Organic enrichment of sediments from freshwater aquaculture: Preliminary application of the MOM system in a Colombian lake*

Erwann Legrand**

Institute of Marine Research (Norway)

Iván Andrés Sánchez-Ortiz***

Department of Hydrobiological Resources, Universidad de Nariño – Udenar (Colombia)

Pia Kupka Hansen****

Institute of Marine Research (Norway)

Rosa Helena Escobar-Lux*****

Institute of Marine Research, Austevoll Marine Station, Austevoll (Norway)

Naturaleza y Sociedad. Desafíos Medioambientales • número 13 • septiembre-diciembre 2025 • pp. 1-25

https://doi.org/10.53010/nys13.05

Received: May 19, 2025 | Approved: June 26, 2025

Abstract. Aquaculture is steadily expanding and has become a vital source of food and income globally. However, this growth also exerts increasing pressure on aquatic ecosystems. Net-cage aquaculture releases effluents, primarily organic matter, which can cause environmental impacts that vary in severity depending on production intensity and site characteristics. Norway developed the MOM system (Monitoring, Ongrowing fish farms, Modelling) to monitor the environmental impact in marine environments. This study evaluates, for the first time, the MOM system’s applicability to assess the impact of aquaculture in freshwater environments. Sediment samples were collected from Lake La Cocha in Colombia, near three fish farms with different production levels, as well as from two reference sites. The analysis followed the Norwegian MOM protocol, which considers three groups of parameters: the presence/absence of fauna (Group I), pH and redox potential (Group II), and the “sensory” characteristics of the sediments, such as color, odor, and the presence of gas bubbles (Group III). The results indicate that, overall, sediments near the studied farms were in very good to good condition. However, a decrease in pH associated with organic enrichment was observed, along with signs of gas release, reduced sediment consistency, and increased sample volume. These changes suggest sedimentary impacts related to freshwater aquaculture. The results indicate the need for additional measurements and observations of various parameters—including redox potential, color, deposit thickness, and odor—to improve system characterization in continental environments. These findings represent a significant step toward developing an environmental monitoring protocol for freshwater aquaculture. Incorporating data from diverse water bodies and production levels will help refine this protocol and support more sustainable aquaculture development in Colombia.

Keywords: environmental impacts, aquaculture, floating cages, Lake La Cocha, monitoring, organic matter, sediment, Colombia.

Enriquecimiento orgánico de sedimentos de acuicultura continental: aplicación preliminar del sistema MOM en un lago colombiano

Resumen. La acuicultura está en constante expansión y se ha convertido en una fuente vital de alimentos e ingresos a nivel mundial. Sin embargo, este crecimiento también ejerce una presión creciente sobre los ecosistemas acuáticos. La acuicultura en jaulas de red libera efluentes, principalmente materia orgánica, que pueden causar impactos ambientales cuya gravedad varía según la intensidad de la producción y de las características del lugar. Noruega desarrolló el sistema MOM (sigla en inglés de Monitoreo y modelación de la piscicultura mediante jaulas flotantes) para monitorear el impacto ambiental en ambientes marinos. Este estudio evalúa, por primera vez, la aplicabilidad del sistema MOM para determinar el impacto de la acuicultura en ambientes de agua dulce. Se recolectaron muestras de sedimentos del Lago La Cocha en Colombia, cerca de tres piscifactorías con diferentes niveles de producción, así como de dos sitios de referencia. El análisis siguió el protocolo noruego MOM, que considera tres grupos de parámetros: presencia/ausencia de fauna (Grupo I), pH y potencial redox (Grupo II), y las características sensoriales de los sedimentos, como color, olor y presencia de burbujas de gas (Grupo III). Los resultados indican que, en general, los sedimentos cercanos a las piscifactorías estudiadas se encontraban en estado muy bueno a bueno. Sin embargo, se observó una disminución del pH asociada al enriquecimiento orgánico, junto con indicios de liberación de gases, menor consistencia del sedimento y un mayor volumen de muestra. Estos cambios sugieren impactos sedimentarios relacionados con la acuicultura de agua dulce. Los resultados indican la necesidad de realizar mediciones y observaciones adicionales de diversos parámetros, como el potencial redox, el color, el espesor del depósito y el olor, para mejorar la caracterización del sistema en ambientes continentales. Estos hallazgos representan un avance importante en el desarrollo de un protocolo de monitoreo ambiental para la acuicultura de agua dulce. La incorporación de datos de diversos cuerpos de agua y niveles de producción contribuirá al perfeccionamiento de este protocolo y a un desarrollo acuícola más sostenible en Colombia.

