Doing Research with Video

This paper is a presentation of the project RESEARCH VIDEO, which strives to combine the medium of video and scientific research on theoretical, practical, and technological levels.

As experienced during the Zurich conference “The Art of Scientific Storytelling” in January 2019, a large group of scientists, scholars, and students from all educational institutions across Switzerland showed interest in the use of video to convey their findings and create scientific knowledge. At the same conference, an important number of artists, creatives, and designers were present and showed interest in working with science and scientists as part of their creative endeavors. Dr. Rafael E. Luna, a researcher of biochemical mechanisms of cancer at Harvard Medical School, explained in his presentation that scientists from all fields can use literary storytelling to convey their research findings. Scientific storytelling helps us to ask the right questions, and to answer them in a way science becomes more understandable. If we use evocative descriptions and structure the research process into a story, we might reach a wider audience and show more than the tip of the iceberg. Sophisticated “fancy” and obscure theoretical language intimidates the readers, especially those outside the discipline. It also prevents the scientific knowledge from being fully understood. If only Pierre Bourdieu had written his important yet highly intricate writings in more evocative language, many student’s headaches could have been saved; however, this should not sacrifice scientific righteousness.

Storytelling and evocative writing can be translated to video. In the past decades we have seen the emergence of web-documentaries and other non-linear storytelling forms that widen the possibilities of conveying knowledge through audiovisual expression. The RESEARCH VIDEO project finds itself exactly on this crossroads and looks into the possibilities of video publication in the social sciences and beyond.

RESEARCH VIDEO is also the development of an online tool that enables videos to be annotated, such as annotation would be done on a scientific text (Lösel 2018). Motivation for this project came from the need to have tools to present research findings in the performative arts, artistic research, and other forms of practice-based research in an academic and scientific context. The goal is to set up a new standard for scientific publication through video that suits the needs of artistic and academic communities while bringing scientific content beyond the borders of experts.

The project consists of a multidisciplinary team: software developers, filmmakers, artists, scientists, and two PhD candidates who “write” their doctoral thesis through the use of annotated videos. One candidate focuses on the field of contemporary dance while the other focus on audio-visual ethnography in the field of social anthropology.1

Marisa Godoy is a dance artist with over thirty years of professional experience. In her case study, she investigates collaborative creation processes in cooperation with various dance artists whose practices explore out-of-the-ordinary ‘modes of being’ that aim to foster an enhanced perception of self, other and environment. Her doctoral research is embedded, informed, and shaped by practice. Through the use of video and video-annotation with the RESEARCH VIDEO tool, she challenges traditional ways of reporting and analyzing data: a process that seeks to obtain new insights into knowledge transmission within the performing arts and artistic research fields.

The other RESEARCH VIDEO case study is led by Léa Klaue, the author of the present article, which presents an audiovisual ethnography on the topic of independent child labor in Bolivia in the field of social anthropology.

As the renowned anthropologist and storyteller Paul Stoller (2008, 118) calls it, the practice of ethnography is “weaving the world”. Our threads of yarn are the accounts, experiences, and the stories gathered from the people we encounter in the field. When these are woven together, a pattern appears. The pattern is the anthropological account of the world. In the following chapters I delineate how the RESEARCH VIDEO tool helps me to join the threads of audiovisual and textual material gathered during anthropological fieldwork in order to create a scientific and compelling pattern.

Audiovisual Ethnography on Child Labor in Bolivia

Child labor is, in my opinion, a topic that is a perfect case to be tackled using audio-visual tools. This is not only because the topic is already widely documented—it is also misunderstood and misinterpreted in the mainstream media through communication from (functioning as advertisement for) NGOs—but also because the visibility-invisibility interplay is inherent and can be deconstructed via montage.

In fact, young people who start lucrative activity before it is legally accepted according to international standards are, in a metaphorical sense, the biggest and most invisible social group in Bolivian society.2 Invisible because nobody really wants to see them: neither the state which qualifies their lucrative activities as illegal and as one of the causes of perpetual poverty, nor the civilian population who use their services but discriminate against them.

When I went to Bolivia for the first time in 2015 with the aim of audio-visually documenting child labor, I wanted to create an image that differs from what can be seen in the West. In Western “developed countries” children’s work is often represented as forced labor and exploitation, while the children are seen as passive victims. I wanted to give voice to the children who were independent and free workers but still forced by their condition and family situation to earn money themselves in order to survive.

