Innovative Uses of Conventional Ceramic Materials and Climate Awareness. Contemporary Critical Regionalism Challenging the Modern Canon

Carlos L. Marcos

carlos.marcos@ua.es

Universidad de Alicante, España

Emanuela Lanzara

emanuela.lanzara@docenti.unisob.na.it

Università degli Studi Suor Orsola Benincasa di Napoli, Italia

Mara Capone

mara.capone@unina.it

Università degli Studi di Napoli Federico II, Italia

Received: September 30, 2022 | Accepted: April 10, 2023

Recent decades, have witnessed an emergence in the alternative use of ceramic materials in architectures designed with phenomenological sensitivity. This has implied rethinking materials and form, and an understanding of place that considers climate actively. This article analyses climate-conscious ways of using brick or other ceramic materials as enclosures that overwrite traditional applications and construction systems. These materials are transformed into skins and filters that provide protection from the sun while allowing natural ventilation and light. Applications employing the most advanced technology follow a computational logic characterised by digital disruption.

Keywords: ceramics, climate awareness, contemporary architecture, disruption, digital consciousness

Figure 1_ Bearth and Deplazes (Facade design by Gramazio and Kohler), Gantenbein Winery, 2006. (Courtesy of Bearth & Deplazes Architects).

introduction. ceramics and materiality

Throughout history, architects have found solutions for functional, structural, economic and environmental sustainability, designing forms that are at once efficient and expressive. It is important to recognize, however, that over the last century, the construction industry has become one of the most resource-intensive and environmentally damaging human activities.

This study presents new approaches in conceptualizing and materializing architectural design using ceramics, a material with ancient origins. These applications focus on contemporary materiality while consciously responding to climate challenges. In order to understand this transformational approach in the use of a traditional construction material, we will provide a brief history of the uses of ceramics.

Bricks have been an inexpensive material used for millennia. Easy to lay and to handle, they are ideal for building walls and vaults, two of the most fundamental elements of construction to provide enclosure and support. People were already sun-drying bricks and even firing them in kilns thousands of years before the Romans universalised their use.1 Torroja (1998, 34) proposes that bricks are the first man-made material conceived through the mastery of Empedocles' four elements: water, air, earth and fire. Due to their resistance, hardness and durability, bricks are a versatile material and highly suitable for construction purposes. In ancient Rome, bricks were used for the structure of walls and vaults which were then veneered with marble and other limestones. This was because bricks were considered to lack the nobility of stone, and so they perverted the purity of Hellenic architecture which was characterized by solid stone elements. It marked the beginning of a tradition which was criticized by Loos during the early modernism2. Ancient Romans also used brick bonding techniques to enhance the strength of brick structures. Brickwork fulfilled both structural and constructive functions, and was often used as formwork for the pouring and curing of mass concrete. The idea of material continuity went hand in hand with the notion of stereotomic continuum (Aparicio 2006, 17). This guaranteed the transmission of compressive loads while simultaneously integrating structural and enclosure tasks within a single construction piece.

The idea of bonding masonry gave rise to a whole theory of brickwork: from the basic Flemish bond —already used by the Romans— to much more elaborate combinations depending on the thickness of the walls. By employing bricks as a visible enclosure, different types of constructive bonding types were transformed into distinct textures. Eventually, these textures became an integral feature of the façade itself, as can be observed in the iconic neo-Mudejar style. Brickwork, as an architectural technique, has evolved very little in terms of construction technology over the centuries. Consequently, the different structural types that employ it have also changed little (Torroja 1998). One of the other most popular uses of ceramic materials is tile roofing. This practice is almost as old as the use of brick itself, and has consistently been one of the most widely used roofing materials.

With the advent of modernity, reinforced concrete, steel, and glass brought substantial changes to construction technology and called into question the usefulness and function of ceramic materials. The breakdown of building design into skeleton and skin constituted the most significant of the changes being introduced into the tectonic syntax of modern architecture (Frampton 2001). It also freed brick from its primary function of load-bearing, and it became more commonly used for enclosures or, in the case of hollow bricks, for partitioning. Modern projects in which brick retains its load-bearing functions are rare. One of the few examples of this is Mies, who employed brick for this purpose in residential architecture in his European period (Matos and Castillo 2011). Perhaps one of the most memorable examples is Mies' legendary brick house project from 1924, considered by some to be more influential than many of his other works that were actually built.3 Mies used brick walls as non-structural enclosures during his American period (for example, in some of his buildings for the ITT). This aligns with the progressive refinement of construction methods in his work. Other Modern masters also used brick in different ways in their designs, such as Wright, Le Corbusier and Aalto, to name but a few.