Palabras clave: impactos ambientales, acuicultura, jaulas flotantes, Lago La Cocha, monitoreo, materia orgánica, sedimento, Colombia.

Enriquecimento orgânico de sedimentos oriundos da aquicultura de água doce: aplicação preliminar do sistema MOM em um lago colombiano

Resumo. A aquicultura está em constante expansão e tem se tornado uma fonte vital de alimentos e renda em todo o mundo. No entanto, esse crescimento também exerce uma pressão crescente sobre os ecossistemas aquáticos. A aquicultura em tanques-rede libera efluentes, principalmente matéria orgânica, que podem causar impactos ambientais cuja severidade varia conforme a intensidade da produção e as características do local. A Noruega desenvolveu o sistema MOM (Manufacturing Operation Management — modelagem, monitoramento e avaliação ambiental) para acompanhar o impacto ambiental em ambientes marinhos. Este estudo avalia, pela primeira vez, a aplicabilidade do sistema MOM para determinar o impacto da aquicultura em ambientes de água doce. Amostras de sedimentos foram coletadas na Lago La Cocha, na Colômbia, próximas a três pisciculturas com diferentes níveis de produção, bem como em dois locais de referência. A análise seguiu o protocolo norueguês MOM, que considera três grupos de parâmetros: presença/ausência de fauna (Grupo I), pH e potencial redox (Grupo II) e características sensoriais dos sedimentos, como cor, odor e presença de bolhas de gás (Grupo III). Os resultados indicam que, em geral, os sedimentos próximos às pisciculturas estudadas estavam em condições de “boas” a “muito boas”. No entanto, foi observada diminuição no pH associada ao enriquecimento orgânico, juntamente com indícios de liberação de gás, consistência reduzida dos sedimentos e aumento do volume da amostra. Essas mudanças sugerem impactos sedimentares relacionados à aquicultura de água doce. Os resultados indicam a necessidade de medições e observações adicionais de vários parâmetros, como potencial redox, cor, espessura da camada de sedimento e odor, a fim de melhorar a caracterização do sistema em ambientes continentais. Esses achados representam um avanço importante no desenvolvimento de um protocolo de monitoramento ambiental para a aquicultura de água doce. A incorporação de dados de diferentes corpos d’água e níveis de produção contribuirá para o aperfeiçoamento desse protocolo e para um desenvolvimento mais sustentável da aquicultura na Colômbia.

Palavras-chave: impactos ambientais, aquicultura, tanques-rede, Lago La Cocha, monitoramento, matéria orgânica, sedimento, Colômbia.

Introduction

Over the past 30 years, aquaculture has experienced significant growth worldwide. In 2022, the farming of aquatic animals produced 94.4 million tons, accounting for 51% of global aquatic animal production, surpassing capture fisheries for the first time, with a capture of 91 million tons (49%) (FAO, 2024).

Inland aquaculture systems encompass a variety of technologies and intensity levels, ranging from earthen ponds to net cages placed in rivers, lakes, or reservoirs (Beveridge & Brummett, 2015). Aquaculture can also be carried out in net cages in lakes or reservoirs, typically situated in sheltered, nearshore areas (Beveridge, 2004). These net cages are generally framed nets that float on the surface and can be open at the top or fully enclosed and positioned below the water surface.

This production method generates substantial amounts of effluents, including waste feed, feces, nutrients, and by-products like medications and pesticides, if not managed properly (Arshad et al., 2024; Beveridge & Brummett, 2015; Legaspi et al., 2015). Effluent discharges from aquaculture are recognized as a significant pressure on aquatic ecosystems (Arshad et al., 2024; Beveridge & Brummett, 2015). The amount of organic waste entering the lake environment can be substantial, with cage-based production of 1,000 tons of fish potentially releasing between 100 and 600 tons of feed waste per year (Beveridge & Brummett, 2015).

