Somatic Embodiment in Architectural Education and Practice: Workshop Curriculum, Report, and Learner Responses

Galen Cranz

galen@berkeley.edu

University of California, Berkeley, USA

Veronika Mayerboeck

info@allesoderlicht.com

ALLES oder Licht: Design.Education.Research, Austria

Carina Rose

carinarosedesign@gmail.com

Independent Researcher

Sarah Robinson

sarah@srarchitect.com

Università Iuav di Venezia, Italy

Received: December 2, 2024 | Accepted: July 21, 2025

This paper argues for the importance of somatic embodiment in architecture and presents a workshop protocol employed at the 2024 summer school Moving Boundaries: Architecture and the Human Sciences in Stockholm. The workshop introduced somatic practices for architects and designers, and we share the protocol as a resource for educators and practitioners. Positive participant feedback highlights the value of teaching somatic methods in design, supporting the need for further research on integrating body awareness, movement, and well-being into architectural pedagogy and practices.

Keywords: Somatic practices, embodied design, architectural pedagogy, movement and space, experiential learning, workshop protocol, kinesthetic engagement.

theory of somatic embodiment in architecture

Architecture houses the body and structures the patterns of our daily lives. This may seem obvious—were it not for the fact that only recently has the discipline turned its attention to such seemingly mundane matters. Fueled by research across sciences and humanities—after centuries of neglect—a renewed concern for the body and celebration of bodily experience is now underway. A wide range of findings converge on the situated, embodied, interdependent, and material nature of all biological, cognitive, and emotional processes. We can no longer separate mind from body, or bodies from their surrounding worlds. The multiple crises we face today—climatic, ecological, social, and individual—can all be traced to divisions long assumed absolute. For architecture to turn its attention to designing for the body is, arguably, one of its loftiest aims.

Re-orienting architecture to value the body and bodily experience is more complex than it seems. Architectural history reveals a conflicted relationship with the human body (Robinson 2020; 2021a, 2021b). In the Greek tradition, the body was revered as an ideal form, seeding the Vitruvian canon, where parts of the body—finger, palm, foot, cubit—defined architectural proportions. This Ptolemaic microcosm-macrocosm worldview resurfaced in the Renaissance with Da Vinci's homo quadratus. But this holistic vision unraveled with the Cartesian physics of the Enlightenment. Charles Perrault, a key advocate, famously claimed that "the body never supplied architecture with any of its ideas" (as cited in Mallgrave 2010, 43). The earlier cosmic body gave way to one reduced to external measurements—a fragmented, impoverished view that still shapes architecture today.

Architectural education remains firmly ensconced in this Cartesian tradition. Architects are taught physics and mathematics, but rarely ecology, behavioral science or sociology, and anthropology. As a result, the human being for whom we design is understood primarily in physical terms. The body is still conceived exclusively through external dimensions to size doors, stairs, and sidewalks, or through thermal comfort, reduced to a narrow bandwidth of a few degrees.

Yet we now know that the body is the foundation of all experience, the dynamic material basis of our being in the world. Our cognitive capacities—imagination, memory, learning, creativity—are all thoroughly embodied. Still, architectural design tends to undervalue this basic corporeal fact. This is compounded by the growing use of computerized design tools that further distance us from rich reservoirs of bodily knowledge. We therefore advocate to integrate somatic practices into architectural design education. These practices engage the whole person, following Hanna's definition of soma as the body experienced from within (Hanna 1995), a concept rooted in the phenomenology of an embodied, enacted, situated, and affective mind (Varela, Thompson, and Rosch 1993).

In design and architecture, somatic approaches prioritize sensory experience, movement, and embodied perception throughout the creative process. Drawing from disciplines such as the Feldenkrais Method, the Alexander technique, and Body-Mind Centering®, they provide tools for deeper engagement with space, materiality, and human experience (Spatz 2015; Hanna 1970). Somatics in architecture informs spatial awareness, scale, and user interaction, encouraging a shift from purely visual or formal concerns toward lived, kinesthetic experience (Böhme 2017; Leatherbarrow and Mostafavi 2002). Given the diversity of somatic methods, however, precise, context-specific definitions are essential to avoid reducing them to vague "body awareness" and to clarify their role within design discourse.

