1. INTRODUCTION

In the field of constitutional and institutional design, it has been frequently argued that inclusiveness should be considered one of the fundamental elements of any constitution-making process (CMP).

Indeed, several authors have linked inclusive CMPs with several outcomes such as increased legitimacy of the charter produced;1 greater constitutional endurance;2 increased levels of democracy;3 charters with more progressive rights provisions and enhanced rights protection,4 and institutions that aim to protect minorities from majority rule.5

What is understood by inclusiveness? From a procedural perspective, an inclusive CMP is one in which inclusive bodies (such as constituent assemblies or ordinary legislative bodies) and mechanisms (such as referendums) are used to bring up a new constitution, regardless of the democratic conditions surrounding the process. But from a more comprehensive viewpoint, an inclusive CMP is one in which -in addition to the existence of procedurally inclusive bodies- real democratic conditions are present, permitting the existence of effective broad deliberation, decision making, and bottom-up participation. Thus, we can distinguish two levels of inclusiveness: procedural and effective.

In the Latin American region, procedurally inclusive CMPs have been a regular occurrence. Only in the last few decades, several inclusive CMPs have taken place, with the emergence of constituent assemblies (Colombia 1991 and Venezuela 1999), public referendums (Peru 1993 and Bolivia 2009), and bottom-up methods of inclusiveness (Brazil 1988 and Ecuador 2008).

Still, little is known of how effectively inclusive these CMPs have been. Jennifer Widner’s “Constitution Writing & Conflict Resolution,” published in 2005, advanced in this direction by classifying the level of inclusiveness of nearly 200 CMPs that occurred between 1975 and 2000.6 Nevertheless, this work was limited to a relatively short period. It was made up of an inconsistent mix of constitutions from all over the world and only measured procedural inclusiveness. The 2015 study by researchers of the United Nations Development Program, which examined CMPs that occurred around the world from 1947 onwards,7 showed similar shortcomings as Widner’s 2005 work. Eisenstadt, LeVan, and Maboudi went further in their recent book by constructing a “process variable” intended to measure the effective participation levels in the convening, debating, and ratification stages of 144 CMPs between 1974 and 2014.8 However, this research only covered a 40-year period and ignored several of the constitutions promulgated within that time frame. Additionally, the research collapsed both the procedural and democratic aspects into a single variable. Similarly, Abrak Saati distinguished different forms of participation present in CMPs, ranging from false participation to substantial participation, but her research is concentrated on 48 fairly recent processes from all over the world.9 Finally, recent works by Negretto10 and Corrales11 give particular attention to the study of CMPs that took place in Latin America, but while Negretto’s research did not examine the interaction between the procedural rules and the democratic conditions surrounding the processes, Corrales focused his study on how conditions surrounding constituent assemblies have an effect on presidential powers and how that, in turn, affects democracy.

Thus, this study aims to conduct a descriptive analysis of the CMPs that took place in Latin America between 1917 and 2016, from an inclusiveness point of view, and distinguish between two types of inclusiveness: procedural and effective. This distinction will be instrumental in future research when we examine the effect of a CMP’s inclusiveness on different indicators: support for and legitimacy of the charter produced by a given process, constitutional endurance, democracy, and conflict levels in the years following the promulgation of a new charter, and substantive content of the constitution (rights, protection of minorities, executive-legislative distribution of power), among other variables.

In the following sections, we introduce several classification measures to assess the degree of inclusiveness that characterized each of the 108 cases we analyzed, we describe in detail the database we considered, and we show the results of our analyses. Then, we discuss our findings, and finally, we present our conclusions.

2. METHOD

In this section, we present two measures, one to assess the degree of procedural inclusiveness, and a second to assess the degree to which democratic conditions were present during the CMP. Then, we explain how to combine them to arrive at a final appraisal regarding the degree of effective inclusiveness throughout the entire CMP.

2.1. Measuring Procedural Inclusiveness

We considered two factors to measure procedural inclusiveness: inclusiveness during the deliberation phase and inclusiveness during the ratification phase.

