How to Cite: Quetglas, Josep. "Aeneas in Canaveses". Dearq no. 43 (2025): 18-23. DOI: https://doi.org/10.18389/dearq43.2025.03

How to Cite: Quetglas, Josep. "Aeneas in Canaveses". Dearq no. 43 (2025): 18-23. DOI: https://doi.org/10.18389/dearq43.2025.03

Josep Quetglas

Universidad Politécnica de Cataluña, Spain

The word and the gaze: what does someone who looks at a work and talks about it do? When someone stands in front of a painting, the page of a book, or an architectural or sectional drawing and talks about it, are they trying to reveal the truth behind that particular work? I think this person has a more humble role. They do not intend to discover or establish any truth, but rather resemble the person who, when gazing up at the clouds, says to their neighbor, "Look, that one looks like a giraffe." The only purpose of these provisional words is to make the other person pay more attention, to take a closer look at the cloud.

The person who looks and speaks is not talking about the work, but rather the gaze. It is an invitation to look. He describes himself as looking, and in doing so, invites the reader or listener to do the same: to become capable of seeing for themselves, to acquire eyes capable of truly looking around. He does not speak to hear his own voice, to issue a proclamation, or to construct a theory. His truth resides in something as unstable as the gaze, and its verification is simple: anyone who reads or listens can confirm for themselves whether they see the same thing. If so, the word has been effective; if not—if the word fails to leap from the page and take hold—it is as with the sower of words of whom Mark speaks.

To speak of the gaze is to fulfill the ancient rite of the Lord of Delphi, who neither speaks nor conceals, but gives signs.

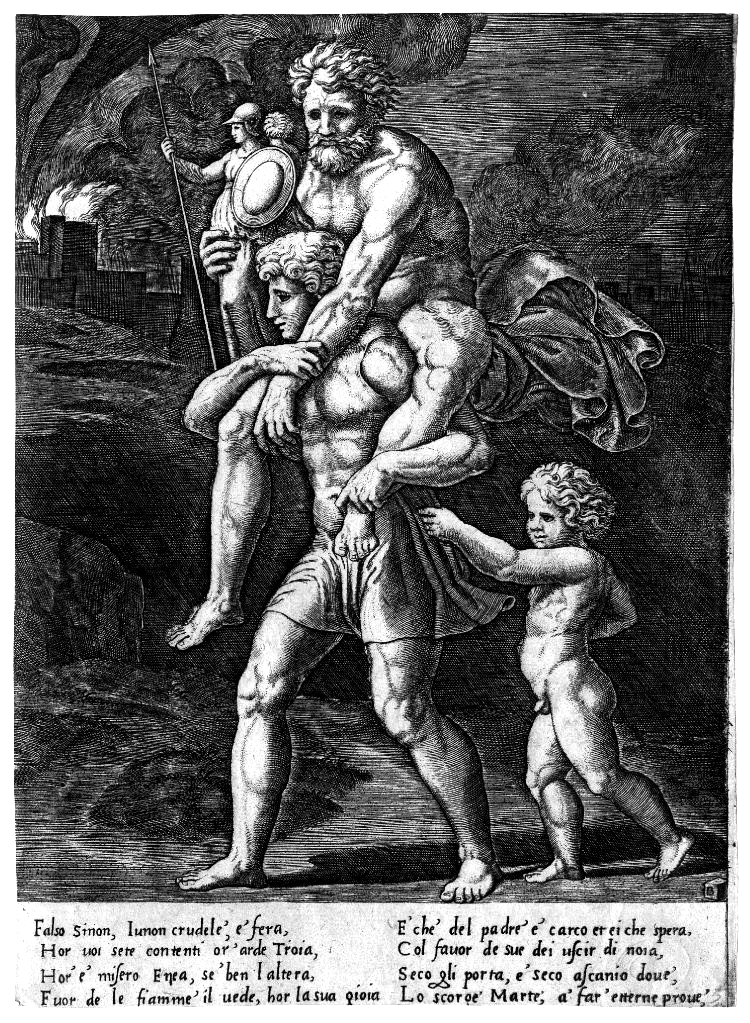

Figure 1_ Bernardo Daddi. Aeneas escaping from Troy, c. 1530

Troy burns, ravaged by the pillage of the victors.

The sacred objects—and his father, a venerable, sacred burden—the Cytherean hero carries upon his shoulders. Among so many and such great riches, the pious man has chosen this single treasure, along with his Ascanius (Metamorphoses, XIII, 624-627)

Aeneas—the Cytherean hero, the son of Venus—escapes the city and escapes death. He carries his aged father Anchises on his shoulders; he carries in his arms the sacred images that protected the city; and he holds his son Ascanius by the hand. He carries with him the past, the present, and the future. He carries his personal memory, the essence of his people, and a future that will no longer belong to him.