Precedents to such an embodied approach to teaching architects begin with the sensory training developed in the foundational course of the Bauhaus in the 1920s. Pioneered by Johannes Itten and László Moholy-Nagy, this training systematically engaged the tactile and kinesthetic senses. It was later expanded by Oskar Schlemmer to include movement and dance, by Josef Albers to address color perception and visual contrast, and by Otti Berger to explore textile textures and material sensibilities. A further example is the so-called anti-school of architecture Global Tools (Bruyère, Geel and Petit 2022), an experimental pedagogical network founded by a group of radical Italian architects and designers. Global Tools aimed to reimagine architectural education through direct bodily experience, craft, and alternative media. The initiative also involved a broader international network of collaborators, including influential figures such as Richard Buckminster Fuller.

Another example is the environmental awareness workshops pioneered by the landscape architect Lawrence Halprin and avant-garde dancer Anna Halprin. In the mid 1960s, they organized a series of experimental, cross-disciplinary encounters in San Francisco and along the northern California coast that engaged dancers, architects, landscape architects, artists, and others in a process designed to facilitate collaboration and group creativity. Similar embodied approaches emerged in the work of Merce Cunningham, who treated space as choreographic material, and Trisha Brown, whose site-specific performances like Roof Piece activated architectural surfaces.

The integration of somatic practices into architecture should not be dismissed as informal extracurricular activities—like stretching during coffee breaks—as such comparisons obscure the depth and rigor of existing research. Scholars and practitioners have demonstrated that somatics can serve as a serious methodological and epistemological tool in architectural practice. For example, from 1989 to 2018, Galen Cranz, influenced by both sociology and the Alexander technique, taught a course called Designing for the Near-Environment—later renamed Body Conscious Design—at the University of California, Berkeley's Department of Architecture (see Cranz and Rushton 2024). This remains the longest running course on somatics in architecture worldwide.

Recent initiatives include Ferreira's Corporeal Architecture course at the University of Stuttgart, which integrates performance art and design to explore embodied spatial experience (cf. Ferreira 2021). Gálvez Pérez (2019) investigates embodied spatial perception through somatic and performative methodologies, particularly in her concept of the somatic gaze. Skrzypczak (2021) develops somatic movement principles tailored to architectural design, emphasizing the operationalization of felt space. Spatz (2015), though not an architect, provides a transferable framework for somatics as a research method across disciplines. Dupuis's (2024) doctoral work at the École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne (EPFL) explores choreopolitical and embodied approaches to architecture, demonstrating how bodily awareness can reshape spatial thinking. Çelik Alexander (2017) further examines the role of kinesthetic knowledge in modern design, linking aesthetics and epistemology through bodily experience. Several design theorists also call for somatics in design education (Sfligiotti 2021; Höök et al. 2019; Martin, Filk and Schulze Heuling 2021).

Collectively, these contributions establish somatics as a rigorous, practice-based research method within architecture, far from a peripheral or supplementary concern. They demonstrate that somatic methods offer students new ways of perceiving, designing, and inhabiting space, fostering deeper awareness of the body's role in spatial experience and creation.

introducing moving boundaries

Moving Boundaries is a two-week, extra-curricular architectural course held in various global locations.1 It combines site visits to significant architectural works with field trips to explore architecture in diverse cultural contexts, alongside lectures from leading scholars and scientists, as well as multi-day practical workshops. The inaugural course, held in 2022 in Santiago de Compostela, Spain and Porto, Portugal, focused on neuroscience but soon expanded to encompass the broader human sciences. As these disciplines are inherently embodied, the body has emerged as a central theme of the program, with bodily health becoming a core objective. The Moving Boundaries course pedagogy has since moved from a lecture to a design studio format, however, finding ways to integrate the embodied mind into design courses has been a gradual process. This paper reports on the first full-fledged workshop at Moving Boundaries in 2024, which we share with architects and educators as a model for incorporating somatic practices into education, design, and architectural office practices.

