How to Cite: Lara, Fernando Luiz, Fernando Luis Martínez Nespral and Ingrid Quintana-Guerrero. ""¡Let art subvert its reduced canon!". Interview with Andrea Giunta Dearq no. 36 (2023): 9-15. DOI: https://doi.org/10.18389/dearq36.2023.02

“Let art subvert its reduced canon!”. Interview with Andrea Giunta

Fernando Luiz Lara

fernandoluizlara@gmail.com

School of Architecture

University of Texas at Austin, United States

Fernando Luis Martínez Nespral

fernando.martineznespral@fadu.uba.ar

School of Architecture, Design and Urbanism

Universidad de Buenos Aires, Argentina

Ingrid Quintana-Guerrero

i.quintana20@uniandes.edu.co

School of Architecture and Design

Universidad de Los Andes, Colombia

The work of Andrea Giunta has been central to the decolonization and overcoming of canons in art's history and criticism. In this interview, Giunta discusses the process of establishing her own categories, along with other reflections about the legacies left by the Verboamérica exhibition, its impact on subsequent Latin American modern art research and the academia and market's reactions. Giunta also explains how power relations have stopped and revealed projects hidden by the “official” historiography. She closes with an interpretation of Latin American recent history and the present challenges in pursuit of renewal because “change in drops” is no longer a solution.

Keywords: decolonization, Latin American thought, historiography.

