How to Cite: Salazar Valle, Marco. "Undeclared Colonial Types in Modern Ecuadorian Architecture". Dearq no. 36 (2023): 26-36. DOI: https://doi.org/10.18389/dearq36.2023.04

How to Cite: Salazar Valle, Marco. "Undeclared Colonial Types in Modern Ecuadorian Architecture". Dearq no. 36 (2023): 26-36. DOI: https://doi.org/10.18389/dearq36.2023.04

Marco Salazar Valle

Universidad Central del Ecuador (FAU UCE)

Received: June 16, 2022 | Accepted: February 1, 2023

Studying ordinary housing types in Quito for a design studio activity led me to question the limitations of local theoretical accounts of incorporating non-canonical works in the literature. This essay develops this idea and analyzes how housing designs by Sixto Durán Ballén and Diego Ponce Bueno are portrayed in important architectural publications by employing diverse uses of the notion of type, allowing the way coloniality is reproduced in domestic spaces to be obliterated. The essay concludes by positing a speculative decolonial type, focused on communal spaces as the basis for experimentation rather than type as a pre-existing image or prejudiced model.

Keywords: type, decolonial, Quito, housing, informal, canon, domesticity.

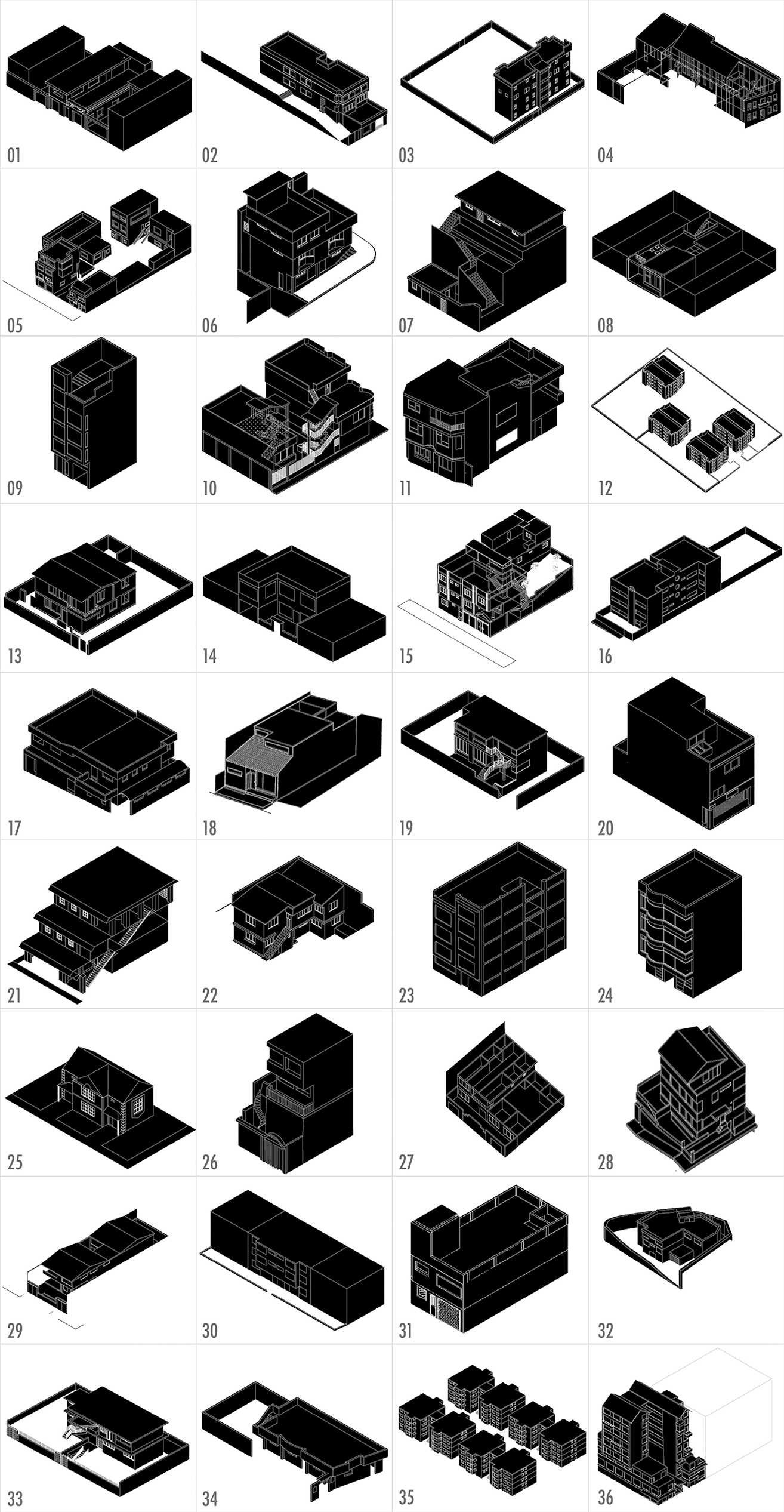

In 2017, I proposed using a methodology for a Design Studio Class for an undergraduate architecture course at Universidad Central del Ecuador that we called Casas Encontradas, or “Found Houses” (Figure 1). The class was based on the ideas of the Argentinian-Chilean architect Enrique Walker (2017) on the