The severity of environmental impacts varies depending on several factors, such as the species being farmed, production levels, feed composition, the environmental characteristics of the farm site (e.g., depth, currents, temperature), and management practices (Beveridge & Brummett, 2015). Compared to marine environments, the environmental impacts of effluents are generally more significant in lakes and reservoirs because of lower water volume, longer retention time, and slower current speeds (Varol, 2019). As a result, the flushing rates and current speeds may be insufficient to prevent the accumulation of waste from fish farms, leading to increased organic matter and nutrient levels in the sediments (Cornel & Whoriskey, 1993; Karakoca & Topcu, 2017; Varol, 2019). The accumulation of organic waste, including uneaten feed, fecal, and excretory matter, can significantly alter benthic macrofauna, sediment chemistry, and the health of caged fish (Alpaslan & Pulatsü, 2008; Cornel & Whoriskey, 1993; Egessa et al., 2018; Varol, 2019).

Colombia is known for its abundant natural water resources, making it an ideal environment for the expansion of aquaculture (FAO, 2025). In recent years, the country’s aquaculture industry has experienced significant growth, driven by its extensive hydrographic network, favorable climate, and the increasing global demand for fish and seafood. Colombian aquaculture primarily focuses on a few non-native species, particularly rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss), white cachama (Piaractus brachypomus), Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus), and Pacific white shrimp (Penaeus vannamei) (FAO, 2025; Osorio et al., 2013; Pérez-Rincón et al., 2017; Souto Cavalli et al., 2021). In 2023, rainbow trout made up about 16% of Colombia’s total aquaculture production (WAS, 2024). Rainbow trout aquaculture is particularly common in floating cage systems due to their relatively low capital requirements, ease of fish harvesting and feeding, and straightforward management (Dirican, 2021). Major production sites for this species include Lake Tota in Boyacá and Lake Guamués, also called Lake La Cocha, in Nariño (Merino et al., 2013).

The rapid expansion of aquaculture in Colombia is also linked to the decline of capture fisheries caused by overexploitation (OECD, 2016). As a result, aquaculture is expected to become the primary driver of fish production in the country in the coming years. However, despite its potential, the aquaculture industry in Colombia faces several challenges, highlighting the need for sustainable management and increased investments in research, technology, and policy development (Leal et al., 2025).

Environmental concerns are increasingly coming to the forefront as aquaculture intensifies. According to Luna-Imbacuan (2011), knowledge about the pollutant characteristics of fish farming and treatment alternatives in Colombia was limited until the early 2010s. The discharge of aquaculture effluents, which are rich in organic matter, nutrients, and suspended solids, can significantly alter the physical, chemical, and biological properties of water bodies, thereby affecting aquatic ecosystems (Burbano-Gallardo et al., 2021; González-Legarda et al., 2022; Lubembe et al., 2024). More recently, in an opinion piece, Nieto (2024) highlighted emerging signs of unsustainability within the sector, emphasizing concerns over the intensive use of resources, water pollution, and ecosystem degradation. Large-scale fish farms generate significant amounts of waste, including uneaten feed, fish excrement, and chemicals for disease control, which further intensifies environmental pressures. Given these challenges, it is essential to monitor the environmental impacts of fish farming, especially in lentic water bodies, as the combined effects of aquaculture and other human activities threaten the stability of these ecosystems. Addressing these concerns through stronger environmental policies, stricter regulation enforcement, and adopting sustainable aquaculture practices will be crucial for ensuring the industry’s long-term viability in Colombia.

In marine environments, the impact of fish farming on surrounding benthic areas mainly results from the sedimentation of food particles and feces beneath and around fish farms (Elvines et al., 2024; Taranger et al., 2015). Over the past few decades, the increase in large-scale, intensive production of Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) has prompted Norway to develop regulatory frameworks to promote a sustainable aquaculture industry (Taranger et al., 2015). A key component of the Norwegian environmental regulation is the MOM (Monitoring, Ongrowing fish farms, Modelling) system, which ensures that the environmental conditions surrounding fish farms do not deteriorate beyond predefined levels (Ervik et al., 1997; Hansen et al., 2001). The MOM serves both as a model and a monitoring program that includes Environmental Quality Standards (EQS) and primarily focuses on the impacts of aquaculture on the benthos. This system enables a close monitoring of the environmental conditions at farmed sites at a relatively low cost (Hansen et al., 2001). The monitoring program includes three types of investigations (A, B, and C) (Hansen et al., 2001): (i) the A-investigation involves a simple measurement of the sedimentation rate of organic material beneath the fish farm; (ii) the B-investigation is conducted in the local impact zone and evaluates three groups of parameters: biological, chemical, and sensory; (iii) the C-investigation examines the structure of the benthic community along a transect drawn from the fish farm toward sedimentation areas to the sensitive parts of the intermediate and regional impact zones.

