Introduction

Around Keushu’s anthropic lagoon in northern Peru, lie the funerary and ceremonial structures raised by pre-Hispanic cultures throughout almost 1500 years not only to host and honor their ancestors, but for them, the forefathers, to guard their descendants and to wield their power and presence over the territory; its resources; and, most importantly, its water.

The purpose of this article is to present and acknowledge the rich and complex relationship between water as an economic and sacred resource in the landscape, and funerary pre-Hispanic architecture in Peru’s Ancash region. We also aim to establish a space for reflection, presenting an architecture whose poetic gestures, as we will see in the text, contrast with the decisions that shape our current built environment.

Understanding some of the aspects of pre-Hispanic architecture and its relationship with its surroundings, invites us, as architects, to re-think the paradigms under which we practice architecture. It also invites us to think about the true scope of architecture as a tool for us to build and give meaning the world around us.

Even though this article does not present the full complexity of a culture so different to our own, discovering an architecture which, thanks to the dead and the gods dwelling in the landscape, guarded and protected a resource as valuable socially and economically as water, shed light on a singular culture with a complex worldview that integrated the social, cultural, economic, and spiritual aspects of life.

The analysis of the funeral structures at Keushu begins by presenting the symbolic characteristics of its surrounding landscape, understanding the sacred dimension behind mountains, rocks, rivers and lakes, a landscape in which funerary architecture built the relations of power over water as a vital economic resource. Later, we observe the association between water and mortuary architecture by studying the structures’ typological variations over time and highlighting punctual characteristics such as orientation or visibility over the territory.

The connection between sacred landscape, location, typologies, orientation and visibility, reveals a rich and complex architecture with poetical features that can merge not only the symbolic and sacred aspects surrounding it, but also the day-to-day activities of the community related to these structures.

Worldview in Andean Cultures

“Todo cuanto existe en la naturaleza está lleno de vida […] Los nevados, los cerros, la tierra, los árboles, el mar, las lagunas, los ríos, las estrellas del cielo, forman un conjunto de energías vivientes llamadas colectivamente Kawsay.” (Barrionuevo 2011, 23)

Pre-Hispanic cultures in Andean regions were communities with a complex, animistic, and a highly symbolic worldview. The natural territory they inhabited contained, to a great extent, the elements that helped them conceive their surrounding universe; therefore rocks, mountains, and water were given symbolic features that linked them not only with divine figures, but also with the community’s most important ancestors, whose energy inhabited each constituent part of the sacred landscape.

Narratives about the Andean Spanish conquest, archeological records, and oral tradition throughout generations, describe a close relationship between natural landscapes and funerary rituals practiced by Andean communities that exposed how ancestors and the main territory’s resources were bound by these practices (Valverde 2008). The most prominent mountains, source of the water that nourishes the territory, were and are known today as Apus or Apukunas, guardians and lords of the lands lying before them and where the most important forefathers of the community lived (Allen 1988, 41). The Huandoy or Huascaran snow-capped peaks, visible from the Keushu archeological site, were considered two of the most important Apus in the region, understood either as deities or as mutual ancestors of great importance that guard everything laying in front of them. (Fig. 1)

Apus represented the masculine energy of nature, complemented with the feminine energy of Pachamama, the Earth goddess and one of the most powerful beings in the Andean belief system. Apus, Pachamama, and many of the sacred landscape elements were considered beings with a well-defined personality that interacted continuously with the mortals that constantly sought their favor and protection (Barrionuevo 2011).

Water that springs from Apus feeds the region’s rivers, lakes, and lagoons, known in some cases, as Pacarinas, places where the soul of men and women emerge and where they return after death to the primordial unity from where they were born. Mircea Eliade (1961) said: Returning to water is returning to the “undifferentiated mode of life”; returning to the origin where we all come from. Pacarinas and its relationship with water seems to be deeply related with the presence of the dead on the symbolic and physical Earth of the living. North American archeologist George Lau (2016) describes the interior of the tombs as Pacarinas that “sheltered and cultivated the vitality of ancestral beings,” and where group communities emerged and originated.

Considering that the tombs that sheltered the mummified ancestors, or Mallkis, were placed next to rivers, lakes, or crops, it doesn’t seem coincidental that Mallkis were considered seeds or eggs that fed and nourished the earth where they were returning.

Acknowledging some of the sacred elements of landscape, Apus, Pacarinas, Pachamama, or even Mallkis, gives us a context and meaning to understand the architectural decisions that shaped the built environment we are about to study, as these elements were a continuous and fundamental influence over the pre-Hispanic mortuary architecture.