ordinary. According to Walker, the Ordinary is related to whatever lies outside the conventional boundaries of the discipline but is incorporated into it by transforming disciplinary tools. In an effort to obtain knowledge without recurring to validation in the modern canon, we sought to ensure our epistemic horizon was focused on informal architecture, as Atelier Bow Wow has done in the case of if its architectural guides to Tokyo (Kaijima, Koruda and Tsukamoto). In a way, by categorizing examples of informal architecture as architectural types, we were unconsciously attempting to engage in what Walter Mignolo defines as decolonial thinking: to be epistemically disobedient by “delinking (epistemically and politically) from the web of imperial knowledge […] from disciplinary management” (2011, 143).

Figure 1_ Casas Encontradas, 2016. Source: the Author.

The exercise relied on our students' observations of interesting attributes of the buildings they would habitually encounter in their daily routines, unencumbered by theoretical concerns. Two students, Mayorga and Santillán (2016) chose a building by the famous Ecuadorian modernist architect Sixto Durán Ballén.1 They showed how the building displayed “informal” aspects (an anomalous gable roof in an otherwise conventional modernist disposition of horizontal slabs) that meant its modernist identity went unrecognized, despite its (albeit relatively little-known) authorship (Figure 2).

Figure 2_ Durán Ballén's Casal Toledo. Source: Katy Santillán and Fernanda Mayorga in Casas Encontradas.