Although the MOM system was originally developed for marine fish culture in Norway, it is based on a general concept of environmental management. Therefore, there have been several successful efforts to adapt the MOM-B investigation to other marine species, including shellfish (e.g., Ruditapes philippinarum, Haliotis discus hannai, Crassostrea gigas, and Chlamys farreri), seaweed (e.g., Laminaria japonica), and other fish species (e.g., Lateolabrax japonicus). These adaptations have occurred in different regions around the world by modifying specific parameters and methods (Liu et al., 2024; Oh et al., 2015; Zhang et al., 2009; Zhao et al., 2021). While environmental conditions vary between marine and freshwater environments, the environmental impacts of aquaculture production still share key similarities, especially regarding organic matter emissions. This suggests that the MOM-B system could potentially be adapted to monitor the local environmental impact of fish farms in freshwater areas. In this context, the present study aims to describe the first attempt at applying the MOM-B investigation system to freshwater finfish aquaculture in a Colombian lake.

Materials and methods

Site selection

The convergence of the high Andean and Amazon regions creates unique and interconnected ecosystems, which include páramo, high mountains, hills, plains, wetlands, and lakes. The Ramsar Site known as Lake La Cocha (Lago de la Cocha in spanish) covers an area of 40,077 hectares. It is rich in diverse ecosystems and supports a wide variety of species, significant genetic richness, and extensive water resources that feed into the Amazon basin (Botina-Jojoa & Guerrero-Mora, 2021).