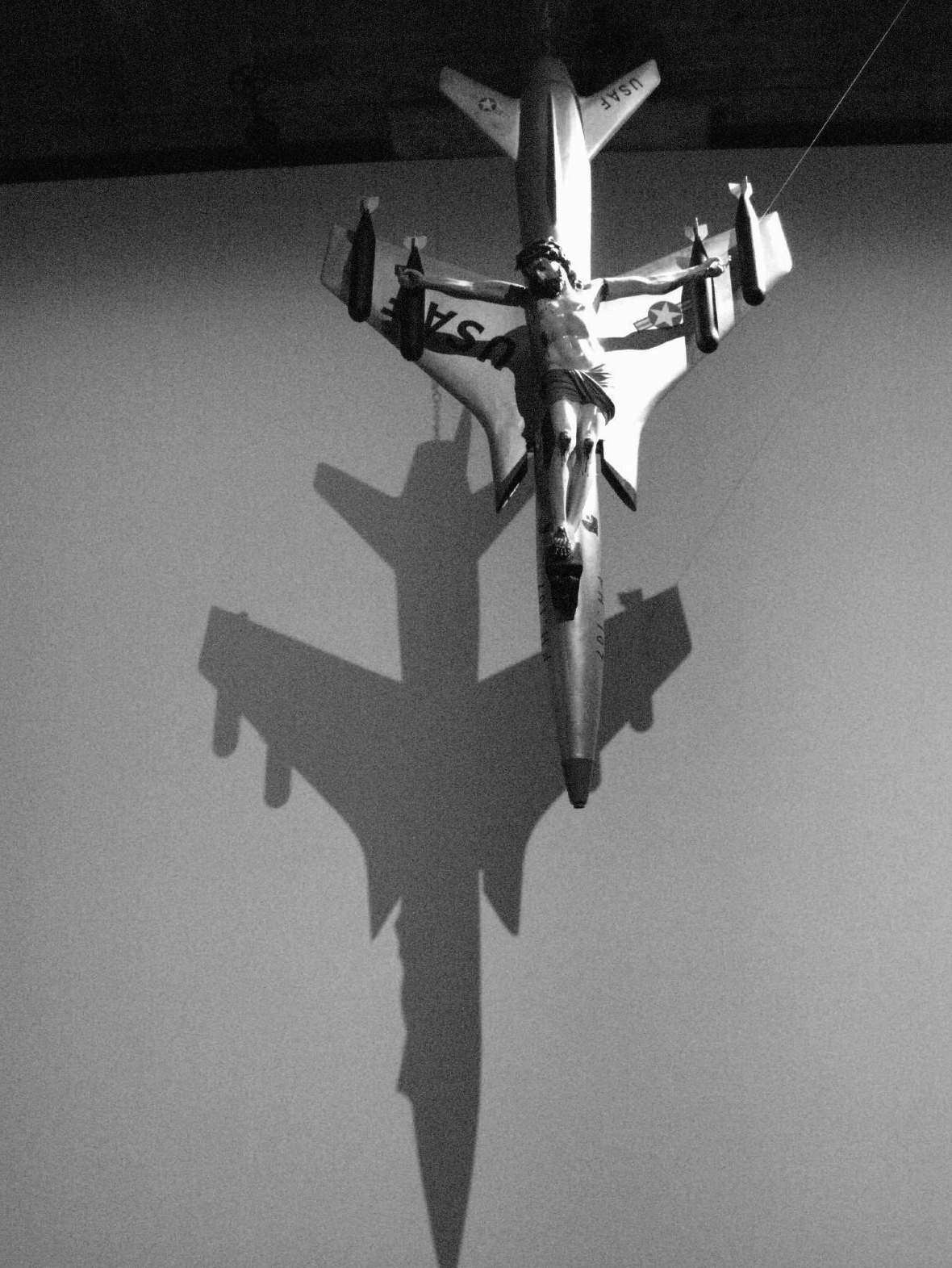

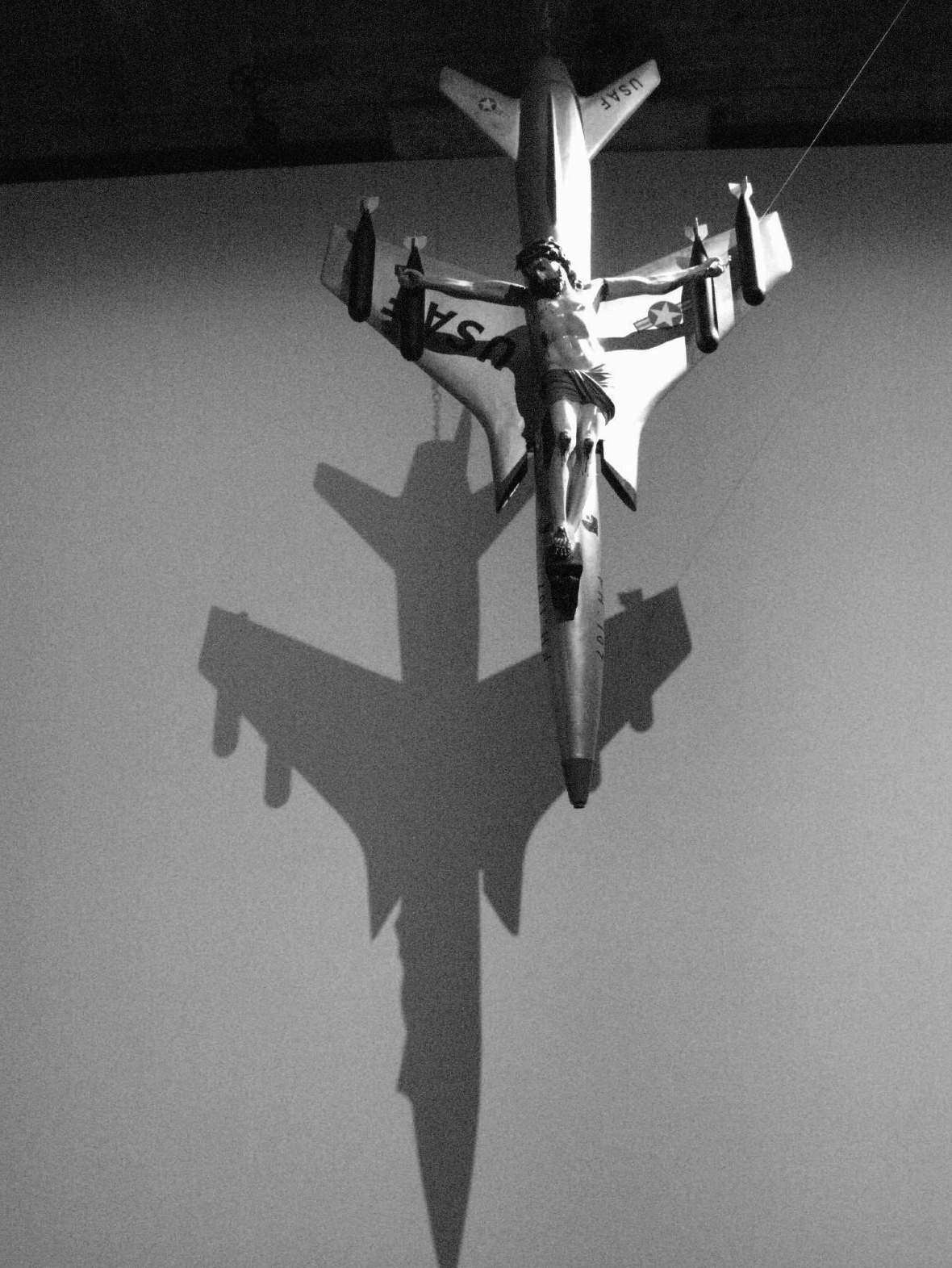

Figure 1_ Western and Christian civilization, Leon Ferrari, 1965 (MALBA collection, exhibited at the 52nd Venice International Art Biennale). Source: Fluvio Spada (Wikimedia Commons, 2007)

Fernando Luiz Lara, Fernando Luis Martínez Nespral and Íngrid Quintana-Guerrero (FLL, FLMN, IQG): Thank you for accepting our invitation for this interview. We have been following your work for some time, and we have no doubt that architects have a lot to learn from art's history and criticism, especially regarding decolonization and overcoming the canon. Our call for this special issue of Dearq is greatly inspired by the exhibition Verboamérica (Museo de Arte Latinoamericano de Buenos Aires [Malba], 2016) and how you, curators, shuffled a collection once exhibited under European concepts, such as impressionism, cubism, the abstractionism, and optical art. Based on a careful reading of Latin American history and geography, you and Agustín Pérez Rubio proposed the following clusters to reorganize the collection: In the Beginning; Maps, Geopolitics, and Power; City, Modernity, and Abstraction; Lettered City, Violent City, Imagined City; Work, Crowd, and Resistance; The Country and The Outskirts; Bodies, Affects, and Emancipation; and Indigenous America, Black America. Can you tell us about the process leading to the establishment of such clusters? Which aspects are derived from the collection and which from its academic production? Were there any works that were difficult to fit into any of these categories?

