Recreate What Has Never Been Created. The Double Paradox of Reconstructing the Formworks of the "House in Jean Mermoz" (1956-1961-1992)*

Igor Fracalossi

igor.fracalossi@ead.cl

Pontificia Universidad Católica de Valparaíso, Chile

Oscar Aceves Álvarez

oacevesa@uft.edu

Universidad Finis Terrae, Chile

o.acevesalvarez@uandresbello.edu

Universidad Andrés Bello, Chile

Received: June 15, 2023 | Accepted: January 29, 2024

Thirty years after its demolition, the House in Jean Mermoz (Fabio Cruz Prieto, 1956-1961), a foundational work of the Valparaíso School, regains substance thanks to a design investigation with the aim of recovering the invaluable experience of being on site. However, what was recreated in 2021 was not strictly a replica but rather what was never seen of the house: the formwork system of the concrete structure. In light of the paradox of replacement by Heraclitus and Plato, and Aristotle's causes, two referential cases are analyzed—the Ise Shrine (7th century) and the Barcelona Pavilion (1929). This raises the need for a fifth cause; the contextual one. Finally, the article presents a critical reflection on the case of the recreation of the House in Jean Mermoz within the issue of architectural reconstructions.

Keywords: House in Jean Mermoz, Aristotelian causes, Escuela de Valparaíso, paradox of replacement, reconstruction.

theseus and the craftsmen (or the paradox of replacement)

After navigating the labyrinth of Knossos, slaying the minotaur, and saving Ariadne and the Athenian prisoners from King Minos, Theseus returns triumphantly to Athens. To keep the memory of this feat alive, the people take the ship on which Theseus sailed from Crete as a symbol or relic of the historical event. Over time, the ship inevitably begins to deteriorate: the wood of which it is made rots, dries out, twists, and ultimately breaks. The first fallen planks are replaced by new planks, faithfully made according to the characteristics of the originals. The craftsmen then embark on the careful and slow task of replacing the decaying elements one by one, preserving the materiality and appearance of Theseus' ship. Decades or perhaps centuries later, the ship continues to exist, but it no longer has any original pieces; no wood or iron, no detail or ornament from the ship that carried Theseus across the Sea of Mirtos to Athens. Theseus' ship is now an object whose parts and pieces have been completely replaced within the ship itself through a slow process of conservation.

Generations pass. With them, the significant relationship between the person and the object progressively diminishes. The task of maintaining the ship becomes increasingly difficult: only a few craftsmen are willing to undertake it. Theseus' ship finally collapses, sinks, and fades away forever. However, the story of the ship does not end with its disintegration. What could be an ultimate end becomes a new beginning: the birth of something more permanent than any material. Its loss brings about a disconnect from history and place, but at the same time, it is the source for the creation of myth.1

The myth of Theseus' ship served as inspiration for the philosophers Heraclitus and Plato for their discussions on the paradox of replacement during the peak of Greek cultural flourishing in the 5th century BCE. Heraclitus, on one hand, argued the impossibility of a thing remaining what it is, while Plato defended the perfection of the idea. The paradox raises some unsolvable questions. If all its parts have been replaced, is it still Theseus' ship? If all the original replaced pieces were reassembled, would it be the same ship Theseus traveled on? The questions address the problem of the authenticity of an object. But perhaps it is necessary to take a step back and ask contrarily, does it matter who the original or firstborn is? For the sensory experience of an object or work of architecture, to what extent does knowing whether something is original or not influence the degree of significance that can be attributed to them?

the causes of aristotle

One of the most studied arguments for trying to answer the paradox of replacement is Aristotle's causality framework. The philosopher proposed that to have knowledge of something, it was necessary to understand its why. That is, the causes that allowed it to come into being and gave it reason for being (2003, 72). Aristotle proposed four types of causes, or reasons, for addressing the knowledge of things: (1) the formal cause, or the morphology of something; (2) the material cause, or what something is made of; (3) the efficient cause, or the process by which something is created; and (4) the final cause, or the utility of something (2003, 79-80). While these causes are not exclusive, the ideal scenario for knowing something, from natural phenomena and geographical elements to mass consumer goods, works of art, and even buildings, is to be able to integrally address its four causes.

