Rhetorics of Power: Michelangelo and the Medici Manuscripts

Reception date: March 28, 2023. Acceptance date: August 28, 2023. Date of modifications: September 09, 2023.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.25025/hart15.2023.07

Ph.D. McGill University. Architectural Historian. Premodern architectural design, bodies, materials, and histories of medicine. Lecturer at the College of Architecture and Design at the University of Tennessee, Knoxville.

Abstract:

The present study theorizes the ornamentation of the Laurentian Library’s vestibule as early modern architectural rhetoric and examines how architectural design constructed societal norms pertaining to articulation and eloquence, influence and power. I frame the Laurentian Library and its Medici manuscript collection as apparatuses that challenged and legitimized perceptions of the Medici’s constructed nobility and overbearing political identity. The study unfolds one manner in which early modern Florentine art production centralized around Medici patronage to glorify their lineage and the emerging Tuscan duchy.

Keywords: early modern library, book collection, knowledge production, patronage, architectural ornament, Monastery of San Marco, Laurentian Library, Florence.

Retóricas de poder y disidencia: Michelangelo y 1000 manuscritos Medici

Resumen:

Teorizando sobre la ornamentación del vestíbulo de la Biblioteca Laurenciana, en particular, la antítesis ornamental que desplaza y desconcierta, como una retórica arquitectónica de la época moderna temprana, este ensayo examina cómo el diseño arquitectónico construyó normas sociales relacionadas con la articulación y elocuencia, la influencia y el poder. Enmarco la Biblioteca Laurenciana y su colección de manuscritos Medici como dispositivos que legitimaron percepciones de la nobleza Medici y su abrumadora identidad política. Para llegar a la biblioteca como instrumento de poder, trazo la ruta de los manuscritos Medici, que instigaron el diseño y la construcción de la Biblioteca Laurenciana, y concluyo reflexionando sobre los dispositivos retóricos del vestíbulo con un enfoque en los "soportes" de Michelangelo. Siguiendo los libros desde Florencia a Roma y de vuelta a Florencia, el estudio también señala las relaciones entre los monasterios de San Marco y San Lorenzo, el gobierno florentino y los Medici, quienes buscaron posicionarse y vindicar su soberanía sobre Florencia a través de Dios.

Palabras clave: Retóricas de poder, Michelangelo, Manuscritos Medici, Biblioteca Laurenciana, Identidad política

Retórica do Poder e da Dissidência: Michelangelo e 1000 Manuscritos Medici

Resumo:

Ao teorizar a ornamentação do foyer da Biblioteca Laurentiana, em particular a antítese ornamental que desloca e mistifica, como uma retórica arquitetônica do início da modernidade, este ensaio examina como o projeto arquitetônico construiu normas sociais relacionadas à articulação e eloquência, influência e poder. Enquadro a Biblioteca Laurenciana e sua coleção de manuscritos Médici como dispositivos que legitimaram as percepções da nobreza dos Médici e sua identidade política esmagadora. Para chegar à biblioteca como um instrumento de poder, traço a rota dos manuscritos Medici, que instigaram o projeto e a construção da Biblioteca Laurentiana, e concluo refletindo sobre os dispositivos retóricos do foyer com foco nos “suportes” de Michelangelo. Seguindo os livros de Florença a Roma e de volta a Florença, o estudo também aponta para as relações entre os mosteiros de San Marco e San Lorenzo, o governo florentino e os Medici, que buscavam posicionar e reivindicar sua soberania sobre Florença por meio de Deus.

