Introduction

Migration processes in the south of the country have transcended time and political borders; forced displacement is a timeless phenomenon that continues to be established in the world and, particularly, in Colombia. The past five decades of armed conflict in Colombia have left more than 7.7 million displaced; only in 2018, the figure was 30,517 people, not counting the Venezuelan migrant population, which, according to UNHCR figures, amounted to more than 1.2 million in 2019.1

In the first decade of the 21st century, the population victim of the armed conflict has generally moved and remained in the main cities, giving way to precarious urban habitats, environmentally disjointed with the rest of the territory. However, another less frequent and less documented event has been the return of this victim population to their places of origin, in which the processes of land restitution and reparation to the victims have played an important role. Law 1448 of 2011,2 called the Victims and Land Restitution Law, opened a door for the accompaniment of the victim population and their access to reparation for the victimizing acts.

These restitutions and return processes are not necessarily focused on families returning to their territory of origin; in fact, the accompaniments are also carried out to communities that have settled in invaded lands (public or private), which constitutes a greater tendency than the return to the places of origin. The rate of return to the place of the victimizing event is lower, since most of the displaced population is in main and intermediate cities, where there are comparatively better basic services, as well as better access to social reintegration programs and, relatively, better income. In addition to this, returning to the territories of origin is fundamentally conditioned by the capacity of the State to provide security to the population; that is, if the victim population is recognized as a non-threatened population, they proceed to return, although this does not precisely imply to their original home of origin, since, in most cases, they do to other dwellings and, with it, to various ways of inhabiting and occupying a foreign territory upon their return.

The analysis of the two phenomena, both settling down and returning, determine that, after the exile, various forms of living are originated that, after violence and exile, converge in resilience and roots in new territories, which are adapted to vital needs. This adaptation of the territories and houses constitutes a difficulty for the quality of life of the rural population, making visible the need to propose strategies and guidelines that guide the formulation of public policies aimed at the design of prototypes and access to decent housing for the victim and vulnerable population in the rural area of the country.

This article focuses on identifying the situations of the physical space occupied by the population victim of the conflict, once they settle in a territory, after displacement and return, taking a tour of the different migratory processes that exist in Putumayo and providing an approach to the new ways of living present, when the displacement ends, not only in the places where they settle, but also when they return to the place of origin. The exposed situations allow determining guidelines and/or directives for future rural housing proposals, a housing of social and priority interest, with easy access to the victim and vulnerable population.

Methodology

Initially, to get closer to the testimonial sources and to contrast the collected documentary sources, direct observation was used, which allows us to see, listen, feel, experience the context or the observed case and, then, narrate the fact. Moderate participation with the community was made, through the preparation of open interviews and life stories, conversations, field notes, and spatial descriptions, together with a photographic record, providing a detailed account of the changing conditions of the habitat situations. The digitization of the plans and images allows the description, analysis, and interpretation of the case studies.

The type of research is deductive in nature because it allows the researcher to make inferences, based on direct observations, to describe the main characteristics of this population, without manipulating the situation.

Banishment, Displacement, and Dispossession

Migration processes in the south of the country have occurred due to different factors that took place over a long-time scale. The most documented displacements are those befallen due to the violence of the armed conflict in the struggle for control of the territory by different armed groups, starting in the 1980s. Also, several migration events were the product of invasions and dispossession, including those that native indigenous populations suffered first-hand from the extractive companies of rubber and cinchona and, later, the colonist population because of the foreign oil companies since 1950.3

Documenting the history of the migratory processes in Putumayo can be equivalent to writing the history itself of the department and the south of the country. The Putumayo Amazonian foothills have been a region of different bonanzas and extractive economies, such as rubber, cinchona, exotic skins, oil, wood, and, the most lucrative, coca, which have, at different times, caused population to come in search of land and opportunities. Additionally, its strategic position on the border made the State promote the colonization of this territory since the beginning of the 20th century. To this end, the Capuchin missions in this department had the purpose of integrating the indigenous peoples to the rest of the country, establishing agricultural and cattle colonies that encouraged the arrival of colonists from the nearby departments of Nariño, Cauca, and Huila. As a result, and with the opening of the main highways, such as Pasto–Mocoa in 1912 and Mocoa–Puerto Asís, built-in part by the Colombian-Peruvian conflict in 1932, they detonated the population of the centre of the country to settle in the wastelands near the roads.4

