Since ancient times, water management has determined the way of inhabiting both rural and urban land. Water management, and specifically hydraulic engineering, has been part of territorial planning from the Middle Ages until today. This management was decisive in the colonization of America and is decisive today, due to the challenges generated by increasing extreme weather events. Currently, cities grow over underground grey infrastructure that injects and evacuates water, accelerating its passage. This infrastructure, comprising pipes, cement components or waterproof materials, implements a monofunctional view of this resource. This view privileges the quantity and quality of water over the systemic values inherent in its ecological function.

Systemic visions of water management are not unusual. For example, in the Bogotá savannah, indigenous settlements inhabited the territory based on water management (Rodríguez Gallo 2019). Appropriate water management allowed to feed the population; therefore, it was the basis for pre-Hispanic settlement’s subsistence. From the Middle Ages to the eighteenth century, water management in Europe maintained a systemic approach within its technical resolution. Hydraulic infrastructure always functioned as part of a system of canals, reservoirs, and other constructions to conduct water. Antoine Picon (2015) cites Charles D’Aviler’s Dictionnaire d’architecture civile et hydraulique, where hydraulic engineering appears as a specialisation in architecture.

The dialogue between architects and engineers has been decisive in shaping the urban space. During the last decade, engineers have led innovation in water management, with the study of new management infrastructures using a holistic and systemic approach known as water-sensitive cities (Wong y Brown 2009). Gradually, this approach to water management has permeated the planning and implementation of sustainable urban drainage systems (SuDS) projects and other blue-green infrastructure in various cities in Australia (Department of Water 2005), United States (Philadelphia Water Department 2019; Dylewski et al. 2014), United Kingdom (Construction Industry Research and Information Association and Woods Ballard 2015) and Spain (Comissió de SuDS de l’Ajuntament de Barcelona 2020). However, implementation is still incipient in the world and even more so in the Latin American context. SuDS are most often identified in parks or spaces associated with road infrastructures, such as pathways, medians, and tree pits (Mostafavi y Doherty 2016; Castro-Fresno et al. 2013). However, it is rare to find urban development, renovation or improvement projects that involve alternative water management to greywater infrastructure.

In the last thirty years, the intensity and frequency of rainfall have increased, especially in urban environments (Zhang 2020). This directly affects the number of flood events, caused partly by the waterproofing of the urban soil. Such waterproofing increases the speed of the surface runoff and prevents the filtration of water into the subsoil, intensifying erosion (Arnold y Gibbons 1996).

In rural environments, 50% of the water infiltrates the soil, 40% evaporates and 10% becomes runoff. In urban environments, these percentages are drastically reduced to 15% infiltration, 30% evaporation and 55% runoff (Philadelphia Water Department 2019). The amount of runoff water from an urbanised environment is 45% higher than that of a rural area. From this perspective, the increasingly recurrent events of extreme rainfall affect cities greatly since urbanised areas are more prone to flooding.

The design paradigm in our cities aims to evacuate water from the inhabited spaces to the nearest body of water. The water that runs through streets, squares, pathways, and roofs in our cities is driven by grey infrastructure towards open-air bodies of water. This often occurs in the channelisation of streams.

The principles of water-sensitive cities respond to this problem. Its objectives are to plan the city articulating it with its hydrographic basin, to propose water management that maximizes the provision of ecosystem services and to include water management as part of community life (Wong y Brown 2009). Other authors highlight the need to reduce the risk to public health by mitigating possible effects caused by floods and maintaining the cultural values of the intervened environment (Department of Water 2005). In cities such as Bogotá and Mexico City, it has been identified that the water-sensitive cities approach is beneficial for alternative water management, due to its inclusion of technical, ecosystem services and communal strategies (De Urbanisten & Autoridad del Espacio Público 2015; Torres et al. 2019).

This article shares three experiences within intermediate-scale urban projects that implement a water management strategy based on SuDS. This selection followed the review of 89 projects in Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Peru, Colombia, Mexico, India, Indonesia, Vietnam, and Spain. The three case studies relate to a set of architectural buildings. The authors focused on Latin American projects, aiming to apply the research outcomes to this context.

