How should man’s conscience —his artistic conscience above all— react to this world that is blurred amidst the echo of battles?

Héctor P. Agosti (1945)

Beginning in 1934, Joaquín Torres García promoted a constructive and universal art that harboured utopian ideals. Following the appearance of Arturo magazine in 1944, some young Rioplatense artists gave a further utopian dimension to the constructive-based modern art they proposed. The expansion of fascism, the Spanish Civil War and World War II were interwoven between these two points in time, and were events that triggered a historical trauma that differentially marked the imagination of the generations that experienced that period.

Although the newspapers of the 1940s reported on human losses, and on military action, tanks and airplanes, their pages also revealed that this world war was one of science, research, inventions, engineering works, and technology. Although the newspapers were immersed in an absurd tragedy that contradicted the developments gained by reason, far away from the battlefields, science remained in a privileged position and the dissemination of some scientific advances found a substrate bordering on science fiction1. As expressed by the literary critic Max Daireaux (1940) in one of those newspapers, for older artists, the war represented a rupture in their creative project, after which “the old forms could almost never be resumed or adapted to new forms”; he added that those of his generation knew that the war shunned everything that had preceded it as dead and that “a new spirit, born of the war, should start from scratch”.2

It is understandable, then, that the youngest witnesses of these historical events were those who were in the best position to devise an alternative response. For them, the explosion of the atomic bomb in Hiroshima and Nagasaki went beyond a catastrophe that struck the human race, as the disintegration of the atom was also the event that inaugurated the moment in which they could assume their role as protagonists of change and adopt an active role in the re-foundation of daily relations among humans. It is thus on this basis that we intend to approach Torres García’s constructive proposal and the avant-garde Rioplatense Concrete Art project. To this end, we review their programs and, according to their postulates, analyze both the utopian horizon they outlined and the practices they proposed to pursue it.

Constructive and Universal: Integration of the Torres-García Program in Montevideo

My dear friend, Torres:

I believe that America still has idealistic men […] that is why I do not doubt that American youth will find in you a true propellant and that they will be able to follow and understand you.

Gustavo Cochet3

Upon his arrival at the port of Montevideo on April 30, 1934, Torres Garcia4 was convinced that universal Constructive Art was the way forward for America; however, his ideas were met with a great deal of resistance. It was a collective, anonymous, and monumental art, made of pure geometry, rhythm, and structure, which included the symbol as a synthesis of idea and form. An art that aspired to recover the space lost in the process of autonomization and, consequently, was proposed as a form of integration with the order of the universe in which aesthetic production would be part of collective practices.

With a view to introducing his ideas in that context, and given the warm welcome he received from the Montevidean intelligentsia, in May, he summoned all the artists interested in promoting modern art to form the Asociación de Artistas del Uruguay5. Conceived as a strategy of integration, it was adhered to by artists such as Carmelo de Arzadun, Héctor Ragni or his son-in-law Eduardo Yepes —who would continue to support him— and others who, due to their aesthetic orientation or political intentions —Carlos Prevosti, Luis Mazzey, Zoma Baitler, Norberto Berdía, and Gilberto Bellini— would resist. He opted for a policy of alliances similar to that which he had implemented together with Theo Van Doesburg and Michel Seuphor, when he founded the Cercle et Carré group to unite those who opposed surrealism6. However, Torres also knew that internal differences destabilize groupings, as he himself had, on the Parisian scene, had to deal with the discrepancies that, from the outset, had manifested between his ideas and the more radicalised positions7.

In July, Torres García presented his first exhibition at the Young Men’s Christian Association, introduced by a brief text of his own in which he explained the following:

These works are conceived to be created on a large scale - monumental works (without prejudice to the fact that the current works are already definitive realizations), works that should be executed in stone, glass, mosaic, pottery, fresco, fabric, etc. That is to say, the noble procedures of another time. It is the idea of an art that in another period could have been collective work and that today will have to be individual.8

In August, the Asociación de Artistas del Uruguay began working in the premises of Uruguay 1037 —a space it called Estudio 1037—, where the works of some local artists9 were exhibited together with those of European avant-garde artists, such as Jean Hélion, Pere Daura, Otto van Rees, and the Mexican sculptor Germán Cueto. However, Torres’ lessons and lectures soon sparked the initial controversies10. He understood then that, in this new scenario, he would have to face the resistance of the critics and the public, and in 1935 Estudio 1037 was replaced by the Asociación de Arte Constructivo (aac). With this new group, the master reoriented his strategy and gave it a clear direction by inverting the map of South America(img. 1), an image that graphed the sentence “our north is the south”, to point out the need to concentrate efforts on his own and abandon dependence on Europe, as stated in his Lesson 30 “The School of the South”. Referring to the will of integration in man’s vital experience, in Lesson 33, he also explained that:

every art that has a universal foundation […] must be a great complete movement, and therefore affect, not only the other arts, but more directly the applications to various purposes (as it always has), mural painting, glass, mosaic, weaving, ceramics, wood carving, furniture. That is, all kinds of objects, whether useful or not (and you need to pay attention here), leaving the so-called higher arts totally abolished.11

This lecture, given in February 1935 at the Uruguayan Theosophical Society, was attended by Carmelo Arden Quin12, who from that moment on was a key player in the link between the torresgarciano environment and the avant-garde of concrete art that was born around the magazine Arturo.

