Introduction

The conservation-production model, implemented by the Fondo Patrimonio Natural (FPN), a Colombian environmental conservation fund, aims to protect endangered rural areas through responsible productive processes. This approach sustains that productivity can foster environmental awareness by understanding the relationship between natural resources, productivity, and social capital. We understand the latter as the capacity a community has to make beneficial decisions in order to manage their resources, fostering reciprocal and collaborative practices that place them in an advantageous position with regard to the individual approach (Durston 2001; 2002; Flores and Rello 2002).

In 2013, the Conservation and Governance (C&G) program in the Amazonian piedmont was launched by the FPN, which aimed to reduce deforestation rates through a scheme of spurs in which the protection of the ecosystem’s biodiversity (e.g. forests, natural resources) and its appropriate management (e.g. use of soil, productive practices) act as conservation incentives. Payments for Ecosystem Services (PES) are voluntary transactions in which a well-defined environmental service (or a land use likely to secure that service) is “bought” from a provider if and only if this provider continuously secures the provision of the service (Wunder 2005). The aim is to persuade farmers and landowners to improve their productive practices to make them more sustainable. Nevertheless, in the long-term, PES have proven to be economically unstable due to the instability of the resources that support payments (Gobbi, Alpízar, Madrigal, and Otárola 2006). Requiring alternatives to PES, FNP partnered with the Design School of Universidad de los Andes and conceived Proyecto Rocío, a project that attempts to strengthen knowledge in agricultural practices for environmental conservation through the implementation of information and communication technologies applied to rural financial projects.

Proyecto Rocío uses a research by design approach that explores the use of design tools to generate communities´ active participation (Buur and Matheus 2008) in which the ecosystem also becomes a player (Bosco 2006; Callon 1986). These tools purport to facilitate conversations with farmers that aim to understand territories, social capital, and relations with natural resources and also to learn from their practices and knowledge. The purpose of these tools is, therefore, to support the research process by creating tangible evidence of the conversations (Mitchell, and Buur 2010). This evidence, understood as information collected, also serves to be able to reflect upon the topics addressed. The success of the process depends on the community´s level of participation, which is, precisely, the core of our approach to social innovation.

Our discussion is based on ongoing research on a socio-ecological reciprocity system which contemplates different dimensions of value (Robbins and Sommerschuh 2016) that PES does not. It is inspired by farmers´ local practices, explained by Nardi and O’Day (1999) as information ecologies and perceptions of value besides the exchange of economic resources. We discovered other elements and interactions that are valuable for the community; we specifically focus on those that have a link with the ecosystem by introducing the concept of bio-currencies as an alternative interpretation of money-centered trades. In this way, natural resources are given a “live currency”, and farmers begin to have greater agency and participation according to their existing local resources and practices. With this in mind, this ongoing project believes that “currencies and exchange systems can be designed to connect communities to their own abundance” (Bendell and Greco 2013).

This article, hence, explores the use of participatory design tools to set the parameters to develop incentive models for environmental conservation initiatives in Colombia. It understands the role that both information technologies and rural financial strategies have in the creation of a socio-ecological reciprocity system.