Another determinant actor in the territorial configurations of the south of the country was the Texaco Company, with the exploration of the so-called South Putumayo District. As oil exploration continued, a large amount of unskilled labour was required, which was supplied by the migrant population from the centre of the country.5 These colonists settled in points near the roads that the company built towards the border, to connect with the wells it had in the neighbouring country of Ecuador.6

Although the oil industry starred in different episodes of land disputes between indigenous peoples and settlers, oil exploitation produced a symbiosis between an extractive economy and a productive economy, from which the greatest developments have emerged for the western Colombian Amazon and in the consolidation of Putumayo as a border department and connection with the rest of the continent. This same fact made the department a strategic axis, first for the guerrillas of the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) and the drug trafficking cartels and, later, for the United Self-Defence Forces of Colombia (AUC) that have been present since 1980, with the idea of “liberating” the territory of the FARC and achieving control of the traffic of cocaine base paste, the most lucrative link in the drug trafficking economy.

The presence of illegal armed groups in rural areas of the country continues to have devastating consequences; in the specific case of Putumayo, the reports of the National Center for Historical Memory leave detailed records of the violent events that originate the migratory processes. These reports give a real view of how the events of the armed conflict have shaped the socio-spatial reality, revealing the crisis in rural society in Colombia.

Emptiness after exile: El Placer Putumayo

Many houses, such as the one shown in Figure 1, have had to be abandoned due to the constant conflicts and, as a consequence, slowly and gradually, they are deteriorating.

El Placer is a police inspection located ten kilometres from La Hormiga, the municipal seat of the Guamuez Valley, Putumayo. The documentation of the violence and the social crisis that the armed conflict has generated in this place is very extensive; many of the references come from the inhabitants who survived and remain in the place, but, equally, “many testimonies today are tangible and visible in the physical voids left by the violence, echoing the testimonies forgotten in the silence of time.”7

The strategic location of this town quickly turned it into a place where the FARC established an operations centre that controlled the production and distribution of the coca base paste. The incursion of the Cali cartel and, later, the Medellín cartel and the AUC gave way to the struggle for control of this territory, leaving some of the most remembered episodes in the historical memory of the conflict, such as the massacre that occurred in November of 1999 by the South Putumayo Bloc of the AUC, where the territory, became momentarily controlled by them, who consolidated a paramilitary base in this town.

Migration processes, increased to a greater extent by abandonment and exile, have configured voids and discontinuities in the urban fabric, still present in the settlements of the department. In the specific case of El Placer, many inhabitants were exiled, forced to leave their homes and belongings, and leave.8

The stripped houses were used by the illegal armed groups for different activities, such as accommodation, torture, rape, as well as for control and distribution centres of illicit substances. Sometime later and, after the continuous confrontations, these houses were looted, to extract the doors, windows, or roofs, sometimes by people who were looking to find money or hidden jewels. Some of the houses were loaned by their exiled owners to other families, to keep them preserved; however, others have not been occupied, largely due to the superstition of “seeing” or “listening” to the violent events that have occurred. Currently, many of these houses continue to be dismantled, as witnesses to the boom, rise, and decline of drug trafficking. The fact that they were not occupied again led to their deterioration, constituting a discontinuity in the populated centres hit by violence.

Spontaneous Settlements After Exile

The intermediate cities of Putumayo and other departments of Colombia have been receiving cities for the victim population, with real urgencies to establish a new place to live. In this scenario, the social factor has been added to the aggravation that these cities have less capacity to adequately manage the settlements of this new population, made up mostly of low-income families .

These irregular settlements, generally outside the perimeter of city services, have been consolidated and, over time, local governments have adjusted the service infrastructures, meeting the needs and improving the precarious habitat of these populations. However, many of these new neighbourhoods were established in disaster risk areas, such as hillsides and riverbanks, which has not been taken into account when integrating them into the design and implementation of urban planning and urban planning policies land management. This has left fatal cases such as the one that occurred in the Avenida Torrencial de Mocoa, capital of Putumayo, in 2017, or the floods on the banks of the Caquetá River in Puerto Guzmán, Putumayo, which threaten the victim population of the Jairo Casanova neighbourhood, a population that is currently executing its relocation and return plan.