Water and funerary built environment

Funerary practices in the pre-Hispanic context had a symbolic, economic, and social importance, fundamental not only to strengthen the community’s collective memory over time, but also the daily activities of appropriation and procurement of resources (Herrera 2005). According to archeological records and stories about the Spanish conquering in the Americas, practices where mummified ancestors took part in rituals involving their extraction from the tombs as a symbolic and cultural ceremonial act were not only common, but also a demonstration of power and entitlement over valuable resources that were claimed through the built tombs that hosted the Mallkis in specific strategic places in the territory (Herrera 2007; Valverde 2008).

In this second chapter we will explore how funerary architecture in pre-Hispanic Andean cultures was closely linked with the process of appropriation and procurement of water based on two principal strategies: First, typological transformation of architectural structures over time in relation with their visibility and presence on the landscape; and second, the orientation and location of tombs regarding water bodies such as rivers, lakes, or snow-capped peaks.

The Chullpas appear

In Keushu and the central northern region of Peru, we find three main mortuary architectural typologies built in different time periods showing us some of the intentions behind the design and construction decisions at the time they were built. The evolution from underground funerary structures to above-ground and highly visible towers, suggests a series of systematic strategies not only to symbolically integrate the landscape elements, but also to show power and sovereignty over a resource. Let’s explore the main characteristics of these typologies.

Subterranean Tombs are the oldest typology between the three types of structures. Chronologically they are located at the Early Horizon period and the Early Intermediate period, between years 0 and 600 CE (Valverde 2008; Herrera 2005; Lau 2011).

These are underground spaces, with long excavated corridors about 3 meters long in some cases, less than a meter wide, covered on its sides by small rocks, and which gave access to a variety of lateral small chambers where ancestors lived. (Fig. 3)

Under Rock Tombs were spaces, as their name suggests, under big rocks over three meters high, guarding a single semi-underground chamber with areas reaching 7 square meters in the case of Keushu. The rocks over the tombs were, and are today, highly visible in the landscape, but can be easily confused with other rocks and tombs around them. (Fig. 4)