Development

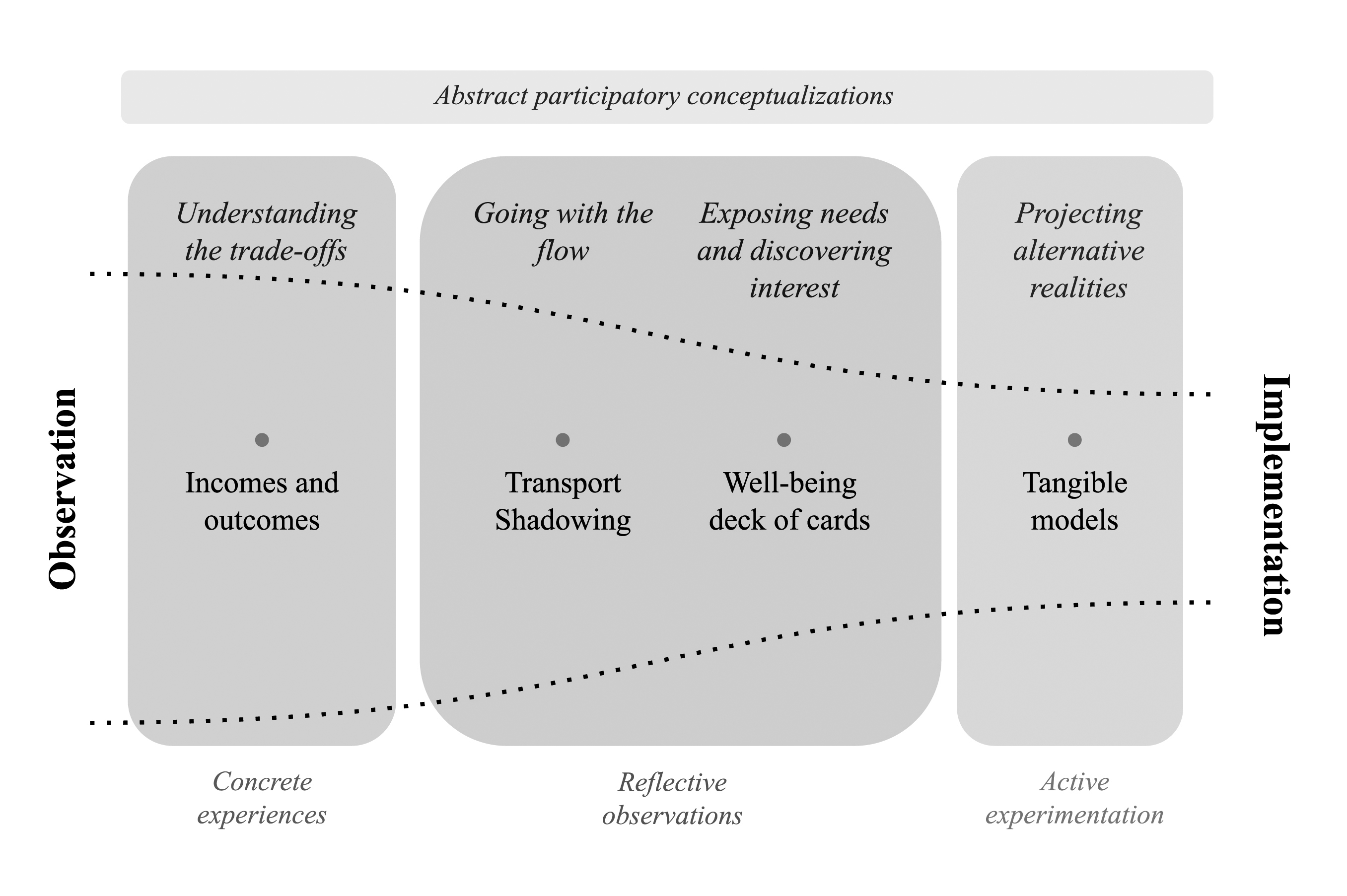

The key to innovation is to have a thorough understanding of the context (Visser, Stappers, Van der Lugt, and Sanders 2005) by identifying relationships and interactions between human and non-human actors (Bosco 2006; Callon 1986) and manifesting a disposition for learning through their practices (Gunn and Donovan 2012). Following Beckman and Barry´s (2007) innovation model, we went from concrete experiences and abstract conceptualizations of the context to reflective observation and active experimentation related to participants’ activities. In this way, we took community needs into consideration to contrast them with individual needs and build scenarios from actual practices to be able to engage in fruitful discussions rather than imposing ideas used to promote solutions (Mulgan, G., Tucker, S., Ali, R., and Sanders 2007). We integrated farmers and landowners from the communities into our processes as well as people from FPN and various other organizations to gather their expertise and to articulate opportunities that create value (Buur and Matheus 2008; Sander 2002; Sanders and Stappers 2008). In order to fulfill FPN’s main interest, we outlined an alternative incentive model that promotes environmental conservation.

