According to Fernand Braudel,1 urban centres originally appear and develop where the physical trading of goods takes place, even though, at first, this trade is only occasional. Later on, commerce becomes the key element for conservation and self-preservation of the city itself. Henri Pirenne2 makes an even more peremptory statement, declaring that cities are, first and foremost, an economic concept. “Cities are daughters of trade and their essence of being,” he states. More recently, the Harvard Design School Guide to Shopping, edited by Chuiha Chung, Jeffrey Inaba, Rem Koolhaas, and Sze Tsung Leong, presents the rather striking idea that the making of architecture has always been dependent on an exclusion and masking of the centrality of retail.3

Taking what seems to be a shared assumption amongst all these theorists (even though they belong to very different epochs) as a starting point, this paper supports the idea that the binomial city/commerce cannot be separated. There has always been an inseparable, congenital, and even constitutive relationship between urban centres and commerce. Throughout the centuries, although assuming different forms of construction, public commercial spaces have never lost their common bond of being a mix of interaction, city expression, urban architecture, and an extension of the space and public purposes of the urban centres.

However, at some point during the twentieth century, the relationship between the urban centre and commerce changed considerably. With the consolidation of new market models, and along with this new product distribution processes, services, and information, consumption became the paradigm of the modern city4 and commerce and its places took on the main driving role behind the transformation. It is the era of the Shopping Centres that, replacing the streets parks and squares as the new collective space par excellence, recreate admirable worlds and optimized simulations of the traditional public spaces.5

This is when people began to feel, once again, the need to regain a sort of common ground; a shared dimension where spaces designated for trade and social interaction could coexist. To fulfil these ambitions, any project that has as its purpose the aim of defending and improving urban quality cannot avoid considering the issue of commerce, or the underlying forces guiding its development and their ever changing nature. Therefore, the planning of commercial activities cannot assume purely economic and managerial characteristics, but rather it needs to play a central role in the city's discourse.

Urban texture is defined by constructions as well as by the materialization of the opposite of construction, that is, empty space. Empty space is public space, which is not the negative form of the space of construction, but the positive form of the space of the city. These exceptional discontinuities in the overall body of constructions have always played a key role in the urban system, from a functional, formal, and symbolic point of view.

Public space can serve multiple functions, being intrinsically versatile and adaptable to many purposes: Its polysemous nature has always been the reason for its genesis and continuous transformation. It can be a place where people meet to engage in the following activities, politics, justice administration, religion, market, theatre, work, play, music, events, walking, driving, etc.

From a formal point of view, the layout of public spaces defines the way buildings occupy and structure the space. Without public spaces—that is to say without squares, or streets, and therefore without façades, doors or windows—there would be no such thing as a “city.”

Furthermore, public space acts as an agglutinating agent, which is charged with symbolic meaning: it naturally conveys a social quality, being the space where citizens acknowledge their sense of belonging to a community, a community in which people can re-create their common history and identity. The city is made up of urbis (physical urban space, buildings) and civitas (space for citizens and urban culture).

Therefore, from a morphological perspective, public space can be defined as open, free and accessible; whereas, from a functional perspective, the main features of public space are its being communal, shared, varied, multiple, and co-experienced.

This is why, when talking about public space, one cannot simply refer either to architecture or to empty space in itself. On the contrary, talking about public space means, above all, discussing the social and cultural dimension of the latter, which is seen as a place where relationships, urban life and community identity are being created. Public space is what gives birth to urban quality, a sense of “cittadità,” as Lopez called it.6

If the idea of public space is defined by this sense of urbanity, then its discussion cannot be bound to a matter of form, type, or even size or scale. Also, in order to be able to contain public space, a building does not necessarily have to be ancient, or to hold a certain status of “pre-existence.” So, if we assume that the idea of public space is in no way dependent on specific architectural forms or types, size, or history, then it is clear that even a brand new building can easily have an urban quality, or “cittadità,” or be permeated by it. Whether such a building is covered by a rooftop or not makes no difference in this sense.