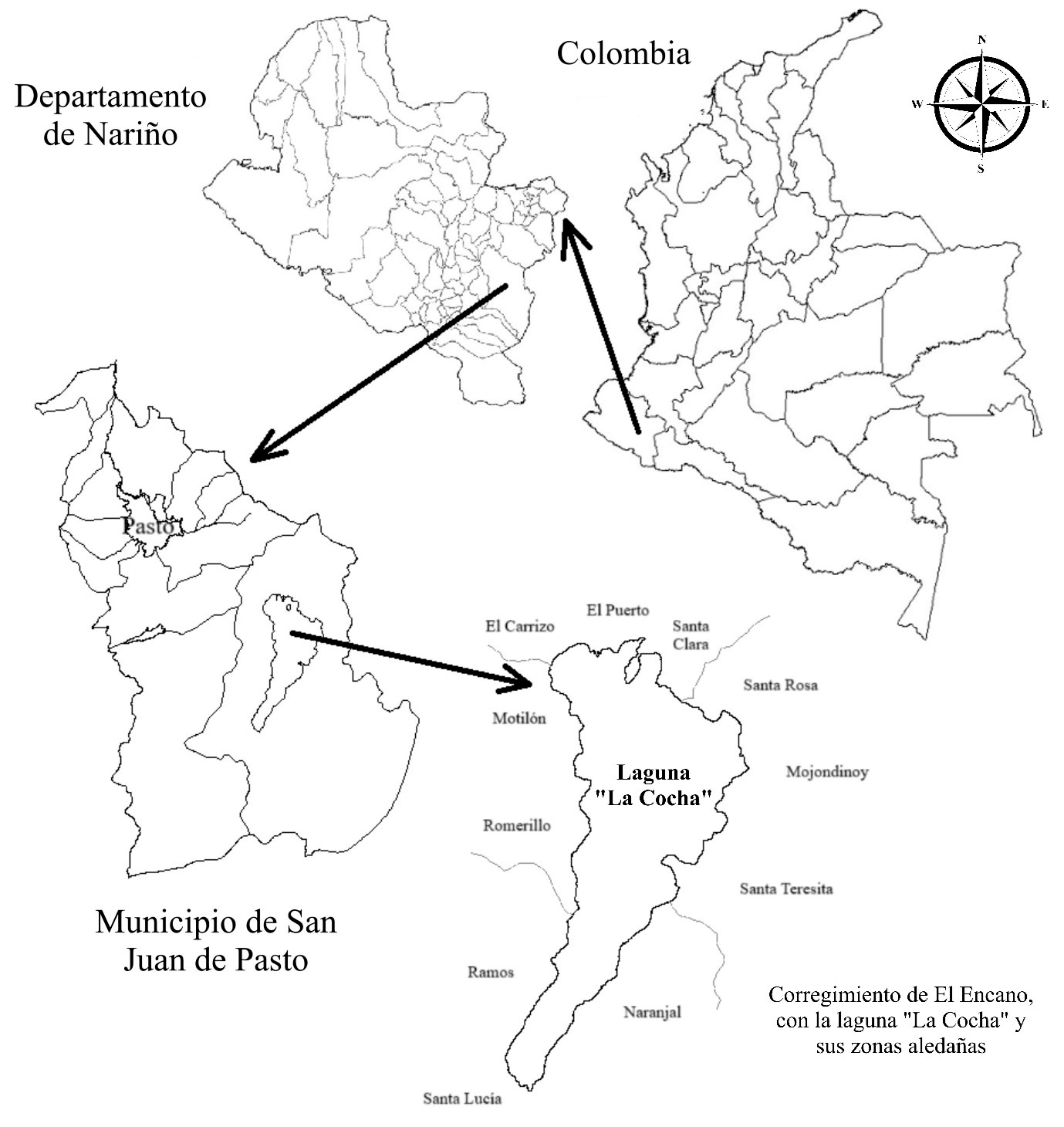

The survey was conducted in Lake La Cocha, located in the department of Nariño between latitudes 0°50’N and 1°15’N and longitudes 77°05’W and 77°20’W, at an average altitude of 2,700 m.a.s.l. (Ministerio de Medio Ambiente, 2001). The lake is located in the El Encano district, east of the municipality of Pasto (Figure 1). Lake La Cocha measures 16 km in length, with a maximum width of 6 km and a maximum depth of 75 m. Its surface area is 42 km2, and it discharges into the Guamuez River (Van Boxel et al., 2013). The lake receives 26 tributaries in a watershed of 225.9 km2, which lies between 2,780 and 3,650 m.a.s.l. (Duque-Trujillo et al., 2016).

Figure 1. Maps showing the location of the study area: Lake La Cocha, Nariño, Colombia.1Source: Own elaboration.

López-Martínez and Madroñero-Palacios (2015) classified Lake La Cocha as an oligotrophic and ultraoligotrophic lake, which is typical of high mountain lakes with low pollution processes of allochthonous and autochthonous origin. However, Bucheli-Rosero et al. (2021) found elevated levels of chlorophyll a in the areas of Mojondinoy, El Naranjal, Santa Teresita, and Santa Lucía, leading them to classify these zones as mesotrophic. The lake undergoes complete mixing in July and September but becomes stratified in May. This pattern is directly influenced by annual fluctuations in rainfall periods: during periods of high rainfall, conditions promote complete mixing, while during low-precipitation periods, thermal stratification takes place. These traits classify it as a warm monomictic lake (López-Martínez et al., 2017). The local environmental characteristics of Lake La Cocha are shown in Table 1.

|

Minimum |

Month of minimum |

Maximum |

Month of maximum |

|

|

Precipitation |

79.2 ± 26.3 mm |

September |

165.8 ± 43.8 mm |

May |

|

Temperature |

10.8 ± 0.4 °C |

August |

12.6 ± 0.3 °C |

November |

|

Evaporation |

50.1 ± 8.8 mm |

June |

68.7 ± 8.3 mm |

November |

|

Relative humidity |

83.7 ± 1.6 % |

November |

87.9 ± 1.5 % |

June |

|

Hydraulic retention time |

6.22 years |

|||

|

Average volume |

1,688 hm³ |

|||

Table 1. Description of the local environmental characteristics of Lake La Cocha, based on data collected between 2004 and 2024 at the El Encano weather station (1°39’35”N, 77°09’41”W; elevation 2,830 m.a.s.l.).Source: Own elaboration.

Sampling and measurements

Sampling

Samples were collected on September 18 and 19, 2024, from two reference sites (usually not included in MOM-B but necessary here for establishing a baseline), located in areas more than 1 km away from any known anthropogenic influence. Additionally, samples were taken directly beneath the cages at three aquaculture farms: Farm A, with the highest production level; Farm B, with medium production; and Farm C, with the lowest production. The production levels of these farms ranged from 7 t to 46 t of fish biomass, and 200 kg to 500 kg of feed used daily. Sampling locations ranged in depth from 5 m (Reference site S2) to 50 m (Reference site S5).

