From a Book on Architecture to a Book of Pleasure: Caʿfer Efendi’s Risāle-i Miʿmāriyye, 1614

Reception date: March 24, 2023. Acceptance date: August 2, 2023. Date of modifications: August 15, 2023.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.25025/hart15.2023.05

Gül Kale

is trained as an architect (ITU) and architectural historian (McGill). Before joining Carleton University as an Assistant Professor of Architectural History and Theory, she was awarded a Getty/ ACLS postdoctoral fellowship in Art History in 2018-2019. Her areas of expertise are architectural history and theory with a focus on the early modern Ottoman empire, and cross-cultural and global histories and theories of material culture and of the built environment in the wider Mediterranean world and the Middle East. She is interested in architecture’s relationship to diverse forms of knowledge and sciences from an interdisciplinary perspective. Her book-length project is the first critical analysis of the only early modern book written by a scholar, Cafer Efendi on Ottoman architecture entitled "Risale-i Mimariyye (1614). Most recently, she has been awarded a SSHRC Insight Development Grant to develop her research on the social and cultural history of architectural tools and measurements.

Translated by: María Mercedes Andrade. Associate Professor, Universidad de los Andes, Colombia.

Abstract:

In conjunction with Mimar Sinan’s autobiographical memoirs, Ca’fer Efendi’s Risāle-i Mi'māriyye (Book on Architecture), penned around 1614, represents a unique primary source, not only within the Ottoman Empire but also in the broader Islamic world. Despite being one of the few texts authored by a scholar exploring the intricate interplay between architecture, diverse knowledge modalities, and artistic practices, the manifold implications and underlying aspirations of the Risāle, in terms of its connection to book cultures and writing traditions, remain inadequately comprehended. This article endeavors to shed light on specific sections from the Risāle, aiming to elucidate the ethical, social, and intellectual incentives that impelled a scholar like Ca’fer Efendi to undertake the writing of a book on architecture and the life of the chief architect, Mehmed Agha. To commence, we shall delve into the Risāle’s intended audience, considering the perspective of both its author, a member of the erudite class, and his patron, Mehmed Agha. Subsequently, we will probe how Ca’fer Efendi endeavored to underscore the architect’s and architecture’s social and ethical significance within his work, catering to his scholarly readership. This article will further explore the perception of architecture as a conduit for wisdom and knowledge, a rationale that elevated its standing within the hierarchy of sciences and ultimately facilitated a scholar’s authorship of a dedicated architectural book. Finally, we will delve into how an architectural publication transcended the realm of mere readerly pleasure, evolving into an integral component of Ottoman gift culture, thereby fostering the notion of architecture as a gift to society.

Keywords: Ca’fer Efendi, Ottoman Empire, Architecture, Ethical motivations, Gift culture.

De un libro de arquitectura a un libro de placer: Risāle-i Mi’māriyye de Ca’fer Efendi, 1614

Resumen

En conjunto con las memorias autobiográficas de Mimar Sinan, la Risāle-i Mi‘māriyye (Libro de arquitectura) de Ca‘fer Efendi, escrita alrededor de 1614, representa una fuente primaria única, no solo dentro del Imperio Otomano, sino también en el mundo islámico más amplio. A pesar de ser uno de los pocos textos escritos por un erudito que explora la intrincada interacción entre la arquitectura, diversas modalidades de conocimiento y prácticas artísticas, las múltiples implicaciones y aspiraciones subyacentes de la Risāle, en términos de su conexión con las culturas de los libros y las tradiciones de escritura, permanecen inadecuadamente comprendidas. Este artículo se esfuerza por arrojar luz sobre secciones específicas de la Risāle, con el objetivo de elucidar los incentivos éticos, sociales e intelectuales que impulsaron a un erudito como Ca‘fer Efendi a emprender la escritura de un libro sobre arquitectura y la vida del arquitecto principal, Mehmed Agha. Para comenzar, profundizaremos en la audiencia prevista de la Risāle, considerando la perspectiva tanto de su autor, un miembro de la clase erudita, como de su patrón, Mehmed Agha. Posteriormente, investigaremos cómo Ca’fer Efendi se esforzó por destacar la importancia social y ética del arquitecto y la arquitectura en su obra, atendiendo a su audiencia académica. Este artículo también explorará la percepción de la arquitectura como un conducto para la sabiduría y el conocimiento, una justificación que elevó su posición dentro de la jerarquía de las ciencias y, en última instancia, facilitó la autoría de un tratado arquitectónico dedicado por parte de un erudito. Finalmente, profundizaremos en cómo una publicación arquitectónica trascendió el ámbito del mero placer de lectura, convirtiéndose en un componente integral de la cultura de regalos otomana, fomentando así la noción de la arquitectura como un regalo para la sociedad.

Palabras clave:

Ca’fer Efendi, Imperio Otomano, Arquitectura, Motivaciones éticas, Cultura del regalo

De um livro de arquitetura a um livro de prazeres: El Risāle-i Mi'māriyye de Ca'fer Efendi, 1614

Resumo

Em conjunto com as memórias autobiográficas de Mimar Sinan, o Risāle-i Mi'mariyye de Ca'fer Efendi, escrito por volta de 1614, representa uma fonte primária única, não apenas no Império Otomano, mas também no mundo islâmico em geral. Apesar de ser um dos poucos textos escritos por um acadêmico para explorar a intrincada interação entre arquitetura, vários modos de conhecimento e práticas artísticas, as múltiplas implicações e aspirações subjacentes do Risāle, em termos de sua conexão com as culturas de livros e tradições de escrita, permanecem insuficientemente compreendidas. Este artigo procura esclarecer seções específicas do Risāle, com o objetivo de elucidar os incentivos éticos, sociais e intelectuais que levaram um estudioso como Ca'fer Efendi a escrever um livro sobre arquitetura e a vida do arquiteto-chefe, Mehmed Agha. Para começar, vamos nos aprofundar no público-alvo do Risāle, considerando a perspectiva tanto de seu autor, um membro da classe acadêmica, quanto de seu patrono, Mehmed Agha. Posteriormente, analisaremos como o Ca'fer Efendi procurou destacar a importância social e ética do arquiteto e da arquitetura em seu trabalho, atendendo ao seu público acadêmico. Este artigo também explorará a percepção da arquitetura como um canal de sabedoria e conhecimento, uma razão que elevou seu status na hierarquia das ciências e, por fim, facilitou a autoria de um tratado de arquitetura dedicado por um acadêmico. Por fim, vamos nos aprofundar em como uma publicação arquitetônica transcendeu o domínio do mero prazer da leitura, tornando-se um componente integral da cultura de presentes otomana, promovendo assim a noção de arquitetura como um presente para a sociedade.

Palavras-chave: Ca'fer Efendi, Império Otomano, Arquitetura, Motivações éticas, Cultura de presentes.

When Caʿfer Efendi (d. after 1633) completed the Risāle-i Miʿmāriyye (Book on Architecture) around 1614, in the final couplet of his closing poem, he called his book not only a Mimāriyye (Book on Architecture) but also a Safānāme (Book of Pleasure).[1] He expected his readers to take pleasure in reading about architecture and the life of the chief architect, Mehmed Agha (1606–1622?), his friend and benefactor. Accordingly, Caʿfer Efendi advised his friends to make copies and to enjoy reading from his book during their gatherings. He anticipated that Mehmed Agha’s followers and friends would read the Risāle and recall his various deeds and virtues. Thus, his book would be immortal in the hands of his readers, even if the buildings were to disappear over time. The earlier autobiographical memoirs of the renowned Ottoman chief architect Mimar Sinan (d. 1588) had projected a similar desire to present the book as a memento to his friends.[2] It is underlined in that text that when Sinan’s friends read of his efforts they will regard him with high esteem and remember him with blessings.[3]

In this article, I will discuss some selected sections from the Risāle to explore the ethical, social, and intellectual motivations that led a scholar like Caʿfer Efendi to write a book on architecture and the life of the chief architect Mehmed Agha. First, I will discuss the audience of the Risāle both according to its author, a member of the learned class, and his benefactor Mehmed Agha. Next, I will explore how Caʿfer sought to underline the social and ethical role of the architect and architecture in his book for his scholarly audience. The article will then examine the perception of architecture as a means for wisdom and knowledge, which justified its higher status within the hierarchy of sciences and eventually enabled a scholar to write a book on this specific topic. Finally, I will discuss how an architectural book was not only offered as a book of pleasure for the readers, but also became a part of the Ottoman gift culture, evoking the perception of architecture as a gift to society.