I saw working children in every Bolivian city, at every street corner, selling chewing gum, cleaning windshields, and performing acrobatics at traffic lights. I found them in markets, pushing wheel-barrows with groceries, and helping salesladies. When I entered cemeteries, I didn’t see any adults working, there were only children: the youngest of whom were cleaning tombs and carrying holy water while the more experienced ones were playing instruments, singing, and praying for the dead. Through my investigations, I also learned about the invisible group of children and adolescents employed in private homes and in illegal sugar cane fields and copper mines.

It is relatively easy to create this terrible picture about “poor working children” in Western minds, which is the trademark of most international NGOs. It enforces the perception of child labor as being problematic and destructive rather than presenting more reflected insights into this nuanced topic. As I dug into the field and grew solid relationships with active working children who were willing to let me enter their lives and portray them with the camera, I realized how complex and multidimensional the issue of children’s work is.

I collected points of view, insights and aspects, reflections upon the reasons, the consequences, and the side effects of children’s work in a multitude of contexts.

What first interested me was the organizational incentive and power in functioning syndicates led by working children. They defend children’s right to work and demand recognition and protection by the State. The very fact that syndicates led by children exist, which can be considered as “pro-child labor”, already turns upside down the preconceived ideas of the “poor child workers”.

To tackle this topic ethnographically, I had to give the young workers a means of expression. For the video-ethnography, I used participative and creative methods such as “Ethnofiction”, an experimental ethnographic genre created by Jean Rouch in the 1950s mixing performative acting and anthropological filmmaking. I conducted interviews, produced planned and spontaneous short fiction films with the children and teenagers as actors, directors, and storytellers and spent days simply being with them at home or work. The presence of the camera created a playful setting where young people had the opportunity to be creative and where storytelling would unfold and give me the threads with which I could weave an ethnography.

Enrich, Enhance, Annotate using the RESEARCH VIDEO tool

The first finding I deduced after ordering my research data, and after producing my first documentary film about the topic,3 was that it was impossible to align the material into a linear documentary film without losing the scientific nuance.

The data is intertwined. To give the ethnographic construct its fundament, I had to divide it into chapters that are connected but that can be read in any order. The video chapters are divided into different topics, people, and places, and they are connected to each other via references and annotations: the same as in a text.