Perfect examples of spaces charged with a deep sense of urbanity are those places which are dedicated to traditional commercial activities: these are shifting and flexible sceneries which constitute a background to the complex network of relationships and social practises, as well as space and the way this is experienced. Commerce and the city are both located in the deep core of the idea of an urban body, complementing and producing one another, in an inextricable bond. Open spaces and commercial spaces are mutually enriching, they becoming more and more appealing and fascinating, together contributing to the creation of an animated, colourful, perfumed, resonating and surprising urban texture, in which interchange is not limited to goods trading.

According to Max Weber, a classic author in urban studies, the existence of the city necessarily implies the existence of a market place.7 The traditional image of the medieval town is heavily marked by the presence of spaces for trade: streets and squares alike are places for living, socializing, producing and exchanging.

Commerce and the areas in which it takes place also contribute to the shaping of the experience of urban life when middle classes begin to emerge. Open urban spaces become Passages (arcades): covered commercial streets with elegant settings, whose nature continues to evoke their original status. This is that of the street, which in close continuity with the network of the various blocks of buildings, appears as a natural extension of public space.

In the mid-Nineteenth Century, the department store begins to become a widespread model for commercial activities in established city centres. It is a building that is essentially a shop window, the purpose of which is purely and entirely commercial. Being flexible and adaptable to the exhibition of goods, it can gather, under one roof—often with a festive mood and cheerful atmosphere—an impressive number of goods, which can be easily accessed by the public. According to Codeluppi8 department stores have become theatres for new kinds of rituals, which are characterized by anonymity and by the spectacular exhibition of goods to the crowd: “The last sidewalk left to the flâneur,” where the show has the only purpose of selling goods,” says Walter Benjamin. Nevertheless, the big department store continues to have a lively and direct relationship with the urban context, providing a gathering point for the flows of pedestrians and creating synergies with other types of functions.

It is in the Twentieth Century that the city turns into something radically different from the city of the middle and industrial classes. With the explosion of mass-society and the increase in peoples' mobility, as well as with the invention of new technologies and new media, the city begins a process of differentiation: a separation of the various urban organisms from one another and a specialization of functions that become more and more obvious. A new city is born. A sort of urban sprawl where the different urban functions are more and more separated—a separation encouraged by the growing use of private cars—and where, as a consequence, traditional forms of housing and buildings are abandoned in favour of a huge increase in the size and amount of infrastructures. The result of this process is an “erratic and scattered urban context […] atopic and discontinuous,” where “squares and arcades, avenidas, plazas, and also the streets and roads themselves seem to have lost all identity and meaning.” Instead, commercial spaces, now trying to present themselves as ideal surrogates for all forms of traditional public space, acquire new status and meaning, as communal and social spaces. The department store, now “detached from the urban context and taken out of the city, sheds its osmotic architectural form, to become impermeable to the system of open spaces, choosing for itself a dimension that is more related to the definition of its interiors.”9 Today’s big-box stores, retail parks, shopping malls, etc. all confirm this process.

Paradoxically, when faced with more and more aggressive competitors, even traditional forms of local commerce and city organization seem to collapse. The only reactions to this process are, in many cases, projects of urban remodelling that, in the end, are not much more than urban restyling, focused on marketing purposes, often including renovation, communication and promotion strategies aimed at highlighting the “consumable” features of a specific place. This trend often results in a phenomenon of gentrification, which does not differ much from those processes of social and space segregation typically produced by extra-urban commercial systems.10

The ever-existing relationship between city and commerce has undergone many changes, due to much more complex and manifold factors, ranging from the restructuring of financial markets to the deep transformation of production processes. Social and cultural aspects have also to be taken into account, paying special attention to the changing patterns in consumers' behaviour. According to Codeluppi, the birth of a “consumer culture” is to be traced back to the moment when the first shop windows made their appearance on the streets, at least a couple of centuries ago. The act of going shopping is no longer just a way of providing what is needed, but it is also a moment for leisure and recreation. This has laid the foundations for a new kind of urban life, where the intimate relationship between public space and commerce has been broken up. Amendola himself talks about the process of “windowfication” of the city. This is a process where the sense of sight is enhanced above all other senses, inevitably influencing the spirit and representation of public space.