Palavras-chave: Retórica do poder, Michelangelo, Manuscritos de Medici, Biblioteca Laurentiana, Identidade política

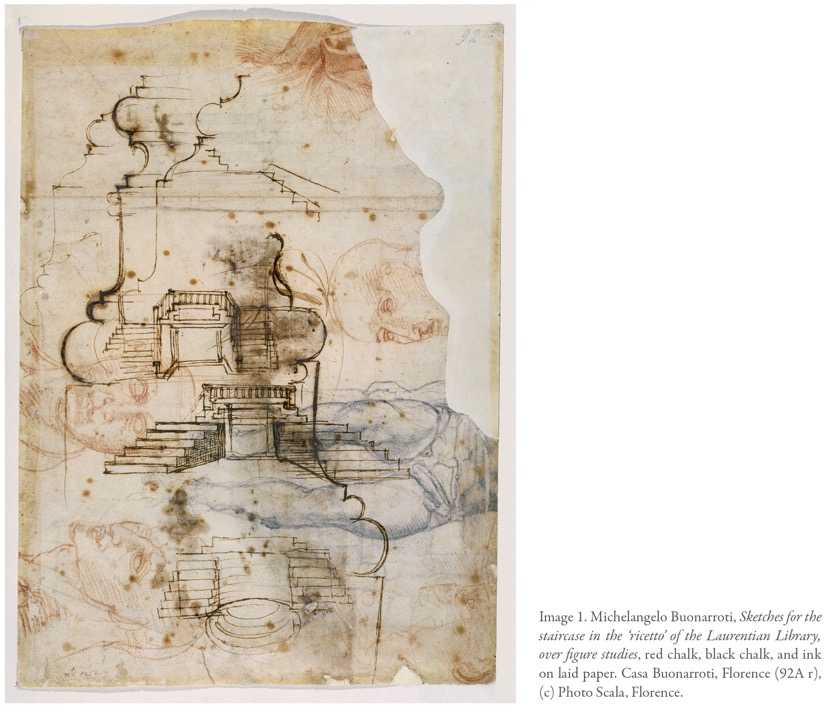

In spite of being a site of constant bustle and noise, the San Lorenzo quarter in Florence, comprising the San Lorenzo church and cloister, gives an impression of spiritual composure. The San Lorenzo monastery dominates the district, its literal and symbolic serenity enduring as workshops, restaurants, and tourists assemble and scatter centennially. The sentiment and notion of the cloister’s tranquility and stillness seem to persist unaffected alongside its unfinished façade. However, a step inside the cloister unravels an unruly crevasse. At the threshold of the Laurentian Library, San Lorenzo’s repose is unsettled by the library vestibule’s confounding dimness and robust materiality. Michelangelo’s cascading stairs and soaring walls cast movement instead of poise, along with an irresistible, agitating sense of wonder.[1] The vestibule impels this uncanny dynamism by design (Figure 1). In addition to his drawings, Michelangelo used words to describe his ideas for the anteroom in a letter from 1555: “I recall a certain staircase, as it were in a dream […] diminishing and narrowing […] one after the other continuously as they ascend towards the door.”[2]

In this essay I will theorize the ornamentation of this vestibule—particularly the ornamental antithesis that displaces and perplexes—as early modern architectural rhetoric and examine how architectural design participated in constructing societal norms pertaining to articulation and eloquence, influence and power. I frame the Laurentian Library and its Medici manuscript collection as apparatuses that both challenged and legitimized perceptions of the Medici’s nobility and overbearing political identity. To build this account of the library as an instrument of power, I begin by tracing the route of the Medici manuscripts—which instigated the design and construction of the Laurentian Library—and conclude by reflecting on the vestibule’s ornamental devices with a focus on Michelangelo’s brackets. By following the books from Florence to Rome and back to Florence, I also point to the relations between the San Marco and San Lorenzo monasteries, the Florentine government, and the Medici, who sought to position and vindicate their sovereignty over Florence via God.