In July of that year, Torres García also signed the preliminary note to the book Estructura, dedicated to Piet Mondrian, in which he laid down the rules governing his art. In May 1936, he promoted Círculo y Cuadrado, a magazine published by the Asociación de Arte Constructivo, as the “second period” of Cercle et Carré(img. 2) and (img. 3). This publication disseminated the guidelines of Constructive Art, without neglecting the knowledge of modern European art and the search for pre-Columbian roots. In his exchanges, Torres shared his network of contacts —European artists— with the Montevidean scene: Hélion, Piet Mondrian, Umberto Boccioni, Amedée Ozenfant, Van Doesburg, Georges Vantongerloo, Jean Gorin, Gino Severini, and Angel Ferrant, because the magazine published fragments of letters or the news it received. He also shared the international magazines; including, Italy’s Il Milione, England’s Axis; Índice and Gaceta de Arte published in Tenerife; the Parisian These, Antithese; Synthese from Lucerne; the Swiss Kunsthaus; the French Cahiers d’art, Abstraction Creation, L’Élan Universaliste, Sagesse, and Volonté; along with a few Latin American ones from Ecuador, Colombia, Peru, Costa Rica, Cuba, Mexico, Chile, and Argentina13. As a result of his friendship with Vicente Huidobro, Torres established his presence in Chilean magazines and connected with the young painters, sculptors, architects, and writers in Grupo 1933 and the Decembrista group14, to whom he dedicated one of his exhibitions.

The aac was finally constituted in May 1937, on the basis of respect for personal ideas and with the aim of working within the order, the measure, the frontal law and the pure concept of form, in which the Universal Man should dominate over the individual. The aac undertook a program of study that involved archaeological research and Indo-American expressions. Meanwhile, the master published his theories in La tradición del hombre abstracto (1938), Metafísica de la prehistoria indoamericana (1939), and La ciudad sin nombre (1941).

The works of the aac traveled to Paris in 1936 to be included in the “Salon de Surindépendants” and, in May 1938, the same consignment was exhibited at Amigos del Arte in Montevideo. However, while the constructive program reaped recognition abroad, local resistance frustrated the master, to the point that, in December 1938, he wrote in Manifiesto nº 2. Constructivo 100% that he had no objection to admitting that “Constructivism has gone. Nobody thinks about it. Its own propagator is no longer busy insisting on it with his lectures. That annoying thing has finally passed!”15.

Image 4.

Presentation of the exhibited pieces in Salon de Surindépendants in the 5th version of the AAC exhibition

Nevertheless, the group exhibitions continued even though Torres García disappointedly declared that he was returning to painting after dedicating five years to disseminating Constructive Art through his lectures. He added: “it seemed good to me to introduce figuration in my art […] instead of being schematic art, it is already figurative art, but within the rhythm and the frontal law, what I call constructive painting”16. In November 1940, this new rethinking synthesised the accepted defeat together with the announcement of the “bases for constructive painting”, pronounced in the well-known 500ª Conferencia or 500th Conference. Gabriel Peluffo Linari pointed out that the conference marked a turning point in his teaching, allowing him to unify his pictorial experiences in the same framework and, at the same time, to herald it under the appearance of an adaptation to the local reality17.

After this discouraging period, at the end of 1942 and following the success of his solo exhibition at the Galería Müller in Buenos Aires, Torres decided to renew the strategy of introducing Constructive Art by creating a new group: Taller Torres García (ttg). After a five-year interruption (1938-1943), Círculo y Cuadrado published issue 8-9-10, which highlighted the changes that had taken place during that period. The cover announced the local anchorage in the constructive image (man-woman-sun-ship) designed by Torres Garcia, which displaced the logo inherited from the Parisian magazine and recovered the Spanish words Círculo, Cuadrado, and Montevideo. While the master defended the work on painting and Constructive Art and an exhibition of the recently created ttg was widely publicised, an article signed by Ragni explained the ups and downs of the aac —in terms of those who left for lack of conviction in the program and those who could not bear the burden of hostility and mockery of the environment— and pointed out that Torres was ready to start again “with the youngest, with the purest, free of all contamination and brutalization; not yet deformed by schools emphatic in their mediocrity”18.

These young people, with their diverse experiences, met in the Montevideo locale at 2763 Abayubá St., where the teacher —within his anti-academic “militancy”— proposed a work environment of coexistence. Bearing in mind his desire to integrate all the arts, from architecture to cinematography, Torres taught by means of subject painting —preferably urban and port landscapes—, on which he applied measurement, central perspective, and chromatic and tonal control, proposing exercises with primary colors and with seven tones (the results of which tended towards ochre and earth tones). In line with studies on the constructivist tradition in America, members of the ttg traveled on various occasions to make direct contact with the Indo-American cultures (img. 6) 19.

At the beginning of 1945, the Taller had 92 members, 66 of them disciples, 29 protective members, and 4 honorary members. The internal organization was based on a system of contributions that depended on the financial situation of each member, and Daniel de los Santos was in charge of collecting the funds20. The teaching dynamics consisted of consultation sessions based on the works produced in their own workshops, thus allowing work from students who lived some distance from Montevideo. The exhibitions were numbered consecutively and, beginning in 1945, the ttg had a permanent exhibition hall in the basement of the Salamanca Bookstore. From November 1946, the new teaching room was located in the basement of the Ateneo de Montevideo, inaugurated with an exhibition entitled Pintura y arte nuevo del Uruguay (the Taller’s 35th exhibition) in which more than fifty artists participated with constructive and applied art works21. Later, towards the end of 1950, this place was adopted as the Taller’s exclusive exhibition venue, given the lack of acceptance by the Montevideo cultural scene.

While working for the ttg, the master never interrupted his task of dissemination through lectures and through writing his ideas. Among the main texts, he published Universalismo Constructivo. Contribución a la unificación del arte y la cultura de América (1944), Nueva escuela de arte del Uruguay (1946) —containing a summary of the Taller’s activities and photographs of his works—, Mística de la pintura (1947), Lo aparente y lo concreto en el arte (1947) —a compilation of Torres-García’s lectures given at the School of Humanities and Sciences in 1947— and the classes given at the same School in 1948, compiled under the title La recuperación del objeto.