1. The Structure of the Risāle

Caʿfer Efendi starts his book by providing an index of the fifteen chapters with short explanations of their contents (Figure 1). Following this index he lists the ten odes (kaside) and four lyric poems (gazel)[4] in the book by mentioning their dedicatees. In the introduction he includes eulogies and poems addressed to God, the prophets, divine creation, Sultan Ahmed, and finally the architect Mehmed Agha. In his poems, as a concise example of his approach to the analogy between human creation and the cosmos, architectural metaphors are used to depict divine creation by assimilating the heavenly spheres to lofty domes or shining stars to ornamented candles. After these praises, he suggests focusing on the book’s central topic and begins by offering a brief list of the type of works built by Mehmed Agha including schools, bridges, and fountains, some of which were built through the chief architect’s patronage. He concludes his introduction with another index that describes his subject matter in further detail.

Caʿfer opens the first chapter by narrating the arrival of Mehmed Agha to Istanbul from Rum-ili (Balkans) in the year 1562 as a recruit (devshirme).[5] After six years of training and learning the Ottoman customs, Mehmed Agha became the guard of the garden of Sultan Süleyman’s tomb. Then, he finally entered the service of the imperial gardens, which was the beginning of his many adventures in Ottoman lands until he became the chief architect. Later, Caʿfer narrates how the life of the architect was shaped through his encounters with music, geometry, mother-of-pearl inlay, and architecture. The first chapter also names the ancient masters of stonemasonry and carpentry. In the second chapter, he describes how Mehmed Agha came to master his art and became a favorite of the sultans and viziers through fashioning exquisite works. By presenting his artworks as gifts to the sultans and the courtly elite, Mehmed Agha was promoted to be the gatekeeper of the Sublime Porte and then, by imperial decree, became the chief summoning officer of the four kadıs of Istanbul. The third chapter describes the many places the architect visited, including Anatolia, the Balkans, and the Crimea before being named water inspector (su nāzırı) in 1597, followed by his promotion as the chief architect (Mimārbaşı) of the Royal Corps of Architects in Istanbul in1606. The aim of the fourth chapter is to praise the architect’s good deeds and character based on the cardinal virtues, and the fifth chapter is an account of the restoration of the Kaʿba and the minbar (pulpit) of the sanctuary of Abraham. Caʿfer promises to give a list of the buildings built by Mehmed Agha, but several pages were left blank, probably to be completed later. In the sixth chapter, the present state and building process of the Sultan Ahmed Mosque, located on the Hippodrome in Istanbul, is conveyed by underlining the efforts of the chief architect Mehmed Agha under great stress. The following chapters also discuss a wide range of subjects, such as the science of measurement, the architect’s cubit, and the units of measurements used by architects; the terms used in architecture for building types in the three languages of Arabic, Persian, and Turkish; the materials used in buildings, again in three languages, as well as the tools used by stonemasons and carpenters, which are then compared to musical instruments based on their shared foundations in the science of geometry. After giving blessings for various eminent figures including Mimar Sinan and other chief architects, Caʿfer concludes his book by calling it a “Safānāme” (Book of Pleasure), before giving the year of completion, 1614, in numerical calculation (ebced hesabı).

2. The Risāle in Architectural Historiography

In his introduction, Caʿfer mentions earlier texts written for the previous chief architects, hoping to position his writings within the tradition of hagiographies (menākıbnāmes).[6] He was probably thinking about Mimar Sinan’s autobiographical memoirs, the only Ottoman texts on architecture written in the sixteenth century,[7] which Sinan dictated to his friend, the poet-painter Mustafa Sai Çelebi (d. 1595–96), shortly before his death. Mimar Sinan was Mehmed Agha’s mentor and, during their master-apprentice relationship, he served as a model for Mehmed Agha’s future deeds. Sinan’s texts also served as an example for Caʿfer when he set out to write about the life of Mehmed Agha. Considering there was no set tradition of writing books on architecture in the seventeenth-century Ottoman world, it is plausible that this was the most relevant literary model for Caʿfer’s endeavors.

Caʿfer must have read Sinan’s memoirs in detail. In his final chapter, he extends his blessings to “Koca Mimar Sinan Ağa” and not only gives a long record of Sinan’s works but also refers to the architect’s many military deeds.[8] Caʿfer’s list comprises the type and number of Sinan’s architectural works, which correspond closely to the specifics found in the latter’s memoirs. Although Caʿfer also mentions the other previous chief architects, Davud Agha (1588–98) and Dalgıç Ahmed Pasha (1598–1606), who preceded Mehmed Agha, Sinan is the only master cited along with a detailed list of his works. As mentioned, Caʿfer promises to include in his text a list of Mehmed Agha’s charitable works, such as Friday mosques, masjids, medreses, bathhouses, palaces, kiosks, bridges, and fountains.[9] He was probably trying to follow Sinan’s example of including such lists so that Mehmed Agha’s name could be commemorated along with his architectural deeds. However, the pages left blank for this list in the manuscript suggest that the task of compiling a list of Mehmed Agha’s buildings was not his priority.

Since Caʿfer writes that his topic is based on the life of the chief architect Mehmed Agha, the Risāle has been categorized as a book consisting mainly of Mehmed Agha’s accomplishments and Caʿfer’s exaggerated praises.[10] However, the Risāle’s content surpasses any one literary genre or scientific tradition; indeed, there is much more to the work than a list of Mehmed Agha’s deeds, and it is clear that his understanding of architectural knowledge far surpassed a mere list of buildings. The Risāle is a fusion of various forms of knowledge, ranging from dream narratives to mathematical sciences, and from musical theories to lyric poems. Consequently, not only do the forms of knowledge fuse, but the reader also witnesses the fusion of horizons from different personas, combined in the figure of the imperial chief architect—who was a gardener, musician, gatekeeper, military official, governor, artist of mother-of-pearl inlay, and water inspector.

Along with Mimar Sinan’s autobiographical memoirs, Caʿfer’s Risāle has been a unique primary source, not only in the Ottoman empire but also in the Islamic world in general. Mimar Sinan’s writings have been the subject of detailed studies.[11] Although it is one of the few texts written by a scholar on the relation between architecture, diverse modes of knowledge, and artistic practices, the Risāle’s manifold implications and aspirations have not been properly understood in architectural history.[12] Moreover, the scarcity of Ottoman books on architectural history and theory has prevented us from fully understanding the role of books in early modern times. Therefore, the study of the architecture’s theoretical bases and the relation between architectural thinking and making in the pre-modern Islamic world has become a problematic undertaking.

Despite the variety of knowledge contained in these two books, it has been generally assumed that there is no significant body of architectural texts from the Ottoman period. This assumption often went unchallenged by scholars, who claimed that architectural books before the nineteenth century were probably limited to instrumental sets of rules for architecture, as understood in the modern sense.[13] Historians, who took this conjecture for granted as a criterion for evaluating the few available Ottoman texts on architecture, fostered the reception of the Risāle as an incoherent work with no “factual” information. The search for “historical facts” led to the dismissal of its poems and narratives as peripheral subjects unrelated to architecture.[14] Thus, the Risāle’s place in global architectural history has not been properly understood.

It seems clear by now that, if we are to gain a better comprehension of the Risāle’s content and place within architectural history, the criteria by which it was previously judged must be reassessed. The genres of architectural writing have been far from homogenous and experienced considerable transformations throughout history. An appreciation of diverse epistemologies in architectural writing will allow us to read the Risāle with an openness that reveals diverse motivations and approaches inherent in the text. The Risāle must be read with a sensibility to its author’s wider intentions and its link to the mental worlds, perceptions, practices, and sensibilities of his milieu. Reading it in isolation from its literary, intellectual, scientific, artistic, and historical contexts, prevents one from grasping the underlying correlation between theoretical, poetic, and ethical concerns; narratives about artworks, ethical stories, mathematical discourses, poems, and cosmological accounts interconnect on varying levels in the Risāle. This seeming complexity caused by the union of various genres in one book begins to dissolve when we look closer to the meaning of the word “risāle,” which I translate as “book” rather than “treatise.” Such a choice stresses the richness of the Risāle’s content consisting of stories, historical accounts, rhetorical debates, ethical virtues, and poems along with mathematical theories. The etymological root of the word “risāle” indicates an oral message, which as it developed into written form retains a direction towards deeper inquiries.[15] This connection to oral cultures invested the risāle with an interpretive and innovative aspect, since most unconventional ideas originated from such works, which did not fit into a certain genre or canonical writing. Thus, the use of the word “book” suggests a wider framework that encompasses various modes of knowledge, based on both oral and literary cultures, which are precisely the origins of Caʿfer Efendi’s various narratives and considerations.