Contrary to objects or things, architecture does not seem to exhaust its knowledge from an analysis based exclusively on Aristotle's four causes. Being a field concerned with human habitation, architecture becomes more complex, possessing other attributes that, at first glance, do not seem to respond to Aristotle's proposal, with the most obvious being "place". The geographical point where a building is located is unavoidable, to a lesser or greater degree, for its formation, which involves everything from climatic aspects to historical and cultural aspects. Even the type of soil or mere topography of a site is a factor that influences the design of a building. Therefore, if place is not considered to fit into form, materiality, process, or utility of a building, it seems necessary to add it as a fifth cause that contributes to understanding the nature of architectural works. This could be named the contextual cause.

However, why allude to the paradox of replacement and Aristotle's causes when reflecting on architectural works? Like Theseus' ship, many buildings, some extremely paradigmatic for the history of architecture, have undergone alterations in their morphologies, materialities, procedures, functions, and locations. Aristotle's hypothesis seems to constitute, then, a relevant way of approaching the nature of a reconstruction and revealing its meaning with respect to the original. The application of the four causes, plus the proposed contextual cause, to some architectural references could illuminate different scenarios in which reconstruction has been the subject of debate.

two replacements in the history of architecture

Since the late 7th century, the main sanctuary of Naikū in Ise, one of Japan's most important Shinto temples (fig. 1), has been periodically reconstructed every twenty years with new materials (Martínez 2023, 153). Despite neither the wood nor the stone (material causes) being the same, nor the process and labor (efficient cause) being the same as those used before, wood and stone remain the materiality of the temple. Therefore, there is a significant degree of consistency regarding its material cause. Similarly, the techniques used for replacement work largely remain the same, meaning its efficient cause also endures over time. It is for this reason that, reconstruction after reconstruction, the form (formal cause), the use (final cause), and the location (contextual cause) the current 62nd reconstruction maintains with respect to the first, lead the local community to recognize the temple as a single building that is over thirteen hundred years old. The maintenance, replacements, and partial reconstructions that have been carried out, and will continue to be carried out, are part of the essence of the temple. According to this evidence, the ship preserved in Athens persisted in being Theseus' ship until the end since, despite the replacement of parts and procedural changes, it maintained its form and function. Additionally, the fact that the reconstruction is done slowly and progressively on the building itself, as if it were a living being, and that a significant quota of original material is preserved to this day (Martínez 2023,165), implies the impossibility of separating the presumed copy from the original.

Figure 1_ Ise sanctuary, Japan (1953). Photographer: Yoshio Watanabe. Source: Collection Canadian Centre for Architecture, Montréal. https://www.cca.qc.ca/en/search/details/collection/object/756.

A more recent and controversial case is the reconstruction of the German pavilion originally designed by Ludwig Mies van der Rohe for the International Exhibition in Barcelona held in 1929 (fig. 2). Despite standing for a brief period (only a year) it was reconstructed in 1986 by a group of architects led by Ignasi de Solà-Morales (Macken 2009, 338) to commemorate the centenary of Mies van der Rohe's birth. It had become one of the canonical references of modern architecture, even though very few were able to visit it (Macken 2009, 338). It was a rigorous reconstruction, based on the analysis of historical project documents, so that the result would be as similar and faithful to the original as possible. The Aristotelian causes are fulfilled to a similar extent as in the case of the sanctuary in Ise. The materialities are the same, the techniques are appropriate, the form is undeniably identical, and the purpose is very similar: the pavilion continues to be used as an object of visitation and for hosting events and exhibitions. Furthermore, the location remains the same as in 1929. However, Jaque (2015) reveals that the form of the reconstructed pavilion, apparently identical, has a hidden alteration: a basement intended to facilitate the control and maintenance of services and facilities. Would this novelty weaken the formal cause of the original? The current building has something that the original did not. The reconstruction is not rigorously faithful. Perhaps the most relevant condition for the discussion about the problem of architectural reconstructions, however, is the fact that the pavilion in Barcelona, contrary to the sanctuary in Ise, raises the possibility of reviving a building. Therefore, in this case, beyond the moral debate, the comparison between copy and original is direct, as both are autonomous objects distanced in time but occupying the same place, as seen by Macken (2009, 340). In essence, the conditions that allowed each object to exist are different, except for the abstraction of their causes and the effort to reapply them. If Theseus' ship had undergone a process comparable to that of the Mies van der Rohe pavilion, we would not be facing the ship Theseus sailed on, but a very similar one. The current building constructed in Barcelona is not the Barcelona Pavilion.

