The Small-Scale Miners of the Great Mining: Informality and Precariousness in Mina Vieja in Potrerillos (Chile, 1959-1978) ❧

Universidad de Santiago de Chile

Universidad de Santiago de Chile

California State University, Los Angeles, United States

https://doi.org/10.7440/histcrit97.2025.03

Reception: April 3, 2025 / Acceptance: May 26, 2025 / Modification: June 26, 2025

Abstract. Objective/context: Between the late 1950s and 1978, around 400 artisanal miners (pirquineros) occupied and worked the abandoned Potrerillos mine, known as Mina Vieja (Old Mine). Located on the margins of the territory of a large mining company—first Andes Copper (a subsidiary of Anaconda) and then Cobresal (part of the state-owned company Codelco)—these miners attempted to build an autonomous community by recovering an abandoned and degraded site. Methodology: Based on archival sources and newspapers, this study examines the working and living conditions, along with the risks and safety concerns affecting the community, as well as the development of cooperatives to address production problems. Originality: This article challenges traditional views of the enclave and emphasizs the importance of analyzing the different forms of mining production and how they overlap in the same space. Conclusions: The case of Mina Vieja illustrates the complex relationship between large-scale and small-scale artisanal mining during a period of profound economic, social, and political transformation.

Keywords: artisanal miners, Chile, cooperatives, copper mining, enclaves, history of mining, Popular Unity.

Los pirquineros de la Gran Minería: informalidad y precarización en la Mina Vieja de Potrerillos (Chile, 1959-1978)

Resumen. Objetivo/contexto: entre fines de los años cincuenta y 1978, cerca de cuatrocientos mineros artesanales (pirquineros) ocuparon y trabajaron el mineral abandonado de Potrerillos, conocido como la Mina Vieja. Ubicados en los márgenes del territorio de una gran empresa minera, primero Andes Copper (subsidiaria de Anaconda) y luego Cobresal (parte de la empresa estatal Codelco), los pirquineros intentaron construir una comunidad autónoma a partir de la recuperación de un espacio abandonado y en ruinas. Metodología: sobre la base de fuentes de archivo y periódicos, se analizan las formas de trabajar y habitar, los riesgos y problemas de seguridad que siempre afectaron a la comunidad y la formación de cooperativas para resolver los problemas de producción. Originalidad: este artículo cuestiona las visiones tradicionales de enclave y argumenta la importancia de analizar en conjunto las distintas formas de producción minera y la manera en que estas se sobreponen en un mismo espacio. Conclusiones: el caso de la Mina Vieja muestra las complejas relaciones entre la gran y la pequeña minería artesanal en una época de profundos cambios económicos, sociales y políticos.

Palabras clave: Chile, cooperativas, enclave, historia de la minería, minería del cobre, pirquineros, Unidad Popular.

Os pirquineros na grande mineração: informalidade e precarização na Mina Vieja de Potrerillos. Chile, 1959-1978

Resumo. Objetivo/contexto: Entre o final da década de 1950 e 1978, cerca de 400 mineiros artesanais (pirquineros) ocuparam e trabalharam na mina abandonada de Potrerillos, conhecida como Mina Vieja. Localizados às margens do território de uma grande mineradora, primeiro a Andes Copper (subsidiária da Anaconda) e depois a Cobresal (parte da estatal Codelco), os pirquineros tentaram construir uma comunidade autônoma a partir da recuperação de um espaço abandonado e arruinado. Metodologia: Com base em fontes arquivísticas e jornalísticas, são analisadas as formas de trabalhar e habitar, os riscos e problemas de segurança que sempre afetaram a comunidade, e a formação de cooperativas para solucionar problemas de produção. Originalidade: Este artigo questiona as visões tradicionais de enclave e defende a importância de analisar conjuntamente as diferentes formas de produção mineira e a maneira como elas se sobrepõem e se intersectam no mesmo espaço. Conclusões: O caso da Mina Vieja mostra as complexas relações entre a grande mineração e a pequena mineração artesanal em uma época de profundas mudanças econômicas, sociais e políticas.

Palavras-chave: Chile, enclave, cooperativas, história da mineração, mineração de cobre, pirquineros, Unidad Popular.

Introduction

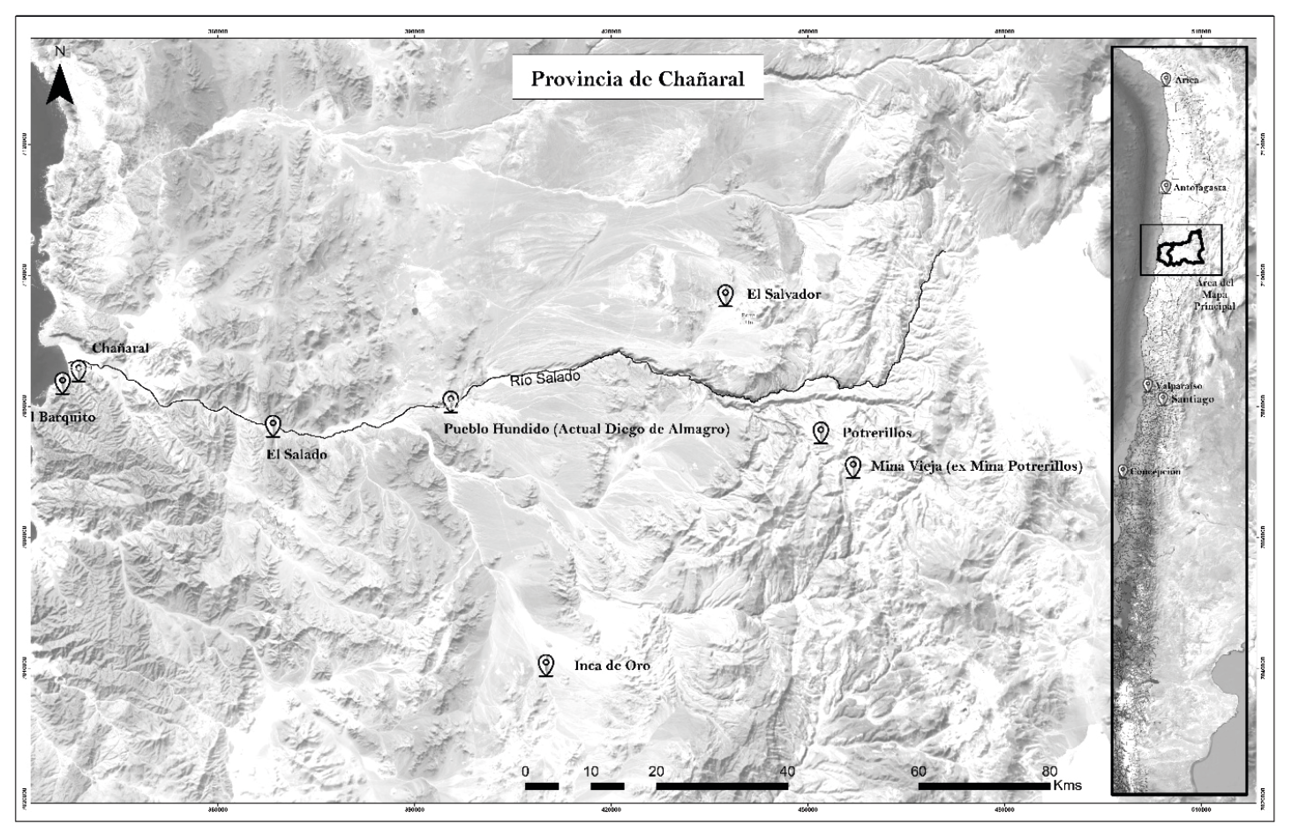

In the early 1960s, roughly 400 small-scale miners and their families settled in the abandoned Potrerillos mine, known as Mina Vieja (Old Mine), in what is now the Chañaral province in the Atacama region (Map 1). The miners who moved to Mina Vieja, called pirquineros in Chile, were part of a long tradition of artisanal work dedicated to the exploitation of low-grade deposits, either independently or through a contractor or facilitator.1 While many valued the independence of pirquinero labor, the lack of social rights and the challenges of entering the commercial circuit created precarious and marginalized conditions. In the case of Mina Vieja, these miners occupied the site for nearly twenty years, sometimes with contracts and other times irregularly, and sought, through cooperatives and a strong social network, to improve their living and working conditions.