Modern architecture found its most popular embodiment in the so-called international style (Hitchcock and Johnson 1932). This style was so successful in such a short period of time that it soon became the aesthetic standard in many parts of the world. In the mid-twentieth century, it became clear that the universalisation of one architectural language was impractical considering the significant climate contrasts and diverse socio-cultural roots of different countries. This led to the emergence of critical regionalism and its diverse responses to the Eurocentric homogeneity of the international style. This movement did not necessarily imply a return to the vernacular, but rather a conscious reinterpretation of modernity in the local context (Frampton 1983).

In recent decades, there has been a growing awareness of the problems that local climate and culture pose to the architect. Consequently, some architects are beginning to work with greater climate awareness and a more sensible approach that considers the environment in which their design will operate. Surprisingly, despite globalisation and the internationalisation of the work of many architectural firms, there is a notable presence of local accents and an emphasis on environmental concerns in much of this recent activity. This paper analyses several examples in which ceramic materials play a leading role in relation to these trends of recent years.

methodology

Our research selects a series of contemporary architectural works which include unconventional applications of ceramic materials. These designs also align with climate awareness in order to address the new challenges in twenty first century construction. The cases were selected for their sustainability, as well as for their form, which needed to be compatible with contemporary architectural language. Accordingly, the specific disciplinary implications of these case studies are analysed and discussed.

It is important to present an initial methodological consideration. Constraints on the length of the article have implied a reduced number of cases discussed in it. This inevitably limits the scope of possible classification categories. Conscious of this, we have proposed three dimensions for consideration: first, the phenomenological aspects of the solutions adopted; second, sustainability features that could be associated with a new critical regionalism; and third, technological solutions to be analysed in the context of contemporary technological culture in architecture.

The research focuses on the extent and manner in which architects can foster innovation through their use of ceramic materials, responding to changes that are not purely material in nature. For example, what are their proposals for more sustainable habitation that promotes environmental awareness or that responds to the challenges posed by the evolution of climate. We also wish to explore the way architecture has been adapted to local geographical and cultural contexts and specificities.

Certainly, there are many architectural approaches that adhere to these criteria, but they may not explore them through the use of ceramic materials, which is why they fall outside of the scope of our study. Part of the work of the research was selecting examples that respond to our classification criteria, but that do not generally conform to the "glossy" standards of trendy architectural journals and therefore may not have received much academic or media attention, thus remaining "off the radar".

ceramics employed climate-consciously as a porous skin in contemporary architecture

Lattices: reinterpreting local culture

Modernity played a pivotal role in establishing a real distinction between structure and enclosure by dismembering the stereotomic continuum of load-bearing walls and vaults. The notion of enclosure, and of the façade especially, as a lightweight element almost resembling textiles, is strongly influenced by Semper's theories on the division between tectonic and stereotomic conceptions of architecture (Semper, Mallgrave and Robinson 2004). It is also connected to the distinction between light enclosures and load-bearing walls in vernacular German architecture. As Frampton has explained, "die Wand" indicates "a screen like partition such as we find in wattle and daub infill construction", while "die Mauer" refers to "a massive fortification" (Frampton 2001, 5). Semper further distinguished between tectonic function and the wall as an enclosure, which he argued had originated as a textile. In his important work on the concept of style, Semper conducted extensive research to establish connections between the decorative arts and the foundational crafts of architecture. Thus, he ascribed a textile-like quality to the walls in their functions of enclosure and shelter, drawing a connection to the craftsmanship of tapestry and tapestry-making (Semper, Mallgrave and Robinson 2004).

Passive systems such as forced ventilation, the solar chimney effect, thermal insulation, greenhouses, solid walls, Trombe walls, wind towers, or ventilated facades are different approaches to the same final goal of indoor comfort achieved without energy consumption (Al-Shamkhee et al. 2022). Passive technologies are more sustainable than active ones, and find in the geometric configuration the optimization of structural and environmental performance. In the Hawa Mahal in Jaipur (India), also called "The Palace of the Wind", which was designed by Lal Chand Ustad, the latticed façade, carefully and elaborately carved out of red sandstone, allows for the circulation of fresh air by means of Venturi's effect. Although it was initially designed as a privacy screen allowing those inside to look out without being seen, it serves as a paradigmatic example of how these skins can provide protection from the sun by allowing natural ventilation and visual permeability. It is an early example of façade design which seeks to incorporate the properties of textiles or even of skin.