The three projects are of an intermediate scale because this allows implementing treatment trains or SuDS typologies that work together to drive, retain, filter, or treat water. This scale requires spatial and technical resolution regarding relationships between buildings, road infrastructure, and public space, as well as water supply and sanitation services. During the design development, the projects’ authors tended to maximize the multifunctionality of the water management infrastructure, fulfilled additional functions as public space and areas of ecological connectivity, and provide ecosystem services. In one of the projects, the community was involved in formulating the intervention’s strategic framework. Additionally, these are innovative projects in their multi-scale understanding of water management from the basin to the technical proposal in situ.

This analysis seeks to explore if it is possible to reduce the effects of urbanisation on the water cycle by using new urban and architectural design strategies applicable to the Latin American context. It seeks to identify if these design strategies can be applied to an intermediate scale and what would their spatial conditions be.

Implementing blue-green infrastructure is still incipient in Latin America. This results from poor integration between urban design and planning with ecosystemic and community-building responsibilities. This separation is reflected in the guild’s lack of knowledge of alternative water management technologies and general or incomplete regulations on the subject.

Green infrastructure concepts, SuDS and intermediate scale are introduced in the section below. Subsequently, the three case studies are presented and analysed according to their use of fundamental principles regarding water-sensitive cities and their spatial strategies. Finally, the conclusions are drawn.

Blue-green infrastructure

The projects presented in this article are examples of implementing the so-called blue-green infrastructure, necessary to achieve water-sensitive cities. This type of infrastructure is an alternative to grey infrastructure, which uses elements such as pipes, walls and boxes built in cement or concrete. The blue-green infrastructure is characterised by managing the water resource from natural elements such as gravel and vegetation.

According to Fletcher (2015), blue-green infrastructure involves decentralised and systemic water resource management. The main objective is to manage water sustainably while benefiting ecological connectivity, maximising the provision of ecosystem services, and building community.

Among the technical solutions identified as blue-green infrastructure is green infrastructure playing a role in water management. Yet, is not limited to it, as there are green roofs, permeable surfaces, rain gardens, bioretention areas and artificial wetlands. Many of these technical solutions are catalogued as SuDS. However, for a SuDS to be classified as a blue-green infrastructure, its technical solution must allow ecological connectivity, provide ecosystem services, and build community.

Sustainable urban drainage systems

SuDS’ objective is to contribute to the hydrological regime of a site by regulating its quantity and quality of water, amenity, and biodiversity (Construction Industry Research and Information Association & Woods Ballard 2015). Frequently, these systems are projected as complements to grey infrastructure, using techniques that infiltrate, filter, store and evaporate water.

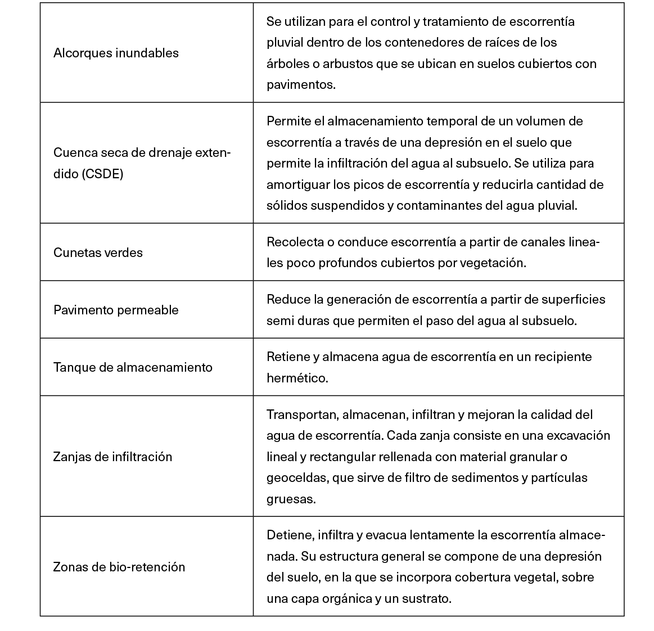

Given the variety of terms to name concepts related to SuDS, the definition for SuDS found in the Colombian Technical Standard NS166 of 2018 was used here. This definition specifies that SuDS “are a set of solutions adopted in an urban drainage system to retain rainwater, if possible, at its point of origin without creating flooding problems and minimising the impacts of urban development regarding quantity and quality of runoff” (Empresa de Acueducto y Alcantarillado de Bogotá 2018, 5). illustrates the SuDS typologies established in this standard.

