1. Introduction: Housing as a multi-dimensional problem

This paper addresses two current questions of importance for architecture as a discipline

Which parameters can be used to conduct effective and innovative research on housing in the current planetary state of affairs? Can architecture competitions be used as a means to conduct the aforementioned research in a pedagogical context within academia?

The Covid-19 pandemic that has transformed the dynamics of human habitation throughout 2020 and 2021 can also be framed within a longer, more extended scenario of environmental crisis. Taking place at a planetary scale, this scenario has dramatically gained in both focus and intensity during the past few decades. The urgency of the present moment calls for novel means to interrogate housing as a domain where a simultaneous negotiation between the domestic, the collective and the territorial takes place.

To that extent, this text puts forward an enquiry into contemporary modes of urban habitation. This enquiry was originally articulated as a pedagogical project, delivered as a design studio unit at the Edinburgh School of Architecture and Landscape Architecture (United Kingdom). From a methodological perspective, it is methodologically grounded on the participation in a series of open architecture competitions throughout the first semester of academic year 2020-2021. The goal of this collective endeavour is to give rise to a broad, multi-faceted, speculative investigation on the operative and transformative potentials of contemporary housing design. A key thesis underpinning this body of work is the notion that the parameters affecting urban housing and habitation are — now more than ever — multi-dimensional in scope. Hence, the investigation presented in this paper attempts to capture this ‘multi-dimensionality.’ That is to say, it does not attempt to offer an exhaustive vision of the problems at stake, but rather to identify relevant directions of work to conduct more focussed enquiries in the near future.

In addition to this, the collective endeavours of design-led research that underpin the development of this paper intend to situate investigation on housing as a fundamental component of both professional and academic learning in architecture. In that sense, the academic context in which this body of design-led research was produced approaches participation in architectural competitions as a key means of production in professional practice, but also as a critical tool to tackle architectural problems from multiple, speculative angles.

2. Housing and the city. The domestic and the collective

In a recent article, Pier Paolo Tamburelli (2020) has argued that cities will not be substantially transformed in the short or medium term as a result of the Covid-19 pandemic. However, he also suggests that many of the urban habits that we have collectively acquired will remain, exerting an important influence on the domestic realm. More specifically, Tamburelli identifies the scale of local relationships (those allowing us to satisfy the needs of our daily lives within a short distance) as a key domain of future transformations.

Tamburelli’s reflection already insinuates an explicit connection between the realms of the domestic and the collective, based on the intertwining of both housing and urban design. In Van Gameren, Axel and Oosterman (2015) take this reflection one step further by noting that one cannot really exist without the other: the space around a dwelling is an inextricable component of the dwelling itself. In other words, a dwelling is not a simple distribution of square metres or a “typological puzzle” that is isolated from its context, but rather a “lived environment” that is linked to it. Thus, it is possible to posit an intimate, trans-scalar relationship between housing, city and metropolis. That is precisely the relationship that the pedagogical project underpinning this paper attempts to interrogate.

In the scalar range where the relationship between housing and its immediate environment is resolved, high-density residential developments — based on different variants of the apartment block typology — tend to endure the most of public criticism. The main source of this criticism is the provision of purportedly excessively large areas of communal space, often lacking a clear form or function (Hanley 2007, 103). Notwithstanding this, the current pandemic scenario has foregrounded the enormous impact of the aforementioned communal spaces on the wellbeing of residents, with the caveat that they must be well designed and maintained, and offer clear functionalities (gardens, allotments, meeting areas, cafés, etc.). Across the planet and throughout the development of the current pandemic, the inhabitants of high-density residential developments have used their shared communal spaces to meet one another wherever possible. Importantly, the community that emerges spontaneously when these shared areas are well-used constitutes an invaluable support network in a period where caring duties abound, encompassing children and the elderly but also those that are ill or self-isolating (Hatherley 2020).

Furthermore, throughout the past decades it has become apparent that stereotypical family structures do not constitute the only agents in the occupation of housing stock. In fact, as a format of occupation this particular structure seems to be losing its prevalent status: Other, more transitory collective structures of shared habitation are quickly gaining ground, and the existing housing stock will require a series of adjustments to fit their specific needs (Jaque 2015). Thus, housing does not constitute a ‘fixed’ programme, but rather one that is permeable and connects our private spheres with other local, social realms. This brings a key thesis of this paper to the fore: Inhabiting our home and inhabiting the city are highly intertwined endeavours. From the point of view of social relationships people do not just inhabit buildings, but also neighbourhoods and communities. As noted by Marcuse and Madden (2016, 198) these ‘places’ articulate a dense domain of social relations occurring within shared spaces.