Andrea Giunta (AG): The virtue of curatorial processes is that they function as a space without conditioning, where one can put into play all the instruments acquired and investigate new ones, to the extent that the works propose them (or one finds them from one's perspective, both informed and subjective). That is precisely what happened to me. If you read my texts of Verboamérica, you will see ideas that I began to nurture in 2012 with the conference Adiós a la periferia (Farewell to the Periphery) that I gave at the Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía. I followed this with the 2014 book-essay ¿Cuándo empieza el arte contemporáneo? (When does contemporary art begin?) and then Verboamérica. The fundamental idea of placing ourselves in the periphery (something that was productively assumed by the cultural and literary criticism of the 1980s) erased the space for innovation, avant-garde, or originality, from which Latin American artists worked. They did not want to be the periphery, they wanted to be the center. Since the 1960s, this has been a strong drive. Even when I may disagree with that desire to shine in the center, the truth is that it existed and must be understood. Otherwise, visual poetics dissolve in the central ones, becoming dull, second-rate copies—something that clearly reflects the curatorial and art markets. Let's not forget that when we cured Verboamérica, with Cecilia Fajardo Hill, we had already been working for six years at Radical Women. Latin American Art, 1960-1985. Therefore, the Malba exhibition was also informed by what we learned in the previous exhibition. We would not have seen in such a porous, diverse, and even consistent way the nucleus of bodies, affections, and emancipation without the other process. The relationship between emancipation and language and the investigation of social and individual affections was very clear to me because I was working on the other exhibition.

