In 1953, when the philosopher Martin Heidegger wrote “The Question Concerning Technology” (published in 1954), the US and the Soviet Union tested the first hydrogen bombs, triggering the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists to recalibrate the Doomsday Clock to advance to two minutes before midnight, the closest it had ever been to nuclear Armageddon. For the first time since that era, in 2018 the Doomsday Clock again advanced to two minutes before midnight. In 2020 it moved to just one hundred seconds before midnight, where it remained in 2021 and 2022. We are now closer to apocalypse than at any prior time in history.1

Art offers Heidegger hope for salvation from technology’s dehumanizing effects. He writes: “Man stands so decisively in subservience to the challenging-forth [Herausfordern] of [technological] enframing [Gestell] that he […] fails to see himself as the one spoken to […].”2 He then adds: “the actual threat has already afflicted man in his essence.”3 Just when it appears that all hope is lost, the philosopher notes that in ancient Greece “the bringing-forth of the true into the beautiful was called techne. And the poiesis of the fine arts was also called techne.”4 Whereas technological enframing “threatens revealing” and “radically endangers the relation to the essence of truth,” Heidegger proposes that the “fine arts are called to poetic revealing,” and that they constitute a “saving power” that “shines forth […] in the midst of the extreme danger.”5

In more direct terms, the art historian and critic Jack Burnham observed that “[w]ith increasing aggressiveness, one of the artist’s functions […] is to specify how technology uses us.”6 Burnham argued, moreover, for the crucial importance of art as a means of survival in an overly rationalized society. Indeed, like many intellectuals in the 1960s, he feared that the cultural obsession with, and faith in, science and technology would lead to the demise of human civilization. Burnham proposed that an “increasing general systems consciousness” may convince us that our “desire to transcend ourselves” through technology is “merely a large-scale deathwish,” and that ultimately “the outermost limits of reasoning” are not reachable by post-human technology but “fall eternally within the boundaries of life.”7 Along these lines, composer David Dunn more recently suggested that music might serve a unique evolutionary function that can “provide us with clues to our continued survival.”8 In 2016, he was awarded a patent for a device that uses “acoustics to disrupt and deter wood-infesting insects and other invertebrates from and within trees and wood products,” which has the potential to stem a cycle of bark-beetle infestation, forest fires, and global warming.9

The philosopher Alva Noë argues that art is “an engagement with the ways in which our practices, techniques, and technologies, organize us,” and “a way to understand that organization and, inevitably, to reorganize ourselves.”10 For Noë, dancing, singing, and making pictures shape us as human beings; however, they are not art, per se. Art defamiliarizes these practices, revealing their organization and making them strange. Art, for Noë, is therefore a “strange tool” that we use to investigate the things we do and how our technological nature shapes the way we are. In this respect, art functions in ways that may potentially undermine the threats perceived by Heidegger and others, enabling us to reshape ourselves in ways that are not enframed by technology.