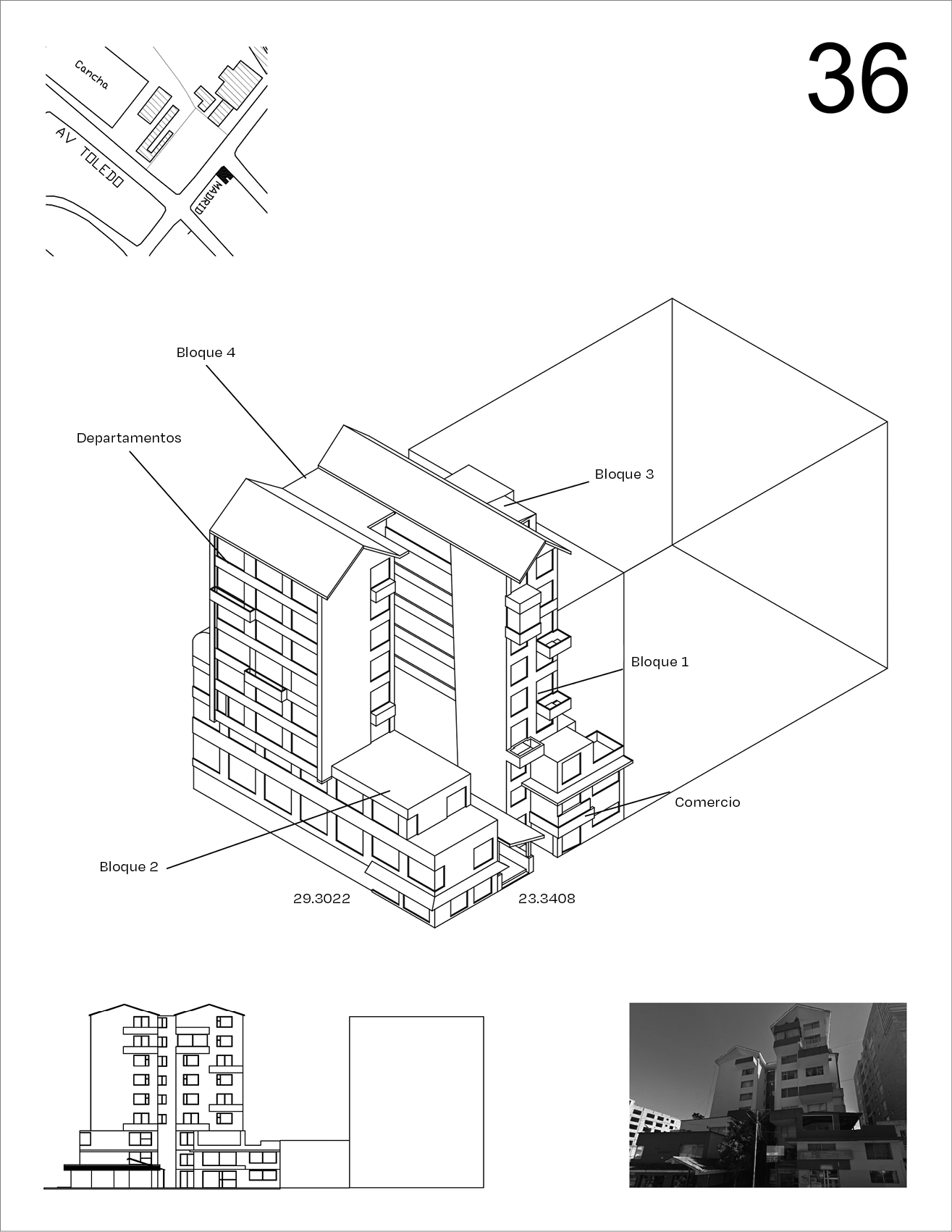

Nevertheless, the book Sixto Durán Ballén: Planificador, Urbanista y Arquitecto Pionero de la Arquitectura en Ecuador, published by Trama (the most prominent architectural publisher in the country) provides a revised vision of his complete works. The building chosen by Mayorga and Santillán, the Casal Madrid, is part of a residential building series whose distinguishing feature is a gable roof (Moya and Peralta 2014, 113). What appears as a deviation from the canon is in fact a calculated marketing gesture intended to distinguish a group of utilitarian residential buildings and create a consistent image.

In Walter Mignolo's words, what is being reinforced here is zero point epistemology, “the pretense of a singular and particular epistemology, geo-historical and bio-graphically located, to be universal” (2011, 81). Zero point epistemology is present geo-historically when casales becomes a rational expression of the European and North American modernist dictum form follows function: “their facades communicate their residential function […]; as do their modulated openings” (Moya and Peralta 2014, 113). Moreover, the term casales had been introduced bio-graphically because of the time the architect spent living in Barcelona. Undoubtedly, the image of Durán Ballén's casales buildings reinforces ideas of colonial influence, including their name, which serves as an allegory of Spanish architecture. These disciplinary discourses validate his building as an authentic modernist experience in spite of its deviations from the canon.