3. The urban commons

The current socio-economic context is characterised by a financialised approach to housing: By understanding residential property as a vehicle for investment – an asset in the open market – both housing design and development are shaped by restrictive commercial criteria (Marcuse and Madden 2016, 26-50). In contrast to this marketisation of basic habitation, David Harvey (2012, 73) puts forward the notion of the urban commons: spaces where collective social relations with the built environment are established. The urban commons are shared resources, organised collectively. Critically, the term urban commons does not only encompass the physical spaces or resources being shared spaces, but also their social structures for collective governance (Harvey 2011). Besides providing services and resources, urban commons are meant to foster novel forms of social relation to emerge which, in turn, should give rise to new categories of urban commons (Harvey 2012, 67-68).

A key aspect of the urban commons is their capacity to distribute and organise functions and programmes, displacing them between the public and the private realms according to the needs and contingencies of each moment. This oscillatory organisation is described by Anna Puigjaner (2019) in relation to kitchens. She notes that our contemporary social imaginaries tend to see the kitchen as an inextricable component of any dwelling which, in turn, still appears to be associated to other social norms – for instance its character as a gendered space and its role in the productive economies of care within traditional family structures. Puigjaner argues that this limited notion of “domesticity” in relation to the kitchen is simply a social construct, which can be either reverted or reorganised. She puts forward the phenomenon of Lima’s urban kitchens as an example of such reorganisation: A traditionally domestic domain is transposed to the realm of the urban commons, forming communities and political agencies that challenge the boundaries between the public and the private, between the masculine and the feminine, and between family structures and domestic roles. Importantly, the communities formed through these shared urban commons have the capacity to enter into dialogue with other, larger scale institutions, thus leveraging the collective political agency of their participants.

4. The classroom and the office. Architecture competitions as research tools

As anticipated in the introductory section, this paper investigates the links between the domestic and the collective in relation to housing and the city, articulating this enquiry through a pedagogical project predicated on the participation in two open architecture competitions within an academic setting. In doing so, this text also posits a series of potential productive transferences between the realms of academia and professional practice, with a view to fostering intellectual speculation and experimentation through novel formats of organisation. Rather than seeking to “train” students to work in professional practice, the pedagogical project presented in this paper endeavoured to leverage its academic setting as a platform for collective research and reflection on the built environment. It follows a line of thought put forward by Cristina Goberna, Urtzi Grau and Timothy Moore (2015) who note that, throughout several historical periods, architectural experimentation has been restricted to the domain of academia. Importantly, they argue that the present situation is precisely the opposite, inasmuch as most schools focus on reinforcing the established mechanisms of architectural practice. Goberna, Grau and Moore also refer to architecture competitions as “pedagogical spaces” – that is, spaces for the intersection of the academic and professional fields are where the production of knowledge is not informed exclusively by market conditions.–

On a similar note, Federico Ortiz (2020) discusses academic involvement with architectural competitions as an alternative modality of organisation to the characteristically hierarchical organisation of design studio courses. More specifically, Ortiz refers to the development of Unit 9 at the Architectural Association in London during the 1970s as such an example of this alternative organisation. Led successively by Elia Zenghelis, Rem Koolhaas and Zaha Hadid, Unit 9 used the participation in architecture competitions to generate productive synergies between tutors and students, establishing a completely flat hierarchy in the process. In that spirit, the pedagogical experience discussed in this paper constitutes an attempt to blur the boundaries between the academic and the professional fields, while simultaneously safeguarding critical distance and autonomy of action. The latter aspect is of particular importance, inasmuch as it translates the critical value of academic contribution to the realm of professional endeavours.

5. Methodologies of collective investigation

The work discussed throughout the following sections develops as a wide-spectrum enquiry into housing and urban life, grounded on the two principles identified above: First, the development of a pedagogical experience of investigation and non-hierarchical production through participation in architectural competitions. Second, an understanding of housing as an extended system of habitation that connects the domestic domain with both the city and its territory through the development of urban commons.