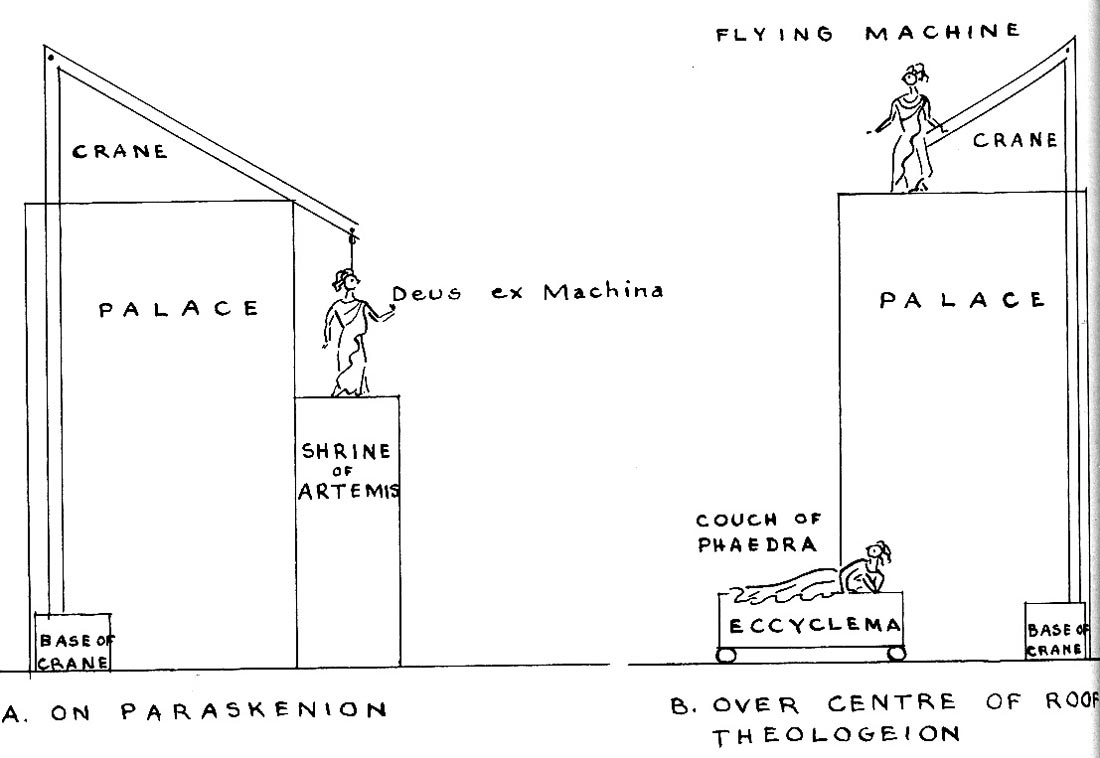

In ancient Greek and Roman drama, the deus ex machina marked the appearance, suspended from a crane, of a god-like figure that resolved a dilemma. More generally, the term refers to a person or thing that appears suddenly and unexpectedly and provides a contrived solution to an apparently insoluble difficulty. In the past, I dismissed Heidegger’s poetic retreat to art as a form of deus ex machina. In “The Question Concerning Technology” he unexpectedly contrives a deus ex poiesis to liberate us from the insoluble difficulties—metaphysical and epistemological—caused by technology. According to philosopher Philippe Lacoue-Labarthe: “With the failure of the project of self-affirmation (Selbstbehauptung) of the University and, thereby, of Germany itself, science (which supported this whole project) gives way to art, in this case to poetic thought.”11 It is easy enough to understand why in the physical, moral, and emotional rubble of post-WWII Germany, Heidegger, like other intellectuals of the time, was grasping at straws to breathe hope in a sea of nihilism. It was imperative to transcend the scientific mind-set that enabled advanced technology to reach unprecedented levels of destructiveness but that was unable to muster the compassion required to prevent that destruction.

Image 1.

Deus ex machina graphic. Margarete Bieber, The History of the Greek and Roman Theatre. Princeton and New Jersey, 1939, p 76.

The polymath cybernetician Gregory Bateson once remarked: “mere purposive rationality unaided by such phenomena as art, religion, dream, and the like, is necessarily pathogenic and destructive of life; […] its virulence springs specifically from the circumstance that life depends upon interlocking circuits of contingency, while consciousness can see only such short arcs of such circuits as human purpose may direct.”12 The sort of purposive rationality referred to by Bateson finds its apotheosis in the logics of neoliberal capitalism, whereby social value is determined by market value, growth is taken as a given, efficiency is worshipped, and privatization is embraced as a panacea.

Whereas scientists generally use the term “Anthropocene” to refer to the human impact on the environment with respect to climate change, human ecologist Andreas Malm coined the term “Capitalocene” to identify a web of forces associated with the complicity of capitalism and fossil fuel extraction at the root of global warming. Building on these ideas, the feminist multispecies theorist Donna Haraway coined the term “Chthulucene” to identify a broader and more complexly entangled field, highlighting the inextricability of human and non-human actors. She argues that capitalism’s “endless growth, extraction, and the production of ever-new forms of inequality” comprise a “vastly destructive process, whether you’re talking about social systems or natural systems.” Mindful of the complicity of language and disciplinary metaphors in promulgating these circumstances, Haraway writes in a style that is simultaneously erudite and poetic, creating new metaphors by joining art, science, and philosophy. She advocates a concept of kinship or “making kin” that joins all beings: “all earthlings are kin in the deepest sense […]. All critters share a common ‘flesh,’ laterally, semiotically, and genealogically.” She applies the term “sym-poietic” to emphasize the collective process of poetic emergence in which all beings are collaborators in the process of the Earth’s becoming. “Who and whatever we are, we need to make-with—become-with, compose-with […].” Taking care of the Earth, for Haraway, demands caring for the diversity of beings, and “multispecies ecojustice” must be not only a goal but a means to living well, together, as kin. By “staying with the trouble,” she proposes, “[m]aybe, but only maybe, and only with intense commitment and collaborative work and play with other terrans [inhabitants of Earth], flourishing for rich multispecies assemblages that include people will be possible.”13