3. The Risāle’s Audience: Architects, Apprentices, Scholars, Students, and Patrons

Tracing back the Risāle’s audience throughout history has been a challenging task, because there is only one extant seventeenth-century manuscript copy of the book, to be found in the Topkapı Sarayı Museum Library, cataloged as Yeni Yazma, n. 339 (Figure 2). It is a narrow codex bound in brown leather that measures 415 mm by 150 mm and consists of eighty-seven numbered and four unnumbered folios of unwatermarked Turkish paper. The complete manuscript was written by the same hand and the taʿliq script was written in black ink, while red ink was used in chapter headings, some marginal notes, verses, and hadiths, which indicate the work of a well-versed scholar. Marginal notes, which include corrections and additions to the text, and blank pages reveal that this was Caʿfer’s autograph manuscript. The Topkapı manuscript has an inscription naming the book’s previous owner, on the first numbered folio, which contains a list of the poems. Rather than being part of an endowed library, the book was in the private possession of one Mahmud ibn Hüseyin.[16] In the early twentieth century, the book entered the Imperial Treasury of the Topkapı Palace, although its previous whereabouts are unknown as there are no markings or dates on the manuscript. Furthermore, it is not possible to know how extensively Caʿfer’s book circulated among the Ottoman literati and how many times his friends copied it, as Caʿfer expected them to.[17] Yet, the subject of his chapters, his social entourage, and his personal references indicate that there were several target audiences for Caʿfer’s writings.

While Caʿfer’s book had no exact literary precedent, his manner of writing and language stem from the literary traditions of Ottoman learned groups, which he was exposed to during his higher education, as is also suggested by his title, “Efendi.”[18] Rather than being merely a practical guide for a group of artisans in the craft guilds, his incorporation of commonly shared ethical stories, theological verses, and sayings, mythical accounts, lyric poems, esoteric and exoteric knowledge, linguistic evaluations, along with mathematical theory, make his subject more accessible and appealing to various groups. This suggests that he was writing for a wider audience. Caʿfer’s social circle, consisting of high- and mid-ranking officials, medrese scholars, and followers of the Sufi orders, was probably his main audience. Most members of these groups would recognize his sources and references due to their similar educational and social backgrounds as well as shared cultural interests.

Caʿfer befriended members of Sufi orders and madrasa students, who visited and conversed with him in his lodgings. On one important occasion, his friends learned that he was writing a book on architecture based on the life of the chief architect Mehmed Agha and gathered at Caʿfer’s door to share their own stories about Mehmed Agha’s generosity as their constant supporter.[19] After this, Caʿfer specifically included an ethical story by Abu Hanifa (d. 767), the founder of the Hanafi school (one of the four Sunni schools of Islamic jurisprudence followed extensively by the Ottomans), about the importance of writing a book for one’s livelihood, a topic that would be of interest to madrasa scholars and students. On the other hand, his account simultaneously promoted his own book as one worthy of being copied by them.[20] Furthermore, officials such as the revenue collectors and waqf administrators of properties are mentioned in the tenth chapter.[21] He must have expected scholars and practitioners who acted as officials during architectural, cadastral, or topographical surveys to benefit from his chapters on the science of surveying and units of measure. The role of the architect’s cubit in the law of inheritance was of interest to jurists and state officials, who valued this theological justification and its mathematical foundations.[22] Caʿfer advised his learned audience to trace his references to well-known books on the laws of inheritance, geometry, and arithmetic if they wanted to deepen their understanding of the more complex subjects related to these sciences.[23]

Despite these scholarly priorities, Caʿfer thought that his book was equally

relevant to various practitioners. Although he privileged terminological

definitions of words, his frequent comparisons to common meanings used by

architects and surveyors in everyday language underscore his desire to address

practitioners along with scholars and officials. This is not an arbitrary

emphasis, since the use of proper language together with mathematical knowledge

was vital for officials and architects alike, who communicated and collaborated

during social affairs. One essential target group of practitioners consisted of

the guild of architects under the command of his benefactor, Mehmed Agha, where

stories pertaining to their patron saints and the noble foundations of arts and

architecture, similar to those found in the Risāle, would have been

orally handed down to future generations.[24]

As a mentor, Mehmed Agha must have considered the stories in the Risāle

as an important means to transmit his knowledge to his assistants and

apprentices, whose future accomplishments depended upon the attainment of

proper knowledge about the foundations of architecture. By retelling Mehmed

Agha’s memoirs Caʿfer was in

fact summarizing his own dialogues with the architect while writing the Risāle.

Mehmed Agha most likely recounted to him what his own master had taught him

(orally), and what he was, at the time, retelling to his apprentices during

their training. They must have covered various subjects, ranging from the

legendary tales of the patron saints (selected from the prophets and

philosophers) to the ethical virtues, along with the importance of geometry. Caʿfer was probably able to also visit Mehmed

Agha in the workshops, where the chief architect was instructing his

apprentices.

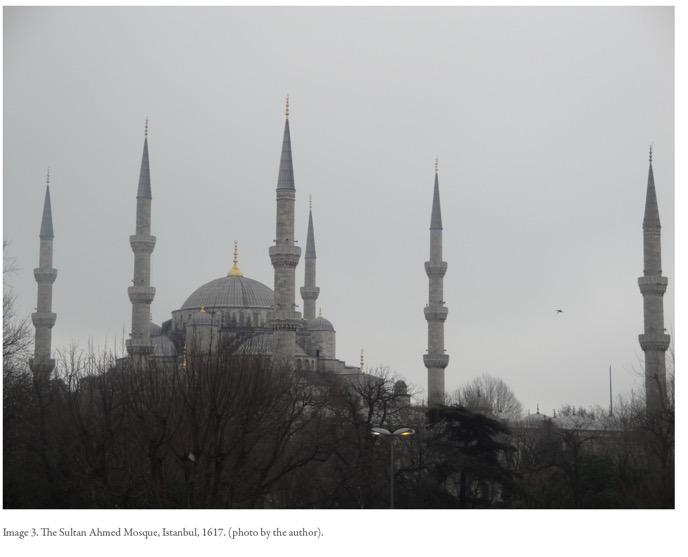

Moreover, Mehmed Agha’s close contact with the ruling circles suggests that there would have been another expected audience that appreciated architectural works as a meaningful part of their cultural world and would like to learn about its noble origins. Thus, Mehmed Agha had a broader readership in mind while relating his anecdotes to Caʿfer, ranging from the ruling elite—his patrons—to his future successor as chief architect. For example, Caʿfer’s section on the architect’s cubit, which was carried by the chief architect as a sign of his skill in architecture and geometry, served to elevate the status of the architect in the eyes of administrators and governors, who were concerned with State order.[25] Caʿfer recited many odes to the chief architect Mehmed Agha, who was a member of the military and acted as an administrator and governor at various points in his life.[26] He must have also composed poems for high-ranking officials like the grand vizier, Murad Pasha (d. 1611), most likely through the intermediary of Mehmed Agha who had close relations with the vizier.[27] By incorporating his poems for Mehmed Agha, Murad Pasha, and Sultan Ahmed I (r. 1603–1617) into his book on architecture, Caʿfer aimed to reach a wider audience; hence his search for personal relationships (intisāb) extend to courtly circles at a time when the Sultan Ahmed Mosque’s ongoing construction generated a renewed interest in imperial architectural projects (Figure 3).

4. Architecture as a Noble Subject for a Book

In spite of Caʿfer’s close contacts with the chief architect and the patrons of architecture, his main motivations in composing the Risāle relate to the scholarly appreciation and awareness of the contributions of architecture to the social order and prosperity, in addition to its spiritual dimension. Hence, his choice of architecture as a topic indicates that he considered it scholarly and noble enough to appeal to his wide audience and present him as a prominent scholar knowledgeable about a variety of subjects and sciences—for example, Caʿfer’s interest in exploring the etymological origins of words derives from his knowledge of linguistics. But it also reveals what a learned person like Caʿfer understood to be the role of architecture and the primary duty of an architect. First, he writes that in Persian lands some nomadic groups wandered in the mountains and dug holes on the ground in place of a home, which was called günc-şenc.[28] He then adds that for this reason mimar (architect) was called the joy-giver (șenledici) in ancient Turkish.[29] Significantly, he links the origin of architecture to making a place joyful by digging caves on the surface of the Earth, as homes. The old Turkish word for architect refers to a person who makes a place joyful by building temporary homes while wandering. This shows how cultivating a place to dwell, even for a short period, was seen as inseparable from the notion of giving joy to people. Caʿfer, however, notes that the word “joy-giver” was no longer used in his own time, now replaced by the word “mamur edici” (one who cultivates). Still, the words umrān and şenletmek point back to that original meaning, as in “to cultivate” and “to make prosperous.”[30] The Turkish word “mimar” shares the same Arabic roots with the word “imar,” meaning cultivation or making a place prosperous through human settlement.[31] This common meaning indicates that architecture was understood as an art carrying the potential to transmute a place from a deserted land into a joyful place. Similarly, in Mimar Sinan’s memoirs, the foundation of architecture is based on people’s aspiration to cultivate places:

It is obvious and proven to men of intelligence and wisdom and persons of understanding and vision that building with water and clay being an auspicious art, the children of Adam felt an aversion to mountains and caves and from the beginning were inclined towards the cultivation [tamir] of cities and villages. And because human beings are by nature civilized [medeniyyü’t-tab], they made day-by-day many types of buildings and refinement [nezāket] increased. [32]