The history of Mina Vieja is characterized by the presence of foreign capital, the development of an industrial mining enclave, and cycles of growth and decline, along with population shifts that have shaped Atacama’s history. The modern exploitation of Potrerillos began in the late 1800s when a group of small entrepreneurs attempted to mine copper. Like many small mining firms, they faced major obstacles such as limited capital, technology, and transportation, which were only overcome with the arrival of foreign investment in the early 1900s. As a result, in 1916, a new era began with the formation of a modern company, the Andes Copper Company, and Potrerillos’s integration into the commercial circuits of the global capitalist economy. However, by the mid-1940s, the mine’s depletion was clear, and the company started scaling back operations, a process that culminated in 1959 with the opening of a new mine, El Salvador, and the closure and abandonment of the old mine and its camp.2

Map 1. Chañaral Province, where Mina Vieja is located

Source: Elaborated by Claudio Hahn.

If in the company’s narratives the abandonment of Mina Vieja appears as an anecdotal event, rendered invisible by the optimism created by El Salvador and ongoing activity at the Potrerillos smelter, we argue that this episode is crucial to understanding extractive cycles and their social, economic, and environmental effects. Facing the current ecological crisis, Anna Tsing asks: “What emerges in damaged landscapes, beyond the call of industrial promise and ruin?” In the pine forests of the State of Oregon, which she calls “a ruined industrial landscape,” Tsing finds that not only do the prized matsutake mushrooms grow easily, but also that various groups of people, many originally from Southeast Asia, have settled there and are dedicated to harvesting them.3 While it is true, as the author points out, that ruin opens the door to reclaiming or reimagining a territory and exploring new alternatives for life and production, both the legacies (environmental, material, social) of the industrial cycle and the ongoing transformation of capitalist exploitation and extraction methods limit its future.

Using Tsing’s analytical framework as a starting point and drawing on archival and newspaper sources, this article reconstructs the history of the Potrerillos mine after Andes Copper’s departure in 1959. At the end of the industrial extraction period (1926-1959), the Potrerillos mine, now called Mina Vieja, stripped of its valuable resources, lost significance to modern capitalist enterprise and was abandoned. As reported by communist deputy Hugo Robles in 1969, Mina Vieja “is one of the vestiges of the North American company Andes Copper Mining Company.”4 In other words, returning to Tsing’s idea, a ruined industrial landscape. While all public attention focused on building a new industrial area, the mine and the modernist camp of El Salvador, various groups of artisanal workers from impoverished villages in Atacama began to occupy the site. Precarious housing was built on the ruins of the old camp, and in the abandoned mineshafts, these small-scale miners looked for ways to support their families.

First, this article argues that the experiences of pirquineros at Mina Vieja were shaped by a long history of dispossession and destruction caused by large-scale industrial mining in Atacama, a system of exploitation that, as Gabrielle Hecht highlights in the case of South Africa, “treats people and places as waste and wastelands.”5 Conditions at Mina Vieja were always precarious, not only because these small-scale miners lacked the technology, capital, or resources needed for its operation, but mainly because of the legacy of dispossession and industrial abandonment. On one hand, the mine’s dangerous conditions, frequent accidents, poor living conditions, and the post-industrial landscape were all results of the cycle of exploitation and abandonment started by Andes Copper in 1917. On the other hand, large corporations controlled the production, supply, and transportation networks and continued to profit through the leasing system, which increased miners’ economic and productive hardships.

Second, this article argues that despite conditions of exploitation and precariousness, these pirquineros formed a labor community based on shared experiences of work, risk, and migration. These bonds of solidarity went beyond the local workplace to include various mining communities in the Atacama region. Labor historiography has recognized the importance of studying working-class communities both within and outside traditional workplaces and understanding, from a local perspective, how the conditions and relationships of production shape social spaces and how communities inhabit and transform these spaces.6 In the case of mining, these experiences were also marked by risk, isolation, the influence of companies on daily life, and the overlap of living and working spaces. At Mina Vieja, the miners and their families formed a working-class community; through labor unions, cooperatives, and various social, sports, and political organizations, they fought to improve living, working, and production conditions. They came to value a landscape that others saw as marginal and dangerous. When authorities tried to close Mina Vieja, its residents argued that it was not only their main source of employment but also their home; thus, they were asserting their right to shape their own future.

More broadly, this article contributes to rethinking the relationship between a foreign enclave (in this case, the Large-Scale Copper Industry7) and its surroundings. In the 1960s, dependency theorists introduced the term “economic enclave” to describe how foreign companies extracted and exported natural resources without establishing ties with the region that hosted them. Over time, historiography has refined the concept, emphasizing social, labor, and political contacts and networks beyond the large company.8 The inclusion of artisanal and precarious operations within the territory of an industrial mining company, as is the case with Mina Vieja, shows how different ways of exploitation and labor arrangements overlap within a mining enclave and reveals the formal and informal connections between the company and its surroundings.9 While in many cases these practices are seen as remnants of proletarianization and modernization processes that eventually fade, cases like Mina Vieja demonstrate that they are inherent to the forms of capitalist exploitation used by the large industrial center.10 As Kieran Gilfoy points out about Las Bambas in the Peruvian Andes, the company tolerates or accepts artisanal exploitation on the outskirts of its operations as a way to reduce conflict and, in doing so, allows such exploitation to “function smoothly.”11

The Vestiges of Andes Copper

Geographical isolation influenced the history of the Potrerillos mine. The deposit is situated 10,662 feet above sea level in the Andes mountain range of what is now the Atacama region, just 75 miles from the Pacific coast. The ore found there is porphyritic copper, with a crescent-shaped geological distribution, and was discovered at a depth of around 1,476 feet.12 Andes Copper, a subsidiary of the Anaconda Copper Company, acquired the exploitation rights to the deposit in 1916. After a complex construction process, the mine began production in 1927. To ensure steady output, the North American company built a mining-industrial port complex, connected by a modern railroad capable of overcoming all the challenges posed by the Andean terrain. Additionally, the exploitation, production, and transportation of copper relied on a housing and labor system that included a network of camps centered in Potrerillos, where the smelter and headquarters were located. However, despite the company’s strict control, its borders always remained permeable, and the camps blended into Atacama’s social landscape, with roads winding through ravines and hills.13

The industrial exploitation system radically transformed the landscape. Andes Copper employed the block caving method, which involves collapsing large sections of the deposit by systematically blasting and breaking away the base. This process caused the land to sink, which is why the mine was located below the camp. Additionally, because there was very little land available for building the town, the earth and rock waste from constructing galleries and tunnels was used as fill, deposited in the ravine.14 The waste was compressed with specialized machinery and became the site for housing and services.