report on the implementation of the embodied design workshop

Structure and Content of the Embodied Design Workshop

The workshop has a four-day structure, with a specific focus for each day:

Day 1. Interoceptive Awareness: The Intimate Inner Body Landscape

Day 2. Proprioceptive Awareness and Interaction: The Personal Outer Body Field

Day 3. Co-Creational Action: The Body in Interaction with Others and the Environment

Day 4. Reflection and Sharing

The workshop guided participants through a somatic journey across nested layers of bodily experience: from the intimate inner body, to personal and social interaction, to co-creation within spatial environments. Visualization supported the integration of each layer. Participants engaged with the body as a complex, living system—attuned to inner and outer nuances, and capable of discerning and expressing from a deeply situated place. Moving from cellular to biospheric, personal to collective, the prompts expanded relational awareness. This fluid navigation of somatic layers cultivates the body's intelligence as a responsive, empathetic design tool.

The experiential exercises in the workshop derive from yoga, the Alexander technique, body conscious design, and Body-Mind Centering®, while the movement modalities derive from Body-Mind Centering®, developmental movement, six viewpoints, authentic movement, ecosomatics, contemplative dance, contact improvisation, real time composition, and contemporary performance (Wait 2023). Practices leading to co-creation derive from the sensing space methodology (Mayerboeck 2024; Mayerboeck, Höök and Duarte, in preparation).

The interdisciplinary backgrounds of the four workshop leaders

All four workshop leaders share professional ties to architecture, both as practicing architects and as educators within the field. Beyond their architectural expertise, they bring diverse embodied practices and somatic disciplines that enrich the learning experience for workshop participants. Two of the leaders are experienced dancers, integrating a deep kinesthetic awareness and movement vocabulary into the architectural context. Another leader is a certified teacher of the Alexander technique, contributing specialized knowledge in posture, movement efficiency, and somatic re-education.

The leaders' diverse and unique backgrounds facilitate a richer, more layered learning environment, where participants are exposed to varied perspectives on how the body can engage with space, design processes, and collaborative creativity.

Participants

Twenty participants from Europe, North and South America—primarily architects, architectural students, or designers—took part in the workshop. In general, no prior movement training was required, and all mobility levels were welcome. The four workshop leaders and a videographer all took part in the exercises, creating a stronger bond and sense of community between participants and leaders.

Workshop implementation

Introductory session

We began by sitting in a circle—but subverted the usual use of chairs (Cranz 2000, 2017). Instead of sitting, participants lay on the floor with their lower legs supported by chair seats at a right angle to their thighs and torsos, similar to restorative yoga. This positioned their heads in the circle's center but prevented face-to-face contact, so introductions were made by voice alone (fig. 1). To encourage speaking when moved to speak, we used an empathic listening practice (Vopel 1994) where participants numbered themselves without a set order. Without seeing each other, they relied on voice tone and intuition to decide when to say the next number. We repeated this with participants speaking their names, then sharing their interests in the workshop—always without face-to-face contact.

Figure 1_ Workshop participants using chairs as leg rests: the best use of a chair. Source: Photo by Cranz.

One participant reported, "From the very first minute we got this encouragement to lay down on the floor, just look at the ceiling or close our eyes. And it gave us so much freedom, like this permission to move or dance. This kind of experiment […] also gave us […] intellectual freedom, I would say, to create, actually […] It was surprising that we need this permission, you know?"2

Another participant was surprised by the power of listening to voices first: "Before studying the faces of one another, voices felt as if bells were ringing, bringing variation in timbre and tone to the event."