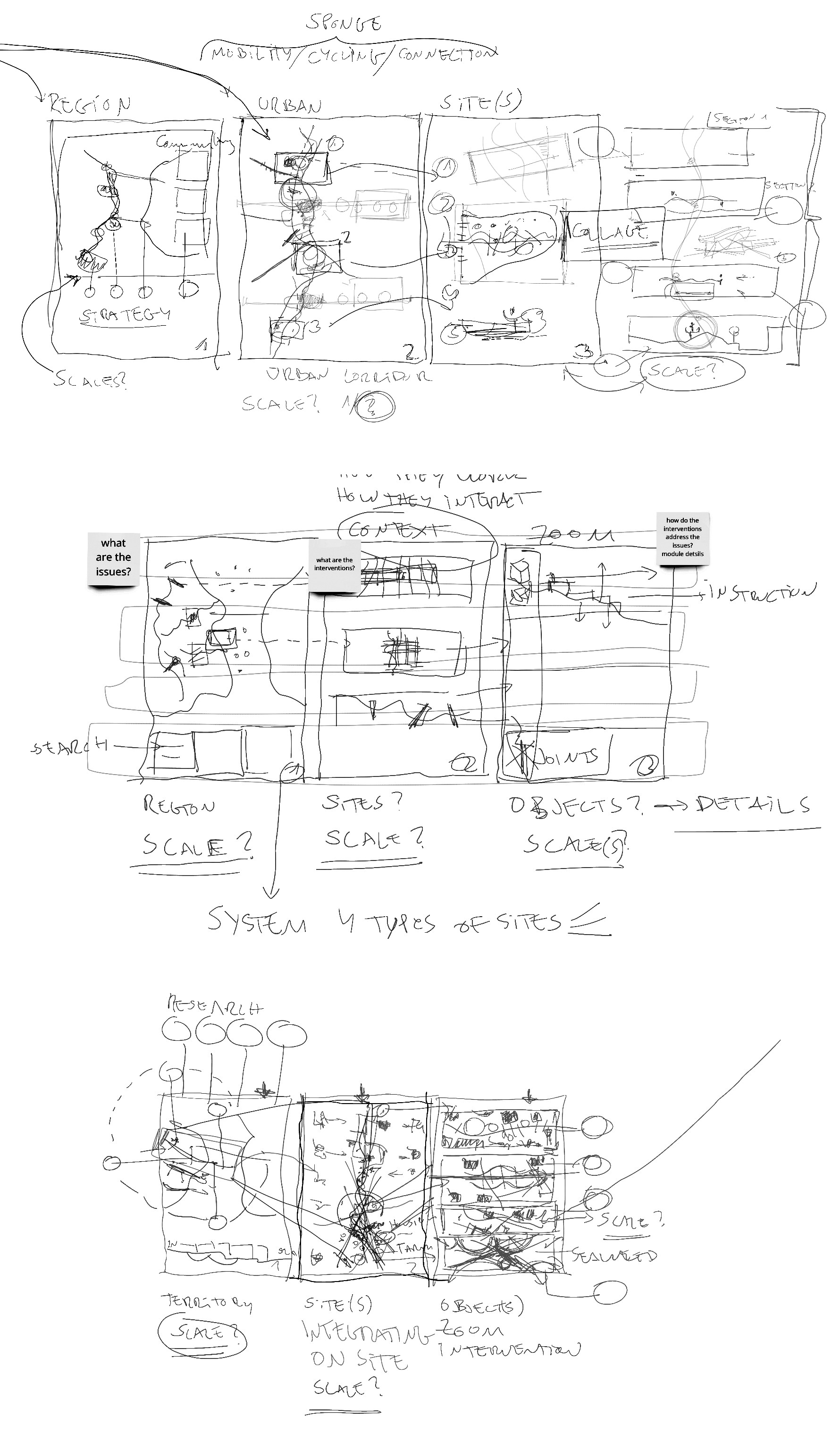

The pedagogical experience that gave rise to this collective exploration took place over a 12-week semester, in the context of a third-year architectural design studio unit composed of fifteen students and two tutors: the author of this paper and Ana Bonet Miró. The unit brief was predicated on the participation in two open international competitions, with submission dates on the fourth and twelfth weeks of the semester. From the perspective of the unit’s work dynamics, it is worth noting that all teaching throughout the semester took place remotely as a result of the restrictions stemming from the COVID-19 pandemic. In practical terms, a suitable remote teaching setup was deployed by simultaneously using two different pieces of software: A video-conference application (Microsoft Team) and a collaborative virtual whiteboard (Miro). Whereas the former reinstated the “vertical plane” corresponding to face-to-face communication between tutors and students, the latter generated a “horizontal plane” for shared work – analogous to the surfaces of work desks that we would find in a physical studio setting.