During its peak, the Potrerillos mine attracted investment and created wealth, much of which remained in the hands of foreign capital. However, by the mid-1940s, the mine began to show signs of depletion, and many feared both the mine’s end and the collapse of the entire industrial complex it supported. The discovery of a new deposit, El Salvador, just 37 miles away, sparked a fresh period of prosperity. El Salvador began operations in mid-1959, and at the same time, miners and their families were relocated from the mine to a modernist-style camp that would draw the attention of architects.15 The camp was finally closed in early 1961, when the last families left. At the same time, the buildings were dismantled, except for a few that were kept for the workers of a nearby silica mine.16

The reoccupation process of the now-called Mina Vieja mine and its surrounding areas was part of the survival strategies in the Atacama province. Extractive and agricultural activities were unstable and depended on mineral prices or weather conditions; therefore, populations moved around, living and working temporarily in different mining zones. As part of these cycles of extraction, settlement, and depopulation, in the late 1950s, the governor of Atacama observed that “people were settling in, exploiting the work that was unproductive for the Company because the capital employed was insufficient.”17 According to the governor, these miners worked “independently,” without authorization from Andes Copper, and to avoid detection, they transported the minerals through Cuesta de El Hueso.18 The company always held the exploitation rights to Mina Vieja. Possibly to regularize the situation, prevent disputes, or boost profits, it transferred those rights to Augusto Fuentes Soto in 1963. He was a longtime associate of Andes Copper and a businessman from Pueblo Hundido who had worked on building the El Salvador mine.19

Augusto Fuentes relied on traditional labor arrangements to exploit the mine and came to have nearly 400 small-scale miners working either independently or semi-independently.20 He used the traditional pirquén contract, which involved giving miners the right to exploit a deposit in exchange for a fee or regalía. Conditions varied from one mine to another; while some pirquineros worked independently, others were under the supervision of an administrator or contractor, and all paid a fee calculated based on the total mineral extracted.21 This arrangement—the payment or regalía ranged between 10% and 15% of the delivered production at the Mina Vieja mine—concealed a series of abuses, and despite the state’s efforts to improve the economic conditions of small-scale miners, it remained a form of exploitation. For communist senator Julieta Campusano, regalía “is nothing more than the absorption of the last reserves of the miner’s breath.”22

Like other artisanal miners, the pirquineros worked by hand, without mechanized tools, winches, conveyor belts, lathes, or small mills.23 They went deep into the tunnels and hammered the rock to extract the mineral. As a result, the galleries were shaped irregularly, and the miners carried the rock to the surface in baskets, depositing it on nearby land, also called fields. The grinding was done manually, and the miners selected the rocks based on the amount and quality of copper, known as grade. Their methods relied on long-standing traditions and knowledge passed down through generations. In 1971, Fernando Balmaceda filmed the working conditions at Mina Vieja; his documentary shows the enormous physical effort, lack of tools, and harsh environmental conditions.24

The pirquén contract allowed the entrepreneur to withdraw from the production process, leaving the pirquineros exposed to various hardships. At Mina Vieja, the uncertainty surrounding the legality of the lease agreements worsened the issues, risks, and neglect for both working and living conditions. For instance, Fuentes did not install basic services or offer any technical support related to industrial safety or mining operations. At Mina Vieja, according to Revista Sindical Chilena, “time has gone back many decades. Not even in the last century were minerals mined in the primitive way that is done there.”25 Conditions were poor, and profits were slim. Income depended on the quality and quantity of copper found, but it was not uncommon for times when “miners could not find veins containing the minimum amount of ore required and spent their time ‘running the hill.’ This means that they found no metal, only dirt.”26 All access was managed by Andes Copper, and the lack of transportation options made it difficult and costly for miners to obtain basic supplies and deliver minerals to the purchasing agencies of the National Mining Company (Enami).27

As with other mining operations, Mina Vieja exhibited diverse forms of work, production relations, and dependence, with varying levels of informality. Fuentes not only subleased the mine to independent pirquineros but also employed 25 to 30 workers, most of whom worked in the leaching plant located in the so-called Intermediate sector, 6.8 miles from the mine, with the rest involved in extraction activities. Fuentes also operated a second leaching plant called Santa Hortensia in the town of Pueblo Hundido. According to Anuario de la Minería, Fuentes operated the leaching plants from 1965 to 1971, with a daily capacity to process 80 tons of ore.28 Although the workers were contract workers (not independent pirquineros), abuses were widespread, and there were numerous reports of unpaid wages and illegal charges. For example, La Nación accused him of keeping the number of workers below the legal threshold for forming a union and of obstructing any organizing efforts.29

The social reality and material conditions of the pirquineros at Mina Vieja not only reflected the precariousness of artisanal mining but also the damage caused over decades by the exploitation methods used by Andes Copper. According to representative Manuel Magalhaes, a member of the Radical Party, “they stripped Mina Vieja of all its garments; nothing remained of that camp, except the gaze into the infinity of the enormous crater, which still generously yields what little remains of the red metal.”30 The pirquineros and their families settled in the ruins of the old camp and built shacks from salvaged materials. According to Enami, the “social reality” in the area was “deplorable,” and there was no “camp, checkpoint, polyclinic, grocery store, teachers, water, electricity, sewage, etc.”31 In 1970, the population, including women and children, fluctuated between 800 and 1,000 inhabitants, who “live[d] in subhuman conditions and with great job insecurity.”32 Although efforts were made to keep a primary school open, it stayed abandoned and unstaffed most of the time.

The Risks of Pirquinero Work

Toward the end of the 1960s, Mina Vieja was a working community marked by precariousness, informality, and exploitation, which were common in the work of pirquineros in the Atacama province. Despite efforts to extract the remaining ore and earn enough income to support their families, unsafe working conditions and the degradation caused by Andes Copper threatened to ruin the artisanal miners’ dream.

Across the Atacama province, working and safety conditions were unstable. The most common accidents included cave-ins, mechanical failures, falls into the void, and explosions. The danger of the work was worsened by the lack of inspections and the absence of legal protection for pirquineros. As a 1958 International Labour Office (ilo) report noted, “These mines […] are completely immune to inspection, and the state is therefore deprived of the necessary means to enforce safety and health regulations.”33 A decade later, security services remained inadequate, with one State Mining Service technician for every 17,180 miners on average.34 The lack of transportation also hindered the ability to respond to any emergency. For example, during the 1969 accident described below, Representative Raúl Barrionuevo complained that “the officials from the State Mining Department had to go to the mine in my truck because they did not have any other vehicles.”35

The lack of safety measures was worsened by the absence of legal protections for many small-scale miners. As independent workers, they did not have the protections outlined in the Labor Code, and although they could register with the Social Security Service as independent insured individuals, many chose not to. In 1966, while the Senate was discussing social security reform, Julieta Campusano again highlighted the neglect of pirquineros, whom she described as “orphans of security, with no possibility of a reasonably peaceful old age, forced to work until their bodies gave out, and then to wander, living almost on charity.”36

Not all accidents were fatal, but the risk was part of everyday work and highlighted the dangerous conditions faced by workers in small and medium-sized mining operations. Injuries could cause temporary inability to work or, in more serious cases, permanent disability. According to stats from the Anuario de la Minería, fingers, hands, and legs—key for manual labor—were the most commonly injured body parts in mining activities.37 The experience of being trapped was also part of mining life. Cave-ins were common, and even when workers were in a safe area, shelter, or an air pocket, oxygen levels quickly ran out, and rescue efforts often failed. For example, on November 14, 1968, a cave-in happened at the entrance or mouth of a section of Mina Vieja called Mina Honores, trapping two workers and burying them alive for six hours.38

Historically, workplace accidents also served as opportunities to highlight risks, safety deficiencies, and vulnerabilities in mining operations, and in some cases, to promote state intervention.39 In the National Congress, as Diego Ortúzar stated, “tragedies” became “a subject of debate,” while the press published images of the rescue, the widows, the bodies, and the funerals.40 However, while in the case of large mining complexes the emphasis was on the company’s responsibility, and the solution involved financial compensation for victims and the implementation of technical measures, conditions in small-scale artisanal mining were more complex and revealed the limits of government action.