Figure 2_ The Barcelona Pavilion (2022). Photographer: Mondo79. Source: Flickr, https://www.flickr.com/photos/mondo79/52590317094/ (February 26, 2024)

house in jean mermoz (1956-1961)

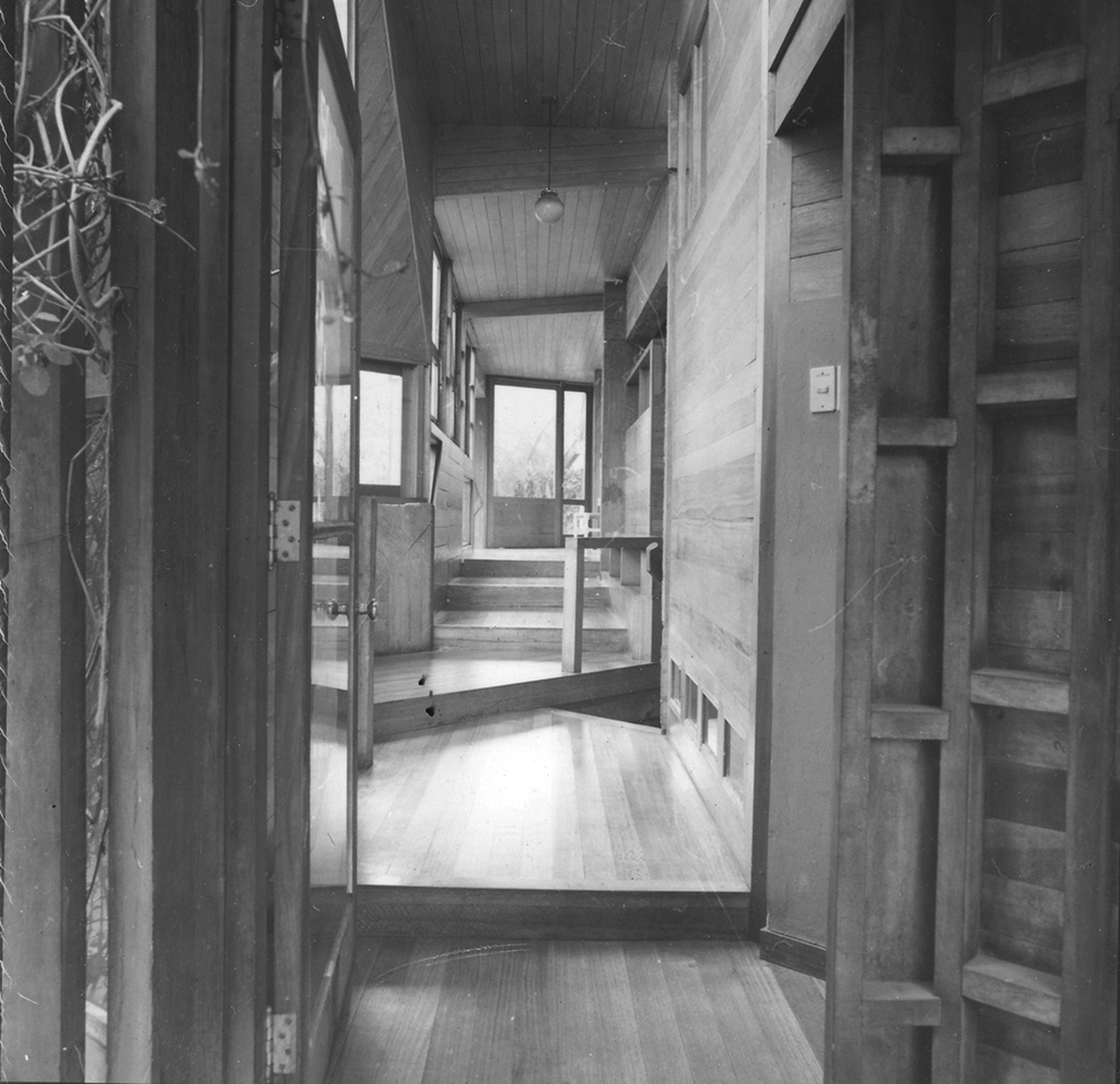

The House in Jean Mermoz was a work by the architect Fabio Cruz Prieto, designed and built between 1956 and 1961 on the street of the same name in the El Golf neighborhood of Santiago de Chile (figs. 3, 4, and 5). It was the first work constructed by the renowned Institute of Architecture of the Pontifical Catholic University of Valparaíso, founded in 1952 by Alberto Cruz, which gave rise to what historiography named as the Escuela de Valparaíso (Pérez Oyarzun 1993; Pérez de Arce and Pérez Oyarzun 2003). This was the first real occasion of conceptual application and formal experimentation in the history of the institute. With it emerged architectural foundations that remain relevant in the training of architects in that institution and distinguish it from others. Among these foundations is the sense of an open work, which determines a way of projecting in conclusive parts that make the building come to life and gradually begin to govern the design and construction process. This notion implies the nonexistence of a total project that visualizes an entire building, which requires trust in the process. Each stage of construction, from earth movements to frames and windows, is designed as an autonomous work, without any definition of the subsequent stage. Therefore, the rhythm of the formation of the work is more of consecutive and evolutionary cycles of lifting-design-construction, in which the previous step determines some conditions for the next one, while undergoing transformations. It is a way of designing in and with the work, without superficial improvisations, but rather from the sensory experience of construction, together with its forms and materials, in the same place.

Figure 3_ Concrete structure of the House in Jean Mermoz under construction (1959). Source: Archivo Histórico José Vial Armstrong, Pontificia Universidad Católica de Valparaíso. Digital composition: Igor Fracalossi.