The integration of art in daily activities

[…] if through man, the Universe becomes conscious, Constructive Art would be a testimony of this. And well, for such reasons, Constructive Art, is, always, for the collectivity: it speaks to all.22

The torresgarciano utopia proposed a recovery of the role that aesthetic productions had in Indo-American cultures, which meant “recovering its old metaphysical-religious function, in which the artist, incorporated into a collective and even anonymous activity —in the words of Juan Fló— enters into communion with the order of the universe and produces work that celebrates that cosmic sense”23. This Constructive Art, then, aspired to be both anonymous and monumental in its relationship with architecture, and to project itself into objects of everyday utility.

On the one hand, for Torres, the teaching of the applied arts derived from the line practiced in 1913 in the decorated handicrafts workshops in the Catalan-Mediterranean tradition that he had taught at the Escola de Decoració de Sarriá. In Montevideo, however, his inclination towards archaic cultures turned towards the study of the Indo-American tradition, with a view to anchoring the new project in these latitudes. In Uruguay, on the other hand, it was embedded in an environment permeated by the ideas of Figari. The latter had already anticipated the importance of training worker-artists in the Reorganization Project at the Escuela Nacional de Artes y Oficios of 1910 and, between 1915-17, put it into practice at the Escuela de Artes y Oficios of Montevideo, where students participated in the entire production process. It also incorporated pre-Hispanic iconography and references to native flora and fauna. However, according to Thiago Rocca, this initiative had met with resistance from political and industrial sectors that were unwilling to encourage an idea that did not favour the interests of importers of furniture and household supplies. And, furthermore, the use of pre-Hispanic iconographic references had sparked controversy about national identity and the nature of autochthonousness24.

Although Torres’ discourse was intended to erase the boundaries between the artist and the artisan, the Taller’s productions had to be inserted into a space strained by the autonomy of the art system, in which paintings entered the fine art circuit, while objects of use made as unique pieces were inscribed in a hybrid space of circulation. It is interesting to note this tension in a request received by Torres himself. Following the publication of Universalismo Constructivo through Poseidón, Joan Merli —the director of that publishing house— commissioned him to decorate his radio and gramophone cabinet, offering to reproduce the work in the two magazines he edited in Buenos Aires —Saber Vivir and Cabalgata— and to exhibit it both at the Iriberri house and in the window of the Galería Müller25. Merli’s letter brought the art circuit closer to a trade specialised in electrical appliances, and transferred the valuation of the artist’s work to the utilitarian object:

I believe that it will spark the curiosity of many people and you will not be wanting for success with this exhibition of applied constructed art. […] I will not bargain with you as if I were rich. I can only express my interest and the pleasure it will be for me to have an appliance like none other for the time being, until after the exhibition, when many will want to have one made by you26.

In his last lessons, the master reflected on this blurred borderline:

He said that Constructive Art could no longer be considered neither painting, nor even art. But, if it is practiced by a painter, can it cease to be painting? We have all seen that this is so; but it was convenient for me to delimit its essence, which must remain as something outside of art; that is to say, of any artistic realization […]. And there would appear to be a contradiction, but such is not the case; all it means is that by entering through art, one must arrive at something that is no longer art, and that, because it is universal (the absolute, the pure), cannot even refer to art itself. […]. It is not, then, an art for an artist to create, like painting, at every moment; nor is it for it to be lavished on this or that wall or object. It has, instead, a religious transcendence, which must be respected27.

The members of the ttg made pieces of Constructive Art with inexpensive materials: wood, leather and brick, or metals and stones in their more accessible variants, and decorated plates or molded jars. Julio Alpuy and Gonzalo Fonseca made inlays using bone, buttons, mother-of-pearl, or even lead sheets from the tubes of their old paints.

Josep Collell and, his wife, Carmen Cano, were outstanding exponents of ceramic work (img. 7 and 11). Collell had been trained at the ttg under the direction of Alpuy; however, the passage from prefabricated plates and vessels to molded pieces occurred alongside Fonseca, when he made a first attempt at firing in a bread oven that the latter had in the Casa-Taller del Cerro, which he shared with Antonio Pezzino and later with José Gurvich. After exploring different coloring combinations, Collell discovered engobe burnishing, whereby he painted the dry, sanded unfired piece with engobe, oiled and burnished it until the color penetrated the clay and, finally, fired it at over 1,000 degrees28. Many artists created Constructive Art on molded ceramic pieces, until they managed to obtain an Italian ceramic kiln (donated by Mr. Carlos Alberto Piria), in which they were able to experiment with molding the pieces and the finishing methods, such as engobes and varnishes for the glossy finish.