The problem with academia is, well, that it’s just too academic.14 I’m trying to heal myself from many years of training and professional activity that have emphasized rigorous analytic thinking to the detriment of other forms of knowing and understanding. Notwithstanding Foucault’s argument that “critique should be an instrument for those who fight, those who resist and refuse what is,”15 academia is out of balance. Its intellectual brilliance and bravura do little to develop the vital abilities that may be necessary for long-term survival. By emphasizing scientific rationality to the detriment of cultivating sensitivity, empathy, and love, academia erodes our ability to be open-minded and openhearted, to embrace all beings as kin, and to accept things that lie outside the realm of reason and logic. As Mary Catherine Bateson wrote: “To learn to love, we would need to recognize ourselves as systems, the beloved as systemic, similar and lovely in complexity, and to see ourselves at the same time as merged in a single system with the beloved.”16 Even if recent tensions over nuclear weapons are ameliorated, climate change threatens to devastate not just human life but vast ecosystems, including millions of species on Earth. And the impact of one hundred years of the Anthropocene-Capitalocene-Chthulucene epoch may last two hundred thousand years, which is as long as Homo sapiens has been on the planet! Yet, we humans, despite our keen rational minds and extraordinary technologies, seem utterly incapable of loving ourselves enough, much less our non-human kin, to protect our shared ecosystems from the impending apocalypse we have set in motion. What is wrong with us? How can art help? Gregory Bateson proposed that “if art has a positive function in maintaining […] ‘wisdom’, i.e., in correcting a too purposive view of life and making the view more systemic, then the question becomes: What sorts of correction in the direction of wisdom would be achieved by creating or viewing this work of art?”17

In the midst of the Cold War in the 1950s, the US and Canada built the Distant Early Warning Line, known as the DEW Line, a system of radar stations to detect incoming Soviet bombers. The Canadian media theorist Marshall McLuhan famously used the DEW line as a metaphor for the role of artists in society. As he wrote in 1964: “I think of art, at its most significant, as a DEW line, a Distant Early Warning system that can always be relied on to tell the old culture what is beginning to happen to it.”18 This sentiment echoes an earlier observation by Walter Benjamin, who wrote in the 1930s: “It is well known that art will often—for example, in pictures—precede the perceptible reality by years […]. Whoever understands how to read these semaphores in advance not only knows about currents in the arts but also about legal codes, wars, and revolutions.”19 Similarly, Burnham thought of art as a “psychic dress rehearsal for the future,” and he considered artists to be “deviation amplifying systems” that are “compelled to reveal psychic truths at the expense of the existing societal homeostasis.”20

Let’s presume that Heidegger was right—or at least that he was onto something. In light of the precarity of the future of life on Earth, what role might art and artists play in pushing the Doomsday Clock back to less threatening levels? In what ways can art show, as Burnham noted, “how technology uses us” or amplify deviations to “reveal psychic truths”? Following Noë, what “strange tools” can artists fashion to investigate ourselves and our technological nature? Or echoing Bateson: How can art correct an overly purposive mindset and promote a more systemic perspective? What sorts of “wisdom” can it impart? How can artists now and in the future help balance analytic thinking with other forms of knowledge production that develop sensitivity, empathy, and love, and that expand our ability to be open to, and to accept, things that lie outside the realm of reason and logic? How can we, as Benjamin intimates, “read these semaphores” to gain a glimpse of the future?