Day 1. Interoceptive Awareness: The Intimate Inner Body Landscape

This day aimed to activate our inner body landscape. We opened with a sensory awareness exercise to help participants explore how their feet relate to overall body alignment. Standing in a circle, each person identified where weight was most and least concentrated across four-foot quadrants. A show of hands revealed wide variation among bodies. We then asked what shifts—often in the hips or spine—might allow for more even distribution. To delve even deeper into the experience, participants threaded their fingers between the toes of one foot and compared it to the other. The touched and slightly expanded foot was usually described as warmer, softer, and more grounded. This simple intervention illustrated how design affects bodily health—particularly the impact of shoes—and we suggested a challenging follow-up assignment: to design shoes that are both anatomically sound and aesthetically fashionable.

We moved on to replicate a study exploring how cortical (logical thought) and subcortical (involuntary processes, emotions, dreams) states of consciousness affect the quality of drawings—an essential starting point in architectural design (Cranz & Chiesi 2014). Students first activated their cortical brain by solving arithmetic problems (addition, subtraction, division, multiplication), then made two drawings—one of a handle and the other of a lamp. Next, in pairs, participants were guided to access subcortical awareness by focusing on their internal organs, specifically the kidneys. One partner placed a hand on the other's lower back while both were guided—by someone in a subcortical state—to sense the blood flow into and out of the kidneys. To illustrate the body's involuntary responses, a loud noise (a dropped stack of books) startled participants despite prior warning—demonstrating the kidneys' reactivity independent of conscious thought. After switching roles, participants repeated the drawing exercise.

We then compared both sets of drawings. Cortical versions were typically small, angular, and flat; subcortical ones were larger, curvier, and more three-dimensional. One participant later recalled, "The subcortical drawings were alive, the cortical ones static". This led to a discussion about which states support different design tasks. While the cortical state seemed efficient, many found the subcortical state more generative and creatively rich. In the words of one participant:

what I really enjoyed was that we also talk or hear a lot at work about productivity. Productivity, that's why we're so task oriented. You might think that the subcortical exercise would take longer […] that it's less worth [while] because you're not as productive. And yet it felt like for most of us, the output was so much richer, if anything you could say that [it] was more productive and more effective, while also being more enjoyable. And that was very eye-opening for me.

At the end of this day, another participant reflected: "We did not need to speak to each other [in order] to feel connected […] [but] after the first day of our workshop […] we [naturally] became very connected to each other." Trust of one another and connectedness were recurrent comments.

Day 2. Proprioceptive Awareness and Interaction: The Personal Outer Body Field and Relation to Others

Day 2 covered activities from movement exercises to choreographic improvisations, and ended with a short co-design exercise. We began in a circle acknowledging presence and breath as ways to settle our nervous systems. Participants rested on the floor with closed eyes for an internal somatic exploration. Starting with awareness of cellular breathing as an invisible yet primary movement, we introduced the skin as the home, a permeable envelope, and a boundary of self. Scans of bodily systems (fluids, organs, muscles, skeleton) were paired with attention to senses, thoughts, imagery, and emotions. By visualizing and moving the body's six limbs (arms, legs, head, and tail) and navel radiation, we touched upon developmental patterns, establishing the deep inner body as a source of creative agency.

Participants gradually stood and opened their eyes, continuing to sense their internal landscape as it shifted into vertical alignment. They walked and paused in their natural rhythm, observing spatial distances between themselves, others, and the environment. Moving first along grids, then curves, they activated proprioception and resonance, guided by variations in gaze (direct, peripheral, between) to explore spatial awareness and navigation while maintaining internal rhythm. In moments of stillness, we invited them to visualize nested spatial layers—from inner body and skin, to peripersonal space, building, city, and biosphere—evoking a somatic and collaborative continuum (Rose 2025a, 2025b) of situatedness and belonging. Sound bowls supported this attunement, encouraging vocal expression and deepened connection to self and space.