Figure 4_ Aerial view of the House in Jean Mermoz under construction (1960). Source: Archivo Histórico José Vial Armstrong, Pontificia Universidad Católica de Valparaíso.

Figure 5_ Access gallery to the House in Jean Mermoz (1961). Source: Archivo Histórico José Vial Armstrong, Pontificia Universidad Católica de Valparaíso.

After thirty years of existence, the House in Jean Mermoz was demolished in 1992. The eastern sector of Santiago de Chile, which in the mid-20th century was the city's periphery, consisting of a residential area of isolated houses, experienced urban expansion with a redefinition of uses from the 1980s. Real estate pressure, fueled by the increase in land value, made the sale of land in that sector to large real estate companies unavoidable. The houses were demolished, and business and commercial towers were built in their place.

But with loss comes the possibility of myth. Like Theseus' ship, the House in Jean Mermoz had a complete life cycle. Furthermore, like the pavilion in Barcelona, the house continues to be a representative work of architectural thought for the Valparaíso School and a paradigm of Chilean experimental architecture.2 But why, and for what purpose, reconstruct them? What would happen if they proposed reconstructing Theseus' ship? Would the myth, its presence in history, and its significance be enhanced or diluted? It is not irrelevant to think that the reconstruction of Mies' pavilion was undertaken for reasons similar those of the demolition of the House in Jean Mermoz. That is, of an economic nature, and without any relation to architecture. If so, the reconstruction of the pavilion is no different from the construction of a theme park since their purposes are coincidental: to attract a consuming public within the framework of tourist agendas. The reconstructed pavilion becomes another case of seduction used by the society of the spectacle (Leich 2001, 121-144).