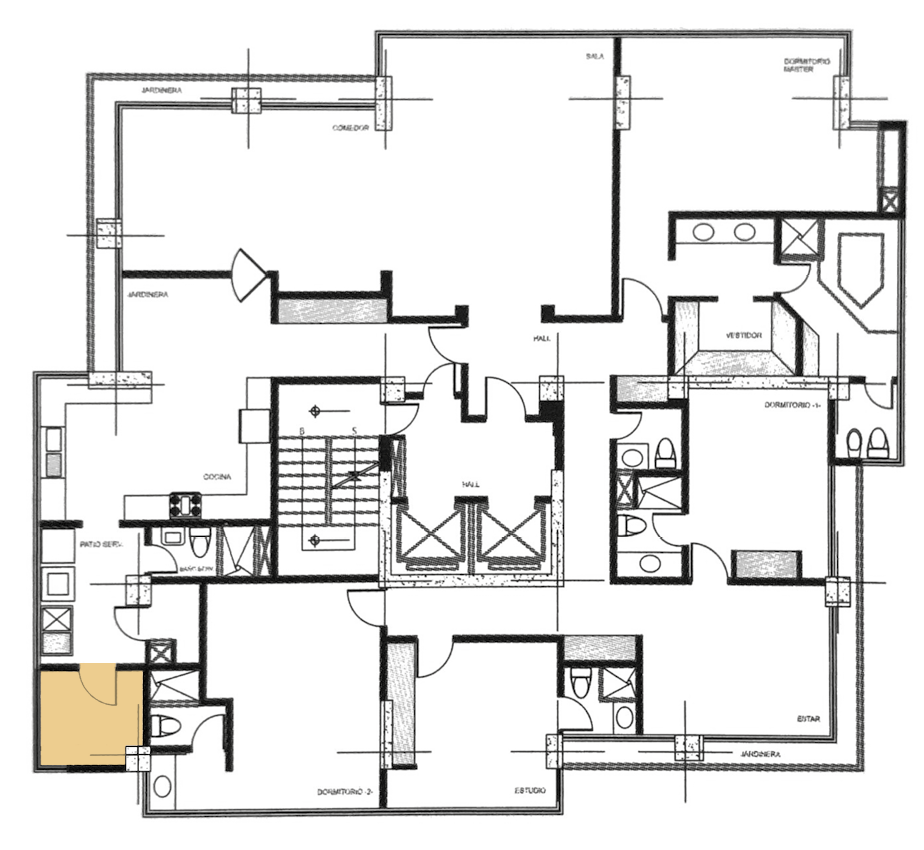

However, a different aspect of colonial legacy is unveiled when the typical floor plan of these projects is inspected, plans that, by their repetition, become typological. In Durán Ballén's casales, there is a bizarre coexistence between domestic modernist functionalism with an (unacknowledged) dark, non-functional, irrational bedroom space always located next to the kitchen: the maid's room, or the space made available for the “live-in maid.”2

Maid's rooms as colonial lag are not unique to modern Ecuadorian architecture. Even in small modern apartments, Brazilian modernism sublated (or preserved) the senzala, the typical slave dwelling of colonial times, in the form of a maid's room squeezed in next to the laundry space (Fantinatti 2018). In Ecuador, domestic life has seen a similar dependence on servants to that shown in Brazil. The huasipungo remained in use after the demise of the Spanish colony and shared features with the senzala: both were detached structures, physically separating servitude from aristocracy, but still incorporating abusive forms of domestic labor. Arguably, the role of huasipungo dwellings was also sublated in the functional layout schemes of modern housing in Quito.

The presence of a maid's room, poorly ventilated and lit, with barely enough space for a bed, is recurrent in the work of the architect Diego Ponce Bueno—who was related to Durán Ballén's Uruguayan partner Gilberto Gatto Sobral (Figure 3 and 4). Diego Ponce Bueno, who studied architecture in Rio de Janeiro, is one of the few architects other than Durán Ballén to whose work Trama has dedicated a comprehensive publication. I focus on the case of Ponce Bueno because the thorough review of his work carried out by local authors makes it possible to trace the typological narratives in his work, despite the fact that he purposely avoided typological consistency in his work, in an attempt to ensure “that type doesn't assert unconditional influence and it remains possible to propose new solutions rather than those we are accustomed to” (Moya 2014, 16). His work does in fact follow a type that resides in the image of domestic life built into all his projects, one that depends on the inheritance of a colonial convention whereby servants live side-by-side with elite families (Kingman 2006, 191).