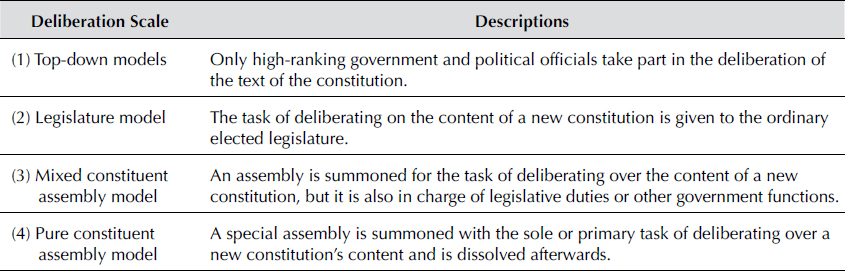

We employed an ordinal classification scale that varies from 1 (least inclusive) to 4 (most inclusive) in reference to the deliberation phase. Thus, rankings were assigned to the different deliberative bodies that have been frequently used in CMPs worldwide.

The array of deliberative bodies considered is based on the one established by Widner,12 with modifications to adapt it to the Latin American historical experience.

A detail of the scale is shown in the diagram below:

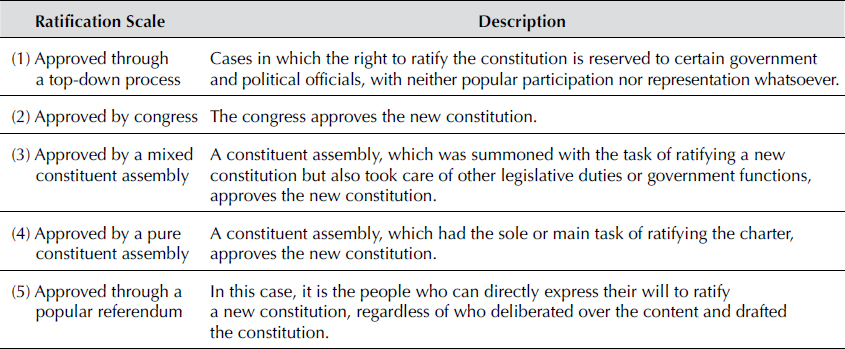

Regarding the ratification phase, we also employed an ordinal classification scale that ranges from 1 (least inclusive) to 5 (most inclusive), which is also loosely based on the distinctions conceptualized by Widner.13

The diagram below presents the five categories of inclusiveness for the ratification phase in detail:

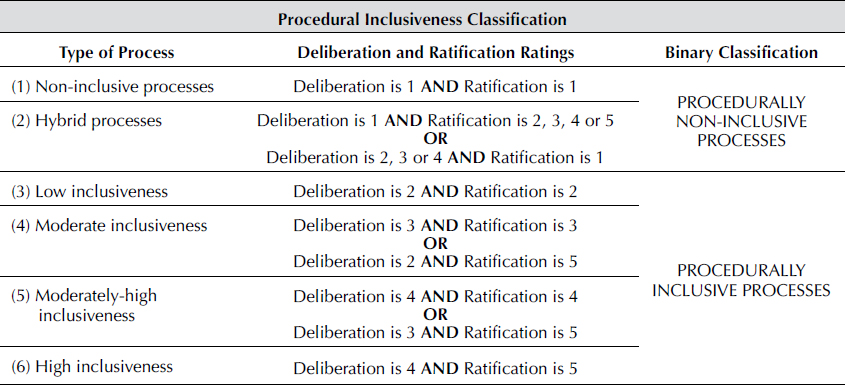

Next, by combining both the deliberation and ratification inclusiveness measures we established an overall ordinal classification of procedural inclusiveness (1 to 6), which allows us to identify different levels of participation. Specifically, processes in which no participatory mechanisms existed, those in which methods of indirect participation existed and, finally, CMPs which counted with direct participatory methods, as seen in the following scheme:

Non-inclusive processes are those that lack any type of popular participation or representation in the constitution-making processes (Cuba 1952 and Guatemala 1982).

Hybrid processes are those that combine inclusive constitution-making phases -either at the deliberative or ratification stage- with non-inclusive ones (for example, when the executive decides on the content of the constitution and then, submits its approval to a public referendum such as in the cases of Haiti in 1964 or Ecuador in 1978).

Processes with low inclusiveness occur when the ordinary legislature is given both the task of deliberating over the content of the new charter and its ratification (Bolivia 1961 and Dominican Republic 2015).

Moderate inclusiveness processes are those in which the deliberative body is a mixed constituent assembly and that same body also has the responsibility of ratifying the constitution (Nicaragua 1987). Cases where the ordinary legislature takes the responsibility of deliberation and then, the ratification is done through a referendum, are also considered moderately inclusive (Uruguay 1952).