The research process takes into account communities’ social, cultural, and technological norms (Easterly 2008; Nardi and O’Day 1999) together with stakeholders’ visions and experiences. We used four design tools to connect with the community (Figure 1). First, the use of maps and charts allowed us to put together collective experiences (Moore and Garzón 2010) to understand the flows that shape the community. When this was done, we focused on specific activities and interactions that we found to be more relevant to their practices (McDonald 2005). The use of ludic tangible tools allowed us to trigger interaction and to foster reflections (Mitchell, Caglio, and Buur 2013) around needs and interests related to well-being. Finally, the use of scenarios allowed us to envision alternative realities (Carrol 1999) regarding the role of monetary incentives in the proposed projects.

Understanding trade-offs

Throughout the first visits, we focused on understanding the territory and the flow of goods and resources that represent the region´s activities and capital. We used Inputs and outputs maps to identify harvests, sales, and self-consumption products. We asked 21 families from seven villages (La Granada, La Argentina, El Caimán, La Música, Filo Largo, El Porvenir, and Guacamayas) to draw a layout of their farms in a modified version of the Inputs and Outputs template (Figure 2) proposed by Van der Hammen, Frieri, Zamora, and Navarrete (2012). Once the farm was drawn, it was suggested that they mention the products it contained in order to schematize which supplies were needed and what processes were used to harvest, transform, or consume these products as well as the resultant products that were taken out of the farm. This not only allowed us to determine the kind of products that they have, but also the supplies they use, where they buy them from, and how often they buy them. When discussing the inputs, we could also learn about the kind of primary products they acquire from supermarkets, including house and personal cleaning products or nonperishable food and their exchangeable work wages. This kind of bartering, commonly known as ‘minga’, is evidence of non-monetary exchanges among different actors in the community; it allows us to enquire about the level of dependency and autonomy that each family has to obtain and manage their resources.

Going with the flow

Having a broad understanding of the flows of the products, we then followed a milk truck. This means of transport was analyzed to build a deeper understanding of the system relating to product pickups, payments, deliveries, and how people commuted. The objective of this tool was to identify the different roles that the milk trucks fulfills for the community. Depending on the season, there are between three and four milk trucks that cover the area of Guacamayas. We rode one of the trucks and documented (McDonald 2005; Ylirisku and Buur 2007) the milk collection process from the farms to the dairy factory. When the milkman collects the milk, he leaves a receipt listing the amount collected (Figure 3). These receipts represent different forms of credit for farmers that can be traded for other goods (brought back by the same truck from the local markets) or cashed in. The milkman sometimes gives certain farmers whey for free. We identify this as a way of generating value according to certain needs or interests.

Discovering needs and interests

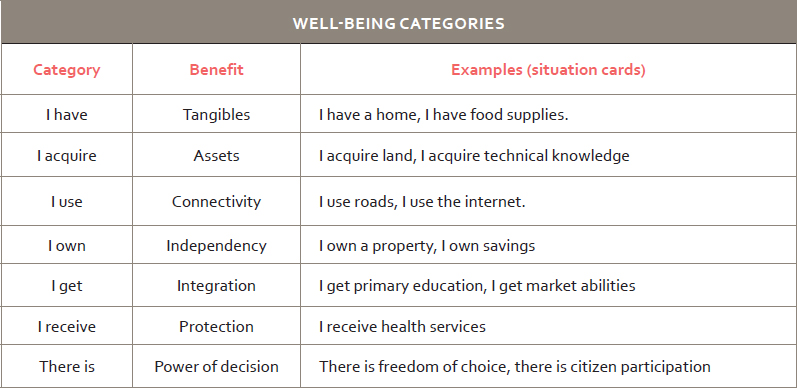

To expand understanding of the value identified by the trust networks that have been built by the community (represented by the milk truck), we developed an activity focused on well-being. Based on the compendium of OECD well-being indicators (2011), we defined eight well-being categories regarding actions that participants could reflect upon (Table 1).

Table 1.