Regarding the work process, I must clarify that we did not start with the concepts and looked for the works. We began with the seven hundred pieces that the collection had at that time, printed in color onto paper and with each of their technical sheets. We spent many days with that stack, revising them slowly and discussing each piece. Perhaps those were the most beautiful days of my professional life; passionate and informed. We argued for hours. Many works were left out because one of us was not interested in them, so we had to compromise. The concepts emerged from that intense work. Of course, concepts were informed by readings. From the Lettered City by Ángel Rama to indigenismo, which I explored before while teaching Peruvian modernity, or the affirmation of a black America, which I took from Rosana Paulino. The Country and The Outskirts was inspired by Raymond Williams and Work, Crowd, and Resistance by texts I wrote on the representation of the mass and the multitude, based on the wonderful grammar of the masses described by Elías Canetti (Masa y poder, 1964). Maps, Geopolitics, and Power sparked from postcolonial perspectives.

Figure 2_ Verboamérica exhibition hall (Malba). Source: Andrea Giunta.

It was a game between the readings stratified for decades, which reviewed these themes, and the awakening of ideas and connections that the works produced. Multiple and faceted, like chrysalis; each work oppresses among its forms a wealth of experiences and concepts. You rub some of these aspects into the curatorial proposal. Verboamérica was very much worked within the space. The distance between the works and their order indicated the specific temperature of each room. The assembly of an exhibition represents that additional field of knowledge that occurs when the works vibrate in the room. The distance and the contrasts are fundamental for that to occur. You can perceive more clearly that the work is not an object on the wall, but a package of experiences that you can activate in multiple ways. I am interested in exhibitions containing friendly, pleasant transits, and disconcerting contrasts. I am interested in producing emotions, I like them, and I am not afraid of effects because I want the viewer to accompany me and be moved throughout the exhibition.

The emotional moment in Verboamérica was at the beginning, in the large room where Leon Ferrari's nuclear mushroom hung. It is an image that you will never forget. It is an explosion (which was a reference to destruction), but also the beginning, the start when nothing existed, not even art, and forms were organized from ideas, desires, and imaginaries. That room aimed to replicate the idea of the beginning of the world, the language of art, creation, the first or final explosion and the latency of that moment between destruction and the birth of something new. It was for me a pleasant, dazzling room. On each side, we had Abopuru's work and Torres García's constructive pieces. I remember it and it makes me shiver. It was a dream to see those works confronted.

FLL, FLMN, IQG: Verboamérica was open for a few months at the Malba, which shortly after returned to the traditional ways of exhibiting Latin American art. What do you consider Verboamérica legacies to be? Six years after its inauguration, do you see Verboamérica reflected in later research on Latin American modern art? We also imagined that shuffling the narrative affected the commercial value of the pieces exhibited. How did the art market react after Verboamérica?

AG: Yes, that's right. The exhibition was mounted for two years (which is what it had to be) or even more. When Agustín Pérez Rubio left Malba—which I think was in 2018—the chronological montage returned with European styles, orderly, with all the museum highlights. The light went down, and the museum lost vitality, in my opinion. In later exhibitions—I think of Latinoamérica al sur del Sur (South of the South), curated by Gabriela Rangel, or Tercer ojo (Third Eye), the current exhibition, curated by Maria Amalia García, in which I participated on the advisory board together with Gonzalo Aguilar and Octavio Zaya—the montage by problematic nuclei was taken up again. But Verboamérica did something and that montage is still remembered. It worked as a new model or an answer. I gave a lot of lectures about it. Perhaps in Argentina, it was not very much understood. Regarding the market, no, let's not be so optimistic! Verboamérica showed works by authors such TPS, Ana Gallardo, Graciela Gutiérrez Marx, Eduardo Gil, Mónica Mayer, and Magali Lara that had been left out of the canon, and videos by Bony or Marta Minujin that had been sparsely exhibited. We rescued some works, but that did not intervene in the market. I do not really know about the market. I do not follow the prices of the works to eliminate the influence of that variable in my work. I can write about an artist who is highly quoted or another that is not on the market. I think it was shocking that Latin American art could be seen from categories that did not correspond to the history of art, or styles, but to the idea of lived experience, how Latin America felt, traveled, conceptualized, and lived. We were interested in approaching that experience, not from the history of art, but from the images and concepts that are not the styles or jargon of art, which allowed us to order them. That made quite an impact! In Buenos Aires and internationally it felt like a new curatorial project. I presented it at Princeton, MoMA, and the University of Texas at Austin.