Processes with moderately-high inclusiveness happen either when a pure constituent assembly has the task of deliberating over the content of a new charter and that same assembly ratifies it (Colombia 1991), or when a mixed constituent assembly deliberates on the content of the charter and it is then ratified through a referendum (Peru 1993).

Finally, high inclusiveness processes are those in which deliberation is entrusted to a body that has been elected for the sole or main task of producing a new constitution -namely, a pure constituent assembly- and the responsibility of ratifying the charter is given to citizens through a referendum (Haiti 1987 and Venezuela 1999).

Moreover, these six categories can be divided into two general groups: procedurally non-inclusive and procedurally inclusive processes as presented in the diagram above14. These two groups determine the binary Procedural Inclusiveness Indicator.

Note that processes in which constituent assemblies are given deliberative duties have been classified as more inclusive than those in which the regular legislature takes on this responsibility. This is grounded on the fact that, as constituent assemblies have the sole or main responsibility of producing a new charter, it is more likely that, when the population votes for its delegates, they will primarily consider the candidate’s specific constitutional reform proposals instead of broad and general political programs. Therefore, delegates to the constituent assembly will more closely represent the electorate’s view of what a new charter should embody than regular legislators which must try to represent the citizens on countless issues.15

This is also the main reason why processes in which the deliberative body is a pure constituent assembly have been classified as more inclusive than those in which a mixed constituent assembly bears this task.

2.2. Measuring Democratic Conditions

To assess the democratic level of each CMP we developed an index based on eight of the 21 components or sub-indices identified by the “Varieties of Democracy” (V-Dem) research.16 The V-Dem study is part of a project that has examined different aspects of democracy in 201 countries from 1789 to 2017. The eight factors selected represent what we believe are the most relevant elements when it comes to a CMP. The factors considered are:

– Freedom of expression and alternative sources of information index (v2x_free_altinf)

– Freedom of association index (v2x_frassoc_thick).

– Clean elections index (v2xel_frefair).

– Share of population with suffrage index (v2x_suffr)

– Deliberative component index (v2xdl_delib)

– Judicial constraints on the executive index (v2x_jucon).

– Legislative constraints on the executive index (v2xlg_legcon)

– Civil society participation index (v2x_cspart)

Furthermore, in order to account for the democratic conditions present during both the approval stage of the CMP and the deliberative stage, we employed an average of these factors during the year the constitution was enacted and the year prior to that date17.

Each factor is associated with an index that can take values between 0 and 1, in which 0 represents the absence of the condition and 1 represents a full presence of the condition.

Our index of democratic conditions (DemCond Index), which also ranges from 0 to 1, is based on a combination (equal weights) of two aggregate components: The Modified Electoral Democracy Index (MEDI) and the Average High Principle Component Index [AHPCI]. Thus,

Where the MEDI is very similar to the V-Dem Electoral Democracy Index,18 except that it does not include the elected officials’ component (formal-institutional criterion)19 and, the AHPCI is the weighted average of the remaining four sub-indices and intends to take into account the participatory, deliberative, and liberal constitutionalism components that should present in a democratic process.20

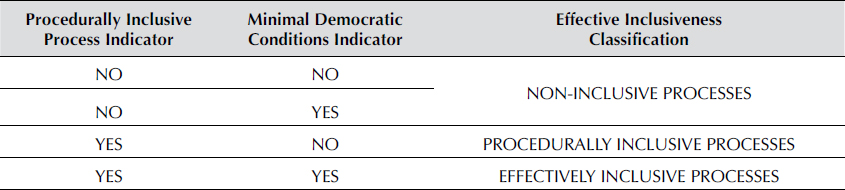

Additionally, following Lindberg,21 we defined a binary Minimal Democratic Conditions Indicator with values equal one (YES) when the DemCond Index was equal or greater than 0.50, and zero (NO) otherwise.22

2.3. Measuring Effective Inclusiveness

Finally, by combining the information provided by the Procedural Inclusiveness Process Indicator and the Minimal Democratic Conditions Indicator we can arrive at an overall assessment of effective inclusiveness using the diagram presented below:

A conceptual characterization of the building blocks behind the Effective Inclusiveness assessment is summarized in the following chart:

3. DATA

The dataset was constructed by the authors relying on a vast array of historical and bibliographical sources, as well as on the constitutional chronology available at the “Comparative Constitutions Project” website.23 The dataset includes every successful CMP of nineteen Latin American countries,24 from 1917 to 2016.