Categories, benefits, and examples of the interpretation of the well-being indicators. Source: Adaptation from Bcompendium of OECD well-being indicators (2011).

In total, there were 42 different situation cards that were distributed according to the number of participants. In small groups (6-8 people), we handed over five cards per person; in medium-sized groups (9-15 people) we handed over four cards; and, for bigger groups, (more than 15 people) only three cards were given. When their turn came, participants could: 1) pick a new card from the remaining pile and discard an old one, 2) lock one of the cards with a wooden block, or 3) do nothing. Once satisfied with their cards and having locked them, they had to use the chosen ones to build a project that targeted a situation they were interested in (Figure 4). The objective was to start a discussion about well-being (beyond monetary resources) and see what they perceived as being beneficial. We tested various iterations while doing the activity and, although we think the tool still needs adjustments, the following discussions gave us a new perspective on the qualities and capacities of the community.

Projecting alternative realities

Continuing with the exploration of the community’s motivations and interests, we carried out two activities that allowed us to propose future scenarios (“possible futures”). These were used as tools to better understand the present and to discuss the kind of future people want and do not want (Dunne and Raby 2013). The first activity was developed in pairs. Using didactic materials, they had to describe collective project ideas while making the most important elements and the essential actors they needed to make it work evident (Figure 5). This tool seeks to identify the roles and positions that participants take when facing specific situations in simulated contexts. The second activity consisted in recreating alternative realities that speculate (Dunne and Raby 2013) about the transactional use of the forest. In this case, 15 participants watched five videos that presented different types of conservation incentives: (a) better internet access (speed and data) for each hectare of conserved forest, (b) “unlimited” access to virtual technical assistance in exchange for implementation of a silvopastoral or agroforestry system, (c) discounts on agricultural supplies in exchange for reforestation or land that is looked after, (d) lower interest rates in exchange for conserved forest, and, (e) machinery to transform products in exchange for bringing the community together to reforest. The purpose of this activity was to generate a discussion around each incentive, to validate whether the exchange (incentive-condition) was clear, and to see whether they thought the cost-benefit ratio was reasonable.

Results

The tools discussed above had two main purposes: understanding and envisioning. Maps and shadowings (Ylirisku and Buur 2007) served to help understand contexts, practices, and technologies used by the community to learn about the different interactions they have with their environment. We also identified ways in which they spend their economic resources to obtain other goods. Part of this is spent on external products (outside the territory) such as cleaning products, non-perishable products, and products that are not for growing. The remaining resources tend to be cashed in.

These villages have Community Action Boards that allow individual producers and rural families to carry out activities and achieve objectives that would otherwise be unattainable. Collective action is a social force that requires organizational and institutional methods to achieve results for the community and acts as an organism in those areas where external cooperation offers advantages (Flores and Rello 2002). For example, collective product commercialization or purchase of supplies reduces transaction costs of small producers, making them more competitive and efficient. Collective actions aim to stimulate individual efforts, in terms of community efforts, by generating mutual benefit scenarios: when the community excels, individuals also excel.

An example of one of these collective actions is the product-money exchange system that they built with transporters. We detected the use of whey as a social currency that created loyalty among the cattlemen as well as among other people who do the driver favors (e.g. the lady that gives him breakfast receives whey, even though she is not a milk producer). We consider, therefore, methods of transportation as central elements in the community network: not only because of its transportation role but also because of the social aspect relating to exchange mediators. Farmers hand over their products to the transporter, they take them to the local market where they are received and a price is calculated that becomes credit, which can be used, as requested by the producers, to buy other goods. If there is a surplus, the farmer can keep it for a future delivery or withdraw it once s/he arrives back in town. As previously explained, trust chains are the foundations of these systems. We also found other, less-sophisticated ways of collaboration including: 1) lending or sharing seeds (i.e. family members keep extra seedlings in case of future need—just like saving deposits), 2) exchanges for work (e.g. most farmers, instead of receiving a payment, exchange the time they spend in someone else’s land for time spent on their own land. As Hector Muñoz from El Caimán explains: “We work for each other, one day here and other day there; it depends on who needs help.”), 3) leasing infrastructure (e.g. one person has a “trapiche,” which is a sugar cane mill used to produce panela. Those in charge of it do not own it or the crop. Every week, two people mill the cane, extract its juice and cook it until it becomes panela. The production is divided into halves, and each party is free to commercialize it as long as they maintain an established price. This seems to be an excellent way of taking advantage of their resources, but most members prefer to have their own trapiche and production). We, hence, conclude that in these contexts, trust becomes the main currency and money, whey, shipments, and errands become transactional tools.