Figure 3_ Typical Floor Plan of Diego Ponce Bueno's Torres de Almagro Project. Source: Ponce, Maria and Fabiano Cueva. 2014. Diego Ponce Bueno: Arquitectura y Ciudad. Quito: Trama Ediciones. 30.

Figure 4_ Typical Floor Plan of Diego Ponce Bueno's Torres Panoramicas Project. Source: Ponce, Maria and Fabiano Cueva. 2014. Diego Ponce Bueno: Arquitectura y Ciudad. Quito: Trama Ediciones. 184.

Let us consider Antoine-Chrysostome Quatremère de Quincy's concept of type. It is the case that he referred to the notion of a model employed not only in architectural practice but also in religion: type as the manifestation of character or as an image susceptible to reproduction, rather than the synthesis of a group of buildings that share similar features. That is to say, in this first definition, there is an attempt at an a priori rationalization of architectural production, which should commit to a repetition of solutions that denote a particular character. Thus, in the case of Ponce Bueno's domestic designs, architecture is typified (even if this is undeclared) as deploying detrimental spatial features for domestic workers that preserve a colonial character, an image of the superiority of the colonizers: “the inhumanity of Humanitas,3 the irrationality of the rational, the despotic residues of modernity” (Mignolo 2011, 93).

Quatrèmere de Quincy's definition of type dates to the 18th century, at the threshold of the development of architecture as a modern discipline. From that date on, the architectural type would evolve into an abstract entity that permits a utilitarian and intellectual deployment of a rationalized architectural episteme. In other words, it came to represent the ambition of cataloging historical types to create an absolute knowledge of architectural possibilities or the scientific/utilitarian evaluation of functional alternatives (Vidler 1977, 95-115). In any case, types seek a universal determination of what exists or, at the least, what has been included within the confines of the discipline.

This inclusion implies classification. As Walter Mignolo explains, “rational classification meant racial classification. And rational classifications do not derive from 'natural reason,' but from 'human concepts' of natural reason” (2011, 83). Starting in the 18th century with the predecessors of architectural typification, the architecture of the Americas was not denied but rather established as savage and picturesque, thereby ensuring it fit easily into the contemporary notion of the informal. The concept of type elaborated by Quatrèmere de Quincy recognizes the necessity of an original model as the source of all subsequent examples of architecture. The notion of the original model undermines all other non-European possibilities of origin (Vidler 1987, 157).

The definition and use of architectural type as a disciplinary episteme in the 18th century coincided with the quest for European racial superiority, which was justified by recourse to scientific classification. Various cultural productions were thought of as promoters of diverse architectural types, a process Irene Cheng describes in “Structural Racialism in Modern Architectural Theory” (2020, 137-143). However, in his text “A Black Box: Architecture and its Epistemes,” Tom Avermaete discusses typology as a fundamental operative episteme in a kit-of-parts for architectural practice (2021, 71-74). Along with phenomenology, semiotics, and praxeology, Avermaete insists on the 18th century synthesis of architectural types as formal compendia of precedents and a point of departure for architectural design. However, Avermaete also includes typological reasoning as a tool for empirically reading urban morphologies, acknowledging the considerations of Muratori, and later Rossi, about type as a modern episteme.

Avermaete (2021) affirms the inevitable and often unconscious use of epistemes—such as typology—in architectural practice and territorial analysis. It might therefore be implied that the notion of type as a racialized episteme remains unchallenged. Considering that every return to the notion of type regards its enlightened origins—from Muratori through Rossi to Avermaete, it should also be noted that Quatrèmere de Quincy “foreshadowed a trope of Europeans being considered the people capable of progress and historical advancement, while other groups were condemned to historical stagnation” (Cheng 2020, 137).