Successful processes are those that formally replaced the existing constitution with a different document, either by the enactment of a completely new constitution, the production of a provisional statute of an interim nature, or by the reinstatement of a previous constitutional text that was no longer in force. In contrast, amendment processes do not replace the existing constitution (at least from a formal perspective), therefore they do not qualify as CMPs and have not been included in the dataset.

With this in mind, we have determined that a constitutional replacement happens every time the document is produced by a process that explicitly states that it is the new basic law, expressly or tacitly abrogating the charter in force up to that moment. While an amendment occurs “…when the actors claim to follow the amending procedure of the existing constitution…”,25 or when new provisions of a constitutional nature are dictated with the expressed intention of complementing or repealing certain parts of the existing charter, but not replacing it completely.

Note that although major reforms to the 1853 constitution have taken place in Argentina in the 20th century,26 we have not included these reforms as new constitutions in our database. Also, following similar criteria, processes that have produced provisional norms that recognize the existence and validity of the constitution (even if, in practice, they replace or abrogate considerable parts of it) have not been included (such as in the case of Brazilian Decree N° 19.398, of November 11th of 1930 or the Statute of the Argentine Revolution of 1966).

Our dataset is made up of 108 Latin American successful CMPs which have taken place since 1917, including five processes that produced constitutional documents of an interim nature and seven that reinstated old constitutions.

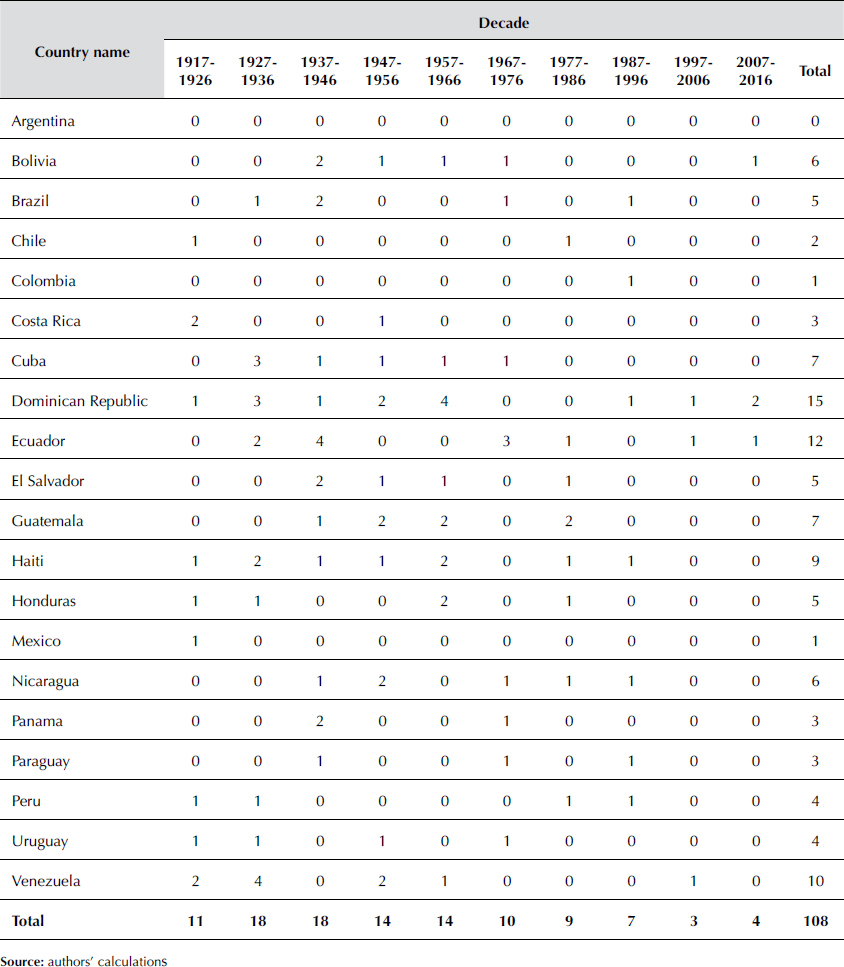

During the 1917-2016 period, constitutions were enacted on a regular basis, with an average of more than one constitution per year. However, the data show that the highest constitutional activity in the region took place in the 1930s and 1940s (Figure 1).