1. The Libreria Medicea Privata and the Libreria Medicea Publica

In September 1433, the expatriated Medici took refuge in Venice.[3] Michelozzo Michelozzi (1396-1472), an architect and pupil of Brunelleschi (1377-1446) and Donatello (1386-1466), accompanied the current paterfamilias, Cosimo di Giovanni de’Medici (1389-1464) and the Medici family in exile. According to the artist and chronicler Giorgio Vasari (1511-1574), while in Venice Michelozzo “made by Cosimo’s order, and at his expense, the library of the monastery of San Giorgio Maggiore […] which was finished not only with walls, seats, wood-work and other ornaments, but filled with many books. This constituted the diversion and pastime of Cosimo until he was recalled in 1434.”[4] More than a mere diversion, with the library’s construction Cosimo sent a message to Florence and established the family as a powerful presence in Venice. Indeed, building a library signified a certain level of sophistication, which ascertained Cosimo’s place in the patriarchal hierarchies and brought significant political influence, consolidating his social standing.[5]

Similarly, Cosimo renovated San Marco to cement his reputation and influence in Florence. After the Medici’s 1434 return to Florence, Pope Eugene IV (Gabriele Condulmer, 1383-1447) suggested that Cosimo should “sanctify” his vast fortune by rebuilding the monastery. San Marco had been a Sylvestrine monastery until the order was accused of negligence and ordered to vacate the convent in 1418. They left in 1437, allotting the site to the Dominicans, who ostensibly moved into a deteriorated monastery and lived in damp rooms that barely remained erect. Once the Dominicans were at San Marco, Cosimo commissioned Michelozzo to rebuild the cloister.[6]

The same year, Niccolò de Niccoli (1364-1437), a Florentine leading antiquarian, copyist of manuscripts, and one of the learned individuals surrounding Cosimo, passed away. During his lifetime, Niccoli had engaged people such as Poggio Bracciolini (1380-1459) to act as manuscript hunters across Europe—and as far as Constantinople—to search, recover, and acquire treasured volumes on his behalf.[7] During his travels Poggio visited various monasteries, including the Carolingian monastery St. Gall in St. Gallen, occasionally complaining about the conditions manuscripts were kept in and “rescuing” select volumes by thrusting them under his robe.[8] After his death, Niccoli left his library, instructions on its further use, and his debts to Cosimo de’Medici.[9] To gain full possession of the library, Cosimo agreed to obey Niccoli’s directives, canceled his debts, and set about finding an appropriate place for the 400 manuscript volumes.[10] Cosimo instructed Michelozzo, who was already at work on the renovation of San Marco, to extend his alterations to include a larger reading room. The library of San Marco was re-constructed, according to Vasari: “80 braccia long and 18 braccia broad, furnished with 64 cases of cypress wood full of the most beautiful books, many of them illuminated by Fra Angelico and his school.”[11] The main library hall, accessible from the upper cloisters under which the Dominican friar Girolamo Savonarola (1452-1498) was arrested fifty years later, was divided into three aisles by two rows of eleven columns, lit by twelve windows on both sides, and furnished with sixty-four wooden desks to which Niccolo’s splendid collection was chained.[12]

Despite using a similar book-depositing system as previous monastic libraries, the San Marco library differed in content and purpose. According to Vasari’s descriptions, the new library at San Marco kept the volumes in book chests—a characteristic of the medieval monastic library before the dissemination of print, book closets, and desk shelves.[13] In this arrangement the books were roughly categorized by subject, size, and acquisition.[14] The books that were chained to the desks were usually not those of greater value, but rather those that were most commonly used.

Apart from these similarities, the San Marco library differed from the typical monastic library, firstly by its content: the classics section was greatly enlarged and classified independently, and there was a lack of books deemed essential for a monastic library.[15] Secondly, it diverged in its architecture and by the need to express Cosimo’s social and political standing formally and materially. In other words, the cloister’s character and intrinsic piety were being employed as construction sites for Cosimo’s and the Medici’s societal pre-eminence. Coupled with a sanctioned literary heritage, the architecture at San Marco articulated status and corroborated ideas regarding familial lineage. Lastly, in contrast to previous monastic collections, the library at San Marco varied in its conception. In recognition of Niccoli’s wish, it was now open to all the learned citizens of Florence. Thus, some scholars consider it to be the first “modern” public library on the Italian peninsula.[16]