The ability of the Miro whiteboard application to foster accumulative modes of working was of paramount importance: as in conventional design development processes, multiple strata of design documents (drawings, sketches, photographs, reference images, texts, notes and diagrams) were gradually accumulated on its virtual surface. Moreover, the application made it possible to manipulate and reorganise this stratified collection “live” during weekly studio sessions (fig. 1). This “collaborative desk” was used as the main space for working, meeting and decision-making for all the student teams involved – also outside the studio tutorial hours. In so doing, it became a “live archive” of the development of the design processes undertaken throughout the semester.

6. Development and discussion of results

Both the process and the results of this pedagogical experience are presented through a curated selection of design materials. Using the studio setup described above, these materials were produced by the student teams as part of their submissions for the two architectural competitions that constituted the backbone of the studio. This exposition of the design development process also draws from the author’s own notes on the conversations that took place during tutorial sessions, as well as from the author’s own reflections on the development of the “live archive” afforded by the Miro software. All of the above is also supported by an introduction to the geographical and intellectual context of each competition.

The first competition asked participants to intervene in Penang Bay (Malaysia). This is a large territory organised around two metropolitan areas (Butterworth and Georgetown) set apart by a strait that separates Penang Island from mainland Malay Peninsula. At present, the region has one of the world’s highest ratios of population growth, as well as the highest population density in Malaysia. Its abundance of natural resources and its thriving manufacturing and technological industries have fostered a sustained, intense level of economic and human development. As many other regions undergoing similar circumstances, Penang Bay is currently suffering the ecological and environmental impact of its accelerated development, which has also led to high levels of social and economic inequality. On the one hand, Butterworth city hosts the enormous port infrastructure serving the whole region. It constitutes the main industrial and logistical hub of the Penang Bay metropolitan area and, consequently, it is strongly impacted by environmental problems. On the other hand, the urban core of Georgetown evolved from an original traditional settlement, granted World Heritage Site status by Unesco due to its urban, architectural and cultural qualities. In contrast to this, Georgetown shares its southern edge with a major Free Trade Zone that services the totality of the region. To the west, it is surrounded by the exuberant rainforest biosphere of the central Penang island hills.

The Penang Bay competition did not have a specific focus on housing design, but rather aimed to trigger reflections on how urban space could be transformed at a metropolitan scale in a scenario of technological disruption. Therefore – and using the regional context discussed above as a basis for reflection– the competition call put a strong emphasis on designing novel forms of social, economic and environmental resilience (“Penang Bay International Ideas Competition” 2020). In keeping with the focus and the ethos of this call, the pedagogical goal attained by participating in the Penang Bay competition was to initiate a collective discussion on urban transformations, identifying key vectors for the development of urban commons in the process. As part of the thesis supporting this pedagogical experience, it was expected that such vectors of development could be extrapolated to other contexts of urban transformation at a later stage in the semester. From a pedagogical standpoint, such an operation would foreground the linkage between the domestic dimension of housing and the collective dimension of the urban, as posited in earlier sections of this paper.

In order to develop the Penang Bay competition, students grouped themselves into three teams with five members each. As a first step in the process, tutors requested each team to carry out speculative investigations on five broad thematic clusters dealing with urban transformation:

Climate change – especially in relation to coastal landscapes.

Urban infrastructures, urban mobility and settlement patterns.

Digital technologies – particularly in relation to the domain of work and its attendant productive infrastructures.

Cultural and social landscapes – daily life, history and traditions.

Food, energy and their attendant distribution chains.