Throughout the history of Western art, those artists who were most concerned with the future informed their work with the latest developments in science and technology. At times they undertook novel scientific research and developed new technologies in order to realize their visions. Bridging the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, the British artist Roy Ascott is one such visionary who creates artistic models that enable us to sample possible futures in the present.21 Profoundly influenced by cybernetics, by the mid-1960s he already had envisioned remote interdisciplinary research collaborations via multimedia teleconferencing: “An artist could be brought right into the working studio of other artists […] however far apart in the world […] they may separately be located […]. [I]nstant transmission of facsimiles of their artwork could be effected and visual discussion in a creative context would be maintained […]. [D]istinguished minds in all fields of art and science could be contacted and linked […].”22

Image 2.

Doomsday ClockSuzet McKinney, member of the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists’ Science and Security Board (SASB), and Daniel Holz, 2022 co-chair of the Bulletin’s SASB, reveal the 2022 time on the Doomsday Clock. (Thomas Gaulkin/Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists)

In 1983 Ascott realized a seminal work of telematic art, La Plissure du Texte. This collaborative, online storytelling project joined artists in eleven cities around the world via a computer network. Using a model that Ascott theorized as “distributed authorship” each node took on an identity (e.g. witch, princess, sorcerer) and together they collectively wrote a “planetary fairytale.” Ascott experienced a sort of collective consciousness that emerged among the participants during the process of generating an unfolding narrative that could not have been produced by a single mind. The technology was primitive by today’s standards and the output was limited to printed ASCII text. Nonetheless, this “psychic dress rehearsal for the future” offered participants an unprecedented opportunity to experience forms of role playing, virtual presence, hive mind, and crowdsourcing that are hallmarks of social media and participatory culture since the mid-2000s. Following a similar trajectory, the American composer Pauline Oliveros was a pioneer of electronic music and multimedia performance in the 1960s and, as a leading practitioner of telematic music performance since the early 1990s, explored and expanded the possibilities of collective sonic consciousness through remote group improvisation.

Despite the utopian rhetoric that heralded the advent of the World Wide Web in the 1990s, the Internet is clearly a double-edged sword. The 2021 Doomsday Clock attributed our current, unprecedented state of precariousness to several factors: 1) Accelerating nuclear programs, which increased the likelihood of nuclear war; 2) climate change with record-high concentrations of greenhouse gases in 2020, one of the two warmest years on record; and 3) “continuing corruption of the information ecosphere on which democracy and public decision making depend.” This last factor, first identified as a primary danger by the Atomic Scientists in 2018, is now seen as a “threat multiplier,” as demonstrated by the unnecessary death and suffering from COVID-19 due to “false and misleading information disseminated over the Internet […] often driven by political figures and partisan media.”23 On the basis of those factors, the timekeepers considered advancing the clock even closer to midnight, except that they saw a positive counterbalance in the US rejoining the Paris Climate Accord under President Joe Biden, who supports science-based policy and international cooperation. With respect to their fear of the “misuse of information technology,” which demonstrates the “vulnerabilities of democracies to disinformation,” the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists has identified opportunities for resistance that are well-suited to artists’ use of media: “Leaders react when citizens insist they do so, and citizens around the world can use the power of the Internet to improve the long-term prospects of their children and grandchildren. They can insist on facts, and discount nonsense. They can demand action to reduce the existential threat of nuclear war and unchecked climate change. They can seize the opportunity to make a safer and saner world.”24

In the late 1990s artists began using the Internet as a medium for interventions that had real-world impact on governments and corporations. Such artists were hardly passive flâneurs, as described by Baudelaire and Benjamin. Rather, they deployed tactics much closer to the situationist concepts of dérive and détournement, becoming digital activists and online guerillas. Such forms of electronic civil disobedience include tactical media, hacktivism, and culture jamming.25 For example, in 1998 the Electronic Disturbance Theater’s (EDT) FloodNet program deployed a distributed denial of service (DDoS) attack to flood Mexican government websites until the overload crashed the servers. This work of hacktivism was a response to the Acteal Massacre in December 1997.26 The EDT project drew attention to the Zapatista cause and to the violent actions of the Mexican government against its people.

The artists collective ®TMark (pronounced artmark) was founded in the 1990s as an activist consulting firm. Around the turn of the century they carried out two successful campaigns: 1) defending the European artist group eToy from a court injunction filed by Internet toy vendor eToys over rights to the domain eToy.com; and 2) defending the journal Leonardo from a lawsuit filed by Leonardo Finance, a French company that was disgruntled because the magazine (founded in 1968) turned up higher in search engine results than its website. Amidst ®TMark’s culture-jamming strategies, eToys corporation’s stock-price plummeted and the case was dropped. The Leonardo strategy produced a plethora of protest websites, creating an even more competitive environment for search-engine results for Leonardo Finance, whose suit was dismissed by the court.