According to Sinan’s narrative, after people gathered in mountains and caves they started to share communal life. They thus desired to prosper and refine their environments, which probably shifted the implications of the word “architect (mimar)” from establishing temporary dwellings towards building sedentary environments. Sinan’s memoirs note that human nature was inclined to civilization and thus to the formation of communities.[33] This mentality can be deduced from the writings of Ottoman scholars like Talikizade, the court historian, who stated in 1593–94 that one of the main qualities of the Ottoman dynasty, one that legitimized its ruling, was “the prosperity of lands and the riches of subjects in their imperial domains,” because it indicated “a fertile country with uninterrupted prosperous lands and an abundance of pious foundation.”[34] For Talikizade, continuously developed urban areas connected with travel roads and caravanserais were the most obvious sign of this prosperity. Although he writes as a State official, from the perspective of the ruler, many Ottoman scholars including Caʿfer must have shared Talikizade’s understanding of prosperity as one of the main goals of architecture.[35]

The Ottomans recognized that one of the first conditions to cultivate a wasteland was to build canals and wells to bring water to the population.[36] Mimar Sinan’s narratives about finding sources of water for canals and fountains reveal that nourishing lands and giving joy to people through waterworks were perceived to be a crucial part of the architect’s duties. The Ottoman scholar and poet Eyyûbi’s text on Süleyman’s deeds presents water as the source of life and prosperity, sharing the same sentiment.[37] He dedicated a long section to Süleyman’s building endeavors in water infrastructure, in addition to the building of Friday mosques.[38] Thus, fountains and wells would give joy to people and refine their surroundings as much as any monumental building. In Sinan’s memoirs, civic works are said to reinforce the imperial image and thus justify the ruler’s justice (adalet). Eyyûbi writes that the root meanings of the word “justice” implied virtuousness (ināyet), kindness (lutf), and generosity (ihsan) of the ruler towards the people (reaya).[39] Therefore, according to scholars, the word “cultivation (imar)” did not only refer to making monumental buildings; it meant creating a prosperous life and thus required fertile places, thoroughly integrated qualities that the Ottomans perceived as essential to psychosomatic health.

Nevertheless, together with long sections on the waterworks commissioned by Süleyman, the sultanic mosques and monumental buildings still occupy a privileged place in Mimar Sinan’s memoirs,[40] which indeed point to the example of Hagia Sophia to demonstrate that each civilization desired to leave behind monuments as signs of cultural refinement.[41] Sinan stresses that all of his buildings came into existence through the “lofty patronage” of the Ottoman dynasty, which meant that his buildings were the memorials (yādigār) of the ruling elite. [42] The dominant Hanafi law, harmonized with sultanic law, was codified by the shaykh al-Islam Ebussuud Efendi (1545-1574) and privileged the building of masjids and Friday mosques in the mid-sixteenth century. As Gülru Necipoğlu notes, this tendency led to the flourishing of mosques in the Ottoman Empire and reinforced congregational prayers as the visible signs of sovereignty.[43] The legitimacy of the ruler as a spiritual leader also justified the legitimacy of the Friday mosques.[44] While cities were prospering, main architectural deeds included the transformation of wastelands into agricultural areas for pragmatic or economic reasons, and the production of monumental buildings as symbols of religious and political power, such as the Süleymaniye Mosque.

In his longest memoir, entitled “Record of the Construction,” Sinan’s achievements are narrated mostly according to his patrons’ reactions in the courtly circles.[45] Such an insider’s view of how architectural works were undertaken through daily negotiation with court officials is not found in Caʿfer’s Risāle. Even though Caʿfer was writing his book while the Sultan Ahmed Mosque was under construction, even in the section specifically devoted to that building he mostly addresses the perceptions and concerns of his fellow scholars and Sufi groups. In his historical account of the rhetorical debates regarding the Kaʿba’s renovation, Caʿfer conveys the theoretical underpinnings of scholarly discussions without any detailed narrative of contemporary debates at the court. This again shows that he, from a scholarly perspective, perceived the role of the architect and the significance of architecture based on their social contributions, while promoting these aspects in his book for a broader audience outside the courtly circles. These readers would be concerned with just government, corruption among high officials, and the prosperity of the lands. It is interesting that opposition to the construction of the mosque was voiced for the most part in foreign travel accounts, while the Ottoman historians often referred to the mosque with praise.[46] This discrepancy in written accounts might relate to the divergencies between the partial observations of foreign visitors and widely held favorable opinion regarding the mosque on the part of the public. Whereas the former mainly drew information from their informers in correspondence with court and State officials, the latter’s reactions were based on lived experiences of the mosque complex.

Moreover, Caʿfer decided to unveil Mehmed Agha’s virtues and pious works, although charitable works were preferably to be kept secret according to tradition. While cautious of the limits of his revelations due to the secrecy between friends, Caʿfer’s reasoned choices demonstrate what he deemed important for his audience to know regarding the ethical conduct of a chief architect. In the fourth chapter, his main subject is Mehmed Agha’s generosity, one of the four cardinal virtues in Ottoman ethics literature.[47] After emphasizing his skill and courage, which earned him prominent positions, Caʿfer tries to show how Mehmed Agha’s kindness and generosity enabled him to devote all his fortune to good deeds. It was crucial for Caʿfer to justify his eulogies by highlighting the virtues that would have been most valued by his learned readers. The basis for calling someone virtuous (faziletli) was the acquisition of such virtues in real life.

Caʿfer divides the chief architect’s virtues into five categories. The first is his humility and benevolence towards the poor. He notes that even if someone gave a green leaf to Mehmed Agha, he would return it with various favors without hiding any of his wealth.[48] In the prologue, Caʿfer stresses that Mehmed Agha built many mosques, schools, fountains, hospices, and soup kitchens, some with his own fortune. This is important to disclose how the architect himself was a patron of architecture, rather than merely serving clients. An inscription from a fountain dating to 1604, which has not survived, mentions Mehmed Agha and describes it as the architect’s fountain (Mimar Ağa Çeşmesi).[49] For a scholar like Caʿfer, the practice of sponsoring public buildings distinguished the chief architect considerably from any other craftsman. Caʿfer then underscores the ever-open door of the architect’s house to those in need, like a soup kitchen,.[50] and mentions the generous support provided to poor students in search of patronage, a remark that prompts an account of Mehmed Agha’s constant support to his own cause in the following section. Mehmed Agha’s friendship and compassion enabled scholars like Caʿfer to continue their learning in Istanbul.[51] Nonetheless, as Caʿfer explains in the fourth section, Mehmed Agha was free from pride despite all his virtues; hence he always searched for guidance and knowledge from scholars, shaykhs, and viziers to improve his virtues by contemplating their skills and kindness.[52]

Caʿfer’s interest on ethical conduct gains new significance through his account of Mehmed Agha’s renovation work for the Kaʿba in the next chapter. He describes the artworks made by Mehmed Agha for the Kaʿba in Mecca and the Tomb of Muhammad in Medina. As he recounts in the index, his third lyric poem explains how these works earned the chief architect the title of “Architect of the Servant of the Two Holy Cities” (mimar-ı hādimü’l-Haremeyn).[53] Caʿfer writes:

By creating those beautiful works in the Kaʿba and the Tomb,

Your name became the Architect of the Servitor of the Two Holy Cities.

Those pure works for the magnificent State will pour back to you.

Your pure faith caused you to be right for that.

Your endless pious deeds have captivated the world.

Your fresh new works have radiated brightness like the sun.

Both the Revered Kaʿba and the Sacred Tomb,

With their closeness, became the beloved of your heart.

Your edifices generated great knowledge.

Without conquering them, Mecca and Medina became your cities.

Your kindness made the people, like Caʿfer, your servants.

With your heartfelt well-wishers, your devotees prospered.[54]

According to Caʿfer, Mehmed Agha derived much pleasure and honor from his involvement in these sacred works. He links Mehmed Agha’s accomplishments to his piousness. Although some scholars opposed the renovations, Caʿfer was convinced that Mehmed Agha’s virtues contributed to their successful completion.[55] He writes that the desire of all the chief architects would have been to be of service to these two sacred spaces in Mecca and Medina. Thus, the purity of Mehmed Agha’s hand—associated with his skill—, his piousness and generosity gained him this title. His artworks, contributing to the dignity of the sacred house and enhancing its significance for the people, implied eternal prosperity for the architect and the acquisition of spiritual knowledge for all.