Exploring well-being opened a wider range of value dimensions beyond just poverty indicators or productive capacities. We unveiled parallel concepts of well-being connected to leisure, health, social relations, and relations with the environment: although our objective was to delve more deeply into their perceptions on well-being, we were only able to grasp the importance of social relationships that guarantee support from the community. Nevertheless, this gave us an input that helped explore alternative scenarios to promote reciprocal benefits involving different actors in the territory (i.e. forest, soil, and water). The appreciation they have for their land represents one of these benefits since they feel it is ‘blessed and are grateful’ if any seed flourishes. This leads us to understand that there are different factors from traditional currencies that activate community agency. As Marta Orozco from la Granada expresses: “participation is important and it is what we are doing here, sharing knowledge, it is important because we live more united.”

The construction of projects and the use of future scenarios helped to address topics related to alternative systems to promote reciprocal conservation behaviors. When asked about the practices they use for working the land, most argue that almost nothing is needed: the land is fertile, there is unlimited forest. When it came to proposing ideas for productive projects, it was expected that the community had shared interests, dreams, and goals. However, these initiatives were not always aligned with the interests or needs of everyone in the community. By co-creating projects, participants were able to discuss their expectations and balance them by including everyone’s vision. The difference in interests also happens when more stakeholders are included. We learnt from some of the participants that previous productive programs failed because expectations were not aligned. However, and without including more stakeholders, we experienced the difference when dealing with all participants. Reifying their needs and interests meant a resignification of resources (e.g. water, seeds, soil) by giving back a transactional value. Orlando Gutierrez from la Granada reflects upon the insurance that the forest represents: “We have to take care of the forest if we want to have a backup.” Even though participants were free to propose any project, most involved a natural resources mentioned above as an element that could generate value. While the community was thinking about productive projects, we began to recognize aspects that could generate a relationship involving socio-environmental reciprocity that were alternatives to PES.

Discussion

The success of implementing a financial model for rural areas does not depend on the technology available but instead on the social network practices within that territory. We used participatory design to approach this project, not because we wanted to use it to co-design an alternative currency, but because we wanted financial factors to arise by emphasizing the participation of the community to co-create individual or collective projects while taking into account natural resources. More than just co-creating new bio-currencies, our processes were focused on rediscovering local bio-currencies, and reflection was a useful tool to understand the importance of those currencies. We understood that bio-currencies belong to an earlier stage of time. We could say that they are more primitive and that primitiveness can be found in isolated rural communities were bio-currencies are still commonly used. The whey that emerged as a social currency is an evidence of this phenomenon in our research. We believe that there must be more elements like this that are used as alternative currencies. Our task was to understand their underlying meaning and perceived value of local practices, especially the ones related to production and conservation. We conclude that local currencies are means of empowering communities, as long as they respond to their practices and not to the political or economic interests of external stakeholders (Bendell and Greco 2013).

The process was far from being perfect. During the project, we encountered difficulties that were overcome through the use of design tools. Making the community part of the abstract phases of the design process makes the detailing process more complicated but strengthens the relations between the community and the research team. The variety of contexts and territories in Colombia may also complicate the process. If future research desires scalability and replicability, a similar sensitized approach will be needed to rediscover what we called bio-currencies.

At this point, what we have discovered does not yet match an alternative for PES. This is because the model needs to be defined and connected with existing systems. If productive practices cannot be ensured, any incentive to promote PES will fail. The point is not to make farmers richer but to enable activities that can improve their well-being.