Figure 2_ Sanuki Daisuke architects. House in Binh Thanh, 2016 (main façade and inner courtyard). (Sanuki Daisuke Architects photograph by Hiroyuki Oki; courtesy of Hiroyuki Oki).

Frampton's critical regionalism holds a central place in the debate on globalisation and actually anticipates it to some extent in the field of architecture. Frampton attempts to respond to the paradox of the polarisation between tradition and modernity, exploring how to be modern by returning to our origins, or in other words, how to revive a vernacular local culture in order to integrate it into universal civilisation (Frampton 1983, 148). In this way, Frampton's intellectual stance involves the synthesis of two implicit philosophical traditions, phenomenology and critical thinking, establishing "a constructive dialogue between Habermas' 'modern project' and Heidegger's insistence on 'being as becoming'" (Reza Shirazi 2018).

Figure 3_ Sanuki Daisuke architects. Dwelling in Binh Thanh, 2016 (ground floor, first floor and longitudinal section). (Courtesy of Sanuki Daisuke Architects).

In 2016, Sanuki Daisuke built a house between party walls in the town of Ho Chi Minh (Vietnam), designing the façade based on local tradition (Figs. 2 and 3). The façade was built using low-cost extruded ceramic blocks which allow for natural ventilation while forming a decorative latticed screen that filters sunlight. The design skilfully combines several rows of different block types with varied geometric patterns which are supported by load-bearing joists of reinforced concrete (Fig. 2). Daisuke acknowledges that it was the client who requested him to use this type of material because of its low cost and local popularity. Daisuke used other ceramic elements in the project for parts of the flooring and the cladding, taking advantage of their material qualities. Chromatic and textural accents that contrast with the continuous white coating of the walls are all part of the architect's expressive intentions, as can be observed in the perspective section view (Fig. 4).

Figure 4_ Sanuki Daisuke architects. Dwelling in Binh Thanh, 2016, (perspective section view, relationship with lanai space). (Courtesy of Sanuki Daisuke Architects).

The benign climate allowed the integration of a contemporary reinterpretation of the lanai, as Daisuke explained (Sanuki Daisuke Architects 2016), which is a covered but open space serving as a transition between interior and exterior spaces. This characteristic element of Hawaiian architecture has also become popular in this part of Southeast Asia; it was Ossipoff who popularised its modern reinterpretation (Sakamoto and Britton 2008, 69). Daisuke's use of these design elements achieves a controlled visual permeability, and degrees of privacy and cross-ventilation between the two towers and the patio that separates them. Thus, he manages to overcome the problem of the party walls which divide the property from its neighbours, while adapting to the conditions of the site with a sectional solution that is inspired by local tradition and shows real climate awareness.

Another Vietnamese architectural practice known for employing bioclimatic sensibility in its projects, Vo Trong Nghia Architects, has employed a similar solution for a house in Bat Trang, near Hanoi, a town famous for its ceramic craftsmanship (Figs. 5, 6 and 7). Following the local tradition of workshop dwellings in which craftsmen live, work and sell their products, a complex hybrid programme was designed. The family sells their handicrafts on the two lower floors, leaving the upper floors for the housing programme. In this case, the main façade of the house comprises an expansive ceramic latticed skin that the architects commissioned from local craftsmen, creating a space between the lattice and house itself which is filled with vegetation. This created a deep façade in three layers (ceramic lattice, vegetation, and glazing) which also communicates the architectural image of the house to the surrounding city (Vo Trong Nghia Architects 2021, 51) (Fig. 7). The sectioned nature of the design shows the relationship between the more compact programme of the living spaces, the skin that surrounds them, the interstitial spaces filled with vegetation and the rooms connected to them (Fig. 5).

Figure 5_ Vo Trong Nghia Architects, House in Bat Trang, 2021, (elevation and cross-section). (Courtesy of Vo Trong Nghia Architects).

In this case, openings of different sizes that allow the luxuriant vegetation to emerge interact with the smaller gaps in the ceramic block grid that constitute the actual latticework. The shade produced by the two layers allow for large glazed openings protected from the sun. It is clear that the mild climate fosters these types of architectural proposals as well as the dissolving of boundaries between interior and exterior spaces (Fig. 6 and 7).

Figure 6_ Vo Trong Nghia Architects, House in Bat Trang, 2021, (spaces between skins with vegetation). (Vo Trong Nghia Architects, photograph by Hiroyuki Oki; courtesy of Hiroyuki Oki).