While participants moved through the space, they allowed for rhythm, speed changes, and influence from others to expand their awareness of relational dynamics. This amplified conscious co-creation, and organic gatherings emerged, which we directed into groups of five or six. Groups improvised and initiated co-composition, which expanded their range of body movement, shape, and timing. We asked them to draw with their bodies using movement impulse, engaging in the practice of psychophysical integration (Wait 2023), an intuitive improvisation between interoceptive processing and external stimuli. In this practice, participants attune so closely to the situation that action bypasses the mind's patterns and deliberations, allowing creative discoveries to emerge (fig. 2).

Figure 2_ Video still, psychophysical integration. Source: Photo by Mayerboeck.

The day culminated in a short co-creation exercise. Participants ventured to a nearby park, in silence, while maintaining their nested layers of somatic awareness and practicing their impulses for collaborative movement. Each gathered three objects from the park, which, after returning to the studio, they intuitively placed one after the other on the floor into a collective composition. Without verbal interaction, their bodily and spatial experiences gave form to a sculptural co-creation (fig. 3).

Figure 3_ Nonverbal co-creation. Source: Photo by Cranz.

Day 3. Co-Creational Action: The Body in Interaction with Others and the Environment

Day 3 culminated in a group co-design task, demonstrating how a heightened embodied awareness leads to resonance with others and translates into creative spatial practice. Framed by the Sensing Space methodology (Mayerboeck 2022, 2024), this day unfolded in three phases:

Phase 1: Individual and Collective Enactive Perception. The kinevisual practice encouraged fluid movement and group dynamics, challenging sensorimotor coordination through changes in speed, direction, and visual focus—balancing foveal and peripheral perception. Participants followed self-directed linear or curved pathways, guided by spatial rhythms and evolving swarm-like group dynamics. These interactions revealed shifting affordances and deepened attunement to others and the built environment, based on neuroarchitecture (Wang et al. 2022). More than a warm-up, this exercise built trust and social cohesion, making the resonant social dimension of space tangible. Concluding with stillness and a guided body scan, the movement practices reconnected inner sensation with outer spatial awareness.

Phase 2: Enactive Observation and Empathic Experience. Slow, deliberate walking into a narrower, furnished hallway with plants, seating, and textures transitioned participants from resonant motion awareness into spatial exploration through body-scale interactions (fig. 4). Using sight and touch, participants adopted various postures to nest within the environment. This prepared them for a partner with their eyes closed practice fostering empathy and trust. One participant guided the other with full-arm and hand contact, turning the guide's arm into a tactile "cursor" communicating pace, direction, and focus (figs. 5 to 7). Visual input was blocked, amplifying other senses for the partner with their eyes closed and emphasizing touch-based spatial communication for the guide. This was followed by a body-light practice in a fully darkened space. Lying on the floor, participants adjusted to the dark before exploring light's relationship to the body, revealing the ephemeral interplay between body and space through luminous sensation, such as using flashlights to see through the flesh and bones of one's hands.

Figure 4_ Spatial exploration through body-scale interactions. Source: Photo by Mayerboeck.

Figure 5 and 6_ Partners with their eyes closed exploring the space. Source: Photo by Mayerboeck.

Figure 7_ Partners with their eyes closed exploring the space. Source: Photo by Mayerboeck.