This activity might be explained by the high number of military coups that took place during those years,27 and by the large number of dictatorships that were established in those decades, which tended to sponsor re-foundational projects which were usually enshrined in the form a new charter, as in the case of Brazil in 193728 or Paraguay in 1940.29 While not implying causality, note that in the region, the correlation by decade between the number of constitutions and the number of coups was 0.955.

Also, from a country-by-country perspective, an average of 5.4 constitutions per country were enacted in the last 100 years, with the Dominican Republic, Ecuador, and Venezuela leading the list of constitutional instability in the region, with 15, 12, and 10 constitutional documents promulgated respectively. Alternatively, Colombia, Mexico, and Argentina show the highest constitutional stability, with only one charter decreed in Colombia and Mexico during that time period, and none in Argentina, where the 1853 constitution remains in place, albeit with considerable amendments and modifications (Table 1).

4. RESULTS

4.1. Procedural Inclusiveness

From a purely procedural perspective, the data gathered show that Latin American constitution making processes have tended to be considerably inclusive.

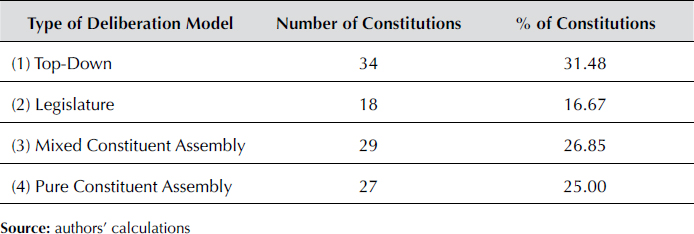

In relation to the deliberative phase, in 68.52% of cases the deliberative body has been inclusive, while top-down processes have occurred in this time frame in only 31.48% of cases (Table 2).

In the ratification phase, the data show that the most common body that has been used to ratify a new constitution has been mixed constituent assemblies (25% of the cases), followed by pure constituent assemblies (23.15%), ordinary congresses (20.37%), and popular referendums (17.59%), while only in 13.89% of cases, the constitution has been approved through top-down mechanisms with no citizen participation (Table 3).

When aggregating both phases, 68.52% of the total number of CMPs have been procedurally inclusive. In detail, 5.56% of the processes qualify as highly inclusive, 21.30% as moderately-high inclusive, 26.85% as moderately inclusive, and 14.81% as lowly inclusive.

On the other hand, only 31.48% have been procedurally non-inclusive (17.59% of these being hybrid processes and 13.89% completely non-inclusive). The procedural inclusiveness of Latin American CMPs can be seen in Table 4:

From a time evolution perspective, the data show that despite a slight negative slope during the initial decades, there has been a consistent increase in the procedural inclusiveness of processes from 1987 to 2016 (Figures 2 and 3). This relationship, while non-linear in nature, was significant at p<0.05.

4.2. Democratic Conditions

In stark contrast to the procedural aspect, the data for the democratic conditions under which the CMPs took place are appalling: only 15 out of the total of 108 processes took place under minimal democratic conditions; in other words, less than 14% of the total CMPs.

Notwithstanding this shocking statistic, it is interesting to note that from a time perspective, -just as in the case with procedural inclusiveness- conditions under which CMPs took place have improved starting in the late 1980’s (Figure 4). Also, the percentage of CMPs that complied with minimal democratic conditions has increased significantly over time, in particular during the last 30 years (Table 5).

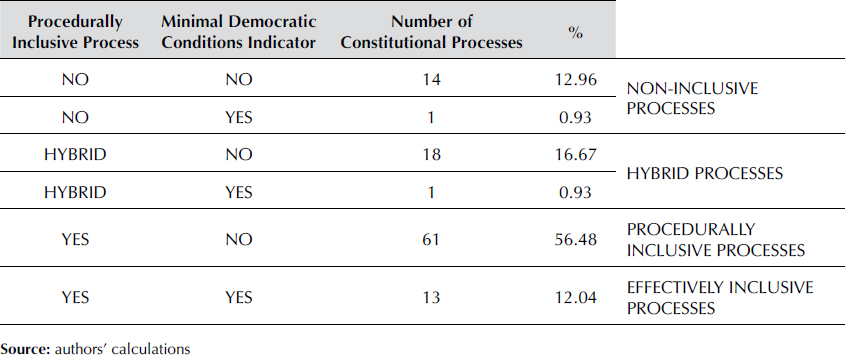

4.3. Procedurally and Effectively Inclusive Processes

The analysis of the procedural inclusiveness of the constitutional processes in conjunction with the democratic conditions prevailing at the time that each CMP took place shows that just 13 of 108 CMPs (roughly 12%) can be classified as effectively inclusive processes as, not only did they follow procedurally inclusive methods, but also allowed for effective participation of the polity in the making of the new charter. On the other hand, 61 processes (56.48%) included procedurally inclusive methods but were deficient in democratic conditions. Additionally, about 31.48% of the CMPs were categorized as non-inclusive (34 processes), despite the fact that two of these processes occurred under effective democratic conditions (Table 6).