For the editors at Trama, the work of Ponce Bueno can be inscribed in the canonical discourses of the modern movement. Here, type is used as a conceptual tool to rationalize an architect's production in an apparently coherent schema whose result is to cloud the concreteness of Ponce Bueno's work and his Brazilian training. For example, the review of his work disregards its resemblance to the architecture of São Paulo, as in the case of his own Filantrópica Building, which share similar formal solutions with Rino Levi's FIESP Building. On the contrary, an omnipresent influence of Le Corbusier is redundantly stated by Trama's editors, even if none of his work actually bears any concrete resemblance to any of the Swiss architect's buildings. Le Corbusier is not only credited as a “pure modern” influence that established “the style and discourse that accompanied the rest of Ponce Bueno's professional life” (Peralta 2014, 38), but he is also portrayed in a two-page image that gets more space than any portrait of Ponce Bueno himself in the book Diego Ponce Bueno: arquitectura y ciudad (Ponce and Cueva 2014).

Le Corbusier is more directly mentioned as the inspiration of the general principles underlying Ponce Bueno's work, namely “the fundamental concepts of pilotis, free facade and horizontal windows […]; point support and open floor plans are present in his tall buildings [… as are] roof gardens, which – in contrast to gable roofs – can be put to practical use and lent to surveying the surroundings [of the building]” (Peralta 2014, 38). This generalization of modernism as a set of rules allows Ponce Bueno's work to be accepted as an authorized representative of that canon.

Therefore, including Ponce Bueno's work in a general canon is a typological operation that selects fragments of his buildings in order to fulfil the requirements of a predefined discourse. This notion of type is similar to Quatrèmere de Quincy's first definition of type as image, which is also similar to the archaic notion of typology used by religion in the 16th century to adjust empirical evidence concerning the new world to pre-established biblical tropes (Cañizares-Esguerra 2009, 237-264). Within this notion of typology, empirical reality is ascribed to more common terms that could help understand it at an epistemic distance (for instance in the way the American reality was forced into biblical stories that were then assimilated by Europeans). In this process, empirical reality must be simplified (abstracted) if it is to fit into an alienating discourse.

This simplification by abstraction obliterates alternative epistemic formations that would contradict the zero-point epistemology (Lara 2022). For local representatives of the canon, these general discourses on modernity allow the work of architects like Ponce Bueno and Durán Ballén in Ecuador to be included in the zero point epistemology by obliterating more telling aspects that fall outside its confines. Consistent and reiterative strategies in their designs, such as the maid's room, are always present as an undeclared functional and spatial requirement, but obliterated for the sake of the canon. In other words, what architectural discourse has done is to “purify” architectural practice with modernist discourses by obliterating the darker side of this modernity, which can only be made visible by putting “truth [the universal canon of modern architecture] in parenthesis” (Mignolo 2011, 52).

Fernando Lara and Felipe Hernández have made particularly rigorous attempts to decolonize architectural knowledge. Their texts Decolonizing the Spatial History of the Americas (2021) and Spatial Concepts for Decolonizing the Americas (2022) provide seminal theoretical frameworks, which in this case allow us to locate the use of type as an episteme for perpetuating colonial validation in Ecuadorian architectural discourses. Concerning the role of architectural knowledge in ensuring the persistence of the colonial, they affirm that “the fields of architectural history and theory focus on the construction and maintenance of a canon, which provides the basis for architectural judgment: what is architecture and what is not” (Lara and Hernández 2022, 2). Hence, attempts to decolonize the notion of type represent an effort to liberate this architectural episteme so that it may leave behind its canonical pretensions and accept the local built environment empirically, in all its formal and cultural complexities.

Walter Mignolo defines the decolonial option as “the analytic of the construction, transformation, and sustenance of racism and patriarchy that created the conditions to build and control a structure of knowledge, either grounded on the word of God or the word of Reason and Truth” (2011, xv). In the case of Ecuadorian modernism, as shown by the examples of Sixto Durán Ballén and Diego Ponce Bueno, we may conclude that type is an episteme for fitting architectural production into a pre-established image, which resembles the religious aura of colonialism (its canon being general discourses on the modern movement). The colonial implications of typological surveys then rely on trying to mimic a European notion of classification, which Mignolo opposes by proposing a relocation of the locus of thinking, by “being where one thinks [...] recognizing and confronting both imperial categorizations of being and universal principles of knowing; it means engaging in epistemic disobedience, in independent thoughts, in decolonial thinking” (2011, 96-97). Nevertheless, a decolonial option does not in this case imply invalidating the notion of type, but understanding that it can be “a model of what to do, and not of what to think” (108).