Settlements such as Jairo Casanova, in Puerto Guzmán, or Nueva Esperanza, in Mocoa, have been the result of invasions of state lands, with houses made by self-construction, using transitory materials such as plastic tarps, wood, mesh, metal sheets, located on unstable lands or flooded that lack basic services. The technical ignorance in the use of materials, in the construction systems, and the poor quality of the materials, added to the economic limitations of a population, increase the vulnerability and the destructive process of the facilities in the face of any disaster. Mocoa has a population of 45,589 inhabitants and more than 50% of its inhabitants are the victim population, according to the National Administrative Department for Statistics (DANE, 2019).9

Given that Mocoa has been characterized as a receiving city for a victim population, many families — such as the 40 in 2001 — have sought new land to settle in, as is the case of the Nueva Esperanza community, which was the result of an invasion of lands belonging to the Institute for the Promotion of Energy Solutions (IPSE), after displaced persons from other regions of Putumayo, Cauca, and Caquetá arrived. The settlement has a housing and equipment area, as well as a productive area for crops and support for each family. Below is an aerial view of the Nueva Esperanza settlement.

Figure 2.

Aerial photograph of the Nueva Esperanza settlement, where the housing area is visible to the north and the productive zone to the south. Source: Own creation from Google Earth Image and Map of the National Cadastral System, Geoportal IGAC.

The impact of displacement10 in Colombia has caused both the State and non-governmental organizations to come to redress the rights of the victim community. In the case of Nueva Esperanza, the settlement has gone through different stages, including the achievement of recognition of their position in the territory to later form the victims’ association that allowed them to access the support of both governmental and non-governmental entities. With the support of entities such as the United Nations for refugees Agency (UNHCR), this and other neighbouring settlements in the same conditions have been able to form the return and relocation plan to achieve educational and community infrastructure, as well as access to public services and, primarily, achieve legalization of their properties. In this way, and thanks to inter-institutional management, the process of legalization and titling of properties for Nueva Esperanza culminated 16 years after occupying the lands, in 2017, when its inhabitants received the titles that accredited them as owners of their properties: 266 property titles, being the first titling of rural properties in Putumayo.11 This case of restitution of properties did not imply the return to the place of origin, but rather to legally remain in the place that received them after the displacement. It is important to highlight that these restitution processes are possible, thanks to the support of organizations such as UNHCR, Legal Option, Victims Unit, municipal government, among others, that coordinate their actions. Essentially, however, the structuring of the community is vital to achieving real access to the enforceability of rights.12

Inhabit the Return

The analysis of the following case exposes the tendency of the victim population to inhabit a rural territory, once they return to their territory of origin. It also allows us to take a glimpse at the difficulties, before, during, and after the return, exposing the family dynamics that configure the new ways of living, exposing the problems of rural housing and the gaps in the housing prototypes, as well as the difficulty in accessing the same.

This case refers to the experiences of the Gómez family who, for ten years, faced exile and forced displacement, and later returned to their place of origin in a home that was transformed according to their new way of life. The family initially acquired their home through the National Institute for Social Interest Housing and Urban Reform (INURBE) in 1998, the year in which the biggest confrontations for control of the territory began. Many families, like the one in this case, got along and lived with the situation. However, the pressure exerted on the social leaders worsened; in the case of the Gómez family, the father of the family was a social leader, which deepened the differences with the leaders of the paramilitary forces, causing the exile of the family of six, who moved to the department of Nariño in 2000.

At the time of the displacement, their home and belongings were abandoned; consequently, upon their return, eight years later, the family did not have a home or land of their own, so they settled in a borrowed home that they managed to acquire in 2018, thanks to their resources and subsidies from the program of land restitution of the Unit for Attention and Comprehensive Reparation of Victims.

Figure 3 shows the cycle that the Gómez family lived before, during and after their displacement and return.

Physical Spatial Analysis of the Original House

The house starts from a scheme made up of three stripes; two of them, with rooms separated by a central strip, which fulfils the articulating and social role of the house, built following a traditional scheme of the region, in which the porch is used not only in front of the house, but it also extends to the interior, in the central part; in turn, this space connects the interior and exterior of the house. In this area, the social life of the family takes place, in which they locate the living room furniture, a dining room, and hammock area. The two remaining strips make up the rooms, which are left as open rooms for their inhabitants to arrange the rooms, according to family members.