Table 1.

Typologies of sustainable urban drainage systems. Source: created by the authors based on Empresa de Acueducto y Alcantarillado de Bogotá (2018).

Besides the seven typologies in the NS166 standard, this article studies artificial wetlands implemented in some of the analysed projects. According to article 1 of the Ramsar Convention wetlands are “areas of marsh, fen, peatland or water, whether natural or artificial, permanent or temporary, with water that is static or flowing, fresh, brackish or salt, including areas of marine water the depth of which at low tide does not exceed six metres.” (Secretaría de la Convención de Ramsar 2016, 9). Artificial wetlands are SuDS that mimic the functioning of a natural wetland.

Intermediate scale

The intermediate scale refers to urban-scale interventions that include medium-term execution times. Frequently, it assumes a relationship with what is known as an urban project, which, according to Manuel de Solá-Morales Rubio (1987), transforms the road layout and the building fabric while translating the essence of the place. According to Solá-Morales Rubio, urban projects are defined from five points: 1) they have an impact that exceeds their scope of intervention; 2) the uses, users and types of communal spaces proposed are complex and varied; 3) they correspond to a medium-term operation scale; 4) they prioritise the construction of the city over the construction of the architectural object, and 5) they link to the public sector, which participates in the proposed investment or collective use. For this article, an intermediate-scale project has at least four of the five points raised by Solà-Morales Rubio. The relationship with the public sector is excluded because projects of private or non-governmental origin were found to meet the fundamental characteristics of the urban project.

The following sections illustrate how three intermediate-scale urban projects meet the four points mentioned while involving a blue-green infrastructure proposal. In the above cases, the blue-green infrastructure complements the traditional layout composition or its urban project fabric.

Can Cortada 2008-2013 (Barcelona, Spain)

Location

The project is on the outskirts of Barcelona (Spain). This area features unconsolidated urban land, altered by transformation or urban regeneration. It is a 100% public initiative that includes a complex of 200 residential units. It comprises an area of approximately 2.64 ha (26400 m²), where SuDS are part of the rainwater management within pathways, squares, and roads. The public space and SuDS design was by the architect Roberto Soto Fernández. The housing design was by Martí-Miralles, Arquitectes (Figure 2).

Spatial description

Through an earthwork strategy, basins and mountains were created, allowing an easily walkable surface with multiple routes and surrounded by gardens. The proposed streets are not monotonous corridors with lines of trees; on the contrary, they are spaces where trees and gardens dynamically appear (Figure 3). The pedestrian surfaces and all the gardens and tree pits are multifunctional. These provide shaded spaces for contemplation while retaining, stopping, and infiltrating water (Figure 4). The proposed public space functions a as blue-green infrastructure supported by SuDS.

Water management description

Using infiltration basins, permeable pavements, tree pits and green ditches, the proposed design allows most rainwater management on the surface. This strategy significantly reduces the construction of underground networks. According to the project’s authors, these measures achieve a 50% peak flow reduction in the sanitation network and a 44% reduction in the volume of water injected into the sewer (Perales Momparler y Soto Fernández 2004).

Most of the gardens are infiltration basins. These collect runoff water from the surrounding impermeable areas. Under normal conditions, this system allows water to infiltrate the subsoil, through a drainage pit. In extreme rainfall conditions or with excess water, it provides a sink that overflows into the traditional sewer system. The basins form a network. Therefore, small basins can overflow into a larger basin, so there are no isolated operating typologies.

The quality of the infiltrated or overflown water was also considered. The constructive design of each basin comprises a first layer of recycled gravel in contact with the natural terrain, a second layer of the same material wrapped in a geotextile and, finally, a layer of grey gravel or an alternative plant substrate that supports a vegetation cover (Figures 5 and 6).