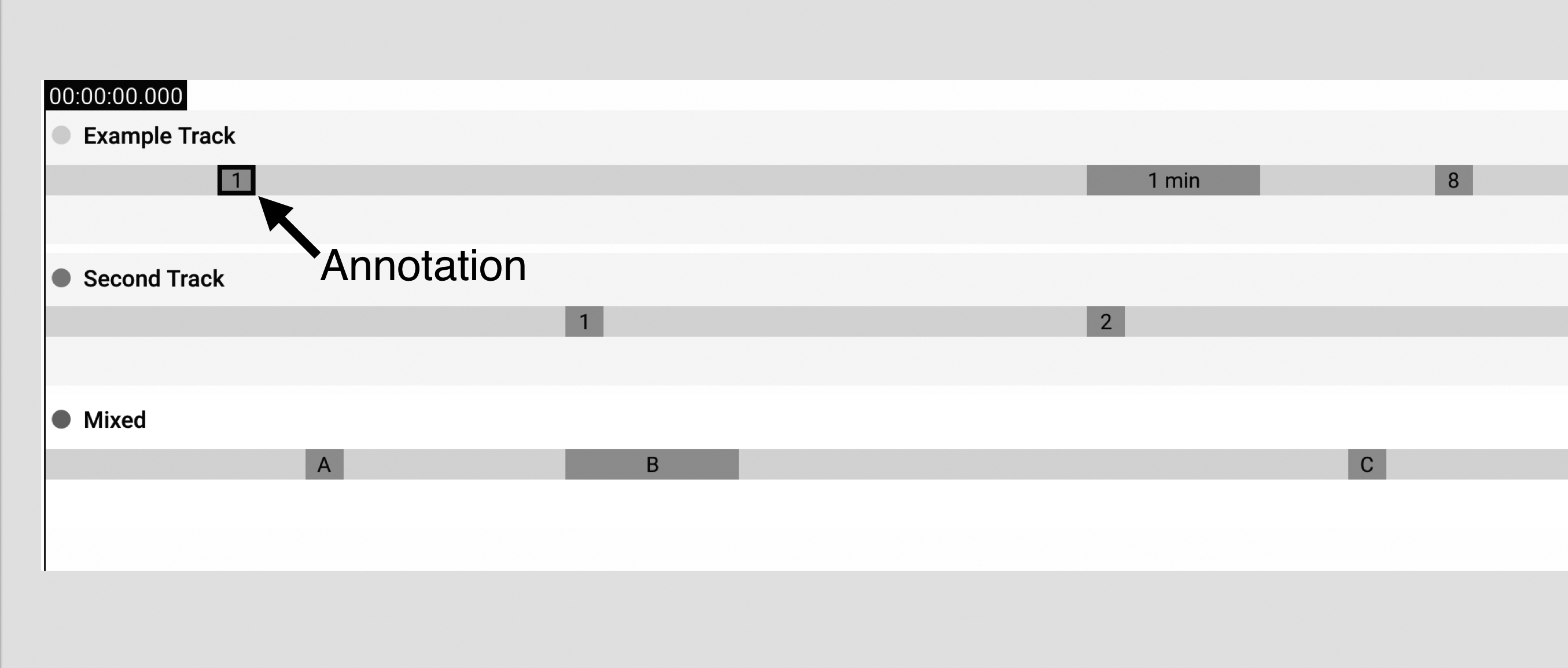

The edited video material is then enriched and enhanced in the RESEARCH VIDEO tool,4 where annotations are added to specific moments in the videos. Annotations appear on various tracks in the timeline of the video, and the tracks can be added and renamed according to the structure of the annotations (Figures 1, 2, and 3). The annotations can be texts that explain what is happening in any given situation as well as provide background information or simple keywords or tags. References and hyperlinks to other videos and other documents can also be added in the annotations.

The annotations appear on the right side of the video in the “inspector”. When the box “Current annotations only” is checked, the annotations only appear when the video reaches the moment at which they were placed on the timeline (Figures 4 and 5). The video can be paused and replayed at any time, which enables a smooth viewing, reading, re-viewing, and re-reading of video and text as one.

Figure 4.

The layout of the Research Video prototype with ethnographic film material from Bolivia. http://rv.process.studio.

Figure 5.

The layout of the Research Video prototype with ethnographic film material from Bolivia. http://rv.process.studio.

The RESEARCH VIDEO tool enables the video to paint a more in depth picture by pointing out the author’s intention thanks to the integration of text within the video. Video is a two-dimensional construct that represents our three-dimensional reality. To picture this three-dimensionality within the two-dimensional frame, we add montage, frame, contrast, focus, depths, and other effects (MacDougall 2006, 270). Using the RESEARCH VIDEO tool, I argue that the three-dimensionality can be enriched with reflexive and background information around the video material. Also, providing more elements to the whole construct activates the imagination of the reader/viewer. In Colette Piault’s (2006, 371) words, video uses a “cinematic strategy”, which emerges from the dialectic movement between knowledge and imagination.

Research Film in the Social Sciences

The tool ‘video’ has been used in scientific research since its invention. In fact, one of the first ever documentary films, Nanook of the North by Robert Flaherty in 1922, is also recognized as one of the first anthropological films. Robert Flaherty was an explorer, and through his attempt to produce a realistic (but staged) portrait of the inhabitants of the Arctic, he created a new genre. This was a genre that would later be used to represent life and society with a certain attempt for objectivity and analysis to converge.

Anthropology and Social Sciences have used film and photographic representations to illustrate findings since these technologies have been available. However, these audiovisual means have merely been used as illustrations accompanying text rather than as a research and publication medium themselves. The debate “text vs. film” has had a long history in anthropology and has been the leitmotif of the development of the field of visual anthropology in academia. Opinions have diverged, been reconciled, and have then diverged again. Nowadays, the field of visual anthropology and the ethnographic film genre are rooted in the academic discourse, and anthropological research with audiovisual means is conducted all around the globe. Despite this, few anthropology departments (or disciplines related to the humanities) allow their students to graduate exclusively with an audiovisual project instead of a written thesis. Graduation thesis projects that are created using audiovisual media often have to be accompanied by a written thesis in order to be accepted. There are still today only a few possible ways of publishing anthropological and ethnographic films in peer-reviewed journals in order to gain academic recognition. Audiovisual files are still seen as an illustrative accompaniment to traditional journal papers. Films produced in social science and research settings can be seen in anthropological, ethnographic, documentary, and other non-fiction film festivals. This helps to promote the genre and make its knowledge accessible to a wider public; however, festival screenings are still not seen as equivalent to journal publications.