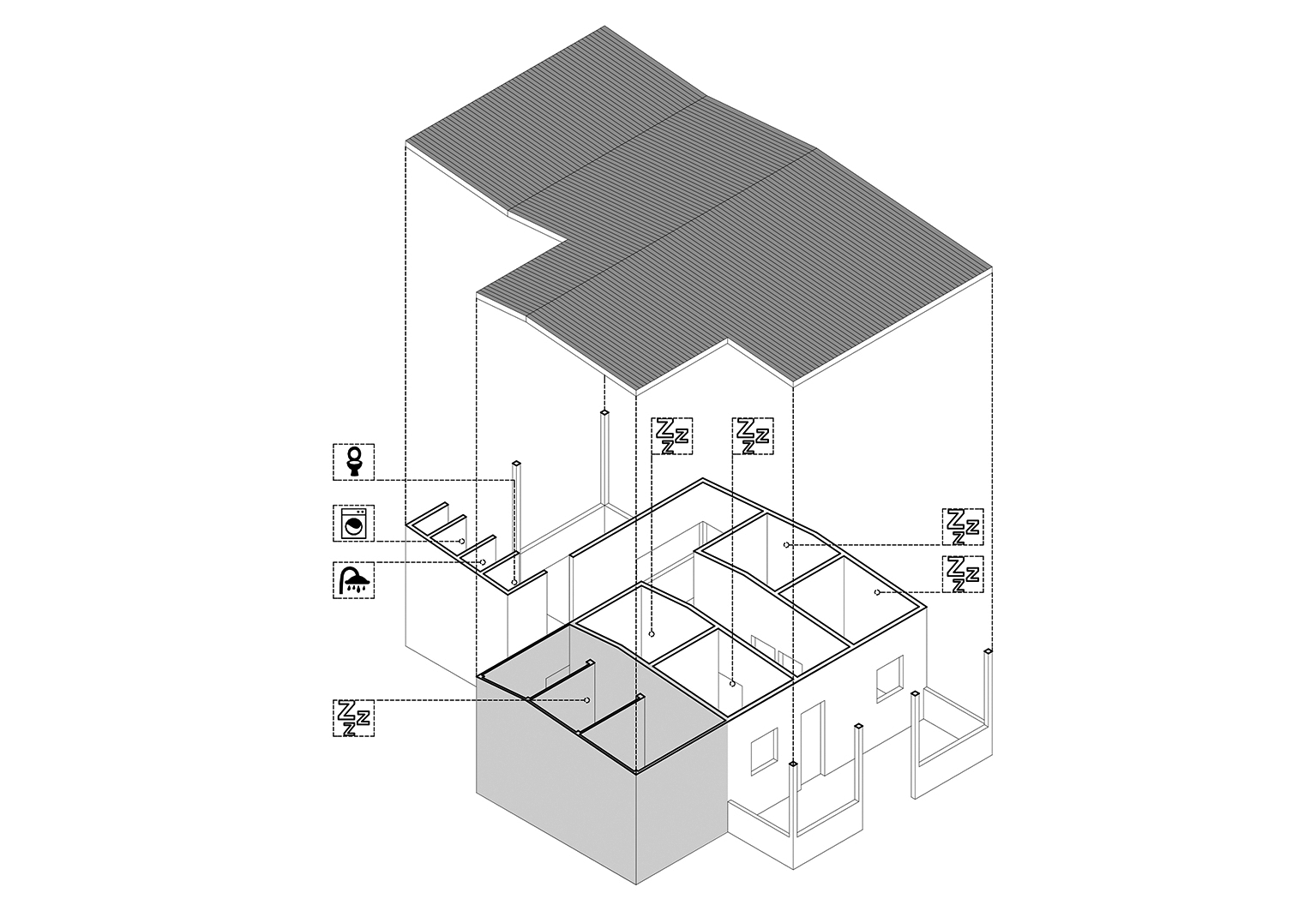

Figures 4, 5, 6, and 7, below, show the physical-spatial changes of the original house

Housing After Return: Adaptation to New Forms of Family Life

The evolution of rural housing, like the case presented, is not an isolated event and constitutes a widespread phenomenon in the rural area of Putumayo.13 Thus, it is possible to observe two general types of transformations: some internal and others external, where the first are the result of some remodelling, maintenance, and adaptations in flexible materials, such as wood or textiles, to divide spaces, create a new room or an area of work, etc.

The external transformations are done in different aspects; as a first step, the need to gain space for housing is sought and, as such, a new porch is built in front of it. However, the most particular external transformations are the spaces attached to the original home, visualizing the need for greater density, a product of time, by the dynamics of the family: The children grow up and form new family nuclei, living close to the home of their parents, due to the economic impossibility of accessing their land. These new rooms take advantage of the structure of the original house, where the enclosure walls become dividing walls between the houses.