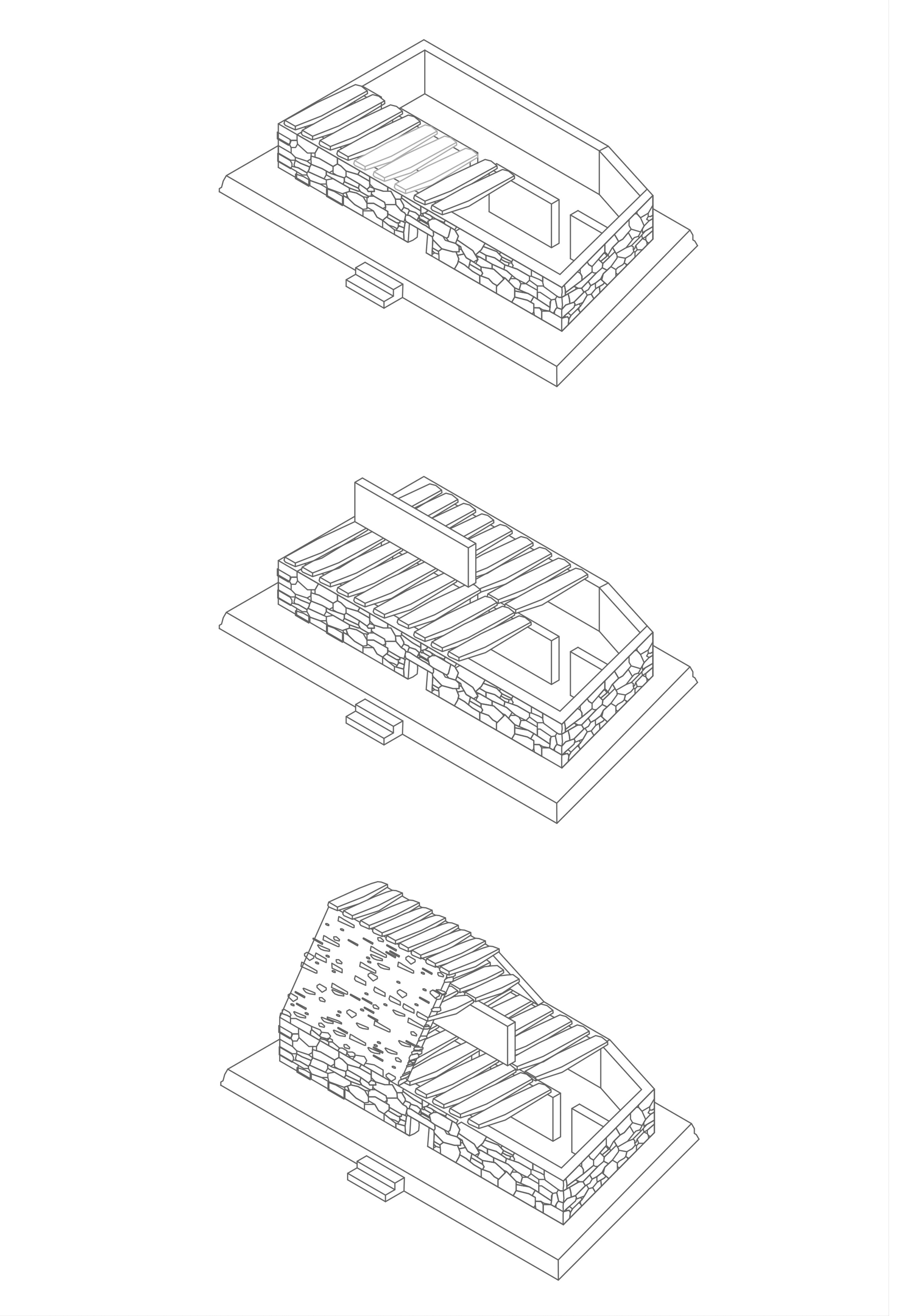

Finally we have Chullpas, one or two floored towers built with small, medium, and large overlapping flagstone slabs, with one or more principal accesses and with an interior divided by masonry walls enclosing the different mortuary chambers. At Callejón de Huaylas, chullpas usually have a rectangular base (Herrera 2005); however, in other Latin American regions, semi-circular-based, partially attached to mountains or rocky surfaces Chullpas have been found (Rivet, 2020). At Keushu, for example (Fig. 5), long stone slabs placed over the shortest side of the rectangular based chullpas set the foundations of the superior floors and its internal walls. Chullpas’ roofs can be gabled, slightly convex or flat (Mantha and Malca 2004), finishing off a structure that is usually raised on natural or artificial mounds of earth (Fig. 6), a feature of the Wari influence in the region, as pointed out by Peruvian archeologist Juan Olvera (2016).

Most of the chullpas in the Ancash region were built during the Middle Horizon (700-1200 A.D.), and their appearance marks an important milestone in Andean architecture by indicating a change in strategy in the design of funerary structures, a fact that has led to different and varied hypotheses about their incursion into pre-Hispanic architecture (Herrera 2007; Valverde 2008). However, many of these theories concur in that chullpas appear as a mechanism to accentuate visibility and appropriation over the territory and over its most valuable resource, water (Herrera 2005, 2007; Lau 2002; Valverde 2008).

Both in the Chinchawas region and in the Callejón de Huaylas, chullpas emerged as the predominant architectonic typology towards the year 800 CE suggesting their appearance as a need to render visible the monuments built for the ancestors as a means to mark and appropriate the territory against external pressure (Lau 2002; Herrera 2005). Lau (2002) highlighted the variations in ceremonial and architectural patterns through the analysis of ceramic and anthropomorphic stone pieces linked to the arrival of the warlike Wari culture during the Middle Horizon. The author discusses the need to make funerary buildings much more visible in order to successfully claim rights over vital resources and land endangered by the arrival of Wari people. (Fig. 7)

Thus, the change in the architectural paradigm of the Andean peoples, who sought to make their ancestors’ homes more and more visible, reveals a growing interest in empowering their ancestors and demonstrating their capacity to appropriate resources that were becoming increasingly scarce and valuable. Underground and under rock tombs made the way for chullpas, structures that were visible for the living, but also built for the dead in strategic locations that amplified their view over land and water.

Landscape and Architecture

In 1970, anthropologist Arthur Saxe proposed eight hypotheses about funerary practices of various cultures around the world. Perhaps the most resounding of these hypotheses within anthropological and archeological fields is Hypothesis eight, in which he suggests that the arrangement of the funerary structures in the space “attain and/or legitimize by means of lineal descent from the dead,” the appropriation of “crucial but restricted” resources. Saxe based his theory on the study of how the tombs of dead were arranged in cultures far removed from our case study such as Papuans or the Ashanti culture in west Africa.