Perhaps bearing this threefold burden is the condition of any true work of art—or, indeed, of any human work—for every new creation not only opens itself as a promise, but also preserves the guarded presence of all that has come before.

"Nothing that has ever happened can be written off," wrote Walter Benjamin. For him, every new thing is accompanied by the redemption of all that has passed. His own words enact this principle, carrying with them the echo of words already spoken: ten years earlier, Freud had written, "Nothing disappears from what has ever existed," and "Nothing can vanish if, at some moment, it has been part of life."

In Civilization and its Discontents, Freud extends the thought with his description of Rome exfoliated in its strata—a passage that ought to be recommended, or quietly required, reading in the education of every architect.

Adam never existed; he is only a literary character. We cannot truly begin. There are no blank pages, and the hands of amnesia are bound. We always dig in furrows that others have plowed—whether to continue them, to divert them, or to cover them. Everything we do is done ritually, because it has been done before, and we do it again.

Each new work shelters something that must not disappear.

In every work of architecture there is always a narrative. Architecture is not a mere construction; it is not simply static resistance. The words of architecture are indeed construction, yet their arrangement follows not the logic of a dictionary, but that of a novel. Architecture carries time within itself, and the human form of time is memory—its other name: narration.

The dolmen tells the story of the transformation of the stone slab: so heavy, yet once it is hoisted, it frees itself from the pull of the earth, lifts its prow, stands on its own, and rises. The architecture of the dolmen expresses its will to become a menhir, to move from the horizontal on all fours to the vertical standing upright.

This is the origin of architecture. Architecture finds its first image in the awareness of weight, in the experience and sensation of gravity. But not according to the Roman principle of firmitas—valid only for construction—which is a receptive, passive principle. Architecture begins with gravity and sustains it, but only in order to compose it with its opposite. The opposite of construction, of firmitas, is not infirmitas, but rather, architecture itself. Architecture perceives and preserves gravity, yet it uses it to make lightness emerge.

Gravity and lightness are like night and day; each allows for and constructs the other. Architecture does not annul gravity but arises where gravity and lightness coincide—where each becomes the condition and culmination of the other.

If this definition of architecture is correct, then we should be able to confirm it in any true work of architecture, whether in the most complex or the most elementary.

For example, in the Portuguese Pavilion at the Lisbon Exhibition, where architecture is distilled to the pure manifestation of a lightened gravity, a suspended gravity. The Portuguese Pavilion is to architecture what Malevich's Black Square on a White Background was to painting: the zero degree, pure architectonicism. It is both the limit and the origin of all architecture—the morbid ambiguity, the Leonardesque smile—of a gravity that sustains itself. The roofs of Ronchamp and the Portuguese Pavilion—the only true Shroud in which to believe—are in complete accord.

Or, for example, how should one look at any of Siza's drawings of Christ on the cross? From the bottom up, or from the top down? Viewed from above, it is a defeated, inert body, held up only by the wrists. But when seen from below, it is Nijinsky rising onto the tips of his toes, arms lifted into the air as if taking flight. In Matisse's equivalent sculpture, there would be no ambiguity: the body collapses, overcome by its own weight. In Siza's case, however, the form conveys both sensations simultaneously, and the vitality of the form lies precisely in the presence of this duality. It is heavy and it ascends. It flies, yet it weighs—does it fly because it weighs?

I dare to suggest that the distinctiveness of Álvaro Siza's architecture lies in this particular sensation of gravity. The walls seem to float, while the light carries weight.

It is in this interplay that Siza's architecture evokes a sculptural quality—it is sculpture.

The interior of Ronchamp's chapel is organized according to a trapezoidal plan; yet for those inside, the divergence of the walls fosters the belief that the plan is rectangular. It is the same optical illusion—though reversed—found in Borromini's gallery at the Palazzo Spada in Rome, where the visitor perceives the corridor's length as extended.

In Ronchamp's "metaphysical" room, the floor is divided into two opposing halves: the left half is empty, while the right half is fully occupied by the wooden platform and benches. The left wall is white, irregular, and solid, its shadows and protrusions projecting into the room; the right wall, by contrast, is polychromatic, perforated, luminous, and honeycombed, with high-set ground-level openings that visually extend the interior toward the hillside outside.