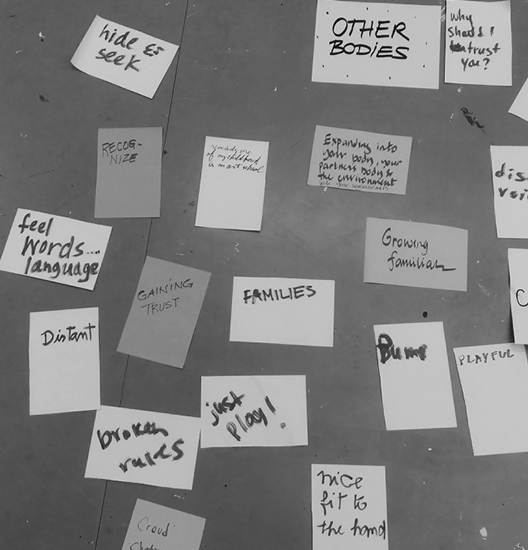

Phase 3: Individual and collective enactive reflection. Reflection began with autonomous writing, followed by participants placing Post-its describing their experiences directly where they occurred—in the foyer, hallway, and eyes closed routes. Participants then walked through these "collected stories" and sorted the notes into categories: Own Body, Other Bodies, and Built Environment (fig. 8).

Figure 8_ Post-its capturing individual spatial experiences. Source: Photo by Mayerboeck.

Finally, a verbally guided 15-minute imaginative journey of a "virtual architectural visit" with subtle acoustic cues invited exploration of a meaningful spatial context, blending body awareness with autobiographic memory. Participants then drew personal spatial storylines and shared these in small groups. The program concluded with a collective task: co-creating a joint storyline within each group. Materials and scale of realization were left open, fostering diverse design approaches. This phase sparked rapid ideation, resulting in unique "situated installations." The open format encouraged diverse expressions—some emphasized body conscious design (e.g., constructive rest), others introduced playful, multisensory installations with unexpected "somatic surprises" in a sensorial parcours (fig. 9).

Figure 9_ Participants spontaneously reconfigured lounge spaces into experiential installations. Source: Photo by Cranz.

Day 4: Reflection and Sharing

A fourth meeting brought our group together with five other workshop groups that had met simultaneously during the Moving Boundaries course, so that all participants could share their experiences. The comments by our participants were videotaped and transcribed verbatim, some quoted in this paper. One participant's reflection beautifully captures the essence of what we hoped to achieve:

yesterday we all talked [...] led through a beautiful, imaginative practice of inhabiting a space that we really connected with. And we spoke in our group [about] what others' experiences were. And it was really striking for me to see how everyone's experiences that they recounted […] within a built space or nature, it was really about how that environment brought them to the inner space, this sort of inner […] window to experience their being with a special sensitivity and even existential meaning that kind of changed how they perceived themselves. And I thought, that's what architecture is […] We just have to become more grounded and more emotional in the design process with these kinds of practices.

participant feedback and experiences

Participant feedback from day 4 was enthusiastically positive and emotional. Of the 20 enrolled participants, 14 participated in the entire course. Possibly, those who were not as enthusiastic did not come to the final session. We derived 14 themes from analyzing participant responses; 13 of the 14 were mentioned by more than one person: Beauty; Body Awareness; Co-creation; Connection with Others; Education of Architects; Enjoyment and Joy; Feelings and Feeling, including feeling space; Movement; Office Practice; Presence; Productivity; Reciprocity Between Self and Environment (a continuum between inside and outside); Trust; and Using Different Parts of the Brain Deliberately. Participant reviews indicate that they aspire to apply these experiences to their design practices around the world.

discussion and conclusion

As outlined above, several current initiatives explore how somatic practices can inform design. What distinguishes our approach is its layered progression—from interoception (awareness of internal bodily states), to proprioception (awareness of body position and movement), to interpersonal attunement and co-creation. This structured thematic arch enabled deeper integration of movement, perception, and co-design. Participants reported heightened bodily awareness, stronger interpersonal connections, and an expanded view of the possibilities of design. The experience showed that intuitive, somatically grounded processes can yield rich, meaningful outcomes—often more effectively than conventional, task-driven methods. Through embodied awareness, trust and empathy emerged not only as personal experiences, but also as essential components of the design process. Participants left with a renewed sense of the body as a source of knowledge, a creative partner, and a lens for reimagining spatial practices.