Regulations

Implementing this green infrastructure was the result of policy advancements in the European Union (EU), Spain, and the Autonomous Community of Catalonia. According to Castro-Fresno et al. (2013), the EU formulated the Water Framework Directive 2000/60/EC (Parlamento Europeo y Consejo de la Unión Europea 2000) with the aim of improving the quality of this resource. The EU Floods Directive EU 2007/60/EC (Parlamento Europeo y Consejo de la Unión Europea 2007) was also created at a continental scale to establish the criteria for flood risk assessment and management. At the national level, Spain has Decreto Real (Royal Decree) 1620/2007 (Ministerio de la Presidencia 2007), which defines the legal terms for the reuse of treated water, and Decreto Real 400/2013 (Ministerio de Agricultura 2013), which regulates planning based on the study of the water basin. At the local level, there are the Urban Planning Code of Catalonia (Comunidad Autónoma de Cataluña 2021) and Decree 21/2006 by Generalitat Catalana (2006), which establish architectural design guidelines on environmental sustainability. These standards illustrate the constant planning and regulation development necessary to improve the integration of water, urbanisation, and other processes.

The project mimics the water functions prior to urbanisation and generates multifunctional spaces to promote permanence and habitat for local fauna. However, the authors did not find actions aimed at building water-sensitive communities or didactic or social management strategies within the project to teach people about the functions of these spaces beyond enjoyment and landscape. Nonetheless, this project demonstrates the possibility of implementing these strategies within the Catalan regulations and shows how the designer’s intentions can become a seed for urban projects with low impact on the water cycle.

Maiporé 2010 (Soacha, Colombia)