After setting up San Marco’s library, Cosimo decided to assemble a domestic library as well. He began by commissioning the inventarium—the bibliographical canon of selected works assumed essential for the establishment of any honorable library—from Tommaso Parentucelli (1397-1455), a famed patron of the arts that would later impel the rebuilding of St. Peter’s in Rome as Pope Nicholas V.[17] Cosimo also enlisted the help of the cartolaio Vespasiano da Bisticci (1421-1498), who secured 200 manuscripts for Cosimo’s personal corpus using the labor of forty-five scribes over twenty-two months.[18] The bookseller most likely also arranged the binding of the manuscripts. While exploring the 1456 Medici catalogue, historian Dorothy M. Robathan (1898-1991) noticed commentaries explaining how the private Medici collection was categorized and bound in different colors according to the books’ subjects. In Robathan’s words: “the manuscripts of sacred literature were bound in blue, the grammatical works in yellow, the poetical volumes in purple, while the historical tomes rejoiced in covers of red.”[19]

Cosimo succeeded in building and equipping three libraries during his lifetime. Even though the Medici were renowned patrons of the arts, having commissioned their palazzi, chapels, busts, and libraries from famous artists and architects, they were rarely directly associated with the sponsorship of other politically less conspicuous institutions like the Florentine Ospedale degli Innocenti.[20]

The library of San Marco lost its most generous benefactor with Cosimo’s death in August 1464. In terms of book donations, the Medici’s support for the library halted. Cosimo’s son, Piero di Cosimo de’Medici (1416-1469) donated two books (commentaries by Versorius and Aquinas to Aristotle) and Piero’s son, Lorenzo di Piero de’Medici (1449-1492) donated only one.[21] Rather than bequeathing the Dominicans, Piero was determined to broaden the libreria medicea privata at the Medici palace. Piero collected manuscripts even before Cosimo’s death. The 1464/65 inventory of Piero’s possessions includes his personal manuscript collection and his inheritance from Cosimo, and thus reveals Piero’s contribution to the private library.[22] According to historian Francis Ames-Lewis, Piero was a great enthusiast when it came to collecting manuscripts written in the Tuscan vernacular.[23] The 1464/65 inventory lists thirteen books in the “libri sacri” section, seven volumes in the “arte” section (all by Cicero), and eighteen books in the “storia” section—the largest library subdivision, which contained the highest percentage of Piero’s personally commissioned manuscripts.[24] Following Piero, Lorenzo the Magnificent had a similar determination. With the help of the scholar Janus Lascaris (1445-1535) and the scholar and poet Angelo Poliziano (1454-1494), both operating as book hunters, Lorenzo added 200 Greek manuscripts—the greatest number of Greek manuscripts collected in the period—to the private library between 1489-1492.[25] At the time of Lorenzo’s death, in April 1492, the Medici private library numbered more than 1000 volumes (Figure 2).

Following renewed political turmoil in Florence, the Medici private collection was relocated in its entirety to San Marco in 1494. Two years after Lorenzo the Magnificent’s death, his son Piero di Lorenzo de’Medici (1472-1503), known as Piero the Unfortunate, was banished from Florence. In the wake of Piero’s exile, the insurgent Florentine crowds sacked the Medici palace. Notably, during the pillaging, the city’s main governmental body, the Signoria, safeguarded the Medici’s private library. The Signoria’s delegates parceled the library in seventeen cases and deposited the unspoiled collection at the San Marco monastery.[26] In October 1495, the San Marco friars made a loan of 2,000 florins to the Signoria and formally accepted the books as a security deposit.[27] In January 1497, the Signoria fully bestowed the ownership of the Medici books to San Marco to settle the debt, which they were supposedly unable to pay. The libreria medicea privata and the libreria medicea publica were now united under the same roof for the first time.

