Introduction

In the late 2016, the PritzkerSwiss architectural office Herzog & de Meuron presented their competition-winning plans for a modern art museum in Berlin: The Museum of the 20th century. This was to be an extension of the New National Gallery (Neue Nationalgalerie), designed by Ludwig Mies van der Rohe between 1962 and 1968 (Fig. 1). Initiated by the competition, the concept of transparency in modern architecture has reemerged as a topic of discussion in architectural circles. The architects Jacques Herzog and Pierre de Meuron have recently published a book on the analysis of transparency in the works of architects and artists such as Mies van der Rohe, Bruno Taut, Gerhard Richter, and Marcel Duchamp.1 Although the book’s theme is derived from Mies’ Farnsworth House (1945-51) in Illinois, Herzog and de Meuron analyze various aspects of transparency, ranging from the effect of camouflage in terms of blending into the surrounding, to the literal and figurative meaning of ‘seeing through.’ As noted in the book, transparency has essentially been the symbol of pure modern architecture and was appreciated with great enthusiasm in the twentieth-century.2 Mies, for example, has been primarily associated with glass architecture based on the metaphor of “skin and bones,” which makes reference to his Glass Skyscraper design in 1922. Having experimented with various styles of glass in his buildings, he has intended to express different qualities of transparency, translucency, opacity, and reflectivity.3

Figure 1.

New National Gallery by Ludwig Mies van der Rohe in Berlin, 1962-68. Photo: Jean-Pierre Dalbéra, 2013.

Since the twentieth-century, transparency has been associated with the dissolution of the façade and the dematerialization of the wall with its metaphors of invisibility, weightlessness, clearing, absence, and abstraction.4 Using the New National Gallery as the central focus, this paper argues that, in reality, transparent buildings do not always allow clear vision, free flow, circulation, connection, and accessibility. It evaluates the dilemma of the intentions and outcomes through the debate on transparency that has recently resurfaced by critically reading essential architectural history texts. As a result, it shows that the transparent surfaces of the New National Gallery, in particular, produce a temporal and reflective screen that frame the city and propose a new opaque layer through changes in the weather.