Location

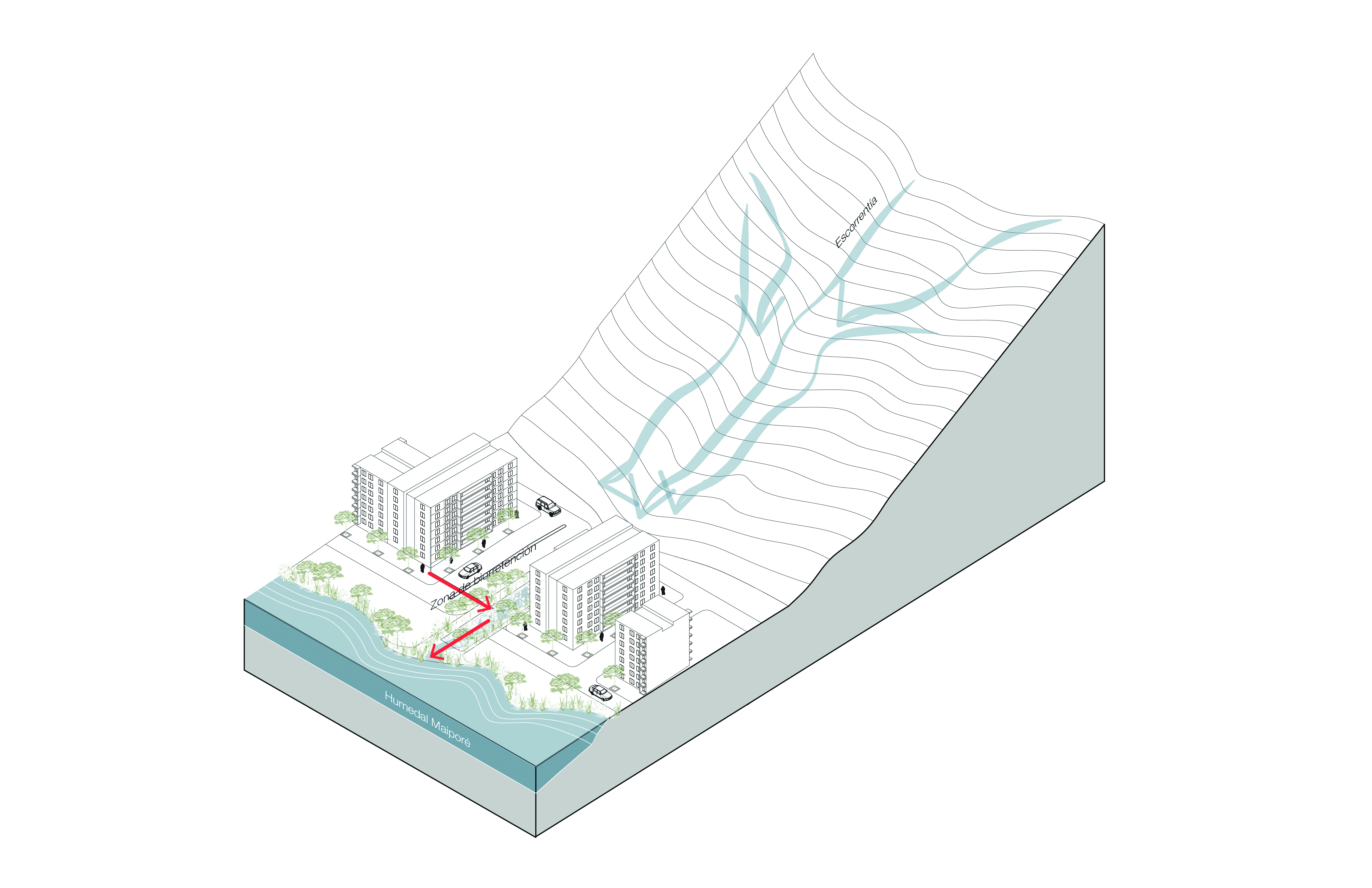

Maiporé is on the southern border of the municipality of Soacha, southwest of Bogotá (Colombia). Maiporé was a private initiative by the developers and construction company, Fernando Mazuera & Cía. The project comprises an area of 183 ha for the construction of approximately 18000 new housing units, local schools, medical centres, shopping centres and a cultural centre. It uses bioretention areas for rainwater management, in which infrastructure occupies approximately 19 ha of the entire site. The urban design is by architect Andrés Martínez (Figure 8).

Spatial description

Maiporé proposes an urban structure that includes a variety of spaces with vegetation that look like forests for pedestrian. These vegetated spaces, which may be labelled as parks or green areas, are actually bioretention areas that filter, infiltrate and conduct rainwater from the roads and other impermeable areas of the project. They are often attached to sports or educational facilities, or their proportion is reduced to make way for pavements, parks and meeting places. The Maiporé wetland stands out within this network of vegetated spaces, as a pre-existing space that was respected and integrated into the urban project. This wetland receives the water from the bioretention areas, allowing a water cycle similar to the one functioning before urbanisation (Figures 9 and 10).

Water management description

According to the project’s author, the proposed design allows retaining 100% of the runoff water from roads, pathways and hills bordering the project on the eastern side. 40% of this water infiltrates, and the remaining 60% is directed to the wetland. The system has a 3620 m³ peak rate of runoff.

The bioretention areas form a continuous structure that receives the surface waters coming down from the hills and the runoff from roads and pathways. This water is temporarily retained and gradually filtered through biological processes carried out by the upper layer of vegetation. Water that cannot be infiltrated is led to the wetland, where it infiltrates or overflows into the Bogotá River.

The bioretention areas are surrounded by stone gabions that function as both filters and barriers. These areas comprise a gravel bed and granular material that allow water to be infiltrated and stored permanently. The vegetation layer above includes trees, shrubs, and grass species. The soils of the pre-existing wetland were not modified, so they operate alike prior to the urbanisation (Figures 11 and 12).

Regulations

At a national level, projects such as Maiporé must comply with Decree 2811 of 1974 (Presidencia de la República de Colombia 1974), which regulates water management and use. This standard specifies the allowed conditions to discharge into natural water bodies, the rights for water use and the water supply and sewage requirements for new urbanisations. Regarding water discharged into a wetland, Colombian Decree 1076 of 2015 (Ministerio de Ambiente y Desarrollo Sostenible 2015) regulates the management of the country’s protected areas, including lagoons and wetlands. Additionally, the Technical Regulation for the Drinking Water and Basic Sanitation Sector (Ministerio de Vivienda 2017), stipulates the requirements that water management infrastructure must meet. This is the only regulation that directly mentions SuDS, demanding the implementation of this technology for new urban developments where land cover is modified. Finally, the National Climate Change Policy (Ministerio de Ambiente y Desarrollo Sostenible 2017) provides guidelines to articulate territorial entities aiming to adapt to climate change through multi-scale actions.