FLL, FLMN, IQG: For us, as architecture academics, it is evident that art history is a decade ahead of us regarding the decolonization of references. We follow in your footsteps and frustrations. However, we are aware of the limitations that both old and current models of art history impose on the specificity of architectural studies. What do you think should be the job of the architectural historian today? What mistakes made by art history in the last ten years should architectural history avoid?

AG: I do not know the backwardness or progress in these areas. In art history, we have broadened our specificity by dialoguing with architecture, cinema, literature, philosophy, and cultural studies. I know architectural historians who have produced an equivalent twist. For example, Graciela Silvestri, Adrián Gorelik, and Anahi Ballent in Buenos Aires. I am interested in architectural history that dwells on the concepts of power; that can reveal projects that have been hidden by official architectural history and that are innovative and interesting. I can think of the remarkable story of Eileen Gray and Le Corbusier, narrated very well by Beatriz Colomina, but also articles I have read about Brasilia by Adrian Gorelik, and, of course, Fernando Lara's recent books about decolonizing Latin American architecture, which introduced specific concepts and dialogues with Verboamérica and Contra el canon (Against the Canon).

Figure 3_ Verboamérica exhibition hall (Malba). Source: Andrea Giunta.

FLL, FLMN, IQG: Contra el canon (2020) is a powerful manifesto that takes Feminismo y arte latinoamericano (Feminism and Latin American art) (2018) completely to another level. In your introduction, you cite Beatriz Sarlo (your doctoral thesis supervisor) and Néstor García Canclini (with whom you have collaborated) as the two greatest thinkers of the late twentieth century around the ideas of periphery, hybridization, and decentralization. Back then, the Mercosur treaty was taking shape, but today (in 2023) it already looks old. What are the main differences you recognize between then and now? Specifically, regarding the 2020/21 Mercosur Biennial, how do you articulate new questions for the Southern Cone regarding today and tomorrow?

AG: The concepts introduced then by Beatriz Sarlo and Néstor García Canclini were and continue to be fundamental because Latin American culture can be understood from the concept of a creative periphery, which subverts and mixes the originals to create something completely different from what European culture proposes. It is a hybrid culture, where times are mixed as much as the erudite, the popular, and the massive. Nelly Richard also contributed to the productive conceptualization of margins (of modernity) to reflect about culture in Chile. However, several years have passed and we see that the way in which the museum market works (forming collections) has devalued, in a sense, Latin American art. Their prices have risen, although not at the same level as the international market. Their presence in international collections is greater but not significant if one considers the extraordinary contribution that Latin American art has made and that it is just beginning to be valued.