The recreation of the House in Jean Mermoz seems to pose an opposite line to that of the pavilion recreated by Solà-Morales. Its scope is architectural research, therefore its purpose approaches knowledge and moves away from entertainment. However, proposing its reconstruction poses some difficulties. In light of the previous references and Aristotle's causes, reconstructing the House in Jean Mermoz would have aspects in common with both the pavilion and the sanctuary of Ise. Its formal cause, as in all cases, would be the most feasible to recover, while its material cause only to a certain degree: the type of material could be preserved, but the actual pieces and materials, could not. In turn, its efficient cause would resemble the case of the pavilion: it would only be possible to rescue it as a simulation based on a hypothesis about what the construction process had been according to existing historical evidence. However, unlike the previous cases, recovering its final cause (its domestic use as a residence) would imply a new work of architecture in all its complexity, which within the framework of academic research would not be feasible. On the other hand, the proposed contextual cause could not be guaranteed, since it would require the demolition of the current business tower that exists in the original location of the house.

Despite the practical difficulties and conceptual paradoxes, the architectural significance and power of the House in Jean Mermoz, or rather the myth of this non-existent work and what this work would represent as a source of inspiration, learning, and even pride, seem to build the necessity for some part of this work to exist again. Taking up the case of Theseus' ship, its comparison with architecture is not exact: the latter deals with inhabiting and, therefore, with a permanent experience in a specific place. The ship, on the other hand, is a useful object, whose experience occurs within the limited timeframe of its journey, and whose habitability is secondary in relation to its operation. Reconstructing a work of architecture will always enable the sensory experience of its forms, spaces, and materials, inevitably accounting for inhabiting. In the field of architecture as a practical profession mere knowledge of a work is not enough, nor is abstracting the understanding of its reasons or causes; the experience of being in it is essential. Therefore, a pertinent reconstruction should respond to a real architectural experience, not just a scenographic one.

Now, for the recreation of a work from the past to have any value and relevance to the discipline, what must be reconstructed? The whole, like the facsimile of the Mies van der Rohe pavilion in Barcelona, or a part, a fragment, a piece, a detail? What should be reconstructed and what should not be? What can be rescued from the lessons of the sanctuary of Ise? And what should not be replicated from the Barcelona Pavilion?

recreating the never created

The recreation of the House in Jean Mermoz, carried out in 2021, exemplifies another aspect of the paradox of replacement in the case of architecture. A partial recreation of the work was proposed sixty years after its construction. The aim was to recreate something that could never be seen in it, an unavoidable component without which the work could not have existed yet, is the work itself: the system of wooden formwork used for the construction of the reinforced concrete structure. In this way, it would be possible to bring forth the necessary material for concrete to exist: wood. This reveals the other side of things, their reverse, and presents it as a work in itself. Here lies the first paradox of this recreation: formwork is never built in a single stage, so it could never be seen in its entirety.

The House in Jean Mermoz housed three floors: the semi-sunken lower floor, defined by a concrete slab, originally one meter and sixty centimeters below street level; the main floor, defined by the first structural level of pillars, beams, and slabs, one meter above street level; and the third floor, above the second slab, at three meters and sixty centimeters (Fracalossi, 2018). The recreation initially included the set of formworks consisting of pillars, beams, and slabs, as well as retaining walls, from the two structural levels of the house. However, due to the rise in the cost of wood caused by the pandemic, the reconstruction of the second level became unfeasible. What could have just been a loss brought with it an unexpected gift: the possibility of recreating the iron reinforcements of pillars and beams. With them, the recreation would simultaneously bring forth the two components, the two materials that can never be seen from a reinforced concrete structure, under a complementary contrast (figs. 6, 7, 8 and 9). The endeavor consisted of reconstructing an object from the past without falling into the pastiche of the mere recovery of a lost appearance, rather in the quest of giving life to the work, like with the sanctuary of Ise.