In descending order, the next administrative level for projects built in Soacha is related to the water basin where the entire municipality is located; in this case, it is the Planning and Management Scheme for the Bogotá River (POMCA). This regulation articulates various government entities and policies that affect the Bogotá River basin. The POMCA proposes a vision for the river’s future that requires implementing programs and incentives at various scales and in several municipalities, including Soacha and Bogotá (Corporación Autónoma Regional 2019).

The projects and guidelines proposed in the POMCA must be reflected in the Land Management Plan (POT) for each of the municipalities within the river´s basin. In Soacha, the POT corresponds to Agreement 46 of 2020 (Alcaldía de Soacha 2000). This plan does not have any specific requirements for water management with alternative technologies, flood prevention or runoff quality improvement.

In Colombia, guidelines to implement SuDS and other blue-green infrastructures at national level are incipient. However, there are no clear implementation policies in local legislation. In this context, Maiporé stands out because it implements an alternative runoff management system that is still not mandatory by local legislation. It implements a blue-green infrastructure system at an intermediate urban project scale and without using grey infrastructure for water management.

As in Can Cortada, community-building strategies and increasing awareness of the water cycle are incipient here. Although in Maiporé there are signs explaining the cycle, they have been vandalised, as noticed during a visit to the project in February 2022. Given the magnitude of the intervention, the social strategy must be addressed from various fronts (additional to visual communication) including a participatory strategy and greater dissemination. This may be included in the project’s next phases. This case study shows that it is possible to implement alternative water management solutions, despite the lack of local regulation, which is encouraging in the Colombian context.

Água Carioca 2012-2017 (Rio de Janeiro, Brazil)

Location

Figura 13.

An incremental approach to the sanitation of Guanabara Bay. Source: Photomontage by Ooze.

Água Carioca is a research and design project for wastewater treatment and management in Guanabara Bay, which includes several municipalities, such as Rio de Janeiro (Brazil). This bay is very polluted by direct wastewater discharge from various types of urbanisations, including favelas or informal neighbourhoods.

The firm Ooze, led by Eva Pfannes and Sylvain Hartenberg, provides a multi-scale and decentralised vision of basic wastewater sanitation. The proposal includes both the individual building and the neighbourhood to consolidate a basin strategy. With an almost utopian vision to clean Guanabara Bay, the project specifies the artificial wetland areas needed to treat the wastewater for a school (approximately 1800 m²), a 15-house complex (approximately 1500 m²) and the entire bay (approximately 6 km²). Additionally, it includes a pilot project in the Botanical Garden of Sitio Burle Marx, supported by the municipality of Rio de Janeiro and the Creative Industries Fund NL. This pilot demonstrates the project’s technical feasibility, as well as its various cultural dimensions (Figure 14).

Spatial description

The decentralisation proposal is based on the collection, treatment, and reuse of wastewater for a four-people housing unit. The unit’s treatment system includes a septic tank, an artificial wetland, and a storage tank to filter, treat and collect wastewater before it is reused or evacuated to the bay. This unit can operate independently or as a cluster so that several dwellings share the same artificial wetland. The size of each wetland changes according to the number of integrated dwellings. Using housing as a basic unit, Ooze implements three theoretical exercises at different scales, in three different favelas around Guanabara Bay: 150 houses in the favela Morro do Salgueiro, 600 houses in the favela Morro da Formiga and 20000 houses in the favela Rio das Pedras. Each implementation exercise responds to the topographic and morphological conditions of the site. Morro do Salgueiro and Morro da Formiga are on sloping terrain, while Rio das Pedras is on flat ground.

Despite these topographical differences, the three proposals provide spaces for human enjoyment in the same areas of the water management infrastructure. Morro do Salgueiro has places to walk and stay that look like linear parks, where paths and gardens intertwine to host people, vegetation, and water. In Morro da Formiga, leisure and meeting areas face the streams and natural rivers, which have clean water thanks to its previous treatment in artificial wetlands. In Rio das Pedras, a linear park is proposed along the river mouth and a network of linear public wetlands. In the three proposals, the artificial wetlands are not isolated small-scale elements, but rather variable-scale components that configure the landscape and public space.