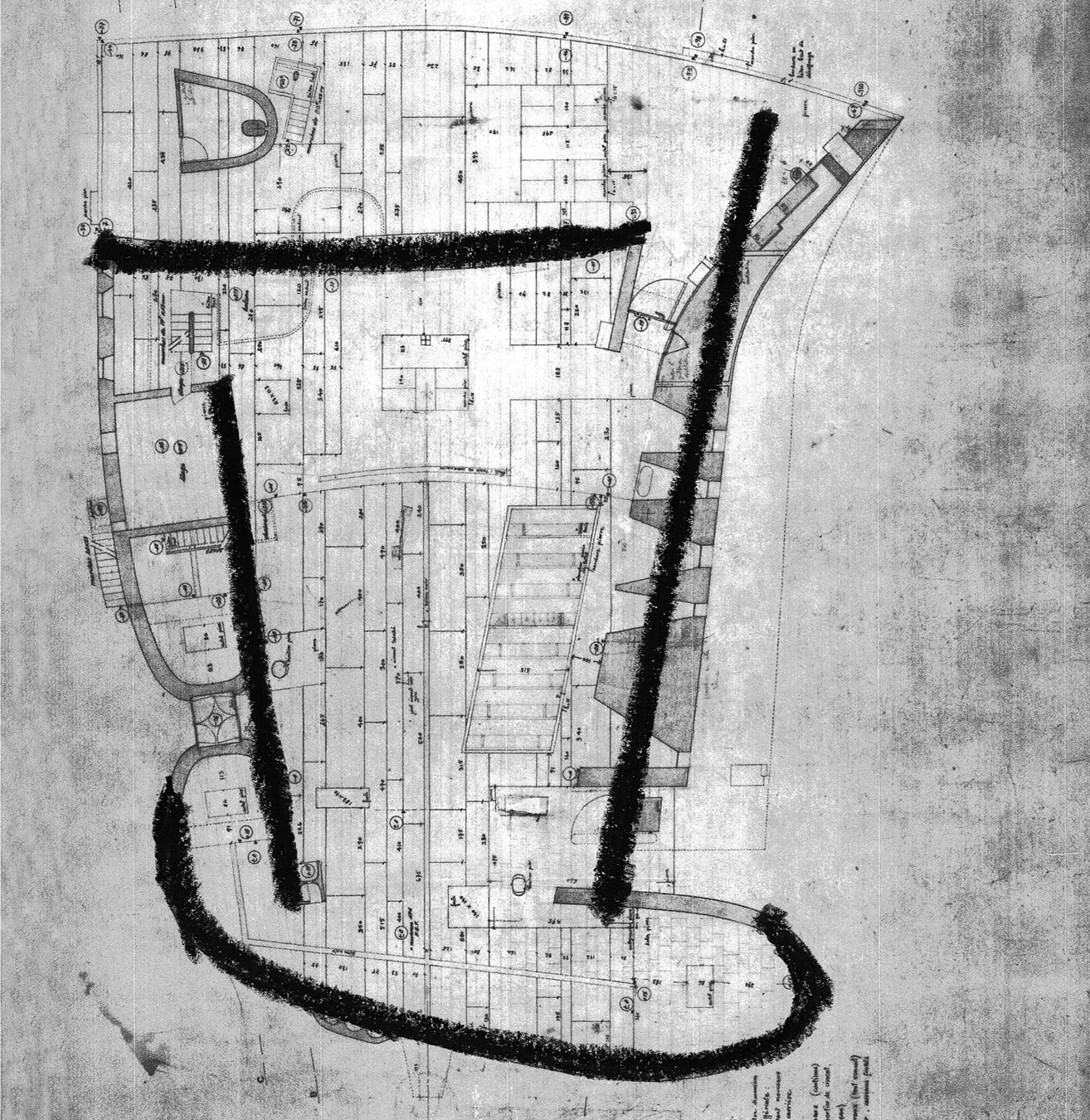

The four corners of the room have been carefully dissolved using contrasting techniques (fig. 2). On either side of the altar, vertical edges have been erased—shortening some walls and lengthening others—to disrupt the sense of a boxed enclosure. On the opposite side, the "Sack of Sins," the confessional, employs the inverse strategy: here, direct junctions are avoided by substituting cylindrical voids for the corners.

Figure 2_ Le Corbusier. Modified plan of the Notre-Dame du Haut Chapel, Ronchamp. © F.L.C. / ADAGP, [2025]

The entire composition of the chapel, from the smallest detail to the whole, operates according to this same principle of opposing symmetries. At this point, the visitor can begin to play on their own: all they need to do is identify one element and then search for its symmetrical opposite, which is not always immediately apparent.

Or one might try another exercise: to look at the Church of Santa Maria in Marco de Canaveses with eyes trained by looking at Ronchamp's work.

A rectangular box. We begin by erasing its four corners. On the altar wall, the corners disappear, hollowed out by cylinders that face one another in opposition: one does not touch the ground, remaining void; the other is solid and full. The fragments cut from these corners are not lost; they are transferred to the opposite side but, "on the other side of the mirror," are transformed into prismatic towers that extend the long walls and shorten the short wall. At our height, at eye level, there are no corners left. On one side, the floor of the room drops a step, descending into an interior—the baptismal font; on the opposite side, the floor rises and leaps outward into the hall—the choir.