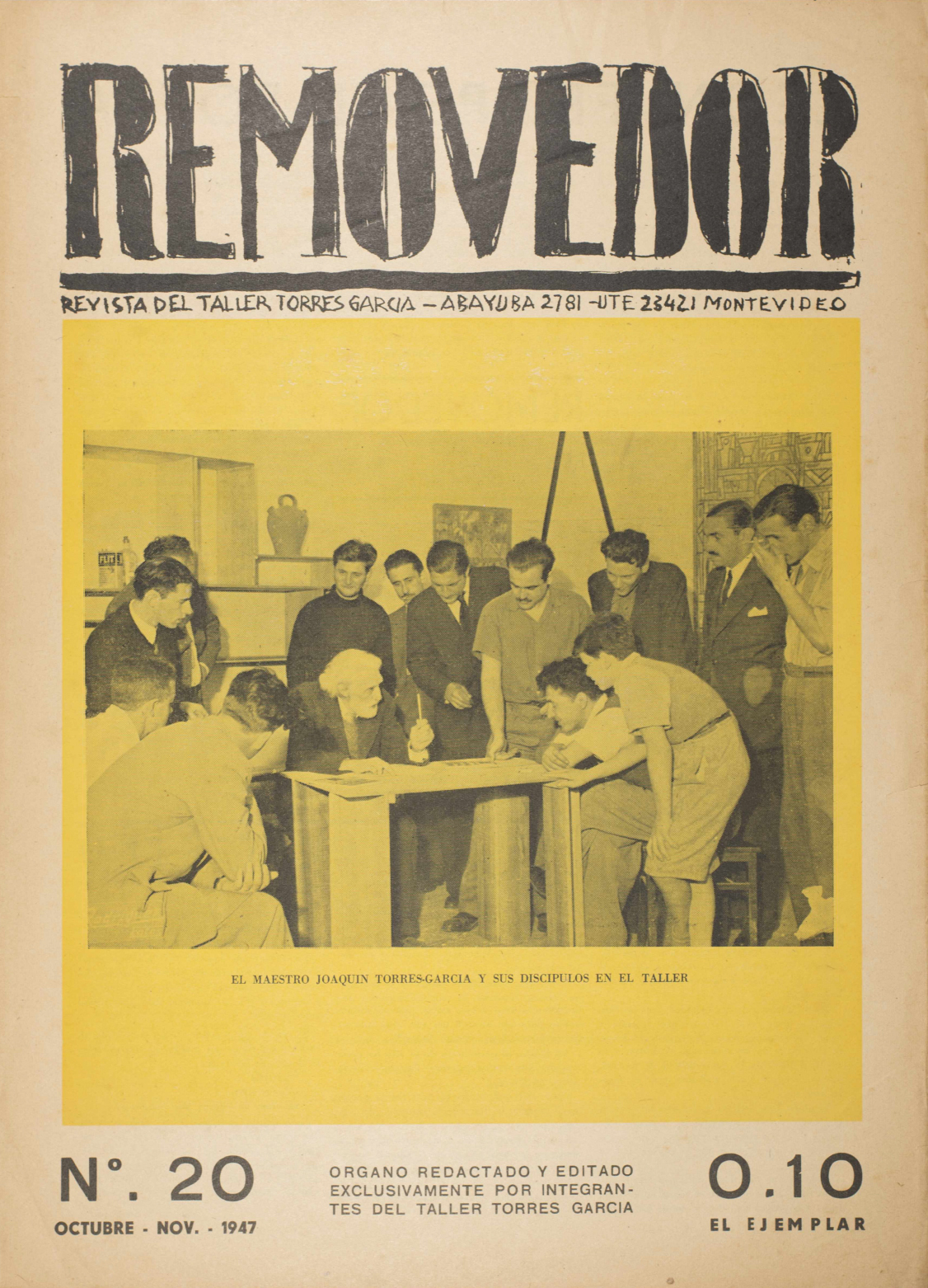

Ever since the appearance of Removedor. Revista del Taller Torres García29, Sarandy Cabrera was in charge of the graphic tasks, a position in which she developed her design skills. Some members of the ttg did graphic work, among which Gurvich and Pezzino illustrated and designed the programs for Cine Club Uruguay. Pezzino designed an enormous variety of posters, album covers, books, logos, postage stamps, commercial brochures, and menus at Imprenta AS, where he was part of the working group made up of Jorge de Arteaga, Nicolás Loureiro, Ayax Barnes, Carlos Pieri, and Hermenegildo Sábat, considered a forerunner to the professionalization of Uruguayan graphic design30.

Image 8.

Removedor. Taller Torres García Magazine, n.º 18, June-July-August,1947 and n.º 20, October-november, 1947, Montevideo

Image 9 and 10.

Antonio Pezzino, Designs from the TTG Exhibition catalog n.º 94 and design for the French Film Festival poster, 1959.

Once the TTG was formed, the master received his first commission for a collective mural: the memorable and controversial project of the Martirené Pavilion of the Saint-Bois Hospital, painted in 1944, which paradoxically, was the only one that was executed due to his intervention. However, beginning in the 1950s, his disciples produced an extensive body of mural work31, generally associated with the work of architects close to his environment. Ernesto Leborgne, Juan Ramón Menchaca, Román Fresnedo Siri, Florio Parpagnoli, Luis San Vicente, Juan Scasso, Sara Morialdo, and Carlos A. Surraco had approached him early on, followed later by others such as Mario Payssé Reyes, Antonio Bonet, and Rafael Lorente Escudero, among others. Certainly, the muralist production —for which different techniques and materials has to be used— required time for the disciples to mature in their learning, which is why the projects were destined to find better conditions for their implementation no earlier than the 1950s, when Torres was no longer in a position to work on them32.

Prominent among the jewelry crafts were the silver jewelry pieces made by Olga Piria, and Augusto and Horacio Torres. Arquivaldo Almada, Gastón Olalde, Carlos Llanos, Huidobro Almada, Jorge and Rodolfo Visca founded the Taller Sótano Sur in 1956. The group also organised workshops to teach ceramics, wood carving, and stone and metal work, especially copper enameling.

maotima, a group integrated by Manolita de Torres, Otilia, Ifigenia Torres and María Angélica, from whose initials it took its name, was created around 1950. Under the coordination of Torres García’s widow, the group made hand-embroidered tapestries based on constructive works, while Elsa Andrada also weaved tapestries on a loom, such as the one in Mario Payssé Reyes’ house, based on a design by Augusto Torres.

This brief overview —not intended as a complete tour— evinces the practice of Constructive Art according to the established program. However, these pieces —not conceived as a unique production that did not admit a serial process— did not reach a wider circulation in society during the most productive years of the ttg. It is also true that there was a space for dialogue with architects that emphasised the concept of integration between constructive expressions and the architectural project, although these opportunities could not go beyond the confines of those who were already familiar with Torres García’s ideas.

Image 12.

Manolita Torres interview where you can see the radio painted and engraved by Torres García (Mérica, Ramón, “Construir una vida”, El País, Montevideo, 26-03-1972)

Image 13.

José Gurvich, Caja Construida III, c. 1957. Oil on Wood, 9 × 19 × 5 cm. Gurvich Museum Colection, Montevideo.

Image 14.