Type permits classification under the restrictive confines of a model. This definition presupposes the existence of a priori transcendental motifs or images, which Quatrèmere de Quincy, based on monumental references, called “character” (Vidler 1987, 154). Type, then, becomes not only a classification tool but also the means for validating architectural production as transcendental enough to be considered architecture, and innovative enough not to be a mere replica. If we consider how traditional architectural studios work, is it not precisely this pretension of validation under predefined models that allows the critic-professor to inscribe their students' work within his matrix of architectural models? Is this not how the architectural canonical episteme is repeated in architectural studios? If we take what Anthony Vidler and later Tom Avermaete affirm concerning the evolution of the notion of type in academic architecture as the fundamental knowledge of the discipline, what happens when we put this truth in parenthesis to avoid repeating a notion of universality established in Europe in the 18th century?

Returning to the experience of the Casas Encontradas exercise at Universidad Central mentioned at the beginning of this paper, “disobeying” the canonical notion of type implied putting the a priori validation it presupposes in parenthesis. This in turn meant relying on the subjective approach of architectural students and valuing the “ingenuity” of observations outside the matrix of canonical models. It also implied demystifying the informal, which the architectural episteme has left out by generalizing it as a type of building practice not produced under disciplinary canons. In understanding the fine grains of informality, we might have contributed to building another episteme, which would require different approaches to classify and validate what has been produced outside the modern canon. By leaving out the presupposition of a monumental historical image in the notion of type, a decolonial option sets out from the evidence in order to find what is shared by a particular group of buildings.

As has been shown, even in examples that are considered canonical, if we exclude discourses that typify them as officially modern, we are left with similar informal examples that are comparable to ordinary ones. Nevertheless, once we obliterate the discourses that prioritize some authors and some productions over others (formal over informal), we can compare them for what they are in concrete terms, establishing more pertinent categories than “form follows function” or “the liberation of the plan.” For example, an examination of the ways different housing complexes manage their communal spaces can reveal new categories that validate what has been produced outside the canon.

An examination of Diego Ponce Bueno's Conjunto Torres Almagro shows that this housing project created a rule of maintaining a maid's room as a common category for all apartments, regardless of their size. In a way, the existence of the maid's room is part of a strategy to build an image of an elitist construction in line with a colonial tradition, which also includes the provision of a covered pool and a heliport as communal areas that are hardly ever used. In contrast, during the preparation of Casas Encontradas, Adriana Medina studied a low-rise housing complex in Guamaní that forced its inhabitants to share a common area establishing a “communal relation” (2006, 10). These houses “share a common laundry area and a patio, creating a shared space for their inhabitants, either to satisfy the need for cleanliness or to provide play areas for the children who live there” (10).

The principal difference between Ponce Bueno's project and Medina's findings is constituted not merely by a design feature but, more importantly, by the social iterations they promote—which are also designed and not accidental. Despite their typological differences, the former being an apartment block and the latter a low-rise communal housing, it is possible to compare them by recalling the rational episteme of type as the formal and structural identity of the buildings. While Ponce Bueno's design separates communal spaces vertically and distributes laundry spaces within service areas in each apartment, the ordinary houses in Guamaní are organized around the laundry room and the patio as a common space (Figure 5). Under functionalist eyes, or elitist modern canons, a communal area where recreational spaces and service activities coexist would be a mistake.

Figure 5_ Casa Comunal. Source: Adriana Medina in Casas Encontradas.

The recognition of students' observations as decolonial architectural knowledge needs to be contrasted with canonical examples such as the architecture of Ponce Bueno since, as Mignolo argues, “decolonizing knowledge is not rejecting Western epistemic contributions to the world. On the contrary, it implies appropriating its contributions in order to then de-chain from their imperial designs” (2011, 82). This comparison coincides with the concepts used by Mignolo of “Humanitas” versus “Anthropos” as epistemic rather than ontological opposites that are codependent of a notion of modernity that builds on colonial difference: Humanitas being the civilizational project that separates and triumphs over other forms of humanity, or Anthropos (96 and 97). As Mignolo puts it, “Humanitas” and “modernity” [..] are concepts allowing those who manage categories of thought and knowledge production to use that managerial authority to assert themselves by disqualifying those [Anthropos, simultaneously barbarians and traditional] who are classified as deficient, rationally and ontologically” (82).