The design proposals developed by each of the three student teams approached these thematic clusters in different ways, often privileging some above others. The first proposal, entitled “Penang Green Spine” (figs. 2 and 3) focused on mobility as a key vector of sustainable urban transformation. Developed by Lottie Greenwood, Thomas Gumbrell, Eilidh Mckenna, Joseph Simms and Jenny Steinsdatter, the proposed intervention revolved around a long, “green corridor” of varying width. This “spine” would run parallel to the coastal line of Penang Island, connecting its regional productive infrastructures to a series of transportation links. Designed with mid-distance bicycle and pedestrian traffic in mind, the proposal sought to reframe the daily commutes of the Penang Bay populations as low-speed “habitational domains”. In doing so, the intervention consolidated large swathes of underutilised land bordering existing infrastructures into an “urban salon” for public use.

Figure 3.

“Urban collage” of linear residential developments over the “Penang Green Spine” masterplan.

The second proposal submitted (figs. 4 and 5) bore the title “A Modular Ecology” and was developed by Ellen Clayton, Eleanor Collin, Xingyu Li, Xinran Wang and Shiyu Zhang. It was based on a system of small structural cubic frames (each side measuring four metres in length) that offered multiple configurations of assembly, as well supporting different types of cladding and finishing. This system was the basis of a broad range of interventions – small in size but abundant in the number and diversity of functional programmes they supported – to be deployed in Penang Island. Each of the resulting “nodes of intervention” belonged to a basic functional type, which in turn responded to its particular setting within the ecological and productive landscapes of the region (hills, riverside, coast and bay). The finalised proposal posited these interventions as a “constellation of nodes”, each populated by different communities but also remotely connected to the rest of the “network”. By coordinating their individual, site-based development in real time, the nodes would eventually give rise to a single distributed object – which would organise the collective inhabitation of Penang Bay through social and ecological modulations.

A third proposal, entitled “Penang Bay Agritechture” (figs. 6 and 7) was developed by Coll Drury, Inka Eismar, Lee Han Liang, Jenna McMahon and Maria Wolonciej. Its design argument was grounded on the establishment of a circular economy in the region, predicated on a combination of pisciculture, algae farms and urban agriculture – encompassing the open strait, the coastal line and the inland. The attendant circular process was distributed along a series of “productive linear corridors” supported by light rail system. These corridors progressed from the inland regions toward the strait, connecting the productive programs detailed above and generating spatial continuities between coastal, urban and rural areas. All the productive components in this system were designed as light inhabited infrastructures, and thus associated with specialised in situ housing developments. In doing so, the proposal intended to stimulate the development of local economies which would, in turn, benefit from their direct connections to territorial-scale economies.

After submitting the first competition, the tutors organised a collective reflective session to identify the most important and potentially transformative themes in contemporary urban habitation articulated in the proposals. The aim was to redeploy those themes as starting points for the housing project that constituted the core of the second competition. Beyond the strategic nature of the different interventions, the discussion identified a clear general resonance with the idea of the urban commons: the three projects for the Penang Bay competition gravitated toward the creation of new spaces of collective living – flexible and developed over time – as a means to socially articulate urban life.

Subsequently – and with the pedagogical aim of supporting the research for the second competition – the tutors proposed a series of “housing studies”, drawn up individually by each student and discussed during a new collective work session on the Miro platform (fig. 8). Fifteen examples of non-conventional housing from the 20th and 21st century were studied with regard to two parameters set out at the beginning of this article: their ability to respond to non-stereotypical social structures of cohabitation, and their reinforced link between private and communal programmes. The aim of this exercise was to conceptually situate the themes explored in the first competition within scales closer to the domestic. In line with Dick van Gameren’s ideas, students were asked to represent the examples using isometric perspectives in order to emphasise their “external” mechanisms (of collective relations) rather than focusing on their typological aspects – often foregrounded in the “interior” layouts of plan documents.

Figure 8.

Collection of habitational studies, digitally annotated in Miro during a session of collective discussion. October 2020. From left to right and from top to bottom: Transformation of 530 dwellings, Bordeaux (Lacaton & Vassal); Quinta Monroy, Iquique, Chile (Elemental-Alejandro Aravena); Moriyama House, Tokyo (Ryue Nishizawa); Nagakin Capsule Tower, Tokyo (Kisho Kurokawa); Cité manifeste, Mulhouse (Lacaton & Vassal); 110 Rooms 22 Dwellings Housing Block in Barcelona (MAIO); Nemausus Building, Nîmes (Jean Nouvel); Quinta Malagueira, Evora (Álvaro Siza); Narkomfim Building, Moscow (Moisei Ginzburg, Ignaty Milinis); Terrassenhaus Berlin/Lobe Block (Arno Brandlhuber); Mother”s House, Amsterdam (Aldo Van Eyck); Ökohaus, Berlin (Frei Otto); Silodam, Amsterdam (MVRDV); Granby Four Streets-10 Houses on Cairns St., Liverpool