Pico della Mirandola’s (1463-1494) precocious death sheds some light on the politics at play in the Signoria’s contract with the Dominicans. In November 1494, just before the friars made the loan to the Signoria, the nobleman, writer, and philosopher from Mirandola died asking for the posthumous housing of both his body and his library at San Marco. Pico’s collection had 1186 manuscripts consisting of religious and philosophical works suited for a monastic library, and Savonarola delivered the funeral address demonstrating a rapport between Pico and the Dominicans.[28] Pico had decided to hand down his entire collection to the Dominicans for 500 florins. However, the friars did not purchase Pico’s volumes and bought Lorenzo’s smaller and significantly more expensive collection instead. According to historians such as Berthold L. Ullman, this may have meant that the friars were unable to afford large manuscript collections but were acting through Medici agents, finding it in their interest to preserve, for the time being, the Medici’s library at San Marco.[29] The Dominicans kept the Medici collection until 1508, when Lorenzo’s son, Giovanni di Lorenzo de’Medici (1475-1521), later Pope Leo X, expressed interest in his father’s library. He procured the books from San Marco and transferred them to his private library at the Palazzo Madama at Sant’Eustachio in Rome.[30]

After the Medici library was reclaimed from San Marco, the monastic library started experiencing a slow and constant decline. Even before the establishment of the new building for the Laurentian Library, the monastery of San Lorenzo had already acquired a large selection of San Marco’s most precious manuscripts. Ullman and Stadter have identified twenty-two Latin and seventy Greek manuscripts from the San Marco catalogue at the Laurentian’s fondo mediceo.[31] The mode of the actual transfers is unknown. It has been speculated that after Cosimo I de’Medici (1519-1574) came to power as the second Duke of Florence in 1537, he saw the San Marco library as Medici property and found little objection in transferring volumes from one to another “Medici library.”[32]

2. Tenacious Brackets

In 1523, the Medici private collection was ready to go back to Florence. Pope Clement VII, or Giulio di Giuliano de’Medici (1478-1534), the illegitimate son of Giuliano di Pietro de’Medici, commissioned the by-then esteemed artist, poet, and architect Michelangelo Buonarroti (1475-1564) for the building of the Laurentian Library.[33] The new library was to be adjacent to the church and monastery of San Lorenzo, which was rebuilt by Filippo Brunelleschi (1377-1446) under Cosimo the Elder and intimately associated with the Medici. Michelangelo was involved in the design and construction of the Laurentian from 1524 to 1533.[34] The foundations were begun in 1524, the walls and roof finished by 1527, and overall construction lasted until 1559.[35] Michelangelo’s correspondence with Pope Clement VII demonstrates the Medici’s ambition, whereas his drawings attest to his design process.[36] Before the library commission, Michelangelo designed and partly executed the Medici Chapel at San Lorenzo that enclosed the tombs of Giuliano, Duke of Nemours, and Lorenzo the Magnificent, Duke of Urbino. Art and architectural historian David Hemsoll contends that the Medici Chapel and the Laurentian Library make evident Michelangelo’s design methodology that relied upon transforming architectural prototypes to achieve “novelties,” including San Lorenzo’s Old Sacristy by Brunelleschi and the Pantheon in Rome.[37] According to art historian Cristina Acidini Luchinat, the Medici preferred Michelangelo because he had ties to Lorenzo the Magnificent. In her words: “during the sixteenth century Michelangelo embodied for the Medici and for Florence the finest living proof of an age still fresh in the collective memory, a period hailed in Medici propaganda as a golden age.”[38]

Michelangelo’s work at the Laurentian Library has been meticulously studied and debated.[39] Jacob Burckhardt declared the vestibule incomprehensible and, at first, it was seen as the epitome of Mannerist decadence, whereas Rudolf Wittkower and James Ackerman reflected on the library’s design to recuperate its formal and structural qualities.[40] Recalling early modern ideas about affect and empathy, Cammy Brothers persuasively challenges the limitations of the interpretative polemic in reference to the Laurentian Library, requesting an analytical cultivation of the significance of movement in architectural history.[41] Building upon Brothers, and instead of detailing Michelangelo’s practices on paper and site, I turn to consider the vestibule’s ornamentation and renowned brackets (Figure 3). To clarify, as I turn to reflect on the vestibule’s brackets, I will not be subordinating architectural ornament to the concept of décor. Instead, I approach Michelangelo’s brackets as expressive, material forms corresponding to poetic, rhetorical figures, following scholars like David Summers. According to Summers, in poetry movement was most often portrayed through the figure of antithesis, which, analogously, the plastic arts echoed in their use of contrapposto.[42]