More recently, Berlin-based artists and technologists Julian Oliver, Gordan Savičić, and Danja Vasiliev wrote the Critical Engineering Manifesto, which asserts that a “Critical Engineer considers any technology depended upon to be both a challenge and a threat. The greater the dependence on a technology the greater the need to study and expose its inner workings, regardless of ownership or legal provision.”27 Oliver and Vasiliev’s artwork PRISM: The Beacon Frame (2013-14), reveals cellular telephone network vulnerabilities that have been exploited by government agencies to spy on people and speculates on the NSA’s network surveillance equipment known as Prism. The artwork impersonates local cellular service providers, so that “phones in the presence of [PRISM’s] tower will hop onto the rogue network […] believing it to be trustworthy.” Unwitting audience members whose phones have been hijacked by the artwork are sent SMS messages of a “troubling, humorous, and/or sardonic nature,” such as “Welcome to your new NSA partner network” or “Spying Reform 2014-A6 Embrace Our Transparency.”28

Image 4.

Prism: The Beacon Frame. Awaiting credits from The Critical Engineering Working Group (Julian Oliver and Danja Vasiliev).

Artists will continue to play a vital role in exploring alternative futures and creating working models that enable us to preview what is to come. They will also become more sophisticated in their strategic use of electronic media to protest governments, to subvert corporate malfeasance, to question and subvert surveillance, and to draw attention to the hidden vulnerabilities in widespread consumer technologies. Korea’s 2016 Candlelight Revolution involved a sustained series of twenty peaceful protests that drew as many as 2.3 million people at a time (roughly 4% of the population) and a total of 16 million, leading to president Park Geun-hye’s impeachment on corruption charges. With this model as a guide, if artists can deploy their skills to mobilize 4% of world citizens—roughly equivalent to the entire population of the United States—perhaps we can effectively protest and mitigate global warming.

Future artists will continue to use technology in metacritical ways that “pervert technological correctness;”29 that is to say: they will (mis)use technologies to undermine the corporate or governmental ideologies and agendas that underlie them. Following Noë, art will become an ever-stranger tool that increasingly turns technology in on itself, or even turns it against itself. Rather than we humans “being the ones spoken to” by it (to paraphrase Heidegger), we will force it to speak to itself and to us in ways that reveal how technology is deeply embedded in modes of perception, knowledge production, surveillance and policing, economics, and sociality. As Rita Raley notes, tactical media practices demonstrate that “critique and critical reflection are at their most powerful when they do not adopt a spectatorial position on the (putatively neutral) outside, when they do not merely sketch a surface, but rather penetrate the core of the system itself, intensifying identification so as to produce structural change.”30 The growing trend of transdisciplinary collaborative research at the nexus of science, engineering, art, and design (SEAD) will play a role in humanizing technology while, at the same time, generating breakthrough innovation. Such innovation will extend well beyond commercially viable products and will embody subtle, insidious, and profound shifts in perception and consciousness, reframing how knowledge is constructed and how we live our lives.

In addition, future artists will increasingly recognize the limits of technologies derived from scientific rationality and will seek to develop and deploy alternative technologies that are derived from other systems of knowledge. They will push beyond the limits of academic discourse and scientific rationalism. Following the models of Ascott and Oliveros, they will merge rational and super-rational forms of technology. What I have in mind here are forms of knowledge, modes of perception, and states of consciousness cultivated through meditation, yoga, shamanism, and other spiritual technologies. Art is closely allied with shamanism and healing in many cultural traditions, so in our struggle to overcome technological enframing why limit our arsenal to art, as ordained by Heidegger? Indeed, since the 1950s various esoteric traditions have had an important impact on contemporary aesthetics and arguably have great potential for transforming consciousness in ways that can turn back the hands of the Doomsday Clock. For the greatest challenges to protecting the planet from the catastrophic effects of global warming are not technological, they are attitudinal and volitional: the citizens and governments of the world must open our hearts and minds to the kinship of all beings and we must harness the empathy and willpower to recover from the cultural logic (and hydrofluorocarbons) of the Capitalocene-Chthulucene.