Looking at the complexity of todays' commercial scene, in which the dual model in forms of commercial distribution (big concentration/local retail) stands out more and more as if it is the only possible model. We feel it necessary to try to understand how the planning of commercial spaces is changing, as well as how these changes affect the shaping of the city. It is possible that an interesting discussion may now arise, both from a planning-related perspective and a socio-cultural one. Bearing in mind the need to restore a social purpose to the places of commerce, thus also restoring their ability to produce “quality city life,” it is our intention to outline the mechanisms that either underly the mutual making of city and commerce, or their mutual annihilation.

For the empirical research carried out during the PhD research, we took the city of Lisbon as a case study. The relationship between commerce and the city has been analysed through the definition of three macro-categories, illustrating three different types of commercial systems and their specific impact on the making of the city, as well as on the life of the city itself. The taxonomy of these three macro-categories is based on the interpretation of the Portuguese capital's existing commercial patterns from 1970 to 2010. In particular, the study focuses on Lisbon’s commercial systems over the last 45 years, analysing how these structures interact with the urban context, the open spaces, the system of infrastructures and society at large.

The objective of the Lisbon case study is to examine and explain the role of commerce and its place in the transformation and consolidation of the current city/territory, and its urbanity. Very aware of the importance of the action-oriented knowledge dynamic, the empirical work pretends to provide an analytical and project-based contribution to the theory. It is a methodological instrument and a technical and scientific support for public institutions, local authorities and private entities, and is focused on delivering a framework of knowledge and models that can reposition commercial spaces in the making of the city.

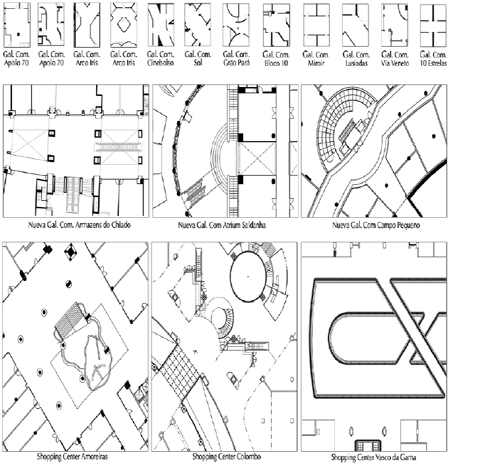

The result of the study is an inventory of the commercial systems in the city of Lisbon. Those places are systematized and catalogued in the Atlas of Lisbon Commercial Systems, which demonstrates the validity of the three macro-categories and provides the evidence to support the research findings. Moreover, the Atlas sets criteria, typologies and elements of relevance for public policies spatial planning.

Summarizing the relevant content, the Atlas includes the identification of the commercial spaces on maps, which show their location in relation to the urban system, their dimension and typology. For each commercial place analysed, the study provides data on the date of opening, author, surface area, number of shops, anchors shops, parking area, etc. It also undertakes a diagnosis, which places an emphasis on charting physical and urbanization characteristics: uses of the building, morphology of the commercial space (represented in the design plan, elevation, organization of the sales structure, interior circulation with the identification of the spaces of socialization, relation between the interior and the exterior, etc.), relation to the road system and public transport accesses, open space systems, main city flows and focus points. A second set of variables arises from the previous analysis. These are mainly the effects on commercial systems that are characterized by other spatial configurations and the contribution to the construction of qualifying images and qualifying spaces.