Caʿfer’s comments on Mehmed Agha’s virtues and deeds culminate in the sixth chapter, where he turns to the Sultan Ahmed Mosque, one of his most burdensome yet important works. The Sultan Ahmed complex was planned to involve not only the mosque but also public buildings such as schools, a hospice, a soup kitchen, a covered market, gardens, and fountains intended to enhance the urban realm. Despite the difficulties inherent to the project, Mehmed Agha’s various skills and virtues provided Caʿfer with the assurance that the project would be completed. Caʿfer’s writings attempt to justify the chief architect’s efforts in the eyes of his fellow friends and high officials, who were anxiously waiting for the placement of the keystone for the dome.[56] The foundations were excavated through the prayers of the famous shaykh Mahmud Hüdayi and Evliya Efendi while Ahmed I carried soil to the foundations with his own hands in order to gain divine grace.[57] The many devotional prayers and sacrifices by the viziers, ulema, and shaykhs together with the sultan, and the efforts of many janissary groups during the foundation ceremonies, suggest the widespread interest in the mosque by many groups, who would also have worried about the chief architect’s skill, righteousness, and ability to complete this important imperial project.[58] In attempting to emphasize his close friend’s virtues and hard work, Caʿfer reiterates the main connotations of the word “mimar.” His writings divulge the very skills, virtues, and roles expected of him, in the service of promoting order in the early modern Ottoman world.

5. Preserving Architectural Knowledge in Writing

Although the social significance of architecture was well established by the time Caʿfer was writing his book, his effort to codify and elaborate on its ethical foundations through an architectural text was certainly unique. This ethical dimension of the book must have also related to a general sense of anxiety about the potential loss of architectural knowledge that was not written down in books. Mehmed Agha was one of the last chief architects who served for life. The Ottoman historian Naima writes that, although it was a lifetime position until the year 1644, Kasım Agha was removed from office. [59] While it cannot be easily evaluated as a sign of corruption in the system of the corps of architects, certain changes must have been already underway that would cause doubts regarding the transmission of architectural knowledge. In artistic traditions, this oral knowledge had to be transmitted to the right disciples to assure the endurance of the chain of knowledge. As Mimar Sinan wrote in his memoirs:

[And thus, in auspicious times, with] much courage and in blessed moments, with countless ideas and geometry [fikr ü hendese] (lives were consumed and with a thousand bitter tears, with striking and beating), auspicious madrasas and exalted hospices were designed. And in order that a memorial and record [of them] endure through the pages of time, a blessed index, a preface, eleven [chapters listing building] types, and an epilogue were prepared . . . It was given the name “A Book on Architecture” [Risāletü’l-Mi’māriyye].[60]

Against the decadence of the built world, Sinan’s memoirs suggested that books could withstand the ravages of time by conveying the knowledge of the ancestors to the next generations.[61] The perception that buildings were not immune to change is also palpable in Caʿfer’s closing poem:

Inscriptions are many on the gates of palaces.

The black specks [inscriptions] on them defile that gold for no reason.

How much we [try] to cultivate this world!

Is this transitory, ruined abode everlasting for anyone?[62]

While buildings exemplified the accomplishments of their builders and the past, Caʿfer emphasizes the transitory nature of the world, despite people’s attempts to immortalize their names through inscriptions. Thus, rather than valuing buildings merely as bearers of the names of those who built them, he underlines the ancient knowledge embodied in the buildings and the importance of preserving that knowledge through books. The underlying assumption for Caʿfer is that the many forms of ancient knowledge enshrined in architecture, such as geometry, music, and arithmetic, justified writing a book on this subject: this would then be the book’s primary purpose, and not a desire to make the patron’s names eternal or to communicate instrumental principles.[63]

Caʿfer indeed mentions the codification of the sciences of arithmetic and geometry in books as another motivation for preserving architectural knowledge in writing. When Mehmed Agha encountered the guild of the architects at the Topkapı Palace Gardens in Istanbul, he came across a young fellow reading a geometry book in the workshop of the artisans of mother-of-pearl inlay (sadefkārîler kārhānesi). Seeing Mehmed Agha’s interest, this fellow said: “If this boy turns toward this art with this talent, let me also teach him the science of geometry, and inscribe and present him with a copy of the book in my hand so that as long as he lives he will have in his hands a token (yādigār) from me.”[64] Many medrese graduates were known to write and produce manuscript copies of their books as their livelihood. On other occasions, they produced manuscript copies of other books as offerings to their colleagues based on their specific interests. Likewise, Mehmed Agha acquired a copy of a book on geometry from this knowledgeable master who was instructing scholars and practitioners in basic mathematical knowledge at the workshop. This story regarding the presentation of a book on geometry as a gift to support Mehmed Agha’s interest in architecture closely aligns with Caʿfer’s emphasis on the importance of books to transmit and preserve knowledge.

Caʿfer’s concern for the important role of writing in knowledge production becomes evident when he narrates how masters in the guild of architects explained the foundations of their art. The first patron saints (pirler) of stonemasons were recognized as the prophets Seth and Abraham, and the patron saint of the carpenters was Noah. Caʿfer incorporates a poem into his narrative:

If you wish to know your master, these good works are path to you

If you ask who our master is, he is the builder of the ancient house

Your recognition will embrace Abraham and Seth and Adam

O devoted brave man, then salute them all.[65]

Here Caʿfer may have chosen to integrate the poem into his writing in order to reinforce the impact of the story, but in all likelihood similar poems were primarily conveyed orally to the apprentices as an influential means of transmitting lessons. Their mythological connotations would be engraved in their memories in the form of rhythmic modes. Moreover, considering that Caʿfer is writing his book for a group of learned friends, as well as for Mehmed Agha’s circle, he must also have thought that his couplets would be reread in their gatherings for the oral transmission of architectural knowledge. Caʿfer conveys that the apprentices first learned about the patron saints of the masters, who were experts on stone buildings (kārgir), such as the noble sanctuaries and beautiful mosques.[66] The origin of architecture is found in the story of the building of the Kaʿba, which was considered the first house built on Earth by the prophets.[67] Based on legendary stories, masters were chosen from the prophets. This is indeed similar to the futuwwa tradition in guilds, where the admission ritual includes welcoming the members and assigning each one their “place according to rank” followed by “the sohbet, a period of social intercourse and chats with recitations from the Qur’an, the stories of prophets and saints and pirs.”[68] Likewise, the deeds of legendary figures were transmitted as models for the architects to follow in their own endeavors.[69] The son of Adam, the prophet Seth, also known as Hibetullah, was the patron saint of the architects.[70] Caʿfer notes that, according to the chronology given by Ibn Abbas, the renowned theologian, it had been 5679 years since Seth built the Kaʿba. After the flood, the prophet Abraham rebuilt it. Therefore, the first patron saints of stonemasons were Seth and Abraham, and the patron saint of the carpenters was Noah. Although the chain of masters had a long tradition in the guilds, in the early seventeenth century the established genealogies had become a generalized source of legitimacy. The late sixteenth century witnessed an abundance of genealogies, some of which traced the lineage of the Ottoman dynasty back to the time of Adam. These illuminated books, accompanied by mythical stories, were meant to be read to the sultans at gatherings.[71] Prophets were recognized as the bearers of divine knowledge through direct revelation. This wisdom engendered the first house on Earth, namely the Kaʿba built by Adam and Seth, which became a gathering place and a pilgrimage site. In Caʿfer’s words, the masters in the corps of architects first legitimized the importance of architecture through these sacred origins and lineage. The search for a lineage leading back to the first prophets, rather than to figures from Islamic history, might relate to the fact that the corps of architects also included many non-Muslims, such as Greek and Armenian masters.[72]

After this, Caʿfer associates the compilation of the first mathematical books with the building of the first sanctuaries, the Kaʿba and the Temple of Solomon, by prophets and philosophers. In his chapter on the renovation of the Kaʿba, Caʿfer claims that it was built forty years before the Temple of Solomon.[73] These sanctuaries were grounded in the ancient sciences of the sages, which verified the divine nature of knowledge embodied in them. After Adam, the first person to write, organize, and compile the science of arithmetic (ilm-i hesāb) and the science of astronomy (ilm-i nücūm) was the prophet Idris, associated with Enoch and Hermes. Idris was the first person to learn writing and explore the sciences of arithmetic and astrology. He was commonly thought to have acquired these sciences directly from God in order to transmit them through oral communication. As Caʿfer underlines, while students learned and memorized the sciences of geometry and arithmetic orally, Pythagoras compiled them into books. Caʿfer connects these stories to the building of the Temple of Solomon by claiming that Pythagoras wrote the books on these sciences at the time of David and Solomon, who was recognized for acquiring divine power.[74] Writing a book on the science of geometry, which was embedded in sacred buildings, assured the preservation of knowledge through time. In the same sense, Caʿfer’s emphasis on preserving architectural knowledge in books shows his interest in protecting the knowledge embedded in the building under construction, in both artistic and scientific traditions.