Figure 6_ Recreation of House in Jean Mermoz seen from the boundary wall (2022). Photographer: Cristóbal Palma.

Figure 7_ Aerial view that emphasizes the design of the concrete beams of the first structural level of the House in Jean Mermoz (2022). Photographer: Cristóbal Palma.

Figure 8_ View of the diagonal wall through which the house was accessed (2022). Photographer: Cristóbal Palma.

Figure 9_ Interior view of the recreation work that highlights concrete as light (2022). Photographer: Cristóbal Palma.

Once a building is made, whether the origin of its forms and spatial relationships lies in the material problems of the building or in the geometric problems of the project cannot be asserted. What is the cause of this beam? A geometric relationship or a structural necessity? In architecture, both universes continuously intersect, and the author's voice alone is not sufficient to provide definitive proof. To recreate the House in Jean Mermoz, a return to the experience of the work was proposed, but from an impossible moment of its construction: an instant where all the formworks could be seen, like a wooden building emptied of its substance, whose elements contain air awaiting concrete.

Instead of a literal reconstruction, the case seems to be one of recreation. The project is based on a real projective investigation that had to address design problems. To reconstruct an object that left almost no traces, except in photographs and a few plans, deconstructing its consequence (the concrete) was unavoidable. This required systematizing each of its components and parts, deducing its stages of formation, and finally inferring and designing its positive generator, the formwork, and its hidden component (its efficient cause), the reinforcements. The research and design process of recreating the House in Jean Mermoz revealed that these invisible elements also possessed a degree of beauty. Like the structure itself and other parts of the work, they had formal concerns, not just constructional needs.

After six weeks of prefabrication and layout, the formwork for pillars, beams of the first floor, subdivisions of slab formwork, and reinforcements of pillars and beams of the second floor were erected in seven days (figs. 10, 11, 12 and 13). However, due to the schedule, the recreation work could not be completed. The invented internal structure for the formwork of the diagonal wall remained visible, the triangle and diagonal patterns of the slab subdivisions were emphasized on the ground with their shadows, and there was only time to install one of the modular triangular formworks. Only one change was deliberate: removing the back formwork of the beams to illuminate their interior void, placing value on the concrete, now absent in this work. The recreation succeeds in bringing forth, and allowing for the experience of, something that was also the work but had never been observed and admired. It had never been able to display its beauty as a work with full validity. If in cases like this the concrete structures are the origin of the building, understanding their formwork would mean understanding the origin of the work itself, as an ideal state beyond its materialization (Fracalossi, 2018).

Figure 10_ Chantier for prefabrication of wood and iron elements. In the background, the place of work (2021). Photographer: Osdaly Jaramillo.

Figure 11_ Installation of pillar forms and retaining walls (2021). Photographer: Osdaly Jaramillo.

Figure 12_ Installation of the dividers for installation of the slab forms (2021). Photographer: Osdaly Jaramillo.

Figure 13_ Installation of second level beam reinforcements (2021). Photographer: Osdaly Jaramillo.