The use of these types of designs in domestic architecture should not lead us to believe that they cannot be implemented in the realm of public buildings too. The same architectural firm used similar principles for the showroom of the electronics company Panasonic, in a building called The Lantern (Fig. 8) in the Vietnamese capital Hanoi (Vo Trong Nghia Architects 2016).

Figure 7_ Vo Trong Nghia Architects, House in Bat Trang, 2021, (2nd and 5th floors, and building in urban context). (Vo Trong Nghia Architects, photograph by Hiroyuki Oki; courtesy of Hiroyuki Oki).

In all these examples, an important phenomenological component is introduced by the way light is filtered through these lattices. The way in which light diffuses over the building's surfaces, and is reflected or filtered by them, has an enormous capacity to create different atmospheres. This is a hallmark of Zumthor's architecture, who has said that, like other of his peers, he chooses materials by observing how they catch or reflect light (Zumthor 2006, 59). As Guitart explains in his monograph on architectural filters, the design of these elements has evolved over time. Filters create meaning, they mediate between interior and exterior spaces, as well as between the light outside and how it is perceived by those inside, and so they add a phenomenological dimension to architecture (Guitart 2022, 265). Pallasmaa conceives architecture as "the art of reconciliation between ourselves and the world, and this mediation takes place through the senses" (Pallasmaa 2005, 72).

The examples analysed here incorporate filters of a certain thickness that, in addition to guaranteeing that memorable experience of architecture to which Pallasmaa refers, provide greater indoor comfort in latitudes where uncontrolled entry of the sun's rays implies a significant thermal gain. The designs analysed above integrate the vernacular in a simple yet contemporary language, without incorporating sophisticated technologies. This use of ceramic lattices as passive low-cost constructive systems constitutes an example of contemporary climatic consciousness. These lattices are imbued with both a phenomenological dimension and a climatic sensitivity that operates within a more sustainable paradigm.

Figure 8_ Vo Trong Nghia Architects, The Lantern, Hanoi, 2016, (lattice detail, building view in context). (Vo Trong Nghia Architects, photograph by Hiroyuki Oki; courtesy of Hiroyuki Oki).

filters: architectural disruption and computational logic

The growing technification of architectural design has also engendered other more disruptive approaches that seek to establish new symbiotic relationships between ceramics and technology in the contemporary discipline.

In the year 2000, Atelier Objectile, with a project led by Bernard Cache, produced a series of designs in which this textile-like quality, previously anticipated by Semper, found a contemporary materialisation using digital technologies. Cache proposed a critical reinterpretation of Semper that combined digital and constructive technologies, thereby assimilating the concept of "material transposition" (stoffwechsel). This is a notion which stresses the technological and material origins of architecture, while pushing for their renewal through the irruption of the digital revolution and computational logics (Cache 2000).

Despite the reluctance of many architects and some critics to recognize the value of this revolution in progress triggered by information technology, it must be acknowledged that some of the most radical, innovative approaches in recent years have been associated with the intentional use of these technologies in the context of a digital culture in architecture (Picon 2010). In 2013, Mario Carpo, one of the most influential authors in this field of research, published a compilation of texts written over the previous two decades on the paradigm shift brought about by digital tools under the title The Digital Turn in Architecture 1992-2012 (Carpo 2013).

Extrapolating to the field of architecture the idea of technological disruption coined by Bower and Christensen (1995) in the business world, we use the word 'disruption' here to mean those innovative and radical transformations in the language of architecture that manage to embody the technological zeitgeist of their time, redefining an aesthetic, conceptual and constructive framework that succeeds in replacing the pre-established canon. By the standards of this approach, architectural modernity was one of the most disruptive transformations in history. New materials and construction systems, together with a profound aesthetic change —promoted by the avant-garde movements of the 20th century—, completely replaced the established canon, laying the foundations for the establishment of a new modern ideal, a certain international style.

In the 1990s, when digital tools started to become widespread in architectural studios, the expansion of the limits of representation and with them the possibilities to conceive new designs opened a kind of Pandora's Box in relation to architectural form.4 Thus, architects such as Eisenman and Gehry, and the generation that followed them who were more familiar with these tools, began to explore a new formal repertoire. The first of these was situated in the realm of deconstruction, the second in operations of speculation on form linked to formlessness. The architecture of the so-called blobs represented an incarnation of ideals in which temporality and the dynamic permeated the emerging virtual architecture (Lynn 1999). It was fostered by control over form facilitated by these new technologies and which had previously been tested in other industries such as aeronautics and shipbuilding (Kolarevic 2003). Until the Guggenheim in Bilbao was built, these projects were no more than architecture on paper. However, architectural form does not adapt to function in the way that the fuselage of an aeroplane or the hull of a ship does. In architecture, the form of the container is, to a large extent, arbitrary (Moneo 2005). To be more precise, it is not predetermined by the laws of physics, although it is determined by them. In other words, through their manipulation of form, the architect has a range of expressive possibilities not available to the engineer.