In his studies on the Recuay culture, Lau (2016) demonstrated, that Saxe’s hypothesis also applied to Andean pre-Hispanic communities, understanding what Saxe meant with “crucial but restricted” resources, as the relationship between funerary architecture, water, and agriculture in the region.

Thus, Lau explained how ancestors kept having an active role over the daily activities of the living, affecting affairs such as grazing, farming and irrigation processes. The word Mallki, for example, was not only used for naming the mummified ancestors; it also meant seed, egg, young plant, or tree, suggesting therefore that locating them, as we saw previously, next to crops and land, physically and symbolically improved their fertility over time.

Agriculture and grazing were the region’s main economic activities (Valverde 2008). Thus, water became indispensable for life in Callejón de Huaylas, where it was limited on the rocky and most elevated parts of the mountains, and where external factors, such as the arrival of the Wari or the periodic climatic difficulties, gave it a vital value that had to be protected by the living and the dead.

Citing historians and anthropologists Maurice Bloch and Jonathan Parry, Lau suggests that the “Funerary practices focus on that resource which is culturally conceived to be the most essential to the reproduction of the social order” (2016, 175). He explains that in different parts of Ancash (Chinchawas, Pueblo Viejo, or Nuevo Tambo, for example), chullpas were always oriented towards crop fields and the irrigation systems that supply them. They were usually located in rocky areas where water may be scarce and difficult to distribute, instead of being erected in peripheral locations, where their presence could have more clearly demarcated the boundaries of the territory from other cultures that put their sovereignty at risk. (Fig. 8)

Herrera (2007) reinforced this thesis by studying groups of chullpas in the Callejón de Huaylas, where most of the structures are placed on the western side of the Callejón, over the Cordillera Blanca, from where the water that irrigates the mountain range flows. There, the principal necropolises of Keushu, Awkismarka, and Colltapac, are directly linked and oriented towards the streams and water bodies flowing from Huandoy snow peak. On the other side, on the dryer Cordillera Negra, even though Herrera identified a lesser quantity of chullpa groups, these were always oriented towards the mountain range’s main water bodies. At Kunkash for example, he found a group of 26 chullpas grouped next to the farming site of the Acolló valley, and positioned towards the course of the Washka river.

If erecting visible chullpas established the presence of a community ascribed to their common ancestors on the territory, orienting them towards resources and sacred points on the horizon allowed the ancestors and the gods of the landscape to exercise their presence over the daily affairs of the living. In the northern communities of Peru, these gods and ancestors were always, in one way or another, bound with the water that allowed life.

Finally, let us see how the spatial strategies mentioned above materialize in the sacred landscape of Keushu, where the funerary structures are organized around a lagoon built and planned by the inhabitants of the sector to facilitate irrigation and water distribution to the surrounding arable land, and which are always in direct relation to the Huandoy and Huascarán snow-capped mountains, the Apus that guarded and protected the lagoon and the region.

Keushu

The archaeological site of Keushu is located in the Ancash region in northern Peru and on the Callejón de Huaylas, made up by the Cordillera Negra to the east (4,000 masl), and the Cordillera Blanca, that thanks to its snow-capped peaks reaches 6,760 masl, to the west (Fig. 9). The water supplying the central lagoon and the farming fields surrounding it comes from the Huandoy (6,395 momsl) and the Huascarán (6,768 momsl) snow-capped peaks.

The lagoon is located in the geographical Suni region, set between 3,000 and 4,000 masl. It is characterized by its mountainous topography and by the large number of big rocks which moved during the last glacial era, over a hundred thousand years ago. During the first months of the year, the climate is wet and rainy, reaching temperatures of -1 degrees Celsius, while the last months of the year are dry and warm, with temperatures oscillating between 10 and 20 degrees Celsius, making water scarce during this season. Also, the site is located far from the Santa river, the main water body of the Callejón de Huaylas, which makes its procurement and distribution complex. This is why water became so important and valuable in these elevated regions. (Fig. 10)

Research and results

The Keushu archeological site is divided into seven sectors (A-G) that facilitate its analysis and the spatial organization of its structures, among which we can find residential, productive, ceremonial, and mortuary buildings, the latter in the form of subterranean tombs, under rock tombs, and chullpas. (Figs. 11 and 12)

During the research period at Keushu, orientation, visibility, and the architectural typology of the funerary structures were analyzed, together with other features that allowed us to understand the close connection between the most visible and elaborated tombs and their orientation in relation to the sacred landscape elements bonded with water and its cycle. (Fig. 13)

Figure 13 shows the analysis results for the orientation of 90 of the 105 tombs at Keushu. Subterranean tombs were excluded from the study, as their access, mostly vertical, made the orientation analysis unmeasurable.