6. The Fusion of Oral and Written Traditions of Architectural Knowledge

As a scholar, Caʿfer conveys what he heard from Mehmed Agha and includes his own interpretations based on written sources. The reference to both the learned (ulema) and the architects as those most in need of geometrical knowledge not only indicates his desire to engage a wider audience but also his ability to draw from diverse modes of knowledge and sources. For example, although he transmits the master’s words as a part of oral traditions in the guild of the architects, Caʿfer also quotes from historical books such as the famous historian Şükrullah’s Behcetü’t-Tevarih and the account of Ibn al-Abbas, who was famous for his book of exegesis.[75] His Arabic, Persian, and Turkish definitions derived from famous dictionaries underscore that his intended audience included a broader stratum of Ottoman society, including learned groups and high- and mid-ranking officials interested and employed in architectural works. The lexicons that were highly esteemed by these groups provided the most authoritative sources for architectural terms listed in his book. The officials would be conversant with many terms that he included in his trilingual dictionary (Figure 4) and would use them in State affairs and records. Whereas Arabic was the language of the scholars, most of the apprentices and masters in the corps of architects, who had various ethnic origins, such as Turkish, Greek, and Armenian, in addition to novice boys coming from the Balkans, would have used Turkish as their daily language.[76] Mehmed Agha, a devshirme recruit form the Balkans, did not speak Arabic; during his military and administrative duties in Arab-speaking lands, he consulted his translator (tercemān).[77] This also explains why his definition of geometry (hendese) is first given in Arabic, followed by a Turkish translation.[78] We know that Caʿfer frequently consulted books on geometry in Arabic.[79] Considering books as the most authoritative sources of knowledge, the scholar Caʿfer probably quoted from a mathematical book written in Arabic, rather than drawing his statements directly from oral communications between the architects.

Thus, it is crucial to distinguish between Caʿfer’s erudite explorations based on written sources and the oral transmission of artistic knowledge such as practical geometry, which was taught in the corps of architects through apprenticeship. Yet, rather than a dichotomy, this condition underlines a desire to combine both modes of knowledge as valid sources for architecture. Caʿfer’s incorporation of quotations from history books, dictionaries, and books on mathematics—probably from his readings, as if transmitted by the masters—underlines how he aligned Mehmed Agha’s memoirs with his scholarly concerns.[80] This tendency emphasizes a scholar’s desire to base architectural knowledge on well-established written sources, although with an awareness of the necessity for the oral transmission of knowledge among architects. Caʿfer’s effort signals a critical moment in Ottoman architectural history when we witness the emergence of a conscious attempt to promulgate a literary tradition of architecture, which would be shared and appreciated by all learned groups, based on the previous writings of established scholars and the venerable sciences of geometry and arithmetic.

7. Narrating Architecture as a Source of Wisdom

In his closing poem, Caʿfer notes that the transmission of knowledge is a delicate matter and that it must be entrusted to the right disciple, who will understand and appreciate its value:

This book was betrothed to His Excellency the Aga.

Given that this (book) was (like) a youthful maid.

Let us guard it from the eye of the stranger,

Lest this pure gem falls into improper hands.[81]

Caʿfer thus likens his book to a maiden resembling a pure gem, who had to be kept away from the eyes of strangers. The revelation of knowledge to those who are qualified, who could understand its hidden meaning and use it for good, was a widely shared notion among the Ottomans. In one of the few Ottoman books on calligraphy, probably written between 1495 and 1543, Hâfızâde warns calligraphers not to pass on his book—also likened to a gem—to the hands of the ignorant and the ascetic due to the sacred knowledge conveyed in it. Yet, in the same vein, he condemns anyone who would hide it from the qualified ones.[82] But why did Caʿfer liken the architectural knowledge conveyed in his book to a precious gem that had to be protected?

In his chapter on the Sultan Ahmed Mosque, before introducing his Spring Poem, written as an eulogy to the mosque under construction, Caʿfer advises his audience to read his ode in order to grasp “on what kind of marvelous forms [eşkāl-i acībe] and curious attributes [ahvāl-ı garibe], this uplifting station [makām-ı dilküşā] and relaxing abode [mekān-ı ferāh-fezā] is embodied [vaz’ olunmuş].” [83] His qualifications for architecture recall the widespread understanding of the cosmos as a place of marvelous creations. The word “acā’ib” (marvelous) was often used to signify God’s creation and hence the importance of contemplating these symbols was frequently emphasized in written traditions.[84] This visual contemplation of the world aimed to acquire signs from its marvelous appearances in order to evoke astonishment at creation on the part of the viewer. In one of his poems, Hüdayi wrote: “Open your eyes and look to perceive lessons / This world is nothing but a place for contemplation.” [85] Thus, as Hüdayi highlighted, the world was perceived as a “location for contemplation” (temaşa-gāh) to grasp the various lessons (ibret) that were discernible in the universe. Ottoman authors used the word temaşa for the act of scrutinizing the universe and the natural world. Hüdayi’s poem is indicative of the common understanding of the importance of contemplating creation, particularly for the Ottoman Sufi circles in the early seventeenth century. Hüdayi’s writings on creation were in line with the texts on “Islamic cosmology” that depended upon “early collections of hadith on creation, cosmos, and natural phenomena.” [86] In these texts, the cognitive acts of “looking around” and “looking up” were “driven by contemplative or philosophical reasoning, ‘tafakkur,’ and they complemented one another.” [87] There was an ongoing interest in cosmography and the contemplation of the marvels of the world in the seventeenth century.

However, while mystically inclined writers stressed the importance of contemplating the wonders of creation, the marvels were not limited to natural phenomena, as Caʿfer also implies. Along with strange creations of the world, the legendary accounts of ancient buildings like the pyramids and the marvelous features of cities were explored in many cosmological-geographical works. Al-Ḳazwīnī’s (d. 1283) famous work was divided into two parts: ʿAd̲j̲āʾib al-Mak̲h̲lūḳāt, “The Marvels of Creation,” and Āt̲h̲ār al-Buldān , “The Monuments.” [88] Hence, “ʿad̲j̲āʾib i” (marvelous) was used for natural phenomena as well as for artifice in some Islamic cosmographical writings. Ottoman scholar Taşköprülüzade mentions the “science of knowing the climates and divisions of the world” under the category of the science of astronomy (heyet) in his book on the classification of the sciences.[89] He writes that many marvelous and strange things in the world were known through this science and quotes al-Ḳazwīnī’s book as an example. [90] Taşköprülüzade offers some strange examples, including a black rose on which the name of God was written, and it is clear that he does not disregard these mythical accounts as invalid. For him, the marvels were the visible signs of God’s power. Ottoman authors like Bican also translated the classical texts on marvels, like al-Ḳazwīnī’s book, and used them as a source for their own texts.[91] Bican’s work on cosmography, titled Dürr-Meknun, which conveyed the marvels of creation together with many mythical stories of cities, mosques, statues, and ancient structures like Solomon’s throne, became very popular in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, although it was written in the mid-fifteenth century.

While these traditional books used and translated by Ottoman authors mostly included accounts of architectural marvels created in the past, Mehmed Aşık built upon his personal visits to evoke the various features of contemporary buildings such as the Selimiye Mosque and the Süleymaniye Mosque in the late sixteenth century. [92] Significantly, Mehmed Aşık called his book The Views of the Worlds and his text encompassed definitions of many cities and buildings that he visited during his travels. [93] Çiğdem Kafescioğlu states that travelers like Evliya Çelebi and Mehmed Aşık represented a certain Ottoman sensibility towards the perception of the built environment.[94] Mehmed Aşık’s writing demonstrates a scholar-traveler’s interest in contemporary artifices as a means to understand the marvels of the world. Since Mehmed Aşık was the first scholar to give a detailed account of Ottoman architecture, along with the cosmological and geographical features of the universe to entertain his readers, his text may indicate the increasing scholarly interest in architecture within Ottoman books on cosmography. Mehmed Aşık’s common metaphysical references to the cosmos, such as God’s throne, are followed by cosmological and geographical accounts of the shape of the earth and natural phenomena, such as the climates and the seas, uniting both forms of knowledge.[95] A scholar, Mehmed Aşık’s assessment of contemporary buildings as worthy of contemplation echoes Caʿfer’s understanding of architecture as inducing wonder and knowledge in his readers. The increasing interest in human artifacts included in books devoted to the wonders of creation must have been influential in the perception of architecture and artworks as wonders that could lead to a deeper knowledge of the world. According to Caʿfer, the Sultan Ahmed mosque (while under construction) had many marvelous (acībe) forms and extraordinary (garīb) features; the building was regarded as a marvel that one ought to scrutinize in order to comprehend its astonishing aspects.[96] The understanding of architectural works as sources of wonder is implied in the root of the word “acā’ib” that indicates astonishment or bewilderment when faced with an undecipherable event or phenomenon. Kafesçioğlu notes a shift in use, from the word “tarz-ı Rûm” (Rumi style) to the word “acâ’ib” (wonderful), in Evliya Çelebi’s definitions of buildings in the late seventeenth century.[97] Caʿfer’s writing occupies a place between Mehmed Aşık and Evliya Çelebi as a transitional text, which brought architecture and the cities to the forefront as main subjects in a book by trying to understand the foundations of artworks and their inner workings as preconditions for causing astonishment in the viewers. Caʿfer’s own wonder eventually led him to reveal architecture’s various connotations, ranging from the geometrical knowledge embedded in its body to harmonious sounds confirming its proportional arrangements.

