking, 'What are you doing?'

FJG: Finally, Juan Manuel, I'd like to understand your approach to landscapes in your drawings. What do you perceive, and how do you connect with each landscape?

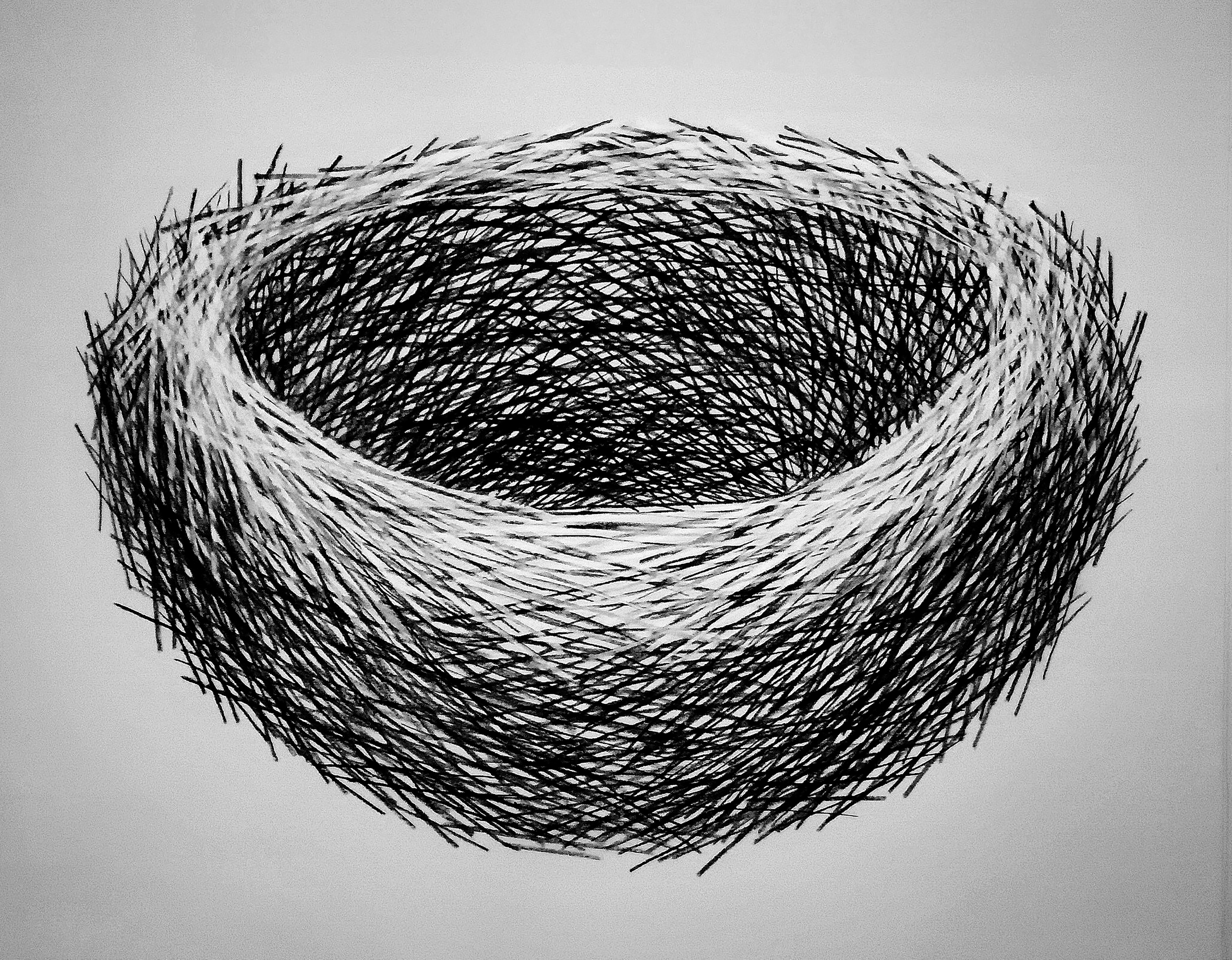

Figure 3_ Nest. Drawing by Juan Manuel Ramírez.

JMR: To me, the fundamentals of drawing consist of dots and lines. In 2007, I experienced a vision or epiphany that inspired me to create drawings solely with dots and lines, leading me to explore nests. Numerous thoughts emerged at once. Birds construct nests—structures made entirely of small sticks—without tying, gluing, or nailing. I contemplated translating that physical sensation into drawing, using only interwoven lines and avoiding shadows, essentially replicating the nest's structure. From there, I began creating drawings of grasslands, starting with tiny dots on the horizon and then expanding the lines.

One aspect I genuinely appreciate about Asian art—rooted in my passion for kung fu—is its concept of repetition. I created an entire series featuring grasslands and seas by simply repeating a line, varying its size, and watching the landscape take shape. Clouds followed this same principle. At one point, I was smudging charcoal on paper to create clouds, but it didn't feel quite right—it lacked that repetitive motion. Then I realized clouds consist of tiny water particles, so I drew them with dots instead. For the starry skies, I covered the entire surface with repeating lines until only small white gaps remained between them. These gaps transformed into dots, and the fascinating aspect of this is that it appears more realistic than if I had painted everything black and then added the white dots. The uneven spacing lends a natural depth; it feels like one star is farther away than another. These landscape drawings do not come from memory; they emerge technically, appearing by themselves at the moment. The waves in my sea drawings manifest on their own.

The landscapes emerge as a blend. They are no longer just clouds; they are clouds alongside grasslands and open spaces. This process involves creating landscapes and natural phenomena through repetitive gestures—in other words, breaking down the landscape to uncover which gesture, line, or point resonates the most. For instance, I have a concept that I still do not know how to resolve: how to represent lightning when it strikes. How do I depict that on paper so you can perceive the flash at night? I requested a Rembrandt engraving titled The Three Trees from the Art Institute of Chicago. When I viewed it up close, I felt it contained a true essence of light. It's similar to when you see a comic; yes, you know it's a drawing, but at the same time, you are entirely immersed in the story.

Figure 4_ Grassland landscape with clouds. Drawing by Juan Manuel Ramírez.

Figure 5_ Nocturnal landscape. Drawing by Juan Manuel Ramírez.