Ascott and Oliveros have joined art, science, and technology with various spiritual traditions to achieve expanded forms of consciousness.31 Through her intensive studies of Buddhism, meditation, t’ai chi, qigong, and karate, Oliveros developed a discipline and language of mind-body energetic flow and control. Like the techniques upon which she drew, her practice and pedagogy were designed to rebalance the body’s complex systems and thus promote health. Such balance and health at an individual level are perhaps a prerequisite to balance and health at the level of society. By 1970 Oliveros had begun writing the Sonic Meditations, which incorporated telepathy and astral projection. This landmark in contemporary music composition continues to inspire composers and performers nearly half a century later. As music critic John Rockwell observed: “On some level, music, sound, consciousness, and religion are all one, and she [Oliveros] would seem to be very close to that level.”32

Ascott’s praxis draws parallels between cybernetics and psi phenomena, telematics and telepathy, and virtual reality and expanded states of shamanic consciousness. At the same moment that Oliveros was writing the Sonic Meditations, Ascott’s 1970 essay “The Psibernetic Arch” drew parallels between “two apparently opposed spheres: cybernetics and parapsychology, the west and eastsides of the mind, so to speak; technology and telepathy; provision and prevision; cyb and psi.” Ascott further proposed that “art will become, and is perhaps already beginning to be the expression of a psibernetic culture in the fullest and most hopeful sense: the art of visual and structural alternatives.”33 Joining East and West, ancient Taoist oracle and silicon techno-futurism, Ascott’s Ten Wings (1982, part of Robert Adrian’s The World in 24 Hours) connected artists in sixteen cities on three continents via computer networking to facilitate the first planetary throwing of the I Ching.34 Ascott theorized the global field of consciousness that emerged in telematic art in terms of Teilhard de Chardin’s concept of the noosphere, Gregory Bateson’s notion of mind-at-large, and Peter Russell’s model of the global brain. In words that might as easily have come from Oliveros, Ascott proclaimed that telematics “constitutes a paradigm change in our culture and […] what may amount to a quantum leap in human consciousness.”35

Telepresence and telepathy are recurring themes in Oliveros’ work. The third Sonic Mediation, which consists of “Pacific Tell” and “Telepathic Improvisation,” is amplified by the fourth (untitled), which instructs groups of participants to perform either part of the third meditation while “attempting inter-group or interstellar telepathic transmission.” Oliveros’s projections on quantum listening and quantum improvisation from the late 1990s to the mid-2000s parallel Ascott’s musings on technoetics and photonics from the same period, both offering artistic visions for the future. In her 1999 essay “Quantum Improvisation” Oliveros lists the ideal attributes for a future artificial intelligence “chip” with which she could make music. They include the imaginable technical ability to calculate at speed and complexity beyond the human brain, as well as more abstract psychic abilities: “the ability to understand the relational wisdom that comprehends the nature of musical energy; the ability to perceive and comprehend the spiritual connection and interdependence of all beings and all creation as the basis and privilege of music making; the ability to create community and healing through music making; the ability to sound and perceive the far reaches of the universe much as whales sound and perceive the vastness of the oceans. This could set the stage for interdimensional galactic improvisations with yet unknown beings.”36

Oliveros’ praxis bears striking affinities with shamanic rituals, which have also influenced Ascott’s work. A shaman is a special individual, one who is partly self-selected and partly anointed by other shamans to play a unique role in a community. The shaman is at once revered and feared because of their powers, which can both cure and harm. Often a shaman proves their shamanic potential through a self-healing process in which failure would result in death. The shaman is both of this world and of the world beyond. The shaman communicates with spirits and ancestors in the beyond, learns from them, and brings that knowledge or wisdom back to this world in order to cure ill members of their community and to protect or heal the community as a whole. In “The Artist as Shaman” Burnham states that “it is precisely those artists involved in the most naked projections of their personalities who will contribute the most to society’s comprehension of its self.” For Burnham, the pathologies of society could be overcome only through revealing its “mythic structures” and unfolding its “metaprograms.” He saw art as a vehicle for such revelations and certain individual artists as the shamans whose neurotic incantations could liberate us from those metaprograms, for the shaman “magnifies every human gesture until it assumes archetypal or collective importance.”37