Augusto Torres, tapestry design made on a loom by Elsa Andrada, located in the Paysée Reyes house. Photography Gustavo Serra.

The Rioplatense Constructive Will: The concretism of the AACI and the MADI group

Inventionism energetically denies all melancholy, exalts the human condition, fraternity, creative joy, and supports its faith in a definition of reality.

Edgar Bayley (1945)

The Argentine cultural scene of the late 1930s was dominated by figurative art, be it naturalist, symbolist, realist, or surrealist. By 1936, Antonio Berni had formulated his notion of “new realism”33, and as of 1938, the members of the Orion group were delving into the unconscious and forms arising from fantasy34. The most socially relevant aspect maintained a degree of predominance in the art scene: Berni won the Honorary Prize at the 1943 National Salon, while the commission for a mural for the entrance and dome of an emblematic Galerías Pacífico building in Buenos Aires, was awarded to the Taller de Arte Mural, formed in 1944 by Juan Carlos Castagnino, Lino Enea Spilimbergo, Demetrio Urruchúa, Manuel Colmeiro, and Berni himself.

Artistic education at that time still followed an academicism linked to the copying of ornaments and plaster models that led to deep dissatisfaction among the young eager for novelty. In 1942, a small group of students —formed by Jorge Brito, Alfredo Hlito, Claudio Girola and Tomás Maldonado— expressed their rebelliousness through the “Manifesto of Four Young Men”. Although the text was pronounced against the juries and the winners of the National Salon, the actions tried to join the whole student body to deepen the protest against the artistic education system. Although they did not succeed in gaining collective support, the radicalization of their position led them to leave the classrooms of the Prilidiano Pueyrredón National School of Fine Arts35.

Their names soon reappeared at another disruptive time, when the first issue of Arturo magazine was published in April 1944. Arturo was an abstract arts magazine for which they had secured collaborations with the Brazilian modernist poet Murilo Mendes, the Chilean Vicente Huidobro, and Torres García36. The magazine launched an inventionist proposal, which, based on Marxist dialectics, was intended to sweep away primitivism, realism, and symbolism37. The young people who united around Arturo exhibited their works for the first time towards the end of 1945 under the name of Movimiento de Arte Concreto Invención (maci), on soirées that included music, dance, architecture, photography, literature, and plastic arts presented at the residence of the Aberastury-Pichón Rivière couple and, later, at the house of the photographer Grete Stern38. Two groups were formed following these first presentations: the Asociación de Arte Concreto Invención (aaci) made up of Maldonado, Hlito, Girola, Edgar Bayley, Lidy Prati, Manuel Espinosa, Enio Iommi, Juan Melé, Gregorio Vardanega, Virgilio Villalba, Antonio Caraduje, Simón Contreras, Obdulio Landi, Raúl Lozza, Rembrandt van Dyck Lozza, Alberto Molenberg, Primaldo Mónaco, Oscar Núñez, and Jorge Souza; and the madi Movement formed by Arden Quin, Rhod Rothfuss, Gyula Kosice, Martín Blaszko, Diyi Laañ, Elizabeth Steiner, musician Esteban Eitler, Valdo W Longo, Ricardo Humbert, Alejandro Havas, Dieudonné Costes, Raymundo Rasas Pét, Sylwan Joffe Lemme, and Paulina Ossona.

In those early days, the aesthetic program of both groups consisted in working on invented shapes painted with flat colors, inscribed in cut-out frames —an idea anticipated by Rothfuss in Arturo, which proposed the abandonment of the Renaissance window in favor of irregular formats, in which the frame was adapted to the shapes it contained— and co-planar, for which they painted triangles, squares, circles, and even irregular polygons on wood, cut them out and joined them with rods to place them directly on the wall. The sculptures privileged the work with flat volumes, and simple geometric surfaces or lines traced with metal rods.

Both the co-planar and madi sculptures incorporated the mobile articulation of the pieces that made them up and the possibility of their activation, a participatory principle that expressed the desire for a transformative relationship as they wrote in their program: “Our art is human, deeply human, because it is the person in all his essence who consciously creates, makes, builds, and actually invents”39.

While in response to the need for revolution, the aaci brought the applied arts closer to concrete invention in order to project itself through: “The creation of new art objects that act and participate in the integral life of the people and contribute to revolutionize their conditions of existence”40.

Image 18.

Raúl Lozza, Relief N ° 30, 1946. Oil, alkyd, pine resin, wax and acrylic on wood and metal wire, 41.9 × 53.7 × 2.7 cm. Collection Museum of Modern Art of New York (Patricia Phelps de Cisneros Donation).

Image 19.

Diyi Laañ, Madí Painting on structured frame, 1949. Painting on wood, 82.5 × 57 × 1.3 cm. Museum of Latin American Art of Buenos Aires (Malba)

Image 20.

Martin Blaszko. Structure or White Lights, 1947. Technique: Oil on canvas mounted on hardboard, 112.5 × 51.5 cm. Museum of Latin American Art of Buenos Aires (Malba).

Image 21.

Armelo Arden Quin, Coplanal with variable geometry mist, 1945. Lacquer on wood, variable measures.

Image 22.

Gyula Kosice, Röyi N ° 2, 1944. Wood (articulated sculpture), 70.5 × 81 × 15.5 cm. Museum of Latin American Art of Buenos Aires (Malba)

As many concrete artists had joined the Argentine Communist Party (pca), whose ranks also included artists who defended the new realism, this art of invention, which presented concrete forms in opposition to the illusory representation of reality practiced by the figurative artists who dominated the local scene, soon provoked heated aesthetic-political debates. In fact, the “Defense of Realism” by Héctor P. Agosti —an organic intellectual of the pca— was published before the end of 1944, after which the Buenos Aires magazine Contrapunto published a survey asking ¿Adónde va la pintura? or where is painting going, which, in turn, reedited the debate opened in Paris when, in 1935, some artists of the historical avant-gardes had taken a stand against socialist realism. In Buenos Aires, the survey was distributed in several installments, in the first of which, the voices of the acclaimed Berni and the young emerging Maldonado confronted each other41.