Visibility and water management education are central to this project. In the pilot project, didactic elements were proposed to explain water processes and states, using colour and graphic information to address a non-specialised audience. In addition to defining the shapes and colours of the project’s elements, the pilot was presented together with the wastewater management strategy of the entire Guanabara Bay. The exhibition was held in Sitio Burle Marx, featuring academic, public and community actors (Figure 15). There is also a website for the project illustrating its different phases and elements (Ooze 2017).

Water management description

The pilot project at Sitio Burle Marx is the initial unit for the water treatment cycle to clean Guanabara Bay. This unit has two water storage tanks, a septic tank, and an artificial wetland. It collects rainwater from the roofs and uses the drinking water from a traditional water system. The water collected on the roofs is stored in an outdoor tank connected to an irrigation system or the artificial wetland. Water from the traditional system is connected to the building’s drinking water taps. The toilet drainage system is connected to a septic tank for treatment prior to its discharge to the artificial wetland. After removing contaminants through a biological process in the artificial wetland, the resulting water is of sufficient quality to be reused in toilets and irrigation or discharge into natural bodies of water.

An artificial wetland is a construction capable of containing a constant water mirror in a vegetated area with species that withstand humid environments. This aquatic environment allows the presence of oxygen, algae, and bacteria capable of removing the decaying organic compounds in the water. The pilot construction comprises a layer of gravel coated with a geotextile, then a layer of sand for the roots of the vegetation growing on a top layer of loose gravel. The design team estimated that between 1.5 to 2 m² of artificial wetland is required to treat the wastewater from one person (). The proposals for Morro do Salgueiro, Morro da Formiga and Rio das Pedras were based on this estimate.

In Morro do Salgueiro, the artificial wetlands are branched, grouping water treatment every 15 houses on average. These treat the water of approximately 750 people in this favela. In Morro da Formiga, the wetland system is similar to the one described above. However, the artificial wetland branches are linked to a central natural body of water. The Morro da Formiga system can treat water for up to 2700 inhabitants (Figures 17 and 18). In Rio das Pedras, the wetland grouping is more evident, as they are arranged by strips in the neighbourhood’s peripheral areas. It is estimated that this system can treat wastewater from 90,000 inhabitants.

Regulations

For the case study in Brazil, national regulation was found regarding sustainable water management. However, at the state or municipal level, no details to implement these national parameters were identified. According to Gomes-Miguez and Pires-Veról (2017), the precedent for SuDS regulation in Brazil is Federal Act 6766 of 1979 (Presidência da República do Brasil 1979). This law provides basic parameters for urban development, such as the necessary conditions for urbanisation, the minimum infrastructure for urban development, and the guidelines for flood risk areas. The authors found a later law in the city’s statutes (Presidência da República do Brasil 2001), which establishes general urbanisation parameters regarding the right of each inhabitant to access a healthy, productive, and recreational city. This standard specifically refers to the regulatory requirements to promote the improvement of the city’s environmental conditions, the protection of environmental assets, and the regulatory instruments that each municipality must implement. Subsequently, Gomes-Miguez and Pires-Veról (2017) mentioned the Manual de drenaje urbano sostenible (Manual of sustainable urban drainage) published in 2004 by the Ministry of Cities. This specifies, for the first time, fundamental principles for the alternative management of the city’s drainage, as well as a rainwater management plan to finance projects. Finally, Law 11445 of 2007 established national guidelines for basic sanitation. The water management vision in this law introduced a new role for sustainable drainage systems because it integrates notions of water retention, detention, and treatment (Presidência da República do Brasil 2007).

According to the Água Carioca’s authors, the project was not instigated by knowledge of the regulations found by Gomes-Miguez and Pires-Veról, which demonstrates a weak link between national and municipal regulations. Despite this gap, Gomes-Miguez and Pires-Veról identify additional projects using SuDS, highlighting one in Guanabara Bay.

The effort to integrate environmental, design and community building factors in this project is evident. It is striking that this type of precedent has not been capitalised to change regulations in Rio de Janeiro and encourage decentralised water management strategies to improve Guanabara Bay’s environmental quality. However, there is hope for urban architects and landscapers to implement similar strategies, despite the local regulation gap.

Analysis of water-sensitive cities

This section relates the case studies with the three principles of water-sensitive cities: cities articulated with their water basins, cities that provide ecosystem services, and cities that comprise water-sensitive communities (Wong y Brown 2009). summarises the compliance of each project with these pillars and strategies used by designers.