True digital disruption in architecture implies a distinctly digital consciousness: the intentional use of new technologies to achieve architectures that would not be possible without them (Marcos, Capone and Lanzara 2017). As Mario Carpo has pointed out, the second digital turn involves a computational logic, with computers capable of processing millions of data per second and working on the scale of so-called big data (Carpo 2017).5

CAD-CAM convergence applied to architecture raises new ways of approaching materiality, which some have referred to as new materiality, alluding to the technological transformation in the use of building materials (Picon 2004). In fact, as Picon himself admits, one of the features that characterises the discourse linked to this digital revolution is the awareness of a new materiality. That is to say, a dynamic conception of matter that defies the limits of hylomorphism and, to a certain extent, defines the disruptive limits discussed by Achim Menges or Jenny Sabin under the notion of material computation (Picon 2019).

An example of how this new approach to materiality is manifested in the field of digital innovation using ceramic materials is the pioneering research conducted by Gramazio and Kohler in their workshop entitled The Informed Wall at the ETH in Zurich (Bonwetsch et al. 2006). Their aim was to explore the possibilities in bricklaying provided by digital fabrication robots. This is where the computational logic that we highlighted above becomes fully evident. Producing a 3D model by hand for every single brick in a double-curvature wall would be too laborious. Moreover, laying each brick to construct such a wall would be unthinkable through conventional means. Not, however, with computational logic and customised mass production systems. Programming the model with a simple computer script is an easy task for those familiar with software coding. For the robot, it makes no difference whether every brick is plumb across a single plane or if each brick occupies a distinct position in space with its own relative rotation. The robot is able to build the curved wall with complete precision in a timely manner (Fig. 9).6

Figure 9_ Fabio Gramazio and Matthias Kohler, Informed Wall workshop. ETH, Zurich, 2006. (Courtesy of Gramazio&Kohler Architects).

Complexity and irregularity are hallmarks of digital design. They take centre stage when computers offer the added advantage of controlling vast amounts of information with a singular precision that renders them irreplaceable for such tasks. Digital design is achieved through programming, rather than the design of form itself through form finding strategies, which Carpo (2017) refers to as form-searching. This advancement is also indebted to CAD-CAM convergence which enables the direct integration of information into processes of conception and materialisation of architecture, a process others have referred to as informing architecture (Bonwetsch et al. 2006, 489).

Thanks to this approach developed in the workshops at the ETH Zurich, in 2006 Gramazio and Kohler were invited to collaborate on the design of the façade of the Gantenbein winery in Switzerland with Bearth and Deplazes (Figs. 1 and 10). The container of the grape fermentation space was conceived as a large basket full of grapes. Seen from afar, the façade looks like a silkscreen with this somewhat literally figurative and arguable image as an articulating central element of the façade. The precise positioning of each brick in the wall (totalling tens of thousands of bricks, each with its own position and orientation in the space), evidences a sort of big data processing on the scale of the wall, allowing the form of the enclosure to be constructed in ways hitherto unimaginable. The innovative approach to brickwork, a traditional building material, owes its success to the utilization of robots.

This cutting-edge approach to a traditional building material such as brickwork has managed to achieve a new materiality which would have been unattainable without the use of robots. From the interior, the aesthetic potential of the brickwork paired with the irregularity of computational design can be observed. The walls produce captivating light effects and allow the interior to be permeated with fresh mountain air. The overall impression achieves a phenomenological sensibility reminiscent of the work of Swiss master Peter Zumthor (Afsari, Swarts and Russell 2014).

Figure 10_ Bearth and Deplazes (Facade design Gramazio and Kohler), Gantenbein Winery, 2006. (Courtesy of Bearth & Deplazes Architects).

Another example of the harnessing of this computational logic for assisted design and manufacturing applications, this time in the field of research and experimentation, is the Terra-Cotta Grotto prototype (Garofalo, Guitart and Kahn 2020). It uses perforated terra-cotta rain screen panels with complex geometries and folds obtained by waterjet cutting. The researchers have reported temperature differences of between 5° and 10° Fahrenheit (2.8 and 5.6 ºC) between the radiated outer surface and the inner face of the wall. This research demonstrates the role that ceramics and new technologies can play in improving energy efficiency.