Our workshop structure posited a continuum of awareness beginning with the self, extending to others, and encompassing the environment. We explicitly aimed to foster this connection through layered somatic practices. Notably, the somatic perspective—though centered on internal experience—develops bodily attunement to a unified field bridging self, others, and the environment. As one participant exclaimed, "Being present with oneself allows one to be present in the world!", capturing this succinctly.

As practitioners experienced in conscious movement, we have encountered this continuum firsthand. Yet we approached it not as a universal outcome, but as an emergent possibility enabled by somatic methods. The consistent emergence of a felt sense of inside-outside interconnectedness among participants suggests that attending one's psychophysical state is a foundation for meaningful connection with others and the world.

future research

Incorporating somatic practices into architectural education and office practice is a next step mentioned by several participants. How might this be possible? Further research into integrating body awareness, movement, and health into architectural workplaces is warranted, given the multiple benefits reported by participants. Workshops developed from a protocol like the one we employed could become a regular part of the architectural creative process, enhancing co-design with users and the environment to improve existing design approaches. Somatic specialists could be hired as consultants to teach both employees and employers, until such practices are fully integrated into design pedagogy. Until then, we advocate for formal education in body awareness in all disciplines, especially architecture and other forms of environmental design.

bibliography

- Alexander, Zeynep Çelik. 2017. Kinaesthetic Knowing: Aesthetics, Epistemology, Modern Design. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Böhme, Gernot. 2017. "Atmosphere as the Fundamental Concept of a New Aesthetics." In The Aesthetics of Atmospheres, 23-36. Translated by Jean-Paul Thibau. New York: Routledge.

- Bruyère, Nathalie, Catherine Geel, and Victor Petit, eds. 2022. Global Tools (1973-1975): Éco-Design: Dé-Projet & Low-Tech. Toulouse: Institut Supérieur des Arts et du Design de Toulouse (IsdaT).

- Cranz, Galen. 2000. The Chair: Rethinking Culture, Body, and Design. New York: W.W. Norton.

- Cranz, Galen. 2017. "Rethinking the Chair and Sitting." In Sedentary Behavior and Health: Concepts, Assessments, and Interventions, edited by Weimo Zhu and Neville Owen, 45-54. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics.

- Cranz, Galen, and Leonardo Chiesi. 2014. "Design and Somatic Experience: Preliminary Findings Regarding Drawing Through Experiential Anatomy." Journal of Architectural and Planning Research 31 (4): 322-339. https://www.jstor.org/stable/44113090.

- Cranz, Galen, and Chelsea Rushton. 2024. "Body Conscious Design and Urbanism." Ekistics and The New Habitat 84 (2): 14-21. https://doi.org/10.53910/26531313-E2024842704.

- Dupuis, Aurélie. 2024. Architectural Rehearsal: Choreopolitical Ecologies within a Scripted World. Doctoral thesis, École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne.

- Ferreira, Maria da Piedade. 2021. "Corporeal Architecture: A Methodology to Teach Interior Design and Architecture with a Focus on Embodiment." In Handbook of Research on Methodologies for Design and Production Practices in Interior Architecture, edited by Ervin Garip and S. Banu Garip, 421-439. Media & Communications. Hershey, PA: IGI Global.

- Gálvez Pérez, María Auxiliadora. 2019. Espacio Somático. Cuerpos Múltiples. Madrid: Ediciones Asimétricas.

- Hanna, Thomas L. 1970. Bodies in Revolt: A Primer in Somatic Thinking. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston.

- Hanna, Thomas L. 1995. "What Is Somatics?" In Bone, Breath, and Gesture: Practices of Embodiment, edited by Don Hanlon Johnson, 341-353. Berkeley, CA: North Atlantic Books.

- Höök, Kristina, Sara Eriksson, Marie Louise Juul Søndergaard, Marianela Ciolfi Felice, Nadia Campo Woytuk, Ozgun Kilic Afsar, Vasiliki Tsaknaki, and Anna Ståhl. 2019. "Soma Design and Politics of the Body Addressing Conceptual Dichotomies through Somatic Engagement." In HttF '19: Proceedings of the Halfway to the Future Symposium 2019, edited by Joel E. Fischer and Sar. New York: ACM. DOI. https://dl.acm.org/doi/proceedings/10.1145/3363384.