After completing this interim exercise, the group concentrated on the second competition, which extended the annual Taiwan Residential Architecture Award through a call for design research. The brief called for a speculative exploration of future forms of housing, responding to challenges that, albeit already existing, had been exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic: the urgent need for simultaneous protection and connection, framed within a planetary context of ecological crisis (“2021 International Residential Architecture Conceptual Design Competition” 2020). For this competition, the three previous teams were subdivided into six teams of two or three students. Although the competition rules did not prescribe any particular context or location for intervention, all six teams decided to situate their work in well-defined urban contexts throughout the design process. Whereas the proposals emerging from this process varied widely in approach and context, all of them focused on working with existing urban structures. The three most successful submissions are discussed below.

Articulated around the notion of adaptive reuse, the proposal ‘Inhabiting Seagram’ (figs. 9 and 10) – developed by Ellen Clayton and Eleanor Collin – paid attention to the emptying of financial centres in large cities as a consequence of the COVID-19 pandemic, speculating on its potential permanent effects. In the context of developed economies, the dynamics of home-based remote working have put a stop to the culture of daily commuting into the business districts and urban centres of cities. Consequently, the occupancy rates of the office buildings located in these areas have plummeted, to the point of calling into question the need for the continued availability of those spaces in the long term (“The Guardian View on Empty Offices” 2020). In keeping with this scenario, ‘Inhabiting Seagram’ explored the dismantling and selective reconstruction of an icon of modern architecture and a paradigm of the contemporary office: Ludwig Mies van der Rohe’s Seagram Building in the financial centre of Manhattan, New York. The project leveraged the potential of the building’s deep, open floor plan in order to imagine the occupation of its floors. The design deployed a system of flexible partitions around the vertical communication cores, assembled with materials originating from the partial dismantling of the façade and floor structures. Thus, the elegant vertical bronze profiles and the delicate single-glazed, tinted glass panes that characterise the external material configuration of the building were reorganised towards the interior as a luxurious system of mobile, pivoting partitions in which – to paraphrase Iñaki Ábalos and Juan Herreros (1993) – the domestic would be displaced from the immovable to the movable. In this process of dismantling and material reorganisation, the symbolic luxury of the financial world would be transposed to the domestic spheres of daily life, and punctuated by large semi-open atriums for shared use by the new inhabitants of the building.

The second proposal discussed here was developed by Coll Drury, Inka Eismar and Jenna McMahon. Their project, entitled “Housing Reframed” (figs. 11 and 12), focused on the transformation of former council housing blocks in the suburb of Restalrig Park, in the city of Edinburgh (Scotland), with a view to potentially extending its strategy to similar contexts in the United Kingdom. Such contexts are characterised by large stocks of social housing from the late 1960s, often in the form of high-density towers. These developments have received substandard maintenance over the past decades, and are often isolated among swathes of very low-density, single-family housing. Underserved by public networks, this mode of urbanisation also makes residents in these areas dependant on private transportation to reach key urban resources such as shops, schools, sports facilities and workplaces. In responding to this scenario, “Housing Reframed” made direct a reference to the building extensions in housing blocks designed by Anne Lacaton and Jean-Philippe Vassal in Bordeaux (France), as well as the “incremental housing” development by Alejandro Aravena in Quinta Monroy (Chile).

The students designed a system of extension modules, constructed with a laminated timber structure and assembled into the existing facades to add space to the dwellings and modulate their environmental response. A key innovation of this proposal was the extended use of this modular system toward the development of a range of communal facilities (a nursery, workshops and urban gardens). These new facilities occupied the roof of the blocks, their ground floors and the series of nondescript spaces that constituted their site. The facilities constituted a self-sufficient productive system, managed by the community and in a state of continuous dynamic development. In resonance with the idea of the urban commons, the project went beyond proposing a spatial or a constructive system: It also posited architecture as a collective social process. The domains of leisure, work and care would thus become part of a “new” domesticity – extended and open to the public – which would, in turn, establish novel relationships with the city. The domestic domain was extended into cyclic processes of “production” and “reproduction” or, put differently, into a cyclic process of generation and maintenance of shared social resources. “Housing Reframed” proposal was particularly successful throughout the competition process: It was selected as a finalist from a total of 328 entries, and was awarded a fifth place in the final selection round.