If ornament can be framed as an architectural rhetorical figure—at once a formal, structural, and creative element—what can we learn about the brackets’ expressive and symbolic qualities through their formal introduction and structural intrusion, and vice versa? I speculate that the brackets’ formal discrepancies shed light on political and ideological divergences developing amid the artist, the populace, and the Medici.[43] Carol E. Quillen argues that redefining words allowed Francesco Petrarca (1304-1374), the poet and celebrated proponent of the Tuscan vernacular language, to step out of the long-standing associations built into linguistic units as implications, exposing biases and, in turn, enabling creation against what was taken for granted.[44] Similarly, it can be argued that Petrarca’s admirer, Michelangelo, given the task of eloquently articulating the Medici’s social standing, appropriated the bracket, redefined it, and probed the predisposition of Medici patronage. Shortly put: a devout, awe-inspiring anteroom would have revealed the Medici as inherently pious patrons—but Michelangelo’s vestibule is not merely astounding. It is also hazy and disconcerting.

A significant part of the vestibule’s perturbing atmosphere rests on its proportions, ornaments, and, for my purposes, its brackets.[45] The vestibule’s twelve pairs of brackets are carved from monolithic blocks of gray sandstone referred to as pietra del fossato, pietra serena, or simply macigno, found in abundance around Florence.[46] The brackets, sometimes labeled as volutes or consoles, are geometrically demanding scroll-like ornaments developed to compositional perfection in the Laurentian’s anteroom. For example, four of the twelve pairs appear forced into the room’s corners by their scale and distributive rhythm (Figure 4). Despite being unable to fully develop their individual forms and take up personal space, the corner brackets couple and transmute into each other in a manner that has been described as “mating rather than meeting.”[47] Mauro Mussolin describes the corner brackets as the epitomes of Michelangelo’s overall conception of architecture due to their concomitant geometric precision and spatial fluidity.[48] However, it is the conflation of the brackets’ aptness and precarious ensnarement that imparts the rhetorical contrapposto and antithesis that augments the vestibule’s perplexing character. Moreover, all twelve bracket pairs are placed under the recessed, load-bearing columns that sustain the walls and roof.[49] Occupying the lower level of the towering walls, the brackets directly inhabit the visitors’ realm at eye level. In this context, they are powerful and large presences, roughly one meter in height, standing elevated from the floor. Beneath the sunken columns, the brackets project forward from the wall planes, promptly demonstrating to the visitors that, even though they seem to be supporting the columns, they sustain only themselves. In this manner, Michelangelo expressed proximity and parallelism, two strongly contrasted ideas, and obscured the relationship between geometric and organic shapes, load and support, openness and reticence, creatively generating affective spatial antitheses and promoting surprise, queries, and hesitations.

By architecturally disturbing the seamless incorporation of the public library into the monastery, which Michelozzo accomplished at San Marco, Michelangelo disrupted the Medici’s perfunctory appropriation of San Lorenzo’s symbolic and literal piousness. Accurately identifying whether Michelangelo’s design motives were political, personal, or frivolous is beyond the scope of the paper. I suspect that, at the Laurentian, architectural design challenged established societal norms regarding expressiveness and eloquence, contesting Medici power on sacred ground. Architecture, in this case, proved less conductive to political authority than the manuscript collection. Indeed, this was not the first time that Michelangelo reconsidered the bracket on a Medici project. He had previously transformed the element with the “kneeling window” at the Palazzo Medici in Florence and in the wall niches in the Medici Chapel at San Lorenzo. The “kneeling window” was bound to the Medici and consecrated as a Florentine treasure in Francesco Bocchi’s (1548-1618) Florentine guide, Le bellezze di Fiorenza (1591).[50] Continuing his play with brackets already associated with the Medici, in the Laurentian Michelangelo relayed a conceptual and sensible distance which, in turn and as he claimed in his letter, created a dreamy and almost incongruous place.