Table 2.

Comparison of the design strategies used and their relationship with the pillars of water-sensitive cities. Source: Created by the authors based on Wong and Brown (2009).

All three cases are articulated with their water basins. In Can Cortada, rainwater is retained and infiltrated as it was before the urbanisation was built. This concept is achieved by integrating water management on pathways and roads. In Maiporé, the conditions prior to urbanisation are also recreated, since water continues to be conducted from the surrounding hills to the natural wetland through retention, filtration, and infiltration areas. Água Carioca uses a multi-scale strategy to address the basin, aiming to improve the water quality of the final receiver (Guanabara Bay).

The provision of ecosystem services is also a constant in all three projects. Can Cortada services include support, provision, regulation, and culture. The water basins provide leisure services in a variety of subtle ways, through heterogeneous circulation spaces, allowing pleasant views, and increasing the number of vegetated areas. This vegetation contributes to climate regulation and provides food for the local fauna. Maiporé increases the provision of ecosystem services (thanks to the generation of new vegetated areas in the bioretention areas) and allows pedestrian connections with the hill. Água Carioca offers ecosystem and cultural services, as it increases the amount of vegetated area and creates additional aesthetic value. It also provides cultural services through its educational design quality and community articulation.

Regarding the contribution to the construction of water-sensitive communities, Água Carioca stands out for its periodic relationship with the community and other actors (Figure 19). This included interviews and teamwork that resulted in the formulation of a didactic project. It teaches visitors about the process of water collection and treatment using graphics and coloured paintings over the water management structures (Holcim Foundation 2017; Ooze 2017). Likewise, it established people from the community responsible for the project maintenance. It also has a website that explains the pilot’s connection with the proposed vision to clean Guanabara Bay and demonstrates the project’s ability to dialogue with diverse actors over a long period of time (Ooze 2017).

In Can Cortada and Maiporé, the relationship with the community takes place during the project’s use phase. Maiporé uses signs to explain the operation of bioretention areas, but the authors did not find participatory activities where the infrastructure function and benefits were described to the neighbours (Figure 20).

Conclusions

The intermediate scale is suitable for building water-sensitive cities because it has sufficient dimensions to 1) implement various types of blue-green infrastructure, 2) articulate a project with its water basin, 3) provide diverse spaces for ecosystem services and 4) facilitate community involvement in the formulation, development, implementation, and maintenance of the projects.

The scale of Can Cortada, Maiporé and Água Carioca comprises various SuDS types, articulated as treatment trains. For example, in Maiporé, the bioretention areas along the roads are connected to an existing wetland. Can Cortada features permeable pavements, floodplains and green ditches that are articulated according to the water needs. Água Carioca built artificial wetlands and storage tanks for wastewater reuse. The intermediate scale is also flexible to propose sufficient water management zones while creating a landscape project or a multifunctional area that people enjoy. In this context, it is worth noting the landscape impact of the bioretention area in Maiporé, the sunken gardens in Can Cortada, and the artificial wetlands in Água Carioca.

It is also in the intermediate scale where the necessary community integration appears. Água Carioca clearly demonstrates its mechanisms and benefits. The didactic quality of this project’s formulation, design, dissemination, and subsequent pilot implementation stands out. In Can Cortada and Maiporé this interaction is not so evident. However, in countries such as Colombia, implementing intermediate-scale projects – classified as partial plans – require socialisation and integration within the receiving communities. These could be scenarios to teach about the water cycle and the blue-green infrastructure functions within this cycle. They could be the first steps to transforming the water-urban environment paradigm.

It is also at this scale that the community can engage in management and maintenance strategies. They can monitor and set off early warnings about malfunctions or infrastructure requirements. Perhaps, neighbourhood associations are the ideal channels to communicate with those in charge of consolidated urban space maintenance, whether they are public bodies, private entities, or the community itself.

Blue-green infrastructure involving SuDS is presented here as a design strategy that can function as a necessary hinge between various disciplines to achieve more permeable cities and transform the relationship between urbanisation and the water cycle. This would be an option to change the scale of an entire city through the transformation of a cell.