Finally, Xingyu Li, Xinran Wang and Shiyu Zhang’s proposal “City in the Building” (figs. 13 and 14) proposed transformation strategies for a typological model characteristic of Hong Kong’s urban fabric: the corner house. Widespread during the 1950s and 1960s, this typology is characterised by its hybrid nature, combining commercial, industrial and residential functions into a single volume with a highly flexible internal layout. Importantly, their external layout and composition of emphasises their dominant corner position within urban blocks in central Hong Kong. This typological model constituted as a particularly intense area of contact with the dense urban fabric of the city. Over time, corner houses acquired an even stronger tectonic value, emerging from the assembly of new layers over time – small structural additions, glazing variations, new services such as AC units, shop signage, etc.) In spite of its rich history, corner houses are currently falling into disuse and being gradually replaced by new, detached typologies (Yin and DiStefano 2011).

The proposal drawn up for the competition was described as a typological “reprogramming”, which could be extended to other nearby blocks as a broader urban strategy. One out of every two floor slabs were dismantled to generate a volumetric, flexible internal structure. The resulting volumes were repurposed as intergenerational housing units (encompassing children, adults and the elderly) organised by means of light, interconnected platforms located at different height levels. Internal partitions were arranged with furniture and storage systems, making it possible to adjust the dwelling layout in response to changes in the circumstances of its inhabitants. Simultaneously, a new structure was attached to the two rear façades of the building, generating a ramp that – in the manner of an architectural promenade – connected the open-plan public areas on the ground floor to a new green roof with facilities for collective use. Annexed to the traditional corner shops, this sequence of entrance and gradual ascent gave rise to new public domains on a neighbourhood scale: a set of “vertical urban commons” that would make the most of Hong Kong’s density. This reprogramming operation generated a wide gradation of habitation conditions – negotiating the domestic with the collective – plus a large-scale, cumulative public intervention.

7. Conclusions and remarks

The contribution of this paper develops around two distinct areas. The first one pertains to an operational domain: the work establishes the guidelines for a strand of professional practice predicated on entering architectural competitions within an academic, pedagogical context. The discussion developed in previous paragraphs sets out a methodological approach to undertake this endeavour, and outlines how this methodology can be translated across different contexts in the form of local research problems. As it quickly becomes apparent, there is some tension between the systematic character of the academic studio brief and its attendant pedagogical experience (which, to a certain extent, is presented as being independent of the specificities of the competition briefs) and the need to generate contextualised responses to the two competition calls in specific social, geographical and cultural terms.

The second key contribution is the confirmation of the initial thesis of this paper by means of the design research processes that have been presented in previous sections. The detailed discussion of these processes demonstrates that – paradoxical as it may seem – the realm of the domestic is intimately linked to the realm of the collective: future housing will be – more than ever – articulated in a close relationship with the city. Transfers and links between the two domains abound: urban commons are incorporated into the domestic universe, while dwelling simultaneously expands into the spaces of collectivity. Housing cannot be disassociated from the endeavours of daily life in which it is subsumed (work, care, leisure, health, etc.) inasmuch as they articulate both its spatial and temporal organisation. As unequivocally manifested in the three proposals for the second competition presented in this paper, future housing appears to us as a social process in a state of continuous development. Critically, this process is formally articulated through superimpositions to existing structures, rather than ex novo developments. As a consequence of this, their design is methodologically approached as a series of adjustments and adaptations – which can nonetheless be extremely ambitious and radical. Finally – and as all the competition proposals shown in this paper demonstrate – it seems clear that future housing can transcend project sites in a number of different ways: It is intimately connected to urban infrastructures (physical or immaterial) that link the domestic sphere to economic, social and environmental processes on a planetary scale. More than any other typology, future housing develops in a radical inter-scalar space that negotiates the domestic with the metropolitan and the territorial.

As the ongoing pandemic scenario has taught us, isolation – in any of its modalities – is not a sustainable lifestyle choice. On the other hand, achieving urban resilience depends on our ability to trigger transformative processes that link local and collective inhabitation together. Thus, a key question arises in regards to the development of our urban future: what and how much are we willing to share?