3. Postscript

A library is a place where books and other materials are available for people to use and borrow, a room where books are kept, or a collection of similar things. The interchangeable meaning of the notion, indicating a place, a collection, or both together, best illustrates the intertwining of the efforts of gathering knowledge and providing a designated area under a more extensive endeavor to lend the world a semblance of meaning and order. Libraries, thus, are simultaneously collections of books, places, and cultural and ideological concepts. The historian of the book, Richard Gameson, reminds us that libraries are means of organizing and presenting knowledge: “for the way in which books are classified, and with what they are juxtaposed, can be as important as their content in defining how they are used and perceived.”[51] As such, the library has often served as a political apparatus, as creators of libraries were either powerful or wealthy individuals and institutions that relied on their exclusive collections to build the desired images of themselves alongside corresponding architectural and cultural legacies.

In Florence,

under Medici patronage, San Marco and San Lorenzo emerged as libraries for

public use and as acceptable and noble devices for achieving visibility, while

consolidating and perpetuating social and political standing. San Marco,

conceived by Cosimo the Elder, who was not a duke and treaded more carefully in

republican Florence, was more modest in scope, design, and built with attention

to the collections it housed and the manuscripts it collected. The Laurentian,

commissioned by Clement VII, a Medici pope, and while Cosimo I de’Medici was

Duke of Florence, was grander and saw no objection in amassing a collection by

appropriating various volumes from other collections. Somewhat later, towards

the mid-sixteenth century, Florentine art production would be almost entirely

centralized around the Medici as capital that was diverted from wars and

redirected towards the arts, which in turn, more than ever before, devoted

themselves to the dynastic glorification of the Medici and the Tuscan duchy.

Bibliography

Acidini Luchinat, Cristina. The Medici, Michelangelo, and the Art of Late Renaissance Florence. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2002.

Ackerman, James S. The Architecture of Michelangelo. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1986.

Ames-Lewis, Francis. The Library and Manuscripts of Piero di Cosimo de’Medici. London: Courtauld Institute of Art, 1977.

Argan, Giulio Carlo and Bruno Contardi. Michelangelo Architect. Milan: Electa Architecture, 2004.

Barocchi, Paola (ed.). La vita di Michelangelo nelle redazioni del 1550 e del 1568. Milan: Ricciardi, 1962.

Bracciolini, Poggio, Niccolò Niccoli, and Phyllis Walter Goodhart Gordon. Two Renaissance Book Hunters: The Letters of Poggius Bracciolini to Nicolaus de Niccolis. New York: Columbia University Press, 1991.

Brothers, Cammy. Michelangelo, Drawing, and the Invention of Architecture. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2008.

———. “Michelangelo’s Laurentian Library, Music and the Affetti.” In Das Auge der Architektur, edited by Andreas Beyer, Matteo Burioni, and Johannes Grave, 321-353. Munich: Wilhelm Fink Verlag, 2011.

Buonarroti, Michelangelo. The Letters of Michelangelo. Edited and translated by E. H. Ramsden. London: Peter Owen Limited, 1963.

Catitti, Silvia. “The Laurentian Library: Patronage and Building History.” In San Lorenzo: A Florentine Church, edited by Robert W. Gaston and Louis Alexander Waldman, 385-386. Florence: Villa I Tatti, The Harvard University Center for Italian Renaissance Studies, 2017.

Cooper, James S. “Michelangelo’s Laurentian Library: Drawings and Design Process.” Architectural History 54 (2011): 53.

Elam, Caroline. “‘Tuscan Dispositions’: Michelangelo’s Florentine Architectural Vocabulary and Its Reception.” Renaissance Studies 19, no. 1 (2005): 46-82.

Forster, Kurt W. “Metaphors of Rule: Political Ideology and History in the Portraits of Cosimo I de’Medici.” Mitteilungen des Kunsthistorischen Institutes in Florenz 15, no. 1 (1971): 65–104.

Gameson, Richard. “The Image of the Medieval Library.” In The Meaning of the Library: A Cultural History, edited by Alice Crawford, 31-71. Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press, 2015.