The accident at the end of June 1969, due to its severity and the political climate of that time, marked a turning point in the history of Mina Vieja.41 On the morning of June 30, a collapse at the entrance of the shaft trapped nine miners in the Ventilador area. For three days, over 400 miners in the area, along with two engineers from the National Mining Service—the state agency responsible for mine safety—and police officers, with material support from Andes Copper, worked tirelessly to rescue the miners. On July 2, four trapped workers were rescued alive, but on the same day, another collapse happened, ultimately burying the five workers who had not yet been rescued. Despite the risk of more collapses, the miners refused to abandon their rescue efforts or leave the area until the bodies of their colleagues were recovered, which did not occur until July 15.42

The accident resulted in the deaths of four miners and one worker, Juan Meneses, who was helping with the rescue efforts.43 The funerals revealed a grieving but united community, with rituals and organizations that sharply contrasted with the image of marginality portrayed by the authorities. The funeral procession was led by Pedro Castillo, a leader of the miners, who carried the flagpole of the Unión Mina sports club, founded by Sergio González, one of the deceased.44 The miners’ remains were sent to their respective hometowns: Salamanca, Varilla in Elqui, and Freirina.

The cave-in at the end of June caused a stir in the Atacama province, and the news reached the national media, sparking discussions in both the Chamber of Deputies and the Senate. The debate focused on the characteristics of artisanal mining and its risks, highlighting the various problems faced by pirquineros and the importance of increasing the government’s involvement. Moreover, the link between miners and the so-called “dispossession” of large-scale foreign capital did not go unnoticed and took on particular significance in the discussions about the Chileanization and nationalization of copper. These interventions were rooted in a long history of interactions between mining communities, labor unions, and political parties.

Julieta Campusano’s statements in the Senate highlight the importance of the Mina Vieja tragedy. She had visited the site many times and was aware of the issues impacting artisanal mining. On July 8, she stated, “Insecurity, lack of respect for human beings, lack of work, the struggle for bread, which we have denounced here so many times, were the causes of this murder.” In her speech, the senator also took the opportunity to condemn the poor living and working conditions and the abuses within the regalía system, advocating for the elimination of the contractor and increased government oversight. For Campusano, the “tragedy” was neither an “isolated incident” nor “a product of chance,” and therefore, the solution involved creating new and better job opportunities, addressing security issues, and most importantly, “developing a truly national and progressive mining policy.”45

In response to the legal abandonment of these small-scale miners, the state took various political and administrative measures. In July, the Chamber of Deputies sent multiple letters to different state agencies: the Ministry of Mining was tasked with investigating the causes of the accident; the Ministry of Health was asked to ensure care for the miners at Potrerillos Hospital; and the Ministry of Housing was requested to find housing for the families of the victims. A pension was also set up for the relatives of those who died, and a discussion even began about the need for the state to take over operations and promote the formation of a cooperative.46 Similarly, two of the surviving pirquineros from the collapse were hired at the Paipote National Smelter in Copiapó. This action aimed to address the harm caused by the accident, reward their efforts, and prevent future risks.47

The accident occurred during a time of intense political, social, and economic change. As we will discuss in the next section, the Chileanization process that began in the mid-1960s started to weaken the influence of foreign companies, while efforts to promote medium- and small-scale mining created new opportunities for the state to expand its role. Although large- and small-scale mining were viewed as separate sectors with different laws and policies, in Atacama, the boundaries became blurred. This was noted by Socialist representative Luis Aguilera in a session where, although the main focus was on the impact of drought in the northern region, he also addressed the issues faced by pirquineros and the lack of protection and planning. For Aguilera, the solution was for “all those abandoned mines, especially Anaconda, to return to the state, so that the state could hand them over to the miners”48; thus, he suggested that not all of Anaconda’s properties were part of the Large-Scale Copper Industry.

On the eve of the Popular Unity (up) victory in 1970, the issues faced by workers at Mina Vieja became more visible and caught the attention of the state and its institutions. Since the 1969 accident, the old Potrerillos mine had been targeted by public officials, mining safety agencies, and political and union leaders in the region, who frequently visited the former mine. However, these public interventions mainly focused on welfare, aiming to promote small-scale mining and address social issues, but they did not regard pirquineros as active social agents or independent producers. This tension between welfare efforts and productive independence would become central to the conflicts during the up years.

The Period of Cooperatives (1969-1978)

Since the mid-1960s, the processes of Chileanization (1969-1971) and the nationalization of the Large-Scale Copper Industry (1971), along with the expansion of Enami and a growing concern about the realities faced by pirquinero workers, had a major impact on the province of Chañaral.49 Its inhabitants were not immune to the debates and political polarization of the era, and many of the local demands for improved living and working conditions, as well as the long-standing conflict with foreign capital, were reflected in the up program. It was a time of significant change, which many, especially the families of small-scale miners and seasonal and informal workers living in the local mining towns, saw as a period of hope and empowerment. This is how Edith, sister of Rafael Araya Villanueva, a small-scale miner and Communist Party activist who is listed among the disappeared detainees in Atacama, recalls: “When the Popular Unity government came to power, there was more social justice [...] it was a happier time.”50

The official response to the problems facing Mina Vieja was embedded in the discourse of the time, but, unlike other small-scale mining projects of those years, its fate had unique aspects stemming from its reliance on the Large-Scale Copper Industry, both in production and in social and political ties, as well as the distinctive characteristics of the ore deposit. Hence, the old Potrerillos mine not only reflected the historical challenges faced by small-scale miners in Atacama, such as access to capital, transportation, and purchasing centers, but also the complex relationship between two conflicting forms of production. Therefore, any solution would require the company’s involvement, as it not only owned the old camp and the deposit but also controlled access and means of transportation. Similarly, the pirquineros themselves and their families, organized into labor unions and cooperatives, put forward a series of demands to Cobresal, hoping that it could address their most urgent issues or serve as a mediator in their negotiations with Enami and other government agencies.

Since the late 1960s, mining cooperatives had become one of the Chilean state’s main responses to the challenges faced by small-scale mining, such as limited technology and capital, high transportation and processing costs, and difficulty accessing markets. During Eduardo Frei Montalva’s presidency (1964-1970), cooperativism also served to address social issues and, along with other institutions like mothers’ centers and neighborhood associations, aimed to organize marginalized communities and improve their economic conditions. With government support and under a new legal framework, the first mining cooperatives were established in the late 1960s, although many of these early efforts mainly involved purchasing inputs, goods, or other necessary services for production.51

Mining cooperatives also found a place in the up program, as they were viewed as a form of worker power and self-management, promoting collective work and addressing the social and economic issues faced by small-scale miners.52 During the first two years of the government, as Eduardo Matta (executive vice president of Enami) told the magazine Punto Final, the number of mining cooperatives increased from 6 to 100 organizations, and from 150 to 3,700 pirquineros. Under the revolutionary government, the magazine concluded, “the cooperative gradually changed the individualistic mentality of pirquineros, who for more than a century worked practically alone, without any prospects.”53 In Atacama, mining cooperatives expanded rapidly from the cooperatives that began exploiting the Salado River tailings to small deposits.