Another case study that illustrates how computational logic and new critical regionalism (Marcos and McCormick 2021) can be applied to ceramic skins can be found in the work of A.P.P. Architects, in a design called Revolving Bricks Serai, in Arak (Iran) (Fig. 11). The entire façade of the building is screened by a large privacy lattice that protects the building from the harsh sun typical of the local climate. It once again features irregular shapes, which here are arranged in an undulating motion to pull the façade together as a whole. In this design, the individual bricks are bonded to a metal frame which means that an even greater twist can be achieved in the brickwork, and so that it can be understood as a literal skin.

Figure 11_ A.P.P. Architects, Revolving Bricks Serai, 2015. Arak, (Markazi province, Iran). (Courtesy of Farhad Mirzaie A.P.P. Architects).

As a result, the façade is appreciably more transparent than that of Gantenbein's winery, presenting an apparently contradictory image. We tend to imagine a masonry façade as opaque, rigid and lacking visual permeability, but the use of new technologies proposes a new materiality of brick that challenges the conceptions we normally attribute to this ceramic material. In a sense, this façade treatment can be understood as a reinterpretation of the fabulous lattices in the architecture of the Mughal Empire, for example in the Red Fort in Delhi. These lattices use the principle of the subtraction of material to achieve the effect of transparency, creating introspective atmospheres by means of stereotomic filters through which "punctual, contained and directed" light can pass (Guitart 2011, 57).

Figure 12_ A.P.P. Architects, Revolving Bricks Serai, 2015. Arak, Markazi province, Iran (detail brickwork and colour patterns, building in context). (Courtesy of Farhad Mirzaie, A.P.P. Architects).

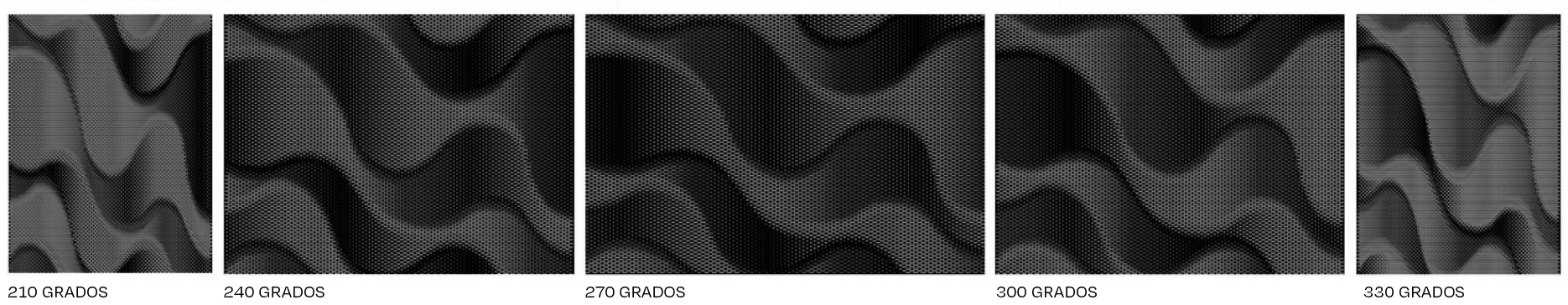

The visual permeability in the façade designed by A.P.P. Architects is achieved through the complex rigging and precise positioning of each individual brick. In the Mughal fortress, the same effect is attained by the meticulous work of stonemasons on the red sandstone typical of this architecture. The artisans remove material in a technique more akin to goldsmithing than to stonemasonry, with a skill that even today is astonishing to behold. The phenomenological effects achieved in both cases through the filtering of light share certain parallels, but each uses substantially different technologies. Manual production through craftsmanship (Sennet 2009) is replaced by machinic computational design that can define the position and orientation of each individual brick to execute this complex skin, inconceivable without these new technologies. Moreover, digital tools can also be used to simulate various aspects and considerations related to design enhancement, what is known as performance-based design. They can even anticipate the visual effects generated by algorithmically-defined geometries, such as for the façade of rotated bricks in the A.P.P. design (Fig. 13). This careful planning of the visual impact was crucial for this particular case, as the ends of the bricks were painted cobalt blue and turquoise, their different rotations revealing their colours, which resulted in the undulating effect and chromatic gradations of the façade.