However, in 1947, the Soviet demand for realignment on the canon of socialist realism strained the discussions within the pca and broke the tolerance they had shown towards individual artists who were members of their ranks. For those who had considered it essential to unite political transformation with esthetics, the party breakup dealt a hard blow to the expectations of art’s reinsertion into vital praxis. Towards the end of 1947, other reasons contributed to the loss of group cohesion: internal leadership disputes worsened, and post-war reconstruction made travel possible allowing some artists to leave to visit the museums and workshops of European avant-gardists42.

Image 23.

“Where is painting going?”, Contrapunto, Buenos Aires, year 1, No. 4, June 1945, pp. 10-11

Image 24.

Cover of the survey: “Où va la peinture ?, Commune, revue de l’Association des Écrivains et des Artistes Revolutionaires, vol. 21, Paris, May 1935, p. 937

It is interesting to note that while these dismemberments were transforming the physiognomy of the initial groups43, a regrouping began, foreshadowed by the two exhibitions that in 1947 brought together works by some members of the aaci and the madi group along with many other artists interested in expressing themselves through the “new art” of those days44. Moreover, as Maldonado wrote in 1949, just as breaking with militancy did not necessarily imply the abandonment of political ideals, neither did the cracks imply a resignation of the desire to recover the social function of art:

But just as “the political” will be overcome by the total politicization of man, so “the artistic” will only disappear when art manages to expand to such an extent that even the most remote and secret areas of daily life can be aesthetically fertilized45.

Thus, between the end of the 1940s and the beginning of the 1950s, a pleiad of artists played a leading role in the consolidation and expansion of abstract language. When speaking of modern art, non-figurative art was alluded to, but the works that conformed to the orthodoxy of the concrete art program were already sharing the stage with abstraction of a free and lyrical nature. Despite the growing enthusiasm for implementing the “new realities”46 of the postwar period, modern artists had to face the indifference of a public that still demanded to recognize what was represented. In fact, each public appearance of “new art” renewed the critics’ interest in debating whether to speak of non-figurative, non-objective, concrete, or abstract art, while the official speeches of Dr. Oscar Ivanissevich —Minister of Education— qualified it as morbid and perverse art47. As a result, abstract artists banded together to confront the onslaught; agreed on strategies to obtain venues to exhibit and to attract the attention of critics; and, in some cases, founded their own magazines to disseminate their ideas.

Image 26.

Cover of Bulletin 2 of the Center of Students of Architecture. CEA 2, no. 2, Oct-Nov, pp. 7-8, Buenos Aires

At the beginning of the decade, in addition to the new conformations adopted by the groups that had spearheaded the vanguard, Grupo Joven, founded in 1946 by Víctor Magariños D.48 and the Perceptista group, created by the Lozza brothers when the aaci disbanded, were still active. In 1952, the initiative of two critics led to the creation of the Grupo de Artistas Modernos de la Argentina (gama), promoted by Aldo Pellegrini, and 20 Pintores y Escultores, founded by Ernesto B. Rodriguez. The artists also joined forces to strengthen their insertion in the circuit by founding the Asociación Arte Nuevo (an)49 and Artistas no Figurativos de la Argentina. The artistic world then entered a phase marked by the consolidation and expansion of abstraction that deepened autonomization, while the collective utopian impulse faded away.

A time of transition: From applied arts to design

I had wanted an avant-garde that would transform all of reality and I had to be content with a purely artistic avant-garde; that is, an avant-garde dedicated solely to modernising the old institution called ‘art’.

Tomás Maldonado50

In the late 1930s, Ignacio Pirovano paved the way for the members of the Orion group to set up a workshop in Villa Devoto to meet both the needs of the industry and the demands of high-end decor (Rossi, 2012)51. Pirovano was part of the Comte corporation that produced and marketed furniture and decorative objects; and between 1937 and 1956, he served as the director of the National Museum of Decorative Art. Interested in renewing the design of furniture and high-end decor, he entrusted the task to artists according to their expertise: from the members of the Orión group to the French interior designer, Jean Michel Frank. Along the same lines were his interventions in the Salones de Artistas Decoradores, whether as an organizer and juror, or as a participant through Comte S.A., which sent an Un living room created with the collaboration of Antonio Berni and Taller Orión to the IV Salon.

Begining in the last quarter of 1946, Ernesto B. Rodriguez —poet, critic, and member of Orión— served as editor and collaborator of the Boletín del Museo Nacional de Arte Decorativo and of publications by the Comisión Nacional de Cultura. Under Pirovano’s management, Rodriguez was involved in the design of a school of decorative art that would operate in the museum and which was intended to bring together “from the creation of a dress to urbanization; from the binding of a book to architectural decoration, from the conception of a jewel to the style of a piece of furniture”. The training was to be offered to graduates of the Escuela Nacional de Artes Visuales and the Escuelas de Artes y Oficios, as well as to untrained people who had to sit a theoretical test, and it was planned to start with a seminar52. At the head of the National Commission of Culture between 1951 and 1953, Pirovano promoted an Industrial Design Subcommittee involving Maldonado, Hlito, Francisco Bullrich and Juan Manuel Borthagaray, among others.