If we look more closely at the medium of video, despite its acceptance in the academic spectrum, it carries a multitude of advantages and disadvantages when used as the canvas of scientific research.

The Anthropologist with the Camera

As an anthropologist working with people, the use of the video camera in research is both a gift and a curse. The curse involves the bulky gear and the technical skills as well as the attention video cameras can attract in certain settings. Sometimes the camera can impose preconceived ideas in people’s minds. Also, the discussions about the filming strategies and agreements require patience, adaptability, and pedagogy.

Despite these challenges, the camera is mostly an asset because it can capture an unparalleled amount of data and depth in a very short time. Video captures a richness of detail, such as subtle bodily gestures, facial expressions, tone of voice, or embodied performances, all of which transcend textual descriptions in written anthropology (Suhr and Willerslev 2012, 4). Those elements which Sarah Pink (2005, 277) calls “embodied metaphors” are sometimes impossible to count and identify and impossible to describe at the video level.

Possible or not, one might be compelled to ask if we could not simply describe and quantify all these aspects with words. Is it possible to create the detail necessary to transform the meaning of these subtle nuances through text? Can one bring the subject to life on paper the way it can be done through film?

Many scholars who have been disappointed by the use of visual tools argue that visual technologies are more a mimetic disposition, a “simulacrum of reality” (Hastrup 1992), which only captures features of social life that are visible (Suhr and Willerslev 2012). And it is the invisible, the meanings, and deep truth behind the visible that social scientific inquiry tries to uncover. Is it only reachable through textual construction?

What is finally sought is the meaning through which analysis and theory can emerge. And the only way to create meaning is by using a certain narrative structure (Henley 2006, 377). There are many ways of creating a narrative: the choice of starting to film something in a certain moment with a certain frame and the following chronological alignment of the captured sequences is already a narrative choice. Depending the genre and style the film-makers want to produce, they will try to convey a more concrete meaning to the material through a careful montage when editing.5 The decision-making of which parts of the “captured reality” are kept or discarded and in which order they will appear in the video is what Paul Henley calls the “Guilty Secret of Ethnographic Film-Making”—a power that lies in the hands of the editor and the possibility of transforming reality through montage. This is a paradox which is often believed to be the ethnographic enterprise: an attempt to portray reality as untouched as possible. Making an ethnographic film is not the same as holding a mirror up to the world, but rather entails the production of a representation of it; in the words of the documentary film-maker Dai Vaughan: “film is about something, whereas reality is not” (1985, 710).

While the ethnographic video’s meaning is shaped by whoever made it, the viewers’ reception underlines the final meaning. There are, in fact, a potentially infinite number of meanings that can be assigned to a work as there are infinite numbers of spectators or readers who could potentially receive the work differently (Henley 2006, 378). The act of viewing a video and processing it always involves a certain self-reflexivity. Cognition and thoughts are processed into an abstraction of the meaning understood. This is where theory lies within the film-making enterprise.

The Future of Publication

In this paper, I have presented ways of exploring knowledge production through the conjunction of film-making and ethnographic practice. This has come with a new way of presenting research findings by doing more justice to the audiovisual material and to the people involved in the research. I believe that scientific findings can escape their ivory tower without losing scientific legitimacy. Video is an excellent tool to share knowledge about scientific relevant topics to the wider public.

In recent years I have witnessed more research projects being conveyed through alternative and creative means other than the traditional peer-reviewed journals, such as creative writing, novels, interactive websites, web-videos, podcasts, and films. Creative scientific pieces attract more attention and are definitely a means of the researcher having their research results read by a wider public. The reader-friendliness also appeals to a bigger variety of readers, even across disciplines.

Mainstream media is also eager to welcome more thoroughly researched content such as scientific output, but there are still only few collaborations happening.

In the future, I assume scientists will increasingly embrace new media as the spreading of scientific knowledge becomes more relevant. As history has shown, it takes time until well-implemented academic structures such as journal publications change. Through experimenting and implementing prototypes such as the RESEARCH VIDEO tool within actual academic structures, crossing bridges between disciplines and communities might become more common; there may be more creative approaches towards the hard-dry sciences.

The RESEARCH VIDEO project’s funds end in 2020, and three years of research and development are not enough for an endeavor of this size. The project has opened many possibilities and made ideas about audiovisual scientific publications more concrete. Besides its implementation, there are several further steps, including its evaluation within a wider variety of scientific disciplines, which remain to be taken.