Figure 1.

Atlas Sheet_Identification on map of the commercial system of Lisbon. Source: Drawn by the author

Figure 2.

Atlas Sheets_Representation of the Citi Arcade in the Avenidas Novas area. This is a sample of some of the architectural and urban characteristics analysed in the case studies (identification on map; insertion in the urban fabric; interior circulation; interior/exterior relation; parcel structure and building type; road system, public transport and data such as date of opening, author, surface area, number of shops, anchors shops, parking area, etc.). Source: Drawn by the author

The established database of the commercial places in Lisbon is a starting point for creation/transformation actions. As an example, some urbanization actions are proposed: refitting, change and/or mixture of uses, densification, improvement of permeability, improvement of public transport, improvement of the exterior public space quality.11

This analysis of Lisbon’s recent commercial history has led to the definition of three macro-categories of commercial systems that illustrate three types of relationships between the city and its commercial dimension: symbiotic, commensal, and parasitic.

Lisbon’s architectural solutions to commerce belong to the first of our three macro-categories. They are what we call a “symbiotic” system, which is an enhancement of a type of commercial space that is integrated into the established urban context, if not defined by it. These “symbiotic” spaces participate in the city's physical and functional interchange, making it possible in the first place. Such a type of commercial space, not only promotes economic activities, but also produces urban quality, becoming a point of reference for the area. Citizens/consumers are free to circulate inside and around these commercial spaces, as well as in the open spaces (according, of course, to the opening hours). The network of symbiotic commercial spaces does not limit itself to taking advantage of the city, but provides the necessary conditions for a mutual improvement of the space in the city and the space for commerce. A good example of symbiotic commercial space is the arcade model (small in Lisbon’s case). They are open on the ground floor of residential buildings, located inside the city's dense, traditional layout. This type of commercial space has a relationship of direct interchange with the urban context, creating a symbiosis with the flow of pedestrians and a synergy with other urban functions.

A similar process occurs with some of the shopping centres that stand on their own but are located either in central historic areas of the city or on the residential areas of the city. This can even be the case with department stores or with some middle-sized supermarkets. These are what we call “commensal” commercial systems. These are relatively big containers, independent from the surrounding urban texture, compared to which they appear to have a completely different “nature.” Nevertheless, these commensal commercial spaces fit in the urban structure, often becoming a constituent element of the urban organism itself. They are flexible and adaptable structures, designed to present goods; their ground floor is conceived as an articulated system of shop windows that also serve as entrances, helping to dissolve the barrier between inside and outside. They grant the customers the possibility of a fluid interchange between these two dimensions, both on a visual and a physical level. They act as a catalyst for society and as a revitalizing factor for open spaces, both on a local and regional scale. They are located near the main or secondary networks of infrastructures for goods distribution, and are often built in areas within easy reach of public transport.

Lastly, with the on-going separation and diversification of functions, encouraged by the use of private transport and by the network of roads, another standard of commercial buildings begins to emerge. Such buildings depend heavily on their strategically positioning near the main network of arterial infrastructures. They are introverted and completely self-contained structures. Moving towards the outskirts of the city, or even into extra-urban territory, they lose the ability to create a symbiosis with the open systems around them. These are what we call “parasitic” commercial systems. Shopping centres, retailtainment centres (retail + entertainment), retail parks, factory outlet centres or even hypermarkets: they are all a result of this process. What is most ironic about this, almost a paradox, is that if on one hand these structures physically separate themselves from the city, on the other hand they tend to reproduce the city itself on their inside. Imitating urban morphology and the type of experience that could be had in a traditional city, they promise everything that was once offered by the city, although eliminating all that is unpredictable, such as the weather, the dangers of traffic, and the disturbing “spontaneity” of public spaces.

Figure 3.