Figure 13_ A.P.P. Architects, Revolving Bricks Serai, 2015. (Simulation of the optical effects of the façade patterns which depend on the angle from which a person observes the façade). (Courtesy of Farhad Mirzaie, A.P.P. Architects).

conclusions

This discussion has revealed the possibilities for exploring the materiality of ceramics in architecture, even when using traditional elements such as bricks or ceramic blocks. Using traditional materials does not preclude the possibility of designing more environmentally sensitive architecture. This can be achieved by incorporating passive solutions that are much more eco-sustainable than complex air-conditioning systems that consume energy, produce a larger carbon footprint and are more difficult to maintain. Often, the use of A/C compensates design that is inadequate for a given location due to, for instance, the use of construction systems or aesthetics more appropriate for other latitudes.

Complete climate awareness implies the use of building strategies and materials to minimise architecture's climate footprint or the excessive consumption of either material resources or energy. Sometimes, reinterpreting traditional building systems or materials such as ceramic blocks or bricks can change the role which they have conventionally been attributed.

Computational logic opens up a new world of possibilities for form which, when approached with a true digital consciousness, can foster innovation in the use of ceramic elements even as old as brick. Irregularity and complexity are hallmarks of computational design, and are plainly manifested in these types of projects.

Some of the architecture explored here has shown the potential of digital disruption applied to ceramics that explores a new approach to ceramic materiality in architecture. That is, the understanding of a new materiality that emerges from the innovative way in which architecture is conceived, designed and fabricated, a process which has characterised the so-called second digital turn. It is important to remember that the logic that illuminates disruptive solutions in architecture could not be conceived or materialised without the conscious and intentional use of the possibilities stemming from CAD-CAM convergence.

The evolution of climate together with demographic challenges need a shift in architectural sensibility towards adaptation to climate and local traditions as well as the use of passive systems that reduce the carbon footprint and energy consumption of the built environment. The examples analysed here show that this sensitivity is perfectly compatible with innovation, contemporary aesthetic languages and an architecture capable of generating memorable experiences.

references

- Afsari, Kereshmeh, Matthew Swarts and Russell Gentry. 2014. "Integrated Generative Technique for Interactive Design of Brickworks". Journal of Information Technology in Construction (ITcon) 19: 225-247. http://www.itcon.org/2014/13

- Al-Shamkhee, Dhafer, Anwer Basim Al-Aasam, Ali H. A. Al-Waeli, Ghaith Yahay Abusaibaa and Hazim Moria. 2022. "Passive Cooling Techniques for Ventilation: An Updated Review". Renewable Energy and Environmental Sustainability, 7, no. 23. https://doi.org/10.1051/rees/2022011

- Aparicio Guisado, Jesus María. 2006. El muro: Concepto esencial en el proyecto arquitectónico; la materialización de la idea y la idealización de la materia. Madrid: Biblioteca Nueva.

- Bafna, Sonit. 2008. "How Architectural Drawings Work-and What that Implies for the Role of Representation in Architecture". The Journal of Architecture, 13, no. 5: 535-564. https://doi.org/10.1080/13602360802453327

- Bonwetsch, Tobias, Daniel Kobel, Fabio Gramazio and Matthias Kholer. 2006. "The Informed Wall: Applying Additive Digital Fabrication Techniques on Architecture". In Synthetic Landscapes. Proceedings ACADIA 2006, edited by Gregory A. Luhan, Phillip Anzalone, Mark Cabrinha and Cory Clarke, 489-495. Louiseville, KY: University of Kentucky/Association for Computer Aided Design in Architecture (ACADIA).

- Bower, Joseph L., and Clayton M. Christensen. 1995. "Disruptive Technologies: Catching the Wave". Harvard Business Review 73, no. 1: 43-53.

- Cache, Bernard. 2000. "Digital Semper". In Anymore, edited by Cynthia Davidson, 190-197. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Carpo, Mario. 2013. The Digital Turn in Architecture 1992-2012. Chichester: Wiley.

- Carpo, Mario. 2017. The Second Digital Turn: Design Beyond Intelligence. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Frampton, Kenneth. 1983. "Prospects for a Critical Regionalism". Perspecta, 20: 147-162.

- Frampton, Kenneth. 2001. Studies in Tectonic Culture: The Poetics of Construction in Nineteenth and Twentieth Century Architecture. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Garofalo, Laura B., Miguel Guitart and Omar Khan. 2020. "Porous Mass: Terra-Cotta Redefined Through Advanced Fabrication". TAD, 4, no. 2: 232-241. https://doi.org/10.1080/24751448.2020.1804767

- Guitart, Miguel. 2011. "Estrategias estructurales en los filtros cerámicos". In Ensayos sobre arquitectura y cerámica (IV), edited by Jesús Aparicio Guisado and Héctor Fernández Elorza, 53-64. Madrid: Mairea Libros.