The Gallery as a Free Space

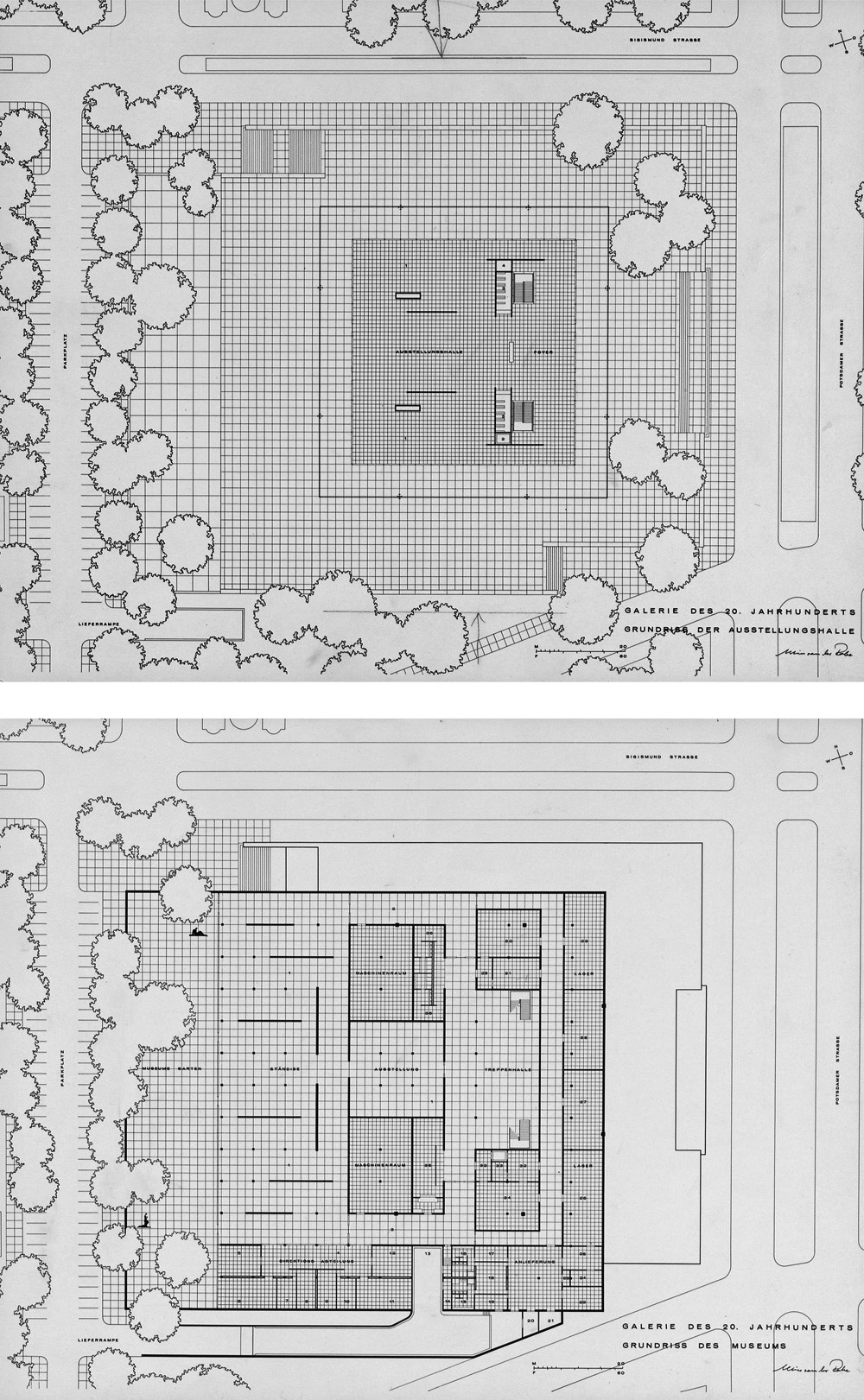

The New National Gallery´s plan consists principally of two architectural elements: a large platform and a roof in the shape of a square (Fig. 2). The thick steel roof, which covers the whole building, has no false ceiling and, thus, it allows the audience to perceive the grilles inside the roof. The large platform, which is the base floor of the entrance level and the main gallery space, can be accessed by a few steps leading in from the street. The building has retaining walls on all sides of the parcel, since, for Mies, the gallery should manifest itself as “a monument in the city.”5 The base platform and the main gallery space, which is reserved for temporary exhibitions, emphasize the concept of the void through modern use of the free plan (Fig. 3). Conversely, the gallery space below, which displays the permanent exhibition, is partitioned by columns, walls, storage rooms, and can be accessed by two staircases from ground level. In contrast to the glass walls of the main gallery, the lower gallery is enclosed with white paint and materials (Fig. 4).

Figure 2.

Ground (top) and basement (bottom) level plans of the gallery. Photo: bpk / Kunstbibliothek, SMB / Dietmar Katz, 1963.

The building is based on the structural ideas of Mies’ two unrealized projects: The Bacardi Rum Corporate Headquarters in Santiago, Cuba (1957) and the Georg-Schäfer Museum in Schweinfurt, West Germany (1960-61). In these buildings, Mies intended to create large spaces without interior internal columns, but he instead managed exterior expressive structural supports that related to his ‘skin and bones’ architecture.6 Along with some other modern architects, such as his first master Peter Behrens, Mies searched for ways to emphasize and express the steel structural system (Fig. 5). On the outside of the gallery, he applied Behrens’ ball-and-socket joint system in the Turbine Hall of AEG (1909) in Berlin in order to connect the steel columns to the roof projection.7 With the aim of materialising the idea of pure transparency, he used glass on all façades and displayed the entire steel structure system. In the design process, he analysed the shadow cast by the sun. Shadow on the glass surfaces would prevent reflections on the glass and render the borders of the gallery invisible; the intended effect of invisibility would highlight the idea of ‘absence.’ Contextually, the position of the gallery was derived from the movements of the sun rather than from any other environmental input.8