Circulation spaces (section and plans) in the three commercial three macro-categories. Source: Drawn by the author

Actually, the amazing Colombo Shopping Centre,12 or the remarkable Freeport Outlet Alcochete,13 are much more than giant markets or enormous commercial areas; they fit in the urban structure as adaptations or reproductions—although in a concentrated and introverted form—of the traditional places that were once naturally devoted to commerce and urban cohabitation. These places offer a concentration of objects and images that evoke, through relaxing and nostalgic atmospheres, a dream city, a city where all is peaceful. Metaphor is everywhere, and hedonism a rule. These commercial spaces embody a fascination, a sort of longing for the city: what they offer is a reflected image, an optical illusion. But how do they include the public in its realm?

From simple corridors, inside continuation of the outer pedestrian flows, the circulation spaces in the shopping spaces are becoming larger and more complex. Floors rise and games voids are increasingly seeking to be on show. They are not just flow spaces that simply make the shopping centre's distribution function, but they are places to stop, sit down and talk, and a series of equipment normally found in traditional urban spaces—banks, fountains, gardens, signals, etc. can be found. Have the circulation spaces of the parasitic commercial systems been transformed into new public spaces?

It should be remembered, though, that these commercial systems are incapable of reproducing a large number of features of the traditional city, such as cultural and ideological diversity, the versatility of functions and purposes of the common space (with all the personal relationships that it creates), and all those spaces for urban activities that do not involve or require consumption of any form. That is to say, they do not express the functional and relational complexity of the city; they do not express urban quality. The essence of urban space, its public dimension, is rooted in the idea that it should contain freedom, it should offer citizens a chance to meet, interact and move without being tied to a given set of rules and private control mechanisms. Shopping malls, retailtainment centres and all kinds of similar private commercial structures are indeed founded on these rules and control mechanisms, which constitute their essence of being. This is why they cannot encourage the development of independent and plural social relations, or an intense public life. What they encourage is exactly the opposite.

The contrast—the conflict even—between traditional systems of commerce and today's large structures should be able to trigger processes of competition, which in turn should lead to a complete re-definition of the layout and management of the commercial network of sale and production practises, and, therefore, of the city itself. This is exactly the point: To re-design the city, to re-think it not only in terms of a place where we can find positive and inspiring images, but also as a place which is constantly enriched by the variety of its functions, as well as by its spatial complexity. We think of a city where exchanges and relationships among individuals are free and possible. Not only would civitas inhabit and live in the city: it would be its very soul.

The above analysis shows the need for a number of measures that should be aimed at re-establishing a sense of balance in the city's functional structures. This could take place through the improvement or elimination of unbalanced models, as well as through the introduction of complexity in the areas where it has ceased to exist. Furthermore, a fair distribution of functions in the territory would diminish the differences that potentially underlie the entropy of contemporary urban systems. This does not mean creating self-sufficient urban units, but rather a polycentric system, where one pole with specific functions (even commercial ones) actively participates in the making of the whole metropolitan organism. In brief, this analysis highlights the need to develop structures not only for commerce, but also, and mainly, with commerce. Wherever shopping is willing to relinquish complete control of its spaces and welcome activities separate from commerce, the public will be revived and reoccupy its place in the realm of the world's most social of activities.

A symbiotic relationship between commercial structures and the city can be re-established. The challenge consists of finding the urban and architectural forms14 that most satisfy the above mentioned needs. These forms would have to be capable of creating “cittadità,” for which purpose it would be necessary, first of all, to think about how to reassemble a whole that is now divided into separate parts. Commerce needs to rediscover how to act as an agglutinating urban element. It is exactly in the need for a city that commerce and social life can find new common ground.15

Do we, therefore, agree with those who assume that the degree of success of a symbiotic commercial system is irrefutable proof of urban quality? Does the crisis of the traditional forms of commerce coincide with a crisis of the city? And then, can the planning of commercial spaces go back to being one with the “making” of the city itself? On the basis of the present study, we believe we can say that the answers to these questions are all positive.