At the Mina Vieja mine, the earliest mentions of the possibility of forming a cooperative appeared in 1969.54 For many, the June 1969 accident was due to negligence by Andes Copper and the contractor/lessee managing the mine, Augusto Fuentes; therefore, addressing the safety issue involved replacing the current leasing system with a cooperative one controlled by Enami. In early December 1970, the Ministry of Mining held a meeting that included company officials, Enami representatives, labor leaders, and local authorities.55 At that time, it was decided to end the contract with Fuentes, form one or more cooperatives under Enami’s supervision, and establish Cobresal as one of the collaborating agents. In the following months—what the authorities called an “interim” period—Enami took over the management of the mine, both technically and administratively.56

In March 1971, Fuentes transferred the Mina Vieja facilities, including the leaching plant, which would be handed over “to the Cooperativa [Unión] when the legal procedures were finalized.” Available sources do not specify when or how these procedures were completed, but the cooperative received an initial loan from Enami of 150,000 escudos to buy a shovel. However, in August 1971, the plant still could not operate normally, as reported by Enami’s provincial engineer, “due to the poor condition of the machinery and plant equipment.” By the end of 1971, a new loan for the same amount was authorized for purchasing machinery and paying daily wages.57 The Libertad Cooperative was formed between late 1971 and 1972, bringing together the small-scale miners, many of whom were members of the labor union called Sindicato Profesional de Mineros Pirquineros de Inca de Oro, Mina Vieja Work Center. However, it is unclear from the sources whether this second cooperative managed to regularize its status and gain legal recognition or if it operated more as “de facto,” which was a common practice in the province of Atacama.58

The nationalization of the Large-Scale Copper Industry in July 1971 and its transfer to the Social Area of the Economy shook the foundations of traditional ways of producing, working, and inhabiting mining spaces.59 To the extent that these changes broke down the walls that characterized the enclave system established by foreign companies, nationalization had a broader impact that extended beyond the camps and intersected with other processes of economic and social transformation originating in sectors with their own histories, experiences, and demands, such as small-scale miners. During those years, Cobresal sought to build a new relationship with its environment, authorities, and local community, and to eliminate a series of exploitative practices, like subcontractors, that had taken hold during the North American period.

Between 1971 and the coup d’état on September 11, 1973, the Mina Vieja community actively fought to improve its working and living conditions, building a stronger relationship with local authorities. In December 1971, Cobresal and the medical staff visited Mina Vieja to listen to their problems and demands. There, the newspaper Andino noted, they met with “representatives from the Mothers’ Center, Neighborhood Councils, the ‘La Unión’ Cooperatives, which include 33 workers primarily from the plant, the Pirquineros Cooperative, and union leaders from Mina Vieja.”60 This extensive list of organizations showcases the richness and diversity of the social and associative fabric of these small-scale miners. While the cooperatives focused on securing legal status, which was still “in progress,” as well as transportation and credit to facilitate production, women fought to obtain medical care and better education.

The formation of the Libertad and La Unión cooperatives did not fully address the technical, transportation, and production cost problems faced by these small-scale miners. A March 1972 report highlighted the “inhumane conditions of exploitation, lack of workplace safety, the way workers live, in housing that is completely lacking in basic hygiene, and promiscuity for children.” The workers also noted that their income and financial compensation were very low and that their sales opportunities were limited.61 That same month, a pirquinero died in a cave-in, prompting Cobresal’s safety director, Hugo Murúa, to emphatically state: “There should be no work here under any circumstances. The hill is completely loose, the miners don’t have sufficient resources to shore it up, and working in these conditions ultimately represents a disregard for death.”62 However, leaving the miners jobless had a significant social cost, and the operations continued without major changes. In October of that year, the vice president of Enami stated that “the area being exploited offers no security for work, as we are operating in the collapsed zone, which is completely broken.”63

Despite poverty and insecurity, the pirquineros formed an active community that reflected the cooperative traditions of the mining world. Therefore, there were significant organizational efforts, ranging from recreational activities to campaigns for improved working conditions and political involvement, which demonstrated the diverse interests of the union’s male workers, youth, and women. The Professional Union of Pirquinero Miners of Inca de Oro was established in 1940, and by 1971, it had 341 members and two branches (Mina Vieja and Inca de Oro).64 The Isabel Riquelme Mothers’ Center was established in the late 1960s and provided a space for women to socialize and connect, while also addressing basic family needs.65 Sports clubs also played a significant role in socializing, and Cobresal teams took part in matches and tournaments. The names of the soccer teams reflected different working areas of Mina Vieja and Inca de Oro (pits), such as Deportivo Ventilador, Silica, Túnel, and Copiapino; there were also women’s teams: Las Lolitas del Hundi and Las Estrellas del Norte. The up also expanded its cultural offerings, with theater, music, and dance groups visiting Potrerillos and Mina Vieja. Mina Vieja was also included in programs originating from Potrerillos and El Salvador, both government-organized and grassroots, such as volunteer work, literacy campaigns, and community supply committees.66

Image 1. Closure of Mina Vieja

Source: Andino, May 20, 1977, 9.

The 1973 coup d’état marked the end of Mina Vieja and the forms of participation that had developed over nearly twenty years. Initially, Mina Vieja’s activities were tolerated, and even Mayor Orlando Gutiérrez promised that “a new stage would begin, one of its dignifying,”67 centered on social programs such as the fight against alcoholism and improvements in medical care and educational services. However, Mina Vieja remained a technically unviable, unsafe, and costly project.68 In January 1978, all Mina Vieja activities were suspended, and its residents were asked to vacate the site.69

The sources do not specify what happened to the cooperatives or their assets, whether they were officially dissolved or never formally established and then disappeared. The union tried unsuccessfully to adjust to the changes in labor laws imposed by the military dictatorship but was eventually dissolved in the early 1980s. What happened to the pirquineros and their families is even more uncertain, as their voices faded with the closure of 1978. Some began leaving shortly after the coup, either out of fear or in search of better job opportunities. Many families likely settled in Pueblo Hundido, now called Diego de Almagro, or moved to larger cities where working and living conditions remained difficult.

Conclusions

Many stories intertwine at Mina Vieja, a kind of microcosm that allowed us to observe the establishment of a mining community and its relationships with large corporations and political authorities. Using Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing’s concept of the damaged landscape as a starting point, we examined how these pirquineros built a functioning community in an abandoned and broken space. The challenging conditions were worsened by the site’s features (a mine exploited industrially and using block caving), the presence of Andes Copper (a subsidiary of Anaconda Copper Company), and the influence of local business contractors.

From the late 1960s until the 1973 military coup, the state’s involvement through both Cobresal and Enami fostered a more fluid relationship with the pirquineros, leading to better living conditions and increased access to social services like medical care and education. A key effort was the creation of production cooperatives, which enabled these small-scale miners to obtain credit and technical assistance. This supported their ongoing efforts to improve their living standards and demonstrated their organizational ability. However, issues related to production and safety remained challenging; accidents continued to occur, and output was always limited.

The history of the pirquineros of Mina Vieja encourages us to rethink the relationship between the Large-Scale Copper Industry and artisanal mining—their methods of production, organization, and work, which have traditionally been viewed as separate. In this case, the pirquineros occupied a territory within the Large-Scale Copper Industry and maintained contact with its workers, technical staff, and authorities. Although the sources did not allow us to precisely determine the origins or career paths of these small-scale miners, some evidence suggests there was a circulation of labor, possibly for political, labor-related reasons (such as layoffs), or personal and family strategies.