The gallery as a transparent glass cube initiated controversial arguments among museum visitors and professionals since it challenges the common modern understanding of the opaque white cube. It contradicted the idea of the modern museum as a sanctuary in which one could reflect in neutral interiors without any outer disturbance. The critical audience disagreed with the idea of being able to see paintings from the outside. Ignoring the free space of the gallery as a flexible theatre stage, curators, and artists further expressed their confusion about not having solid walls on which their paintings could be hung.9 Bewilderment was further emphasized by an incident that took place during the opening ceremony. The gallery director expressed utter bewilderment about where to hang the pictures, and Miles´ reply was, ‘That’s your problem, Dr. Hofmann.10 However, the architectural historian Detlef Mertins points out that Mies’ objective was to search for new ways of displaying art and to encourage new ways of making art by conceiving it as “… a framework or infrastructure for an experimental approach to art and life in which the question of autonomy extends to the curators and artists themselves.”11 One example of this could be that, since the 1970s, space has been used for multimedia works, installation art, and performance art.12 Differentiating from the meditative and introverted character of the white cube, the New National Gallery thoroughly displays itself, the steel structure, artworks, audience, pedestrians, and the cityscape.

Juxtaposed Images on the Reflective Screen

The intended effect of transparency is reflected in the seminal essay, “Transparency: Literal and Phenomenal,” written by the architectural critic Colin Rowe and the painter Robert Slutzky approximately at the same time as the New National Gallery was being constructed. In the essay, Rowe and Slutzky suggest a duality: literal transparency implies a material condition, such as glass, whereas phenomenal or seeming transparency refers to a spatial organization and simultaneous perception of different locations.13 The authors examine the characteristics of Cubist paintings—such as frontality, suppression of depth, and contraction of space—and demonstrate their application to architecture in terms of phenomenal transparency. They argue that phenomenal transparency was much harder to achieve than literal transparency since the former constitutes three-dimensional layers of superimposed spaces, which do not obstruct one another.14 However, Mertins points to the inadequacy of Rowe and Slutzky’s ideas, who were unsuccessful in revealing all aspects of transparency, and criticizes them for reducing transparency to mere visuality and a two-dimensional artistic conception.15 The architectural critic Anthony Vidler asserts that literal transparency can easily turn into obscurity and reflectivity since the reflected scape and interior view become superimposed on glass surfaces.16 Nevertheless, one can very clearly see the interior at night when the building is artificially lit from inside and glows brightly (Fig. 6). In many of his buildings, Mies used a specific type of glass that had a reflective quality, rather than seeing the superimposition of reflections as an obstacle to achieve literal transparency. The architectural theorist Jose Quetglas interprets this as the dissolution of interiority and exteriority that leads to the creation of a new experience. He points to the dual character of image in the Barcelona Pavilion as the audience feels like being in the interior space while they are viewing from the outside, “Could it be that the pavilion has no interior, or that its interior is an exterior? Or is it that the visitor has seen himself rejected by the pavilion, bounced back to the exterior at the moment that he was closest to entry?”17

The relationship between inside and outside is evident before even entering any architectural work by Mies. In the New National Gallery, he presents the glass façades as a screen or a frame between the exterior and the interior areas. By so doing, he expresses the temporality of cityscapes by defining glass walls as changing backgrounds for the displayed artworks and furniture inside.18 Glass becomes a flat surface that turns the environment into part of the décor in interior space – an image to be displayed and gazed at (Figure 7). Framing allows for the public to see what the architect wants them to see, for example the glass surfaces of the Crown Hall (1950-56), which frame the city of Chicago as something to be viewed. Berlin, conversely, becomes a mural for the artworks in the New National Gallery.19 Observed from the interior space, according to Quetglas, Berlin cityscape emerges as a two-dimensional mural, frame, and sticker on the transparent façade.20 From the outside, the glass becomes a mirror, which reflects the cityscape, landscape, and sky (Fig. 8). The changing views of the city become images on the screens, which are framed by the steel structural system (Fig. 9). The cityscape changes continuously throughout the day and over the seasons, so that the transparent glass turns into a temporal, ephemeral, and reflective screen.

Condensation as a New Layer

Mies used glass to allow the transmission of simultaneous and superimposed gazes as suggested by phenomenal transparency. When approaching the gallery from the ground level platform, it is possible to simultaneously see glass walls, an entrance level gallery, cityscape behind the building, and reflection of the view on the glass. Similarly, when descending to the basement level to enter the sculpture garden, it is possible to simultaneously perceive sculptures, greenery, the lower gallery, and to have a partial view of the city. The “almost nonexistent” glass surfaces can be seen as a thin membrane that erases the boundaries between public and private and renders the line between interior and exterior ambiguous.