Results show that most of the tombs, regardless of their typology, were even oriented towards the snow-capped peaks on the horizon, to the rivers, waterways, or to the central Keushu lagoon. However, this was partly due to Keushu’s unique geography, as the ladders where most of the under rock tombs are located, directly face and surround the central lagoon, the rivers, and the mountainous horizon, thus always directing the structures’ access ways towards these relevant points of the landscape. Accordingly, the results show great heterogeneity in terms of the orientation of under rock tombs, as some face the snow-capped peaks; others the waterways; and others still, the central lagoon.

In contrast, structures whose orientation could be arranged and designed (chullpas), show more rigorous and clear results regarding their orientation, directing their access mostly towards the mountains in the horizon, where Apus Huandoy and Huascaran stood. (Fig. 14)

Thirteen of the seventeen analyzed chullpas were oriented towards the snow-capped peaks on the horizon, regardless of the sector or location in the Keushu complex. Among the group of thirteen structures, chullpa TB1 stands out as the biggest and highest chullpa of Keushu, presenting a volume visible from almost every point and perspective at the site, as it was additionally built over a high mound of earth. (Fig 12.)

After studying the tombs’ visibility in space (Fig. 15), and given the particular geography at Keushu, both the under rock tombs, located mostly on the hillsides surrounding the lagoon, and the chullpas, are highly visible from the perspective of the living, standing at any point on the site. The chullpas differ, however, in that their typology stands out and contrasts with the rock tombs that easily blend into the mountainous landscape. (Fig. 16)

The final results of the orientation and visibility studies demonstrate, in conclusion, that the chullpa typology structures at Keushu were built mostly in order to orient their accesses directly towards the landscape’s water bodies, such as the lagoon, the waterways, rivers or the Apus on the horizon, and to erect prominent tombs on the landscape visible from almost every perspective of the site, making clear in the space their intention to appropriate and protect the hydric system that fed the land and crops vital for the communities inhabiting this place. These decisions shaped a poetic architecture that based its design on the bond between the living, the dead, and the gods of the landscape.

Poetic Architecture

At the beginning of this article, we described poetic architecture as being capable of integrating a community’s daily social, economic, and cultural aspects with the sacred and primordial dimension we all harbor as a natural side of our humanity. An architecture that thanks to its relationship with water was able to reveal the power of the dead and the symbols of nature veiled in the landscape.

The word poetry comes from the Greek word Poiesis or Poiein, meaning “to do” or “to reveal” something. This doing means to unveil the Aletheia, or truth for the classic Greeks; a truth that connects us human beings with our primordial reality, with our origin; a truth that in some ways, reflects our essence and the essence of the things surrounding us, which is originally the same (Zambrano 1993). Poetic gestures occur on this physical plane we inhabit, for talking about origin and symbols does not exclude the physical and material reality surrounding us. Both water and architecture are in this case necessary for it to occur.

Architecture at Keushu was poetic because it revealed the sacred hidden dimension of things around it, of the snow-capped peaks, the lakes and rivers, and of the gods and ancestors that dwelled within them (Barrionuevo 2011). It was poetic because thanks to the tombs built at Callejón de Huaylas, we can understand some aspects of the worldview of a community that saw water as a strategic social and economic resource, so important that it was guarded and protected by the most important ancestors that ensured the survival and sovereignty of their descendants. In brief, poetic because, with a constructive and spatial gesture, it integrated culture, economy, mortals, ancestors and gods, thanks to the bond between water and architecture. (Fig. 17)

Building strategies such as orientation, location, visibility, or typology in relation with water, established an architecture that allowed the community behind it to connect with the world and to somehow understand the universe around them. How does architecture help us to understand our universe, our world, and its resources today?

It is worth reflecting on the architectonic paradigms and parameters that rule our built environment today, maybe colder in comparison, with gods missing and illegible symbols. A world headed only towards economic results, depleting our resources and forgetting the fundamental side of human beings that Heidegger (1971b) defined in his quadrature as the harmonic and poetic dwelling of men on earth, as mortals, under the sky and before the gods. (Figs. 18 and 19)