Finally, this article emphasizes the importance of examining the social, political, and labor practices and connections of modern pirquinero communities, which reflect the complexity of social relations in productive and extractive spaces. For example, the Mina Vieja community was not excluded from major political processes and sought, through cooperatives, union participation, ties with parliament members, and the formation of social organizations, ways to express their demands and improve living and working conditions. While their stories have often been overshadowed by narratives focusing on more unionized and politically influential actors, we highlight that the pirquineros of Mina Vieja are a crucial part of understanding the history of mining in Chile.

Bibliography

Primary sources

Archives

- Archivo Nacional de la Administración (Arnad), Santiago de Chile, Chile. Fondo Ministerio de Minería. Fondo Dirección del Trabajo, División de Relaciones Laborales.

- Archivo Servicio Nacional de Geología y Minas (Sernageomin), Santiago de Chile, Chile. Carpetas Enami.

Periodical publications

- Andino. Potrerillos, 1961, 1971, 1972, 1974, 1977.

- Anuario de la Minería. Santiago de Chile, 1965.

- Diario de Sesiones del Congreso. Santiago de Chile, 1969.

- La Nación. Santiago de Chile, 1970.

- Las Noticias de Copiapó. Copiapó, 1968-1969.

- Punto Final. Santiago de Chile, 1972.

- Revista Sindical Chilena. Santiago de Chile, 1970.

- Revista Vea. Santiago de Chile, 1969.

Audiovisual material

- Balmaceda Fernando, dir. Descarte de El sueldo de Chile. Documentary, Fondo Universidad Técnica del Estado, Subfondo Departamento de Cine y TV UTE, 1971. https://archivopatrimonial.usach.cl/material-audiovisual/ute-dctv-fil-478-483/

Secondary sources

- Agrupación de Beneficiarios Prais. Historia de los ejecutados políticos y detenidos desaparecidos de Atacama en la dictadura cívico militar de 1973-1990. Concepción: Talleres Sartaña, 2019.

- Baros Mansilla, María Celia. Potrerillos y El Salvador: una historia de pioneros. Santiago de Chile: Corporación Minería y Cultura, 2014.

- Calderón-Seguel, Matías, and Manuel Prieto. “Mining Extractivism, Commodification of Nature and Indigenous Peasantry in the Atacama Desert: The Political Economy of Yareta (Azorella Compacta) in Historical Perspective (1915-1960).” Latin American Perspectives 51, n.o 1 (2024): 184-204. https://doi.org/10.1177/0094582X241238715

- Carrasco, Anita. El abrazo de la Anaconda: crónica de la vida atacameña, minería y agua en los Andes. Santiago de Chile: Pehuén; ciir; Centro de Estudios Interculturales e Indígenas, 2023.

- Cartajena Bakovic, Manuel Francisco. La pequeña minería y las cooperativas mineras. Santiago de Chile: Jurídica, s. f.

- Bonilla, Heraclio. El minero de los Andes. Lima: Instituto de Estudios Peruanos, 1974.

- Cerda Inostroza, René. La lucha por la nacionalización del cobre: organización obrera, cultura paternalista y socialismo. Potrerillos y El Salvador, 1951-1973. Santiago de Chile: Talleres Sartaña, 2022.

- Contreras, Carlos. Mineros y campesinos en Los Andes. Lima: Instituto de Estudios Peruanos, 1988.

- Enami, ed. Chile minero: Enami en la historia de la pequeña y mediana minería chilena. Santiago de Chile: Ocholibros, 2009.

- Gilfoy, Kieran. “Mechanised Pits and Artisanal Tunnels: The Incongruences and Complementarities of Mining Investment in the Peruvian Andes.” Journal of Latin American Studies 54, n.o 4 (2022): 679-703, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022216X22000670

- Godoy Orellana, Milton. “Minería popular y estrategias de supervivencia: pirquineros y pallacos en el Norte Chico, Chile, 1780-1950.” Cuadernos de Historia (Santiago), n.o 45 (2016): 29-62. https://doi.org/10.4067/S0719-12432016000200002

- Grez Toso, Sergio. “El escarpado camino hacia la legislación social: debates, contradicciones y encrucijadas en el movimiento obrero y popular (Chile, 1901-1924).” Cuadernos de Historia, n.o 21 (2001): 119-182.

- Hecht, Gabrielle. Residual Governance: How South Africa Foretells Planetary Futures. Durham: Duke University Press, 2023.

- LeGrand, Catherine. “Historias transnacionales: nuevas interpretaciones de los enclaves en América Latina.” Nómadas 25 (2006), 144-154.

- Lobato, Mirta Zaida, ed. Comunidades, historia local e historia de pueblos: huellas de su formación. Buenos Aires: Prometeo, 2021.

- Mooney, Jadwiga E. Pieper. The Politics of Motherhood: Maternity and Women’s Rights in Twentieth-Century Chile. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2009.

- Ortúzar Rovirosa, Diego Esteban. “La gestion des risques professionnels au Chili (1900-1960). Histoire sociale et politique de la santé ouvrière dans un État minimal.” PhD diss., École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales, Paris, 2023. http://journals.openedition.org/acrh/30159

- Parsons, A. B. The Porphyry Coppers. Nueva York: The American Institute of Mining and Metallurgical Engineers, 1933.

- Tapia Araya, Víctor, and Luis Castro Castro. “Los pueblos libres de Chuquicamata: su origen y su desarrollo en los albores del ciclo de la Gran Minería del Cobre en Chile (1886-1930).” Estudios Atacameños 68 (2022): e4832. https://doi.org/10.22199/issn.0718-1043-2022-0010

- Tsing, Anna Lowenhaupt. The Mushroom at the End of the World: On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2015.

- Venegas Valdebenito, Hernán. “El cooperativismo minero como alternativa de organización social y económica en los años de la revolución: Atacama, 1964-1973.” Tiempo Histórico, n.o 5 (2012): 103-127.

- Venegas Valdebenito, Hernán, and Enzo Andrés Videla Bravo. “Sin patrones. Una experiencia obrera de organización laboral: Mina Bateas, Atacama, Chile, 1969-1973.” Estudios Atacameños 67, (2021): e4434. https://doi.org/10.22199/issn.0718-1043-2021-0031

- Vergara, Ángela. “Company Towns and Peripheral Cities in the Chilean Copper Industry: Potrerillos and Pueblo Hundido, 1917-1940s.” Urban History 30, n.o 3 (2003): 381-400. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0963926804001415

- Vergara, Ángela. Copper Workers, International Business, and Domestic Politics in Cold War Chile. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2008.

- Vilches, Flora, and Héctor Morales. “From Herders to Wage Laborers and Back Again: Engaging with Capitalism in the Atacama Puna Region of Northern Chile.” International Journal of Historical Archaeology 21 (2017): 369-388. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10761-016-0386-x

❧ This article is based on research on mining communities in northern Chile. It was made possible thanks to funding from the internship program at Universidad de Santiago, Chile; the Office of Research, Scholarship, and Creative Activities (rsca) at California State University, Los Angeles; and the Chilean National Agency for Research and Development, Human Capital Subdirectorate, National Doctorate Program, folios: 21240091 and 21221332.

It was translated with funding from the Vice President’s Office for Research and Creation at Universidad de los Andes (Colombia). The article was originally published in Spanish as: Ortiz Morales, Ximena, René Cerda Inostroza, y Ángela Vergara. “Los pirquineros de la Gran Minería: informalidad y precarización en la Mina Vieja de Potrerillos (Chile, 1959-1978)”. Historia Crítica, n.o 97 (2025): 51-71. https://doi.org/10.7440/histcrit97.2025.03

1 Milton Godoy Orellana, “Minería popular y estrategias de supervivencia: pirquineros y pallacos en el Norte Chico, Chile, 1780-1950,” Cuadernos de Historia, n.o 45 (2016).