The architectural historian Fritz Neumeyer argues that the transparency of Mies’ buildings proposed freedom of movement in space and connection with environment.21 In its entirety, the clearly defined and strongly connected spaces of the gallery absorb the movements of the audience without directing them to a location or route. To achieve flow and fluency through landscape, Mies avoided any unnecessary window divisions, which would obstruct the view. According to the contemporary sociologist Richard Sennett, this attempt derives from Mies’ aesthetic concerns.22 As Mies puts it, “The exterior and interior of my buildings are one. You cannot divorce them. The outside takes care of the inside.”23 However, despite the reciprocal relationship of visuality in interiority and exteriority, the qualities of air, sound, and smell do not flow freely through spaces at all times. As Sennett notes, it was a modern approach to establish interior and exterior visual connections, but to seal off other senses from outside.24 Visuality was the dominant paradigm of modern aesthetics, whereas tactile, acoustic, and climatic conditions were of secondary importance to architecture. In the New National Gallery, the precise disconnection between senses remains. The role of transparency as a means of connection and flow between audience and environment is suspended. One can perceive the sculpture garden from the platform but cannot have access to it, or can view the cityscape from the ground level gallery but cannot hear any sound or feel the weather outside (Fig. 10).

An on-going discussion about the glass walls elaborates the argument. Cold weather and icy wind interfere visual and conceptual transparency in the gallery. In winter, due to humidity, condensation occurs on glass surfaces and blurs the clear vision of the gallery (Fig. 11). In order to solve this problem, many precautions have been taken since then, but none have been successful yet. For example, temperature and air circulation of the gallery were increased. An infrared beam was used to reduce humidity, and curtains were hung on the walls in order to protect the artworks from the ultraviolet light. However, curtains produced static electricity because of the reduced humidity and disrupted the view.25

The formation of condensation obstructs vision on both inside and outside. Most importantly, it makes the air visible. Although the weather is not felt in the climatically controlled interior space, it is clearly perceived. Condensation acts like a veil, through which no gaze but only partial light can pass. At some points, one can peek from behind the blurry glass, as if sneaking a look through translucent curtains. From the exterior, rather than reflecting Mies’ objective of pure transparency, the building has the impression of a rectangular haze or mist. Instead of showing the artworks inside, the glass gallery displays the effects of cold weather. Pointing to this critical problem on the way of obtaining pure transparent façades, condensation on the windowpanes emerges as a new opaque texture. It produces an ephemeral and almost tactile sense of opacity, as if the glass walls are entirely smudged, only to disappear when the weather is mild enough.

Conclusion

This paper reflects the dilemma between intentions and outcomes in an architectural work of the mid-twentieth-century that has been retold through a recent book on transparency. As Herzog and de Meuron argue, glass buildings became so ubiquitous in our age that people do not notice or dwell on them anymore.26 However, issues on the effect of transparency, translucency, and opaqueness of the glass concern various contemporary buildings, ranging from Herzog & de Meuron’s Laban Dance Centre (2003) in London and Allmann Sattler Wappner Architekten’s Dornier Museum (2009) in Friedrichshafen, Germany to SANAA’s 21st Century Museum of Contemporary Art (2004) in Kanazawa, Japan. In order to thoroughly reveal the potential of glass, these buildings should be handled and grasped in accordance with their essence. As this paper shows through the case of the New National Gallery, it was one of Mies’ primary objectives to make artists and curators understand, interpret, and engage with the size, material, and transparency of the glass cube.

The effect of transparency did not succeed in the New National Gallery at all times. Mies’ intentions were not very complicated at first when he designed the building; yet, its materialisation caused an elaborate analysis and transformation due to its context and content. Problems encountered on the way contradict the remarks of Rowe and Slutzky, who emphasize that the achievement of literal transparency in architecture was much easier than phenomenal transparency. Environmental conditions, such as weather, daylight, artificial light, and inability to construct a direct connection of vision, touch, smell, and sound between inside and outside, alter the outcome on the glass surfaces. However, taking into consideration the gallery’s potentials as a glass cube as Mies analysed, it can be read as an ephemeral and temporal artwork per se, whose appearance changes throughout the day and over the seasons. The transparent façades become a frame, screen, mirror, veil, and fog, which reflect and superimpose clear images and hazy appearances, to be uncovered and experienced by passers-by and visitors. The gallery thus challenges the modern notions of transparency, vision, flow, circulation, and accessibility, as it presents the glass as a reflective screen and a condensed opaque layer.