Therefore, what is relegated to the status of informal in architecture could be directly related to the notion of Anthropos, not because of its ontological nature but because someone else categorizes it as such. Architecture is categorized when someone differentiates between the formal and the informal, but also when its inhabitants are discriminated against for belonging either to Humanitas or to Anthropos. The modern canonical discourse that validates Durán Ballén and Ponce Bueno's work hides and relegates the place of the Anthropos, either as a “maid's room” or as “informal” architecture. The maid's room parallels Mignolo's “darker side of modernity” because, “hidden behind modernity [is] the agenda of coloniality; that coloniality [is] constitutive of modernity; that coloniality [is] the secret shame of the family, kept in the attic, out of the view of friends and family” (2011, xxi).

The communal space in Medina's typological observation is an epistemic contribution to the architectural field from the perspective of Anthropos, as a “geo- and body-politics of knowledge” (Mignolo 2011, 82). It is not accidental that her observations conclude by valuing the social inputs represented by communal space. This conclusion may be reached by putting the canonical truth of the notion of type in parenthesis, a procedure that would ensure the notion of type “could coexist in a pluriversal world, a world in which truth and objectivity in parenthesis are sovereign. For there is no entity that can be represented by the common, the common good, or the communal” (52).

The outcomes of this design studio experience are an example of this process of decolonizing architectural types. The research on ordinary typologies in Quito showed that communal spaces are always present but only sometimes share a common spatial configuration: sometimes as a patio and sometimes as a terrace or as stairways. It also showed the intrinsic relation between privacy and commercial activities as a promoter of communal spaces. Students were asked to synthesize these features to design a collective housing project, being required, that is, to create types from these dispersed observations. Santillán's design for collective housing (Figure 6) deploys an array of terraces, patios, and stairways that are purposely made abundant to create situations similar to those found in informal dwellings. Nevertheless, they are typologically different from existing examples of collective housing in Quito, though they might share features with Moshe Safdie's Habitat 67. In this case, a typological investigation is useful less to provide a standard for repetition or evidence of tradition to be embraced: it is more a starting point for experimentation.

Figure 6. Student's axonometric of collective housing project in Quito. Source: Katy Santillán.

Despite the similarity with Safdie's work and the possible influence this exerted, to compare Katy Santillán's experimental design with this iconic example of architecture would be detrimental to the decolonizing agenda. A comparison is only feasible if truth about architectural types, (i.e. their canonical horizon) is put in parenthesis. This being the case, Shafdie, or Habitat 67—or any other discursive image of canonical examples of modern architecture—would no longer be a prejudiced model to evaluate against any project that shares its typological features; it would no longer be the truth. In other words, architectural design does not need referents but empirical examples that operate simultaneously.

If the notion of type allows an a posteriori validation of selected architects, this is only achieved by reducing buildings to images: architectural production forced into a discursive matrix based on prejudices. When putting this notion of type-as-image in parenthesis, the reality of the built environment becomes a fertile ground for learning from real buildings, rather than an abstract contextual background from which architectural projects emerge. These empirical lessons could be deployed by engaging in a decolonized episteme of type, but not, this time, in an uncritical stereotyped fashion. Can we learn from examples of non-canonical architecture, by engaging in the canon and working both for and against it?

1 Among other significant positions, Sixto Durán Ballén was founding professor at Facultad de Arquitectura y Urbanismo at Universidad Central del Ecuador, Mayor of Quito and President of Ecuador.

2 Maids are usually young women of indigenous origins and are frequently employed in Quito's middle and upper class homes.

3 “Humanitas” is the term used by Mignolo to identify the civilizational project of Western modernity that puts all other non-western populations as uncivilized.