2 About Potrerillos and Andes Copper, see María Celia Baros Mansilla, Potrerillos y El Salvador: una historia de pioneros (Santiago de Chile: Corporación Minería y Cultura, 2014); René Cerda Inostroza, La lucha por la nacionalización del cobre: organización obrera, cultura paternalista y socialismo. Potrerillos y El Salvador, 1951-1973 (Santiago de Chile: Talleres Sartaña, 2022); Ángela Vergara, Copper Workers, International Business, and Domestic Politics in Cold War Chile (University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2008).

3 Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing, The Mushroom at the End of the World: On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2015), 18.

4 Hugo Robles, Diario de Sesiones del Congreso Nacional, Diputados, July 8, 1969, 1428.

5 Gabrielle Hecht, Residual Governance: How South Africa Foretells Planetary Futures (Durham: Duke University Press, 2023), 31.

6 For a summary of these debates, see Mirta Zaida Lobato, ed., Comunidades, historia local e historia de pueblos: huellas de su formación (Buenos Aires: Prometeo, 2021).

7 The Large-Scale Copper Industry refers to the deposits owned by two large foreign companies that dominated the copper industry in Chile until 1971. These included the properties of Anaconda (Chuquicamata, Potrerillos, and El Salvador) and Kennecott Mining Company (El Teniente).

8 For a summary of these debates, see Catherine LeGrand, “Historias transnacionales: nuevas interpretaciones de los enclaves en América Latina,” Nómadas 25 (2006).

9 On the relationship and conflict between mining enclaves and surrounding communities, see, for example, Víctor Tapia Araya and Luis Castro Castro, “Los pueblos libres de Chuquicamata: su origen y su desarrollo en los albores del ciclo de la Gran Minería del Cobre en Chile (1886-1930),” Estudios Atacameños 68 (2022).

10 There is a significant body of literature on the connection between mining and agricultural and Indigenous communities in the Andean region, including classic studies by Heraclio Bonilla and Carlos Contreras in Peru. This body of work highlights labor and trade relationships, as well as conflicts over natural resources like water and environmental pollution. Heraclio Bonilla, El minero de los Andes (Lima: Instituto de Estudios Peruanos, 1974); Carlos Contreras, Mineros y campesinos en los Andes (Lima: Instituto de Estudios Peruanos, 1988). For the case of Chile, see, for example, Anita Carrasco, El abrazo de la Anaconda: crónica de la vida atacameña, minería y agua en los Andes (Santiago de Chile: Pehuén; ciir; Centro de Estudios Interculturales e Indígenas, 2023); Matías Calderón-Seguel and Manuel Prieto, “Mining Extractivism, Commodification of Nature and Indigenous Peasantry in the Atacama Desert: The Political Economy of Yareta (Azorella Compacta) in Historical Perspective (1915-1960),” Latin American Perspectives 51, n.o 1 (2024); Flora Vilches and Héctor Morales, “From Herders to Wage Laborers and Back Again: Engaging with Capitalism in the Atacama Puna Region of Northern Chile,” International Journal of Historical Archaeology 21 (2017).

11 Kieran Gilfoy, “Mechanised Pits and Artisanal Tunnels: The Incongruences and Complementarities of Mining Investment in the Peruvian Andes,” Journal of Latin American Studies 54, n.o 4 (2022), 682.

12 A. B. Parsons, The Porphyry Coppers (Nueva York: The American Institute of Mining and Metallurgical Engineers, 1933), 320-327.

13 Ángela Vergara, “Company Towns and Peripheral Cities in the Chilean Copper Industry: Potrerillos and Pueblo Hundido, 1917-1940s,” Urban History 30, n.o 3 (2003).

14 “Último reportaje a La Mina,” Andino, January 7, 1961, 1 and 8.

15 Vergara, Copper Workers.

16 “Último reportaje a La Mina.”

17 “Luis Fuente-Alva Zúñiga, intendente de Atacama, carta a subsecretario del Interior,” Copiapó, April 29, 1969, Archivo Nacional de la Administración, Santiago-Chile (Arnad), Ministerio de Minería (mm), 1969, vol. Providencias, 409-643.

18 “Informe jurídico,” Copiapó, April 25, 1969, Arnad, mm, 1969, vol. Providencias, 409-643.

19 Baros Mansilla, Potrerillos, 197-198

20 “Sindicato Profesional de Pirquineros de Inca de Oro a ministro de Minería,” Inca de Oro, February 2, 1969, Arnad, mm, 1970, vol. Providencias, 8-291.

21 Godoy Orellana, “Minería.”

22 Julieta Campusano, Diario de Sesiones del Congreso Nacional, Senadores, June 23, 1965, 453.

23 Empresa Nacional de Minería, Departamento Fomento, Sección Cooperativa, “Informe Comisión Mina Vieja de Potrerillos,” December 1970, Arnad, mm, Oficios, vol. 249.

24 Fernando Balmaceda, dir., Descarte de El sueldo de Chile, documentary, Collection: Universidad Técnica del Estado, Subcollection: Departamento de Cine y TV UTE, 1971.

25 “Mina Vieja: rasguñando el cerro,” Revista Sindical Chilena, December 1970, 32.

26 “Mina Vieja: rasguñando el cerro,” 32.

27 The National Mining Company was created in 1960 through the merger of the Mining Credit Fund and the National Smelter Company. Its aim was to promote the extraction and processing of all types of minerals in the country, including their production, concentration, smelting, refining, and marketing. It reflected efforts to support medium- and small-scale mining in Chile as part of the country’s development policies. Enami, ed., Chile minero: Enami en la historia de la pequeña y mediana minería chilena (Santiago de Chile: Ocholibros, 2009).

28 The Anuario de la Minería first mentions Augusto Fuentes Soto in 1965 as the owner of a leaching plant. He also appears on the list of medium-scale mining entrepreneurs in the Atacama province, living in Pueblo Hundido. The last bulletin to mention him is from 1971. Anuario de la Minería, years 1965-1971.

29 “Acuerdo de Codelco,” La Nación, December 3, 1970, 7.

30 Manuel Magalhaes, Diario de Sesiones del Congreso Nacional, Diputados, June 8, 1969, 1430.

31 “Informe Comisión Mina Vieja Potrerillos,” Empresa Nacional de Minería, Departamento Fomento, Sección Cooperativa. Arnad, mm, Oficios, vol. 249, s/p.

32 “Acuerdo de Codelco,” 7.

33 Oficina Internacional del Trabajo, Programa Ampliado de Asistencia Técnica, “Informe dirigido al gobierno de Chile sobre la seguridad en las minas” (Ginebra: OIT, 1958), 18.

34 Anuario de la Minería, 1968, 39.

35 Raúl Barrionuevo, Diario de Sesiones del Congreso Nacional, Diputados, July 16, 1969, 1884.

36 Julieta Campusano, Diario de Sesiones del Congreso Nacional, Senadores, November 15, 1966, 1399.

37 The issues of Anuario de la Minería from 1962 to 1972 included a section on accident statistics organized by type and size of mining activity.

38 “Derrumbe en la Mina Vieja de Potrerillos,” Las Noticias de Copiapó, November 14, 1968, 5.

39 Sergio Grez Toso, “El escarpado camino hacia la legislación social: debates, contradicciones y encrucijadas en el movimiento obrero y popular (Chile, 1901-1924),” Cuadernos de Historia, n.o 21 (2001).

40 Diego Ortúzar Rovirosa, “La gestion des risques professionnels au Chili (1900-1960). Histoire sociale et politique de la santé ouvrière dans un État minimal” (PhD diss., École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales, Paris, 2023), 371.