- Guitart, Miguel. 2022. Behind Architectural Filters: Phenomena of Interference. New York: Routledge.

- Hitchcock, Henry-Russell, and Philip Johnson. 1932. The International Style: Architecture since 1922. New York: W. W. Norton & Company.

- Kolarevic, Branko. 2003. "Information Master Builders". In Architecture in the Digital Age: Design and Manufacturing, edited by Branko Kolarevic, 57-62. New York: Spon Press.

- Loos, Adolf. 2019. "The Principle of Cladding". In Ornament and Crime. Translated by Shaun Whiteside. New York: Penguin Classics. Ebook. First published in 1898 in Neue Freie Press.

- Lynn, Greg. 1999. Animate Form. New York: Princeton Architectural Press.

- Marcos, Carlos L., Mara Capone and Emanuela Lanzara. 2017. "Digitally Conscious Design. From the Ideation of a Lamp to its Fabrication as a Case Study". In ShoCK. Proceedings of the 35th International Conference on Education and Research in Computer Aided Architectural Design in Europe, vol. II, edited by Antonio Fioravanti, Stefano Cursi, Salma Elahmar, Silvia Gargaro, Gianluigi Loffreda, Gabriele Novembri and Armando Trento, 219-228. Rome: Sapienza University.

- Marcos, Carlos L., and Liz McCormick. 2021. "Digitally Disruptive Critical Regionalism: Climate, Place and Façade". In UIA 2021 Rio27th World Congress of Architects Proceedings, Vol. III, 1661-1667. Rio de Janeiro: UIA.

- Matos, Beatriz, and Alberto Martínez Castillo. 2011. "La cerámica y los maestros modernos 5+1". In Ensayos sobre arquitectura y cerámica, edited by Jesús Aparicio Guisando, 9-23. Madrid: Mairea Libros.

- Moneo, Rafael. 2005. Sobre el concepto de arbitrariedad en la arquitectura: Discurso de ingreso en la Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando. Madrid: Gráficas Arabí.

- Pallasmaa, Juhani. 2005. The Eyes of the Skin. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons.

- Pampuch, Roman. 2014. An Introduction to Ceramics. Cham: Springer.

- Picon, Antoine. 2004. "Architecture and the Virtual: Towards a New Materiality". Journal of Writing and Building, 6: 114-121.

- Picon, Antoine. 2006. "Foreword". In Algorithmic Architecture, edited by Kostas Terzidis, vii-x. Oxford: Architectural Press.

- Picon, Antoine. 2010. Digital Culture in Architecture: An Introduction for the Design Professions. Basel: Birkhäuser.

- Picon, Antoine. 2019. "Digital Fabrication, Between Disruption and Nostalgia". In Instabilities and potentialities: Notes on the nature of knowledge in digital architecture, edited by Chandler Ahrens and Aaron Sprecher, 223-237. New York: Routledge.

- Reza Shirazi, M. 2018. Contemporary Architecture and Urbanism in Iran. Cham: Springer.

- Sakamoto, Dean, and Karla Britton. 2008. "Hawaiian Modern: Vladimir Ossipoff in New territory". Modernism (Winter): 62-75.

- Sanuki Daisuke Architects. 2016. "Apartment in Binh Thanh". Archello 2016. https://archello.com/project/apartment-in-binh-thanh

- Semper, Gottfried, Harry Francis Mallgrave and Michael Robinson. 2004. Style in the Technical and Tectonics Arts; or Practical Aesthetics. Los Angeles: Getty Research Institute.

- Sennet, Richard. 2009. El artesano. Barcelona: Anagrama.

- Torroja, Eduardo. 1998. Razón y ser de los tipos estructurales. Madrid: Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Cientificas.

- Vo Trong Nghia Architects. 2016. "The Lantern". Dezeen 2016. https://www.dezeen.com/2016/11/25/the-lantern-vo-trong-nghia-perforated-brick-gallery-showroom-hanoi-vietnam/

- Vo Trong Nghia Architects. 2021. "Casa en Bat Trang, Hanoi (Vietnam)". Arquitectura Viva, no. 237: 50-55.

- Zumthor, Peter. 2006. Atmósferas. Barcelona: Gustavo Gili.