In the late 1990s, Ascott’s conception of art was dramatically impacted by his participation in shamanic rituals with Kuikuru payés in the Amazon and through his indoctrination into the Santo Daime community in Brazil. Ascott writes that the shaman “is the one who ‘cares’ for consciousness, for whom the navigation of consciousness for purposes of spiritual and physical wholeness is the subject and object of living.” In states of consciousness expanded through ancient ayahuasca rituals the shaman can “pass through many layers of reality, through different realities” and engage with “disembodied entities, avatars, and the phenomena of other worlds. He sees the world through different eyes, navigates the world with different bodies.”38 The shaman can embody the consciousness of other beings, including other animals, making them ideal leaders for enacting the sort of kinship theorized by Haraway.39 Oliveros performed some of these shamanic roles described by Burnham and Ascott. The “navigation of consciousness for purposes of spiritual and physical wholeness” was “the subject and object” of her personal and professional life. Her compositions develop strategies for focusing attention that enable performers and audience members to “pass through many layers of reality, through different realities.”

Image 5.

Jeong Han Kim, BirdMan’s Vertical Eye Tracking System, 2006-2008. Wearable perception device (MaxMAP/Jitter, three cameras, four servomotors, PIC-microcontroller), variable size. LMCC, New York, NY, U.S. & Seoul, Korea.

Korea has a rich tradition of shamanism that continues to inspire artists, including Jeong Han Kim. His multimedia art installation BirdMan (2014) explores the shamanic realm of hybridity between humans and nonhuman beings and asks probing questions about the nature of consciousness and healing: How do human beings conceptualize the world? Can the hybrid world of BirdMan transform perception beyond the limits of human physiology? If new perceptions create new metaphors, can the experience of another species’ perceptual reality help create hybrid perspectives, marked by greater empathy and ecological sensitivity? The concept of a hybrid bird-man appeared to Kim in a dream, in which he learned bird language from a monster with a bird head and only one wing. The dream and the artwork can be interpreted as an attempt to resolve the artist’s guilt over a traumatic experience in which his childhood fear of birds prevented him from helping a trampled and dying, one-winged bird. As Kim and his co-authors note, in Korean tradition “some shamans can share their own bodies with the deceased soul. Whenever a shaman is possessed by the spirit of the dead, s/he acts, speaks, and senses like another person, as if borrowing the perception of the deceased. This moment looks like a coexistent state of the living body and the dead in which perception and identity of the two is hybridised.”40

The Buddhist idea that “the ‘self ’ is not different from the ‘other’” is another prevailing concept in BirdMan. The work offers the audience an opportunity to experience a form of hybrid perception that joins human and avian qualia (the internal and subjective components of sense perceptions). In so doing it enables us to expand our consciousness beyond the limits of our embodied human minds by joining self and other, to create new identities in between humans and nonhumans, and as a result, to create new metaphors to live by and to live with.

Image 6.

Jeong Han Kim, BirdMan (The birth), 2006. Interactive installation (anatomical fossil sculpture, BirdMan eye system emulator, MaxMAP/Jitter, three cameras, four servomotors, PIC-microcontroller, three monitors), variable size. SAIC G2 Gallery, Chicago, IL., U.S.

Indeed, the pressing and enduring concerns of nuclear war, global warming, and the abuses of technology demand that we expand our perceptual domain. We must expand our methods of creating knowledge beyond scientific rationality. We must expand our means and channels of communication. Artists must summon the full power of poiesis, the possibilities of our “strange tools,” and the elusive “wisdom” to correct “a too purposive view of life.” We must embrace our kinship with all earthlings and “stay with the trouble.” As Kim observes: “Ecologically and creatively, humans are able to live depending on the meaning of events they create, not through human judgment but through perception as Other. We, as human beings, endlessly create our stories on the premise that there might be infinite ways to communicate with the others.”41 If we want to have a future, the artists of the future cannot be digital flâneurs, they will have to be highly engaged activists that amplify deviations and pervert technological correctness. They will have to be shamanic visionaries like Ascott, Kim, Oliveros, and Park, who commune with other forms of life and intelligence, who experience heightened forms of perception and create systemic metaphors, who preserve the dignity of all beings, and who can heal and preserve the Earth for posterity.