41 The 1960s in Chile, like in many other parts of the world, were a crucial decade of social and political activism. The different opposing movements resulted in the election of Salvador Allende in 1970. See, for example, Jorge Magasich, Historia de la Unidad Popular (Santiago de Chile: LOM, 2020).

42 The collapse was reported in “9 obreros pirquineros aterrados en Mina Vieja. Patrulla de rescate trabaja activamente. Pirquineros estarían con vida,” Las Noticias de Copiapó, July 1, 1969, 1; “Nuevo derrumbe en faenas del rescate,” Las Noticias de Copiapó, July 3, 1969, 1. See also “10 mineros atrapados por derrumbe,” La Nación, July 1, 1969, 7.

43 The five deceased individuals were identified as Sergio González Zepeda (21 years old, single), Alejandro Rivera Villarroel (21 years old, married), Pedro Antonio Alvarado Pérez (35 years old, married, with two children), Juan Segundo Meneses Meneses (28 years old, married, with five children), and Juan Varela Ramos (24 years old, married).

44 “El salario del ñeque,” Revista Vea, July 10, 1969, 14-17.

45 Julieta Campusano, Diario de Sesiones del Congreso Nacional, Senadores, July 8, 1969, 907.

46 “Moción de los señores Magalhaes y Robles,” Diario de Sesiones del Congreso Nacional, Diputados, July 8, 1969, 1424-1425; Diario de Sesiones del Congreso Nacional, Diputados, July 15, 1969, 1706; Raúl Barrionuevo, Diario de Sesiones del Congreso Nacional, Diputados, July 16, 1969, 1881.

47 “Los mineros salvados del derrumbe trabajan en Paipote,” Las Noticias de Copiapó, August 4, 1969, 1.

48 Luis Aguilera Báez, Diario de Sesiones del Congreso Nacional, Diputados, July 23, 1969, 2221.

49 In June 1969, following the nationalization agreement with Anaconda Copper Co., the Chilean state took over 51% of Andes Copper, now known as Sociedad Minera El Salvador (Cobresal). The company was fully nationalized in July 1971.

50 Agrupación de Beneficiarios Prais, Historia de los ejecutados políticos y detenidos desaparecidos de Atacama en la dictadura cívico militar de 1973-1990 (Concepción, Chile: Talleres Sartaña, 2019), 201.

51 Manuel Francisco Cartajena Bakovic, La pequeña minería y las cooperativas mineras (Santiago de Chile: Jurídica, s. f.).

52 Hernán Venegas Valdebenito, “El cooperativismo minero como alternativa de organización social y económica en los años de la revolución: Atacama, 1964-1973,” Tiempo Histórico, n.o 5 (2012); Hernán Venegas Valdebenito and Enzo Andrés Videla Bravo, “Sin patrones. Una experiencia obrera de organización laboral: Mina Bateas, Atacama, Chile, 1969-1973,” Estudios Atacameños 67, (2021).

53 “El desarrollo de la pequeña y mediana minería del Cobre. Documento,” Punto Final, January 1972, 8.

54 “Andes Copper mantendrá a los pirquineros de Mina Vieja,” Las Noticias de Copiapó, May 9, 1969, 7.

55 Empresa Nacional de Minería, Departamento Fomento, Sección Cooperativa, “Informe Comisión Mina Vieja Potrerillos,” December 1970, Arnad, mm, Oficios, vol. 249.

56 Empresa Nacional de Minería, Departamento Fomento, Sección Cooperativa, “Informe.”

57 Empresa Nacional de Minería, “Informe del ingeniero provincial de Atacama, Hernán Araya,” August 9, 1971, Archivo Servicio Nacional de Geología y Minas (Sernageomin), Santiago de Chile, Chile, Folder Mina Antigua Potrerillos, n.o 3166.

58 Venegas Valdebenito, “El cooperativismo.”

59 Cerda Inostroza, La lucha.

60 “Poco a poco pirquineros salen de su abandono,” Andino, December 18, 1971, 6-7.

61 “Memorándum y proposición de proyecto presentado por los trabajadores de Cooperativa Libertad, Planta Santa Hortencia, y Cooperativa La Unión,” Pueblo Hundido, August 16, 1972, Arnad, mm, Oficios, vol. 267.

62 “En derrumbe murió pirquinero dirigente y deportista,” Andino, March 18, 1972, 8.

63 “De Eduardo Matta Berger, vicepresidente ejecutivo de Enami, a subsecretario de Minería,” Santiago de Chile, October 27, 1972, Arnad, mm, Oficios, vol. 267.

64 Although the 1971 Board Renewal Act does not specify the number of members at the Mina Vieja workplace, four of the five board members, including union president Evaristo Carmona, belonged to and resided at the former Potrerillos mine. In the June 1972 elections for the Chilean Workers’ Union (cut), the Mina Vieja pirquinero union had 267 registered members, with 195 participating, overwhelmingly voting for the Communist Party—163 votes at the national level and 162 votes regionally. Dirección del Trabajo, Inspección Provincial, Acta de Renovación de Directorio, October 5, 1971, Arnad, Fondo Dirección del Trabajo, División de Relaciones Laborales, Sindicato Inca de Oro; “Las elecciones cut en Cobresal,” Andino, June 2, 1972, 1.

65 Since the late 1960s, mothers’ centers have developed as organizations aimed at empowering working-class women and helping them participate in social and economic changes. Although these groups received some support from the government (and during the 1960s were linked to ideas of popular promotion), in many cases they were taken over by working-class women and reinterpreted, turning them into spaces for action, political engagement, and addressing community issues. For an overview of mothers’ centers, see Jadwiga E. Pieper Mooney, The Politics of Motherhood: Maternity and Women’s Rights in Twentieth-Century Chile (Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2009).

66 References to these organizations and their work often appear in the pages of the Andino newspaper, published by Cobresal.

67 “Una tarea que se cumple: dignificar Mina Vieja,” Andino, April 20, 1974, 8.

68 “Adoptan medidas para proteger a pirquineros,” Andino, May 20, 1977, 9.

69 Rolf Behncke Hernández, “Suspendidas todas las faenas en la Mina Vieja,” Andino, January 28, 1978, 3.

❧

PhD candidate in History at Universidad de Santiago de Chile. Her research interests include the history of artisanal mining and labor history. Her publications include “La política minera neoliberal: aproximaciones a los aspectos jurídicos y políticos de la modernización de la minería durante la dictadura cívico-militar chilena. Chile, 1973-1983,” Perfiles Económicos, n.o 14 (2023), 143-171. xortizmorales@gmail.com, https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3549-785X

PhD candidate in History at Universidad de Santiago de Chile. His research interests include the social and environmental history of copper mining in the Atacama region and the history of football and its relationship to politics. His publications include La lucha por la nacionalización del cobre. Organización obrera, cultura paternalista y socialismo: Potrerillos y El Salvador, 1951-1973, and he is the editor of Fútbol y dictaduras: historias, escritos y reflexiones a 50 años del golpe en Chile (Santiago de Chile: Matecito Amargo Spa, 2024). rene.cerda@usach.cl, https://orcid.org/0009-0001-3846-0198

PhD in History from the University of California, San Diego (United States). Professor in the Department of History at California State University, Los Angeles (United States). Her research interests include the social history of labor, social and labor movements, and mining. Her recent publications include Fighting Unemployment in Twentieth-Century Chile (Pittsburgh: Pittsburgh University Press, 2021) and “Working People under Dictatorship”, in The Pinochet Shock: Radical Economic Change and Life under Dictatorship in Chile, edited by Felipe González and Mounu Prem (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2025). avergar@calstatela.edu, https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9474-7559