In this framework, Caʿfer’s text sheds light on some of the cultural and intellectual motivations behind the practices of displaying and viewing precious artifacts as sources of wonder and wisdom in the Early Modern period.[98] Caʿfer not only stresses the wondrous features of the artworks but also how they evoked wonder in specific contexts due to their geometrical features or musical associations.[99] His narrations of his lived experiences of architecture and his poems reveal how the chain of relations in the cosmos, extending from the celestial bodies to colors, sounds, stones, and flowers, became perceptible through the medium of architecture, engendering wonder during its contemplation. This deliberation on the nature of artworks that inquires into the cause of astonishment is what makes his narratives significant and unique not only in an art-historical context but also within scientific cultures due to recent scholarly interest in the intermediary role of artifacts for knowledge production. As both Mehmed Aşık and Caʿfer imply, the various marvels of creation and human artifacts induce wonder in the audience while illuminating their minds and giving joy to their hearts.

8. A Book of Pleasure as a Gift

Much like Caʿfer’s alternative title, the name of Mimar Sinan’s book, Tuhfetü’l-Mi’mārīn (Choice Gift of the Architects) reveals the intentions of both the author and the architect.[100] Sinan’s complete architectural works are listed together with their patrons and they are understood as the architect’s gifts to these important figures consisting of the sultans, princes, princesses, sultanas, viziers, admirals, governors, the high officers of the imperial council, the aghas of the palace, as well as merchants and tradesmen.[101] But the use of the word “tuhfe” for the book is also noteworthy. In the prologue to his second chapter, Caʿfer emphasizes that Mehmed Agha was granted his positions due to his wondrous works (tuhaf işler), an expression that is used interchangeably with the word “tufhe,” meaning “gift.”[102] This is because “tuhfe” has the same root as “tuhaf,” which can be translated, in this context, as “wonderful.”[103] Thus, a gift was a source of wonder that would enchant and seduce the possessor.[104] Caʿfer emphasizes that no work similar to Mehmed Agha’s could be found in Istanbul’s rich markets, assuming his audience would compare what he described in his writings with their visual experiences in the bazaar. But Caʿfer was careful to call his story of Mehmed Agha’s works an ethical story (menkıbe); he imagined that the pleasure of envisioning Mehmed Agha’s wondrous gifts would be reinforced by their underlying moral messages, which he frequently incorporates into his narratives.[105]

Being an experienced master, Sinan was well acquainted with the seductive power of artworks: he first proposed that Mehmed Agha fashion a gift (tuhfe) as a memento (yādigār) for the sultan, in order to receive his grace (lutf) as well as salary.[106] Caʿfer mentions that Mehmed Agha made various gifts and mementos (yādigār) for the viziers and high officials, which indeed led to their endless favors. The simultaneous use of the word “memento” indicates that people expected their gifts to act as mnemonic objects, which reminded a person or a society of the skill of the donor or the maker. In Ottoman culture, a gift was a means of strengthening the friendly bond between two people, who shared a moment of intimacy in the image of an artwork. Hence, any gift would be chosen specifically to appeal to the interest of the recipient. Rather than being the product of an architect’s ego, a patron’s wish for an image of power, or a purely aesthetic object for exchange, the Risāle underscores the wondrous gifts’ mediating role to enhance life both on conceptual and sensuous levels. Caʿfer sees his book as a gift to the architect, who deserved to be appreciated and valued. Additionally, just as a master presented a book on geometry to Mehmed Agha as a memento when he was admitted to the corps of architects, the Risāle would be the symbol of their friendly bond and a commemoration of Mehmed Agha’s skill and passion for architecture.

But Caʿfer also envisioned his book as a memento from Mehmed Agha to his friends, whose content would enhance their lives. Caʿfer applies the analogy of a precious jewel also to Mehmed Agha’s “exalted body” (vücûd-ı şerif), as he calls it.[107] He likens the architect to a peerless Kirmani sword in its scabbard.[108] He states that it was not possible to know the value of jewels hidden beneath the scabbard or the sharpness of the blade unless one scrutinized it.[109] Thus, for Caʿfer, his readers had to learn about Mehmed Agha’s life story, artworks, and architectural deeds to comprehend his real nature. On the other hand, hearing about these accomplishments would serve as a source of wisdom to his readers. His intentions to convey sound advice to his audience through writing about architecture and the architect is evident in the following lines:

Because this [book] is like an excursion spot to mankind

How many gates were suddenly opened by it into the gates of wisdom.

From its auspicious advice, let us take good counsel in the world.

If [we do] not, the panels of the gates of [Paradise] will be coal-black with admonition.[110]

Caʿfer suggested to his friends that they copy and read his book as a pastime (eğlence), which resonates deeply with the metaphor of the pleasure spot (mesire) applied to his book.[111] Thus, he not only relates his book to wisdom but also to the notion of pleasure—understood as emotional knowledge in the Aristotelian sense. In this prosperous garden (ravza), many gates (bāb) would open to his readers to gain wisdom (hikmet). Moreover, they could apprehend the moral advice perceptible in the world if they became listeners. Caʿfer does not refrain from admonishing them should they not follow the advice laid out in his writings—implying that they should acquire a copy of his book. Otherwise, the gates of Paradise would be fated to remain black, a symbol of wrongdoing. In his final couplets, he continues: “Let us now conclude this safānāme (Book of Pleasure).”[112] This also explains why the first unnumbered folio of the Topkapı manuscript has the title Kitāb al-Miʿmāriyye ve Ṣafānāme (The Book on Architecture and the Book of Pleasure).[113] “Safā” has the double meaning of pleasure and purification. In a metaphoric sense, Caʿfer’s book becomes both a fountain of pleasure for his friends to enjoy, like a mesire (pleasure spot), and a gate of wisdom and advice to attain a catharsis in their lives, whose ensuing pure light would be radiated on the gates of Paradise. The Risāle thus becomes a gift to his readers to enrich their lives and knowledge as much as it was a gift for his benefactor, the chief architect Mehmed Agha, a patron of scholarly books. By defining his book as a book of pleasure (Safānāme n) in his final poem, Caʿfer emphasizes the pleasure derived from the knowledge and experience of architecture. This pleasure would be similar to the one gained from attaining knowledge through the contemplation of the marvels of the cosmos, making the Risāle a book worthy enough for both scholarly and courtly audiences.

Bibliography

Abdülkādir Efendi, Topçular Kâtibi. Topçular Kâtibi Abdülkādir Efendi Tarihi, ed. Ziya Yılmazer (Ankara: TTK, 2003), vol. 1

Afyoncu, Fatma. XVII. yüzyılda Hassa Mimarları Ocağı. Ankara: T.C. Kültür Bakanlığı, 2001.

Andrews, Walter G. “A Critical-Interpretive Approach to the Ottoman Turkish Gazel.” International Journal of Middle East Studies 4 (1973): 97-110.

———. An Introduction to Ottoman Poetry. Minneapolis: Bibliotheca Islamica, 1976.

———. “Speaking of Power: The Ottoman Kaside.” In Qasida Poetry in Islamic Asia and Africa, Vol. I: Classical Traditions and Modern Meanings, 281-300. Leiden: E. J. Brill, 1996.

Arseven, Celâl Esad. Türk Sanatı Tarihi: Menşeinden Bugüne Kadar. Istanbul: Millî Eğitim Basımevi, 1961.

Bağcı, Serpil. “From Adam to Mehmed III: Silsilename.” In The Sultan's Portrait: Picturing the House of Osman, edited by Selmin Kangal and Priscilla Mary Işın, 188-202. Istanbul: Topkapı Sarayı Müzesi, İşbank, 2000.

Breebaart, Deodaat Anne. “The Fütüvvet-nāme-i kebīr. A Manual on Turkish Guilds.” Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient (1972): 203-215.

Caʿfer Efendi. Risāle-i Miʿmāriyye: An Early-Seventeenth-Century Ottoman Treatise on Architecture. Facsimile with Translation and Notes, edited and translated by Howard Crane. Leiden; New York: E. J. Brill, 1987.

———. Risâle-i Mi’mâriyye, edited by I. Aydın Yüksel. Istanbul: İstanbul Fetih Cemiyeti, 2005.

Cerasi, Maurice. “Late-Ottoman Architects and Master Builders.” Muqarnas 5 (1988): 87–102.

Coşkun, Feray. “A Medieval Islamic Cosmography in an Ottoman Context: A Study of Mahmud el-Hatib’s Translation of the Kharidat al-ʿ Ajaʾib’.” Master's thesis, Boğaziçi University, 2007.