Gundersheimer, Werner L. “Patronage in the Renaissance: An Exploratory Approach.” In Patronage in the Renaissance, edited by Guy Fitch Lytle and Stephen Orgel, 3-24. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2014.

Harris, Michael H. History of the Libraries in the Western World. Metuchen and London: The Scarecrow Press, Inc., 1984.

Hemsoll, David. “The Laurentian Library and Michelangelo’s Architectural Method.” Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institute 66 (2003): 29-62.

Hirst, Michael. Michelangelo: The Achievement of Fame. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2011.

Howard, Peter. “Preaching Magnificence in Renaissance Florence.” Renaissance Quarterly 61, no. 2 (2008): 325–69.

———. Creating Magnificence in Renaissance Florence. Toronto: Centre for Reformation and Renaissance Studies, 2012.

Humphreys, K. W. The Book Provision of the Medieval Friars, 1215-1400. Amsterdam: Erasmus Booksellers, 1964.

Kibre, Pearl. The Library of Pico della Mirandola. Morningside Heights: Columbia University Press, 1936.

Montecchi, Giorgio and Alberto Calciolari. La biblioteca dei Pico nel palazzo ducale di Mirandola. Il catalogo del 1723. Mirandola: Gruppo Studi Bassa Modenese, 2006.

Mussolin, Mauro. “Michelangelo and the Experience of Space.” In Michelangelo: Divine Draftsman and Designer, edited by Carmen C. Bambach, 273-278. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2017.

Najemy, John M. A History of Florence, 1200-1575. West Sussex: Blackwell Publishing, 2008.

Presciutti, Diana Bullen. “Carità e potere: Representing the Medici Grand Dukes as ‘Fathers of the Innocenti.’” Renaissance Studies 24, no. 2 (2010): 234–59.

Quillen, Carol E. “A Tradition Invented: Petrarch, Augustine, and the Language of Humanism.” Journal of the History of Ideas 53 (1992): 179-207.

Robathan, Dorothy M. “The Catalogues of the Princely and Papal Libraries of the Italian Renaissance.” Transactions and Proceedings of the American Philological Association 64 (1933): 138-149.

Rose, Paul Lawrence. “Humanist Culture and Renaissance Mathematics: The Italian Libraries of the Quattrocento.” Studies in the Renaissance 20 (1973): 46-105.

Salmon, Frank. “The Site of Michelangelo’s Laurentian Library.” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 49/4 (1990): 407-429.

Shearman, John K. G. Mannerism. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1967.

Sherer, Daniel. “Tafuri’s Renaissance: Architecture, Representation, Transgression.” Assemblage 28 (1995): 35–45.

Stine, Darin. “A Reconsideration of Michelangelo’s Unrealised Façade for the Basilica of San Lorenzo in Florence.” Architectural History 62 (2019): 39–67.

Summers, David. Michelangelo and the Language of Art. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1981.

———. “Form and Gender.” New Literary History 24, no. 2 (1993): 243–71.

Sverzellati, Paola. “Per la storia della Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana.” Aevum 86, no. 3 (2012): 969–1004.

Thompson, James Westfall. The Medieval Library. New York and London: Hafner Publishing Company, 1967.

Tolzman, Don Heinrich, Alfred Hessel, and Reuben Peiss. The Memory of Mankind. New Castle: Oak Knoll Press, 2001.

Ullman, Berthold L. and Philip A. Stadter. The Public Library of Renaissance Florence: Niccolo Niccoli, Cosimo de’Medici, and the Library of San Marco. Padua: Editrice Antenore, 1972.

Vasari, Giorgio. Opere di Giorgio Vasari, pittore e architetto aretino. Florence: Presso S. Audin, 1822.

Wallace, William E. Michelangelo at San Lorenzo: The Genius as Entrepreneur. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994.

Wittkower, Rudolf. “Michelangelo’s Biblioteca Laurenziana.” The Art Bulletin 16, no. 2 (1934): 123–218.