From applied arts to signature design, in those years, Constructive Artists were engaged in graphic design and the production of objects of use. In 1949, when addressing the status of art in society, Maldonado considered that design was “the only real option we have, to solve, on an effective level, the most dramatic and acute problem of the spirit of our time; that is, the existing division between art and life”53. In fact, he himself designed the newsletter in which these ideas were published, in din A4 format and with the typography he had brought from Europe. He also designed the cover for the book Estereopoemas de Bajarlía, programs and catalogs, and, together with Hlito, he designed the magazine Ciclo. Arte, literatura y pensamiento moderno. Between 1951 and 1953 Carlos Méndez Mosquera, Hlito, and Maldonado founded the Axis agency, dedicated to graphic design and visual communication. The graphics of the Krayd Gallery were successively entrusted to Maldonado, Tomás Gonda, and Hlito, although it was with the latter’s intervention that a graphic style was established for the formats and each exhibition featured full colour54. Prati designed graphic pieces and typography for some exhibitions, in collaboration with the Amancio Williams architect’s studio, as well as the layout for magazines such as Mundo Argentino, Lyra, and Artinf55, and, towards the end of the decade, Villalba designed several covers for Estrategia56.

Many of the members of Grupo Joven engaged in object design or took on graphic tasks including layout and illustration for periodicals, catalogs, posters, or advertising pieces. Magariños D. made sketches for textile printing, conceived ceramic molding jars and plate decorations, and designed bijouterie and tables and floor lamps to be cast in bronze. Miguel Ángel Vidal, Eduardo Mac Entyre, and Alfredo Carracedo also created designs for ceramics, bath screens, and textiles. The latter, together with Jorge Ciaglia and Héctor Buigues, worked on pieces of utilitarian ceramics manufactured by the Arganat company, which were exhibited in December 1953 at the Salón Peuser57. Sarah Grilo, Fernández Muro, Miguel Ocampo and Hlito worked on textile designs for Buen Diseño (img. 30 y 31) (bd), a project managed by Jacobo Soifer, in which Iommi also designed jewelry (img. 32 y 33). In her study Buen Diseño para la industria or Good Design for Industry, María José Herrera (2006) pointed out that these designs were printed between 1954 and 1956 by the companies Italar, Celaco, Sudamtex, and Lanera San Blas58. In partnership with German architect Hermann Loos, Iommi began to produce interior decorations in 1956, an Architectural Office for which Emilio Renart made polyester objects59.

Image 28.

Victor Magariños D., Design for bijouterie. Graphite and tempera on paper, 11.5 × 27.5 cm. Particular collection.

Image 29.

Victor Magariños D., Design for two-mouth jug, Graphite on 17.6 × 10 cm paper. Private collection.

This brief and by no means exhaustive review, shows the artists’ enthusiasm at a time when advances in science and techniques developed during the war were available for industrial application, and pushed the possibilities for design. In 1950 and after contacting Max Bill, Pirovano began planning an exhibition that aspired to “make Argentine manufacturers and consumers understand the functional, technical, and aesthetic advantages of the ‘designed product’ or, in other words, of ‘industrial design’”60. It was a display of the “good form” which, following Bill and Will Burtin’s conception, projected an organization by contrasting natural or scientific, and everyday or industrial forms.

Image 32.

Enio Iommi, Design for jewelery made in silver. Private Collection. Fotography: Leonardo Antoniadis

Image 33.

Enio Iommi, Design for jewelery made in silver. Private Collection. Fotography: Leonardo Antoniadis

Bill had conceived the notion of good form (Gute Form) as a general principle that crossed the entire material universe and was not even exclusive to the field of product form (Produktform). By the middle of the decade, as pointed out by Alejandro Crispiani, Maldonado agreed with Bill’s idea of good form, and with his critique of the technical object considered merchandise; in other words, they agreed on the risk that the logic of profit would end up deforming objects61.

Those were times in which the art-design binomial was a tense one. In this context, the magazine Nueva Visión published an article by Georges Nelson (1953) that traced the genesis of designers in relation to the increase in sales that occurred as a result of subjecting products to a “series of beauty treatments”62. The magazine circulated —not just in this case— not only ideas about the artist’s task in the manufacture of products, the dynamization of the market, and the designer’s profession. These readings stirred agreements and disagreements, at the same time as they raised the tone of some opinions. In fact, Magariños D. commented and discussed Nelson’s article, because in his opinion, the dissemination of industrial products led to a “relaxation of their qualitative values” and he considered that industrial design ideas posed a threat to the stability of creative energy63.

In 1954, Maldonado was invited to teach at the Hochschule für Geltaltung (HfG) and decided to leave for Ulm. In writing his farewell speech, Pirovano emphasised that he was leaving for Germany where he would represent Argentina in this “transcendent artistic-cultural experiment of our time” that followed in the footsteps of the Bauhaus64. However, the project soon suffered a change of direction: on the one hand, at the end of Bill’s period of direction, a collegiate rectorate was formed by Olt Aicher, Hans Gugelot, and Maldonado. On the other, around 1955, the Billian notion of good form began to be questioned, since Maldonado and Aicher considered it irrelevant to talk about form in light of post-war technological progress, because technology had already demonstrated greater flexibility and the criteria of economy were more complex than they had been in the Bauhaus period.

By way of conclusion

Industrial design is not an art and the designer is not necessarily an artist.

Tomás Maldonado (1958)

While the point of departure for the concrete avant-garde was based on the developments of European concretism and considered itself called upon to intervene in the time of reconstruction, Torres García based his program on the Indo-American tradition –as one of the versions of the universal tradition— and his utopia attempted to recover the connection of art with the rites and practices that integrate a culture with the cosmic order.