- Leatherbarrow, David, and Mohsen Mostafavi. 2002. Surface Architecture. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Mallgrave, Harry Francis. 2010. The Architect's Brain: Neuroscience, Creativity, and Architecture. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

- Martin, Susanne, Christian Filk, and Lydia Schulze Heuling. 2021. "Dancing with Real Bodies: Dance Improvisation for Engineering, Science, and Architecture Students." In Algorithmic and Aesthetic Literacy: Emerging Transdisciplinary Explorations for the Digital Age, edited by Lydia Schulze Heuling and Christian Filk, 13-39. Opladen: Verlag Barbara Budrich.

- Mayerboeck, Veronika. 2022. Workshop "Sensing Space." Indoor and outdoor workshops at Moving Boundaries, Santiago and Porto, July 21-August 4. Side program of the conference.

- Mayerboeck, Veronika. 2024. "Sensing Space: Environmental Qualities and Human States." Body Matters, Proceedings of the Architectural Humanities Research Association (AHRA), 21st International Conference, Norwich University of the Arts, November 21-23, 2024. ISBN 978-1-0369-0451-7.

- Mayerboeck, Veronika, Kristina Höök, and Alé Duarte. In preparation. "Reflections on the Somatic Core of Ideation." Journal of Somaesthetics.

- Robinson, Sarah. 2020. "Resonant Bodies in Immersive Space." Architectural Design 90, (6): 28-35. DOI. https://doi.org/10.1002/ad.2628.

- Robinson, Sarah. 2021a. Architecture Is a Verb. New York: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group.

- Robinson, Sarah. 2021b. "Designing Movement, Modulating Mood." Dimensions: Journal of Architectural Knowledge 1 (2): 97-112. https://doi.org/10.14361/dak-2021-0209.

- Rose, Carina. 2025a. "Embodied Space: A Somatic and Movement Workshop for Architects." Paper and workshop presented at the Atmospheres and Architectonics Conference, Doctoral School of Moholy-Nagy University of Art and Design (MOME), Budapest, February 11-12.

- Rose, Carina. 2025b. "Skin, Somas and Scores: Experiential Movement Practices for the Architectural Process." Paper and workshop presented at the Uncommon Senses V: Sensing the Social, the Environmental, and Across the Arts and Sciences conference, Centre for Sensory Studies, Concordia University, Montreal, May 7–10.

- Sfligiotti, Silvia. 2021. "Why We Need More Somatic Culture in Design." In Design Culture(s) Cumulus Conference Proceedings Rome 2021 2: 4370-4382.

- Skrzypczak, Wiktor. 2021. "Principles of Somatic Movement Education for Architectural Design". Dimensions: Journal of Architectural Knowledge, 1 (2): 51-60. DOI. https://doi.org/10.14361/dak-2021-0205.

- Spatz, Ben. 2015. What a Body Can Do: Technique as Knowledge, Practice as Research. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Varela, Francisco J., Evan Thompson, and Eleanor Rosch. 1993. The Embodied Mind: Cognitive Science and Human Experience. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press.

- Vopel, Klaus W. 1994. Handbuch für GruppenleiterInnen. Zur Theorie und Praxis der Interaktionsspiele, 14th ed. Hamburg: Iskopress Verlag.

- Wait, Nalina. 2023. Improvised Dance: (In)Corporeal Knowledges. London: Routledge.

- Wang, Sheng, Guilherme Sanches de Oliveira, Zakaria Djebbara, and Klaus Gramann. 2022. "The Embodiment of Architectural Experience: A Methodological Perspective on Neuro-Architecture." Frontiers in Human Neuroscience 16: 833528. DOI. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2022.833528.