Çelebi, Evliya. Evliya Çelebi Seyahatnâmesi: Istanbul, ed. Robert Dankoff, Seyit Ali Kahraman and Yücel Dağlı, 9 vols. (Istanbul: YKY, 2006), vol. 1

Çelebi, Kınalızâde Ali. Ahlâk-i Alâî, edited by Fahri Unan (Ankara: TTK, 2014)

Dubler, C. E. “ʿAd̲j̲āʾib.” Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition, edited by Peri Bearman et al. Leiden: Brill, 2009.

Fairchild Ruggles, D. (editor). Islamic Art and Visual Culture: An Anthology of Sources. Malden: Wiley-Blackwell, 2011.

Faroqhi, Suraiya. “Guildsmen and Handicraft Producers.” In The Cambridge History of Turkey, edited by Suraiya Faroqhi, 336-355. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006.

Fetvacı, Emine. “Music, Light, and Flowers.” Journal of Turkish Studies 32 (2008): 222–24.

———. Picturing History at the Ottoman Court. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2013.

Gökyay, Orhan Şaik. “Risale-i Mimariyye, Mimar Mehmed Ağa, Eserleri.” In Ord. Prof. İsmail Hakkı Uzunçarşılı'ya Armağan, 107-206. Ankara: Türk Tarih Kurumu, 1976.

Hâfız-zâde. Kalemden Kelâma: Risâle-i Hat, edited by Sadettin Eğri. Istanbul: Kitabevi, 2005.

Hagen, Gottfried. “Afterword: Ottoman Understandings of the World in the Seventeenth Century.” In Robert Dankoff, An Ottoman Mentality: The World of Evliya Çelebu, 217–19. Leiden: Brill, 2006.

———. “The Order of Knowledge, the Knowledge of Order: Intellectual Life.” The Cambridge History of Turkey 2 (2012): 1412–13.

Hunsberger, Alice C. “Marvels.” In Encyclopedia of the Qur’ān. Leiden; Boston: Brill, 2003.

İnalcık, Halil. The Emergence of Big Farms, Çiftliks: State, Landlords, and Tenants. London: Variorum Reprints, 1985.

Imber, Colin. “The Cultivation of Wasteland in Hanafi and Ottoman Law.” Acta Orientalia Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae 61, no. 1 (2008): 101-112.

Kafadar, Cemal. “Self and Others: The Diary of a Dervish in Seventeenth Century Istanbul and First-Person Narratives in Ottoman Literature.” Studia Islamica 69 (1989): 121-150.

Kafescioğlu, Çiğdem. “Rûmî Kimliğin Görsel Tanımları: Osmanlı Seyahat Anlatılarında Kültürel Sınırlar ve Mimari Tarz [Visual Definitions of Rumi Identity: Cultural Boundaries and Architectural Style in Ottoman Travel Narratives].” Journal of Turkish Studies: In Memoriam Şinasi Tekin 2, no. 31 (2007): 57-65.

Kale, Gül. “Unfolding Ottoman Architecture in Writing: Theory, Poetics, and Ethics in Caʿfer Efendi’s “Book on Architecture.” Ph.D. dissertation, McGill University, 2014.

———. “Risale-i Mi’mariyye: An Early-Seventeenth-Century Ottoman Treatise on Architecture.” International Journal of Turkish Studies 21, no. 1/2 (2015): 177.

———.“Visual and Embodied Memory of an Ottoman Architect: Traveling on Campaign, Pilgrimage, and Trade Routes in the Middle East.” In The Mercantile Effect: Art and Exchange in the Islamicate World During the 17th and 18th Centuries, edited by Sussan Babaie and Melanie Gibson, 124–40. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2017.

———. “Intersections Between the Architect’s Cubit, the Science of Surveying, and Social Practices in Caʿfer Efendi’s Seventeenth-Century Book on Ottoman Architecture.” Muqarnas Online 36, no. 1 (2019): 131–177.

———.“From Measuring to Estimation: Definitions of Geometry and Architect-Engineer in Early Modern Ottoman Architecture.” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 79, no. 2 (2020): 132-151.

———. “Stuff of the Mind: Mother-of-Pearl Table Cabinets of Ottoman Scholars in the Early Modern Period.” In Living with Nature and Things, edited by Bethany Walker and Abdelkader Al Ghouz, 577–638. Göttingen: V&R Unipress, 2020.

———. “Harmonious Relationships: Sounds and Stones in Ottoman Architecture in the Making.” Architectural Histories 10, no. 1 (2022).

Konyalı, İbrahim Hakkı. Mimar Koca Sinan: Vakfiyyeleri, Hayır Eserleri, Hayatı, Padişaha Vekâleti, Azadlık Kâğıdı, Alım, Satım Hüccetleri. Istanbul: Topçubaşı, 1948.

Lewicki, T.. “al-Ḳazwīnī.” Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition, edited by Peri Bearman et al. Leiden: Brill, 2009.

Mehmed, Âşık. Menâzırü’l-Avâlim, edited by Mahmut Ak. Ankara: TTK Yayınları, 2007.

Ménage, V. L. “Devs̲h̲irme.” Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition, edited by Peri Bearman et al. Leiden: Brill, 2009.

Mimar Sinan and Sai Mustafa Çelebi. Yapılar Kitabı: Tezkiretü'l-Bünyan ve Tezkiretü'l-Ebniye: (Mimar Sinan’ ın Anıları), edited by Hayati Develi. Istanbul: Koçbank, 2002.

———. Sinan's Autobiographies: Five Sixteenth-Century Texts, edited by Howard Crane and Esra Akın, preface by Gülru Necipoğlu. Leiden; Boston: Brill, 2006.

Naima, Mustafa. Naima Tarihi, edited by Zuhuri Danışman. Istanbul: Z. Danışman Yayınevi, 1967.

Necipoğlu, Gülru. “Reviewed Work: Risâle-i Mi’mâriyye: An Early Seventeenth-Century Ottoman Treatise on Architecture by Caʿfer Efendi; Howard Crane (ed.).” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 49, no. 2 (1990): 210–13.

———. “The Life of an Imperial Monument: Hagia Sophia after Byzantium.” In Hagia Sophia from the Age of Justinian to the Present, edited by Robert Mark and Ahmet S. Çakmak, 195-225. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992.

———. The Topkapi Scroll: Geometry and Ornament in Islamic Architecture. Los Angeles: Getty Publications, 1996.

———. The Age of Sinan: Architectural Culture in the Ottoman Empire. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2005.

Öz, Tahsin. Mimar Mehmed Ağa ve Risale-i Mimariye. Istanbul: Cumhuriyet Matbaası, 1944.

Qaddūmī, Ghādah Ḥijjāwī and Aḥmad ibn al-Rashīd Ibn al-Zubayr. “A Medieval Islamic Book of Gifts and Treasures: Translation, Annotation, and Commentary on the Kitab al-Hadaya wa al-Tuhaf.” Ph.D. dissertation, Harvard University, 1990.

Rabbat, Nasser. “Ajib and Gharib: Artistic Perception in Medieval Arabic Sources.” The Medieval History Journal 9, no. 1 (2006): 99–113.

“Risāla.” In Encyclopedia of Islam, Second Edition, edited by Peri Bearman et al. Leiden: Brill, 2009.

Sâfî, Mustafa. Mustafa Sâfî’nin Zübdetü’t-tevarîh’i, ed. I. H. Çuhadar (Ankara: TTK, 2003), vol. 1

Tanman, Baha. “Settings for the Veneration of Saints.” In The Dervish Lodge: Architecture, Art, and Sufism in Ottoman Turkey, edited by Raymond Lifchez, 130–75. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1992.

Taşköprüzāde, Aḥmad ibn Muṣṭafā. Mevzuat’ül ulûm: İlimler ansiklopedisi

[Encyclopedia of the sciences], ed. Mümin Çevik, trans. Kemâluddin Muḥammed Efendi, 2 vols. (Istanbul: Üçdal, 1966), vol. 1

Terzioğlu, Derin. “Autobiography in Fragments: Reading Ottoman Personal Miscellanies in the Early Modern Era.” In Autobiographical Themes in Turkish Literature: Theoretical and Comparative Perspectives, edited by Olcay Akyıldız, Halim Kara, and Börte Sagaster, 83-99. Würzburg: Ergon Verlag in Kommission, 2007.

Tûsî, Nasîruddin. Ahlâk-ı Nâsırî, edited by Tahir Özakkaş. Istanbul: Litera Yayıncılık, 2007.

Von Hees, Syrinx. “The Astonishing: A Critique and Re-reading of 'Aga'ib Literature.” Middle Eastern Literatures 8, no. 2 (2005): 101-120.

Woodhead, Christine. “From Scribe to Litterateur: the Career of a Sixteenth-Century Ottoman Katib.” British Society for Middle Eastern Studies. Bulletin 9, no. 1 (1982): 55-74.