The long walls also stand in opposition. One wall swells outward, encroaching into the interior of the room, while the wall opposite contracts until it aligns with its flat surface. The upper half of the domed wall is open, while its lower half remains closed; conversely, the upper half of the flat wall is sealed, while its lower half is fully opened by an uninterrupted window.

It is a meticulous system of counterpoints, with Ronchamp and Canaveses appearing as two rounds of the same game, played on different boards—a game that perhaps finds its prototype, or at least its most explicit essay, in Adolf Loos's house for Tristan Tzara.

The vertical line is the protagonist in Ronchamp's chapel—from the vertical-on-horizontal motif engraved in concrete that welcomes those who enter, to the horizontal-on-vertical composition in wood to the right of the main altar, and finally to the great vertical shaft of light in the southeast corner, which seems to draw the entire interior space in its wake.

Le Corbusier literally repeated this transition between horizontal and vertical on numerous other occasions.

For example, along the same south wall of the chapel, the wall drawn in the plan resembles a bull's horn or a crescent-shaped arch. It begins near the entrance as an enormously thick and inclined mass, like the wall of a pyramid, but gradually tapers and straightens until it loses all thickness, becoming a razor-sharp edge—an absolute vertical line. The south wall is, in essence, a flattened pyramid transformed into a vertical line.

But what, after all, is the architecture of the pyramid? It is an innumerable accumulation of stones, painstakingly stacked in strata that become increasingly inaccessible as they approach the summit. It would make little difference if we imagined it in reverse, as a spill of sand—stones at a different scale—beginning at the vertex, widening as gravity draws it to the ground. In fact, it is in this way, from the vertex downward, that Herodotus explains its construction—its cladding. We have been taught to see in the pyramid the very image of stability: the cult of mass, of skillfully and laboriously heaped matter, where the stone is as obedient to the laws of statistics as its builders were to the pharaoh.

But it is enough to stop looking at it from above—with the awareness that already knows its name and geometric figure—and to return to the primordial conditions of vision: to see it from the ground, like pilgrims who do not yet know the word pyramid, perceiving it for the first time, without recognition, after arriving on foot. What we then see is a vertical tower with no limit to its height, one that seems to have reached the sun, as revealed by the flashes of its golden apex.

As in a mirage, the sloping edges of the pyramid have risen upright; they have become the four vertical, parallel edges of an elongated tower—so tall that, like railroad tracks or the edges of a skyscraper, they converge at a vanishing point in infinity.

It takes only a slight etymological stretch to hear, within the word pyramid, the Greek word for fire or bonfire, pyr: the pyramid as a stone-fixed reproduction of a ritual fire, a sacrificial pyre whose smoke rises toward the sky.

Architecture is not a mere construction; it is the capacity to perceive transformation in what is built. In the architecture of the pyramid, for example, it is not a matter of alternately seeing one figure and then the other—the heap or the tower—replacing each other in turn. It is the ability to see both at once, in a single, simultaneous gaze. Perhaps only eyes trained to perceive in this way can truly see the architecture of Álvaro Siza.

Horizontal and vertical, mirrored: it is the very image of our own transformation, from quadrupeds to humans—of having stood upright and begun to walk.

A "continuous horizontal opening, 16 m compressed x 0.50 m high, with a sill 1.3 m above the floor, along the southeast side wall." This is how Siza describes the endless horizontal line—appearing as a window—that guides and sustains the human gaze through the room, at a height of 130 to 180 cm from the floor. Outside, this horizontal divides the wall in two: below, stone blocks; above, a white surface. "Here we celebrate clarity."2

Whoever passes through the 10-meter-high gate in Marco de Canaveses steps through a flash of light, becoming a vertical line themselves: they have stood upright, and they walk. "Here, beyond the death of the void, of loss, and of disaster."3

Come—as our common mother Lucy, who in her native Ethiopia is called Denkenesh, "the admirable," taught us—she who first set out on the African savannah, taking us by the hand, to flee from her burning Troy and to enter our own burning Troy, in this vast and terrible world.

For the young woman who inhabits the voice of Paula Abrunhosa.4

* This text was originally published in Spanish as: Quetglas, Josep. 2021. "Eneas en Canaveses". In A Casandra. Cuatro charlas sobre mirar y decir, 21–33. Madrid: Ediciones Asimétricas.

† Talk at the Serralves Museum in Porto, as part of the Conversations with History, The Alvaro Siza Talks, organized by Carles Muro, July 2018. The verses quoted in the previous paragraphs are from A casa de Deus, a 1990 poem by Sophia de Mello Breyner Andresen.

2 Original in Portuguese: Aquí celebramos a claridade.

3 Original in Portuguese: Aquí para além da morte da lacuna da perca e do desastre.

4 Original in Portuguese: Para a rapariga que habita na voz de Paula Abrunhosa.