poiesis of mimesis

It was impossible for the recreation of House in Jean Mermoz not to surprise with its result. Instead of a robust body of concrete that would show something of what the house undoubtedly was, what was seen was a large-scale geometric art installation made of wood and iron. How can this be the House in Jean Mermoz? To what extent does it recreate it? What experience of the original work is being enabled? Why is this also the House in Jean Mermoz? Once again, Aristotle seems to illuminate this crossroads. According to the Greek philosopher, poetry is the art of imitation of human action (García Yebra 1999, 131). Thus, artistic creation deals with the ephemeral nature of processes, not concrete facts. For Aristotle, to imitate a work would be to set its process in motion again. Here, the recreation of the House in Jean Mermoz seems to bet on that conception: the proposal tried to imitate the original sense of open work. Despite the precision provided by the research and design of the reconstruction, including its execution plans, that was progressively developed during the work, the master builders would focus on the present stage of each step and not worry about the next. Returning to Aristotle to reinforce his idea, the philosopher defended the poet as a composing artist who shapes his imitation, going against the notion of a mere improviser, or one who only imitates (García Yebra 1999, 257). For him, for there to be poetry, there must be composition. Consequently, for there to be composition, there cannot be literality. Appropriately, the recreation of this work by Fabio Cruz proposed the imitation of a process, but not a literal stage of construction, rather one critically composed according to the abstract laws of its project. Under that premise, the order of installation of the formwork components sought to highlight a way of explaining why each element, and the whole, were as they were. The recreation of the House in Jean Mermoz is, in itself, a hypothesis of the House in Jean Mermoz. Paradoxically, the recreation recomposed what could have been the process of forming the house. Here is the double paradox: as a product, what it recreates had never been created, and as a process, what it proposed to imitate had never been able to be carried out.

Unlike the sanctuary of Ise and the Mies pavilion in Barcelona, the recreation of the House in Jean Mermoz was dismantled after only three months of existence. Now, like the original house, it no longer exists. However, the disciplinary relevance that exercises like this open lies in highlighting not only the formal and material aspects of a building, but also the intrinsic relationship between designing, building, and inhabiting. Beyond the audience that could experience the recreation, thanks to addressing the efficient cause of the work, those who have truly been involved in the recreation have been its own designers and builders. They therefore become, "at a certain point," as Nietzsche would say (2013, 15), Fabio Cruz and the builders of the House in Jean Mermoz themselves. Undoubtedly, the discussion remains open. The question is not whether we are facing the ship of Theseus or not, but is directed at the experience of building the ship of Theseus, like Pierre Menard's complex, the author of Don Quixote (Borges 1996). Is it worth the effort? The recreation of the House in Jean Mermoz would lead us to suppose that it is.

bibliography

- Aristóteles. 2003. "Las cuatro causas y la filosofía anterior". In Metafísica. Translated by Tomás Calvo Martínez. Madrid: Gredos.

- Borges, Jorge Luis. 1996. "Pierre Menard, autor del Quijote". In Ficciones. Buenos Aires: Emecé Editores.

- Cruz Prieto, Fabio. 2012. Construcción formal (2003), 2nd ed. Valparaíso: Ediciones e[ad].

- Cruz Prieto, Fabio. 2015. Casa en Jean Mermoz. Carta memoria del año 1960. Valparaíso: Ediciones e[ad].

- Fracalossi, Igor. 2018. Volver a la cercanía. Casa en Jean Mermoz (1956-1961-1992). Doctoral thesis, Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile.

- García Yebra, Valentín, ed. 1999. Poética de Aristóteles. Madrid: Gredos.

- Jaque, Andrés. 2015. "Mies in the basement: The ordinary confronts the exceptional in the Barcelona pavilions". Thresholds (43): 120-278. https://doi.org/10.1162/thld_a_00062

- Leich, Neil. 2001. La an-estética de la arquitectura. Barcelona: Gustavo Gili.

- Macken, Marian. 2009. "Solidifying the shadow: Post Factum documentation and the design process. Architectural Theory Review, 14 (3): 333-343. https://doi.org/10.1080/13264820903341688

- Martínez de Arbulo, Alejandro. 2023. "The ship of Theseus: a misleading paradox? The authenticity of wooden built heritage in Japanese conservation practice". Journal of Architectural Conservation, 29 (2): 151-167. https://doi.org/10.1080/13556207.2022.2160554

- Nietzsche, Friedrich. 2013. El libro del filósofo, 2nd ed. Madrid: Taurus.

- Pérez de Arce, Rodrigo and Fernando Pérez Oyarzun. 2003. Escuela de Valparaíso: Grupo Ciudad Abierta. Santiago de Chile: Contrapunto.

- Pérez Oyarzun, Fernando. 1993. "The Valparaiso School". The Harvard Architecture Review (9): 82-101.