If we think that slavery is at the base of capitalism and Latin America was the continent par excellence in the development of slavery, it is here where an unprecedented Afro-Latin American continental culture has been produced, which is just beginning to be represented and studied. The same is happening with indigenous cultures. These image processes do not respond to the isms of modern art or the idea of African or primitive art. It is an extraordinarily rich visual culture produced by informed artists who are intervening in the power circuits of art. The idea of a mixed Euro-Latin American modernity does not help us to think about the cultural tsunami that is taking place, which is illustrated by the multiple activities carried out by the Pinacoteca, the São Paulo Museum of Art (MASP), the Museum of Modern Art of Rio de Janeiro, the Afro Museum, and the recent biennials (both Mercosul and São Paulo). A radical change is taking place. Artists such as Rubem Valentim, Rosana Paulino and Sonia Gomes are being represented by one of the most important galleries in the world, Mendes Wood. The Venice Biennale has also taken a turn. Of course, this does not happen without conflict. The suicide of Jaider Esbell—who led a collective exhibition on the Makuxi cosmogonies, with 34 contemporary indigenous artists—can be understood as a symptom. The artist mentioned in an interview that the conversations with the curatorship of the biennial were not easy. Another symptom was the resignation of the curator Sandra Benites to the MASP, after the censorship of the exhibition Retomada—particularly because of the presence of archival footage from the landless movement. The white and patriarchal artistic culture wants dialogue but when it is dosed and controlled. However, for subaltern sectors—which today have the instruments to understand the power that is played in the field of symbolic representations and collecting—there is no longer time for rhetoric and games. They do not want representation without presence.

Figure 4_ Verboamérica exhibition hall (Malba). Source: Andrea Giunta.

FLL, FLMN, IQG: Contra el canon also highlighted that the quintessential canonical MoMA is changing its narrative to include works “from outside” the canon. It seems that such inclusions are not enough and obey what is known in the United States as tokenism. Where should we start hammering, if we intend to tear down the structure created by the canon?

AG: I love the word you have used, hammering, because you can dialogue, seduce, question, or negotiate (a neoliberal concept from the 1980s and 1990s). However, you also must hammer, in the double sense, by repeating the same movement, always saying the same thing in different ways to make it clear and, at some point, even hammer so hard that everything splinters or that the nail finally enters. León Ferrari mentioned that he always repeated the same thing because the world did not change, and he thought that what he said was not understood.

The curatorial world (collecting) and the museums want to change, but in drops and little by little—placing a black educational curator here, another assistant there, or an indigenous curator. It is happening everywhere—at the Tate, at Quai Branly, in the United States, and Brazil—but that does not mean dialogue is simple or effective. It is slow. Therefore, it is time for a call to persist and not to accept that change is in drops, and that a little painting in a room dedicated to adoring Cézanne, Matisse or Picasso is enough. The pandemic accelerated many changes, including the deep questioning and weariness of the colonial and racist structure of the world.

I am not sure what is going to happen. Some forecasts anticipate the radicalization of poverty and hyper-concentrated wealth, but the local and migratory masses do not stop for a forecast. We are on the cusp of a radical time, in which great confrontations will occur. There is awareness (even from the richest sectors) that there are two options: either they find a world in which they survive alone (something they are effectively working on), or they democratize and seriously save the planet. This second option is not going to happen without conflict. Just look at what is happening in the Netherlands with farmers, who occupy all the streets with tractors protesting policies to end polluting production processes; even though there is a strong tendency to solve this matter.

Independently (but not in isolation), museums have their own crises. Anthropology and ethnography museums in Germany, France, and England—among other colonial museums in Europe—can no longer sustain such collections. On the one hand, they cannot sustain them economically. There are vast reserves from centuries of plundering in Africa and Latin America, supported by massive public budgets spent to keep them closed. Emmanuel Macron has done something symptomatic, which was to return stolen pieces. Additionally, the bronzes of Benin are being returned. I do not think that the return movement will stop. On the other hand, contemporary art museums must accommodate art that was never considered seriously, made by Afro-descendants in the United States and by all the inhabitants of the former empires' colonies. The pandemic, George Floyd's murder, and the post-pandemic have created an urgent scenario.

Museums are under observation, fearful because there will be no way to stop the direct questioning of those contemporary exclusion scenarios that donors, collectors, millionaires, and states have mounted for their glory. There is a deep understanding that symbolic violence is still violence and that it justifies the existence of physical violence towards lives that do not matter. Art must subvert its reduced canon because we will finally be able to understand that art is wealth, diversity, and knowledge, not the reduction of a few works predominantly by male, white artists. Museums began with subtle changes, but while the excluded continue to “hammer,” major changes are taking place. We must persist because we are on the edge of an abyss, and what we can do is operate all possible strategies to make effective change happen. It is time!