A first semi-detached construction is made of a wooden structure and enclosure with a metallic zinc roof, to quickly delimit and establish a room. Over time, the wooden structure is replaced by a reinforced concrete column construction and block or brick enclosure; roofing materials remain in zinc tile, and the transition to fibre cement tile is seldom made. It is characteristic that the new semi-detached houses establish, over time, a language similar to the original houses, both in materiality and in the continuity of colours and finishes; however, in most cases, the original dwelling remains recognizable; in this way, it becomes a base home, where a family nucleus and new people who make up the family converge.

The case of the Gómez family is not an isolated case, but a constant in families that return or settle in a territory, after a victimizing event. Generally, rural dwellings undergo constant transformations, but, in the case of a family that returns, the fact becomes more notorious, since the base dwelling constitutes a nucleus in which the rest of the family that has returned orbits: the former members, who were six when they were displaced, and the new members, for a total of nine people. This could be due to a behavior in which (according to the testimony of the members of the family themselves) they are not able to settle anywhere else, leaving their relatives with those who suffered the victimizing act and, adding to it, their economic incapacity to access their land and homes.

In Figure 8 you can see how the house is currently.

With the above, the transformations of the dwelling after the exile are made visible. Aspects such as flexibility, adaptability, and growth overtime must be taken into account in the housing prototypes that are presented to the victim and rural population. These particularities have been raised in different urban housing studies, in which hypotheses and paths to follow for new units have been established; however, in the case of rural housing, the studies have been minimal and, in general, a clear focus is needed for the development of rural housing at the national level. Currently, the prototypes of rural housing established by the State are focused on solving the basic need for access to housing and, with some basic guidelines, an attempt is made to solve its construction in any area of the country.

In Colombia, some public competitions have explored these possibilities; Among them, the one carried out by the Colombian Society of Architects in 2019, for a prototype of productive rural housing for the southern area of Bogotá, which left among its results, tangible proposals that demonstrate the interest in proposing and providing real solutions to the problem of rural housing. Likewise, these proposals optimized to a region and a user, have made visible that a single prototype would be insufficient and would not fully cover the varied geography, culture, and society of the Colombian territory.

Therefore, the need for the academy to continue studying the possibilities of rural housing is evident, to determine its physical, spatial, and socioeconomic particularities, to integrate the knowledge of adaptation to the place of the communities and technical feedback, to encourage public policies that allow access to rural housing of social interest to the victim and vulnerable population of the conflict zones in Colombia.

Conclusions

Although two decades have passed since the inclement armed conflict in Putumayo, the inhabitants have still not recovered from the consequences. Resilience and an attitude of silence have been forging new beginnings and roots amid the armed conflict.14. After the relative calm brought by the peace accords, populations like El Placer are experiencing a new wave of violence, and territorial configurations once again respond to dynamics posed by the economy of illicit crops, which also entails a spontaneous migration of the urban population to remote rural areas, to cultivate the coca leaf, thus forming temporary habitats with precarious services or attached buildings, increasing the density of existing housing.

Advances in obtaining property titles for settlements such as Nueva Esperanza have paved the way for comprehensive, collective, efficient, and visible reparation to the victim communities in the rest of the country. The legalization of properties is advancing in Putumayo and shows the incidence that international entities have launched in the territories affected by violence, demonstrating that the empowerment of the communities themselves is fundamental for the achievement of rights and the integration worthy of the community displaced to the new realities of the territories that inhabit.

The creation of spaces attached to an existing home is not exclusive to the rural area of the south of the country; this fact is similar to the morphological transformations of urban dwellings. This search for density in the dwellings, either in height or in full occupation of the lot, increases the difficulties and vulnerability of the population, both victim and recipient. Although in rural areas this phenomenon is similar, despite not being recognized as a problem (due to a larger space on the plot), the cases studied are located close to populated centres and, over time, they will become part of peripheral neighbourhoods, without establishing adequate contact with the city.

Although government plans and programs aim to establish guidelines for the construction of rural housing, it is evident that the prototypes do not give an appropriate architectural response in their entirety, to the place. In the same way, the path of public policies that allow access to rural social interest housing is not clear and, at times, non-existent for most of the victim and vulnerable rural population. Therefore, it is necessary to analyse current homes and ways of life, to obtain the guidelines for subsequent home designs adapted and aware of the different factors in the regions of the country, converging in quality habitats, derived from a specific condition: historical and poetic of efficient and accessible rural housing.