Table 6.

Number and percentage of non-inclusive, procedurally inclusive, and effectively inclusive CMPs since 1917

Although a huge percentage of procedurally inclusive processes occurred under non-democratic conditions (56.48% of the total or 82.43% of procedurally inclusive processes), when dividing procedurally inclusive processes and procedurally non-inclusive processes into the six categories previously explained in section 2, it can be noticed that higher procedural inclusiveness tends to translate (albeit not always) into a higher average democratic index. Also, it seems that in most cases, as the degree of procedural inclusiveness increases, a higher percentage of processes comply with minimal democratic conditions. All of this is especially observed in the case of highly inclusive processes (Table 7).

Also, when correlating procedural inclusiveness with democratic conditions, we found a positive correlation (0.23 p<.05). Thus, not implying causation, the analysis indicates a strong association between procedural inclusiveness and effective democratic conditions (Figure 5).

Lastly, analyzing both the procedural and democratic aspects together from a time perspective, both displayed minimal change for many decades (approximately from 1917 until 1987), during which procedural inclusiveness was constantly higher than effective democratic conditions. However, there is a noticeable change from 1987 onwards as, first, procedural inclusiveness increased considerably and, second, it was matched by a similar increase of effective democratic conditions (Figure 6 and Table 8).

5. DISCUSSION

The last 100 years of CMPs in Latin America have been plagued with cases in which procedurally inclusive processes did not go hand in hand with effective democratic and participatory conditions.

As the data shows, cases of faux inclusiveness have been the norm. A paradigm explained by the tendency of non-democratic governments -aiming to coat undemocratic processes with the appearance of legitimacy- to summon seemingly inclusive constitution-making bodies and to opt for procedurally inclusive procedures, while not letting this translate into broad participation, free deliberation, and pluralism of ideas in the making of a new charter.

Such is the case, for example, with the Venezuelan charters written during the dictatorship of Juan Vicente Gómez, who would let the tightly controlled National Congress participate exclusively in the approval phase,30 or with the Dominican constitutions approved under Rafael Trujillo’s rule.31 The same can be said of referendums taking place in sub-par democratic conditions, as in the case of the Haitian 1918 referendum, which took place under military occupation by the United States, and in which the proposed Haitian fundamental law -integrally written by U.S. authorities- was approved by 99.2% of the vote.32

This is reflected in the data as a considerably high percentage of CMPs in Latin America have been inclusive from a procedural aspect (68.52% of the data), but only a fraction of them have also met minimal conditions of democracy and effective participation (barely 13 processes, 12.04% of the total or 17.57% of all procedurally inclusive processes).

Also, just as Table 7 shows, moderate and moderate-high inclusiveness processes have had lower average democracy conditions than low inclusiveness processes. Furthermore, moderate inclusiveness processes display a democratic conditions’ average that is lower than the average of non-inclusive ones. It is also worth noting that hybrid processes show the lowest democratic conditions average.

In any case, the data suggest a relation between higher levels of procedural inclusiveness and higher democratic conditions. The results indicate that a higher level of procedural inclusiveness tends to coincide with higher democratic conditions (Table 7). This is particularly true for highly inclusive processes, which score especially high in democratic conditions.

Regardless of the large number of procedurally inclusive processes that did not comply with minimal democratic conditions, the data also show that although both procedural inclusiveness and effective democratic and participatory conditions in CMPs remained practically the same for about 70 years, from 1987 onwards they increased sharply (Figure 6 and Table 8).

What accounts for this? From 1917 until 1986, every decade saw the existence of a considerable number of authoritarian regimes which, in turn, embarked on authoritarian CMPs. Indeed, this was most certainly the case from the 1910s to the 1940s and continued during the cold war.