In questioning the art history-based perspective that argued that Torres-Garcia’s proposal fuses pre-Columbian art and European modern art in its most radical purist line65, Fló (2006) analysed Torres’ approach to Mondrian’s neoplasticism, with whom he had shared an inclination towards theosophy. He pointed out that although this friendship prompted him to produce some abstract works, the most important thing was that it fuelled his questions about whether art would dissolve into the rational world of the future, or whether it would fuse with the instinctive world of primitive societies governed by religion. The author then argued that his encounter with Mondrian spurred him to produce a synthesis that would take modern art out of the aestheticist path into which it had fallen, and stressed that it was the meeting of two opposing utopias:

Mondrian’s utopia, in which art opened the way to a future in which art would be so embedded in life that it could not be something independent, and Torres’s utopia of an art that, unlike aestheticist modern art, embarked on a dead-end path, should reinstate the lost foundation of its participation in a cosmic order66

In later years, the master continued to strive to impregnate the living environment and, although he expected to have the opportunity “to make definitive works, be they mural paintings or stained-glass windows, stone and wood sculptures, graphic decorations, etc.”, in the same lesson he recognised that:

All those who attended the Taller worked on both Painting and Constructive Art. But, if we look at their exhibitions, which of the two paintings has won? Everyone can answer this without hesitation: Painting has won.67

It was only after his death, in 1949, that his disciples’ constructive painting managed to transit its expected passage towards monumental work and, associated with the work of architects, decanted into projects that provided comprehensive solutions, while also expanding the production opportunities for applied arts. However, these utilitarian pieces produced as unique works by the artists —situated in an ambiguous zone with respect to anonymous collectivism and the alleged rupture of autonomy— had to contend with the challenges of insertion into the rituals and practices of community life.

Although the young inventionists who promoted Arturo magazine initially approached Torres García, as their avant-garde discourses matured —in terms of both the program of their works and their theoretical productions, as well as their political positions— they had already distanced themselves from him. In line with the Russian constructivists who had transferred their utopian ideas to prototypes and sensible forms to foster the social transformations they postulated by means of analogy, madi artists proposed a transformative vision linked to anticipatory imagination, in which freedom operated in the creative moment and in the transformation of man through his participatory activity. In turn, the members of the aaci subscribed to the desire to surround man with real things, and even affirmed: “The era that is about to begin, an era of reconstruction and Socialism, demands an art in keeping with the material life of the society that is born and develops”68. However, the attempt at direct intervention in everyday reality as a form of dissolution of the artistic, comparable to the aspiration of a society without classes or private property, did not lead to a proposal that solved the division between art and life in the group work period.

In the second half of the 1950s, the design field began to be institutionalised, which would displace artists’ work in the field of applied arts and signature designs. The transition towards the formalization of design knowledge in Buenos Aires coexisted with the student rebellion in which students took over the three schools of fine arts on October 3, 1955, in an attempt to transform art training into university education, renew study plans, and remove a significant portion of the teaching staff.

After three long years of complaints, in 1958, new curricula were approved for the three schools of fine arts that included the teaching of industrial design, as the nature of the problem of design and its techniques was considered to be closely linked to visual expressions (painting and sculpture) and architecture. However, the Plan Review Committee recommended delaying its implementation in view of the need for a team of teachers and adequate workshops and facilities. A three-stage action plan was proposed to organize the School of Design and the Research Institute. It called for the formation of working committees, the holding of introductory seminars for students and specialised seminars for the training of future professors, as well as the establishment of a network of connections and interdependencies with institutions and chambers of industry69. However, in light of the new approaches, these efforts soon had to be reassessed.

In fact, that same year, Maldonado presented the text Nuevos desarrollos en la industria y en la formación de diseñadores de productos (New Developments in Industry and in the Training of Product Designers) at the Brussels World’s Fair70. In it, he proposed an interdisciplinary perspective that would respond to the needs of industrial-scale production and synthesised a concept of designer that, as it matured, differed radically from the Bauhausian one that Bill had upheld. He then stressed the need to move away from the affiliation with the “Arts and Crafts” movement, which meant rejecting the priority of the aesthetic factor in design. But he also proposed to review the importance of the rationalist aesthetics of industrial production of the Bauhaus School, because by placing the question of artistically resolved form at the centre, it posed the risk of stagnating in academic formalism71.

The first university design education projects were influenced by the concrete ideology, although they were anchored in spaces of exchange with other disciplines, as in the case of the role assumed by Girola at the School of Architecture at Universidad Católica de Valparaíso72. Universidad de Cuyo in Argentina established its School of Design and Decoration in 1958, with contributions by architect César Jannello, artist Abdulio Giudici and architect and ceramist Colette Boccara since they joined the School of Art of Mendoza73. Similarly, for the Design Program at Universidad de La Plata, Villalba’s name was recognised as a driving force in the dissemination of the avant-garde spirit of concrete art74, as has the influence of the lecture given by Maldonado on directing the guidelines adopted by its programs and the creation of the Instituto de Investigaciones y Servicios en Diseño Industrial (Industrial Design Research and Services Institute)75(img. 34). Verónica Devalle’s study on graphic design considered the early contributions of concretism and modern architecture, although she pointed out that professionalization only took place following the opening of industries and the growth of markets in the 1960s, when the social agenda focused on the problem of communication76.

In Argentina’s transition from applied arts to incipient design, Pirovano was a catalyst who played a pivotal role in between tradition and innovation. Arguably, when he travelled to Germany in 1962 to visit the HfG —together with the entourage consisting of Blas González, Jorge Romero Brest, Amancio Williams, and Kenneth Kemble77— he was closing the circle of a transition phase he had been involved in since the 1930s. Permeable to change, he acknowledged that Maldonado and Williams had shown him that in the industrial era —as we moved from artisanal work arising from the hand of man to industrial work carried out through machines created by man— designs had been transformed into areas that exceeded the limits of training in art schools and the work of artists.

Indeed, Boris Groys argued that modern design brought about a radical change that disrupted the tradition of the applied arts and imposed a new paradigm. To express the transformative potential, he resorted to the image of the New Man who, invited by the apostle Paul, took off the clothes of the “old man” to cover himself with the garments of the subject that would embody the new utopia78. The paths we follow in the Rio de la Plata area show that, as pointed out by this author, the stripping of the nature of the applied arts needed to reach the “essence” of the objects, implied both a shedding of the ornamental mantle that covered them, and a new direction to the utopian horizon to achieve their reinsertion in the vital praxis of the time of post-war reconstruction.