In contrast, from 1987 onwards, two groups of CMPs appeared which, for different reasons and at different moments, redefined the scope of citizen participation.

First, the CMPs that took place during the wave of democratization that engulfed Latin America from the late 1970s until the early 1990s.33 Examples of this group of CMPs are the 1988 Brazilian process, which counted with unprecedented levels of public participation;34 the Colombian 1991 CMP in which -in a country in which only two relevant parties had existed throughout history- a diverse group of people and political parties made up the constituent assembly;35 and Ecuador’s 1998 charter which, for the first time, declared Ecuador as pluricultural and multiethnic.36

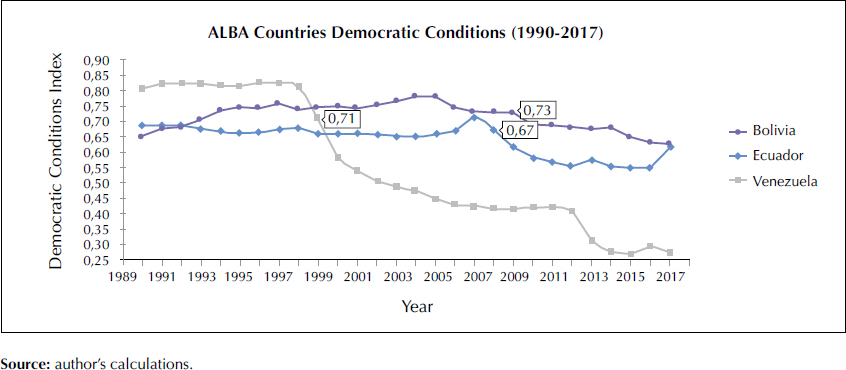

Second, the constituent processes pushed forward by a series of countries that were part of the Bolivarian Alliance for the Peoples of our America (or ALBA for its acronym in Spanish), which aimed to create charters that emphasized social rights and rights of historically excluded groups. In this group, we recognize Venezuela’s 1999, Ecuador’s 2008, and Bolivia’s 2009 CMPs. Note that although these three processes were not only procedurally inclusive but also took place under effective democratic conditions, democracy has been considerably eroded in the years after the enactment of the new constitutions, particularly in the case of Venezuela (Figure 7). Even more, some scholars have suggested that this erosion may have started with the appearance of irregularities during the CMPs themselves.37

6. CONCLUSIONS AND FUTURE RESEARCH

By using a novel and comprehensive dataset that includes every successful CMP that occurred in Latin America between 1917 to 2016, this study has evaluated the inclusiveness of these processes on two levels: procedural and effective. This distinction is key as it provides additional depth when assessing inclusiveness.

A procedurally inclusive CMP is one in which inclusive bodies and mechanisms are used in the making of a new charter (such as constituent assemblies, ordinary legislative bodies, and referendums), regardless of the democratic conditions surrounding the process. Effectively inclusive CMPs are those in which -in addition to the existence of procedurally inclusive bodies- real democratic conditions are present, permitting the existence of effective participation, deliberation, and decision-making.

This distinction is very relevant as scholars have widely argued that inclusiveness is one of the essential elements of any CMP. However, most works on the subject have tended to focus only on the procedural aspect and have neglected to consider the interaction of procedural inclusiveness and the democratic context.

We find that Latin American CMPs have tended to be considerably inclusive from a procedural perspective but only a small number have been effectively inclusive. Thus, a high percentage of procedurally inclusive processes occurred under non-democratic conditions and can be branded as cases of faux inclusiveness. We also find that as the degree of procedural inclusiveness increases, a higher percentage of processes comply with minimal democratic conditions. Finally, we also note that there has been a consistent increase in procedural inclusiveness and democratic conditions of CMPs in the last century, particularly in the last few decades.

These findings open up the possibility of exploring the impact of different levels of CMPs’ inclusiveness on the different aspects of resulting charters. For example: What is the effect that both procedural and effective inclusiveness have on the support, legitimacy, and endurance of the charters? How does the presence of procedural and effective inclusiveness affect the substantive content of a constitution? Do procedurally and effectively inclusive CMPs enhance the quality of democracy in a country? Regarding this last question, the ALBA constitutions presented in the discussion section seem to suggest some preliminary evidence to the contrary, in line with the results of Abrak Saati’s research, which did not find a relationship between participatory CMPs and higher levels of democracy.38 However, further research must be done in order to answer these queries conclusively.