Protocol and equipment

In this survey, the MOM-B investigation was conducted based on the Norwegian Standard NS 9410:2016, which “describes methods for measuring bottom impacts from marine fish farms, and provides detailed procedures for how environmental impacts from individual fish farm sites shall be monitored” (§1. Scope; p. 3). The MOM-B protocol recommends collecting a minimum of 10 samples and a maximum of 20 samples from each fish farm site. However, due to the smaller size of the Colombian fish farms compared to those in Norway, five to eight samples were collected in the present study. Each sample was obtained using a small Van Veen grab (sampling area of 250 cm²) from the net cage floats or from small craft in the immediate vicinity of the fish farm. The grab was equipped with hinged flaps on the top for easy collection.

The MOM-B investigation evaluates three groups of parameters: 1) biological parameters, 2) chemical parameters (pH and redox potential), and 3) sensory parameters (Hansen et al., 2001) (Table 2). Multiple modalities were assessed for each group of parameters, and a score was assigned accordingly (Table 2). The higher the impact observed on the sediments, the higher the score given. Measurements were performed sequentially, starting with Group II parameters, followed by Group III, and ending with Group I parameters, as detailed below.

|

Group of parameters |

Parameter |

Modalities |

Score |

|---|---|---|---|

|

I |

Animals |

Yes |

0 |

|

No |

1 |

||

|

II |

pH |

||

|

Eh (mV) |

|||

|

III |

Outgassing |

No |

0 |

|

Yes |

4 |

||

|

Color |

Pale/grey |

0 |

|

|

Brown/black |

2 |

||

|

Smell |

None |

0 |

|

|

Medium |

2 |

||

|

Strong |

4 |

||

|

Consistency |

Firm |

0 |

|

|

Soft |

2 |

||

|

Loose |

4 |

||

|

Grab volume (v) |

v < ¼ |

0 |

|

|

¼ ≤ v < ¾ |

1 |

||

|

¾ ≤ v |

2 |

||

|

Deposit thickness (t) |

t < 2 cm |

0 |

|

|

2 ≤ t < 8 cm |

1 |

||

|

8 cm ≤ t |

2 |

Table 2. List of parameters, their modalities, and scores used in the MOM-B investigation, as described in the Norwegian Standard NS 9410:2016. Source: Own elaboration.

Group II parameters

The pH and redox potential were measured using a pH electrode (HANNA HI 9813-6 Portable pH/EC/TDS/°C Meter) and redox equipment (Radiometer platinum electrode with a reference electrode Ag/AgCl Red Rod). Before conducting the field survey, the pH and redox electrodes were assembled and calibrated according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The pH electrode was calibrated using buffers with pH levels of 4.0 and 7.0. The pH and redox electrodes were placed in a probe holder to ensure the sensors were at the same level. Electrodes were immersed in freshwater collected at the sampling site and were ready for use once the readings stabilized.

After draining the overlying water, the pH and redox potential (Eh) were measured in the sediment from the grab sample using the top flaps. Once the dredge was brought on board, measurements were taken 1 cm below the sediment surface. For redox measurements, Eh was calculated by adding the half-cell potential of the reference electrode (at the relevant temperature) to the measured value.

The differences in pH and redox potential between fish farms and reference sites were analyzed using a one-way ANOVA. When significant differences were found, a post hoc HSD test was performed. Statistical analyses were conducted using R software (version 4.1.2, R Core Team, 2021). The one-way ANOVA was carried out using the aov function in the stats package. Post hoc tests were performed using the HSD.test function from the agricolae package (Mendiburu, 2023). Significant differences were determined based on an approximate 95% confidence interval.

Group III parameters

After measuring pH and redox levels, the grab was opened, and the sediment was placed in a tray. Sensory assessment of the sediment was performed (Group III), as described in the Norwegian Standard protocol. A summary of these parameters is presented in Table 3.

|

Parameter |

Description |

|

Outgassing |

It indicates anoxic conditions due to anaerobic decomposition and the presence of methane. |

|

Color |

It shows the type of decomposition and accumulation of organic matter. |

|

Smell |

It is associated with the decomposition of fish feces and uneaten feed. |

|

Consistency |

It is related to organic matter content. |

|

Grab volume |

Larger volumes indicate softer sediment, characteristic of more easily degradable organic material. |

|

Deposit thickness |

It measures the thickness of accumulated sediment using a ruler. |

Table 3. Summary description of the Group III parameters of the MOM-B system. The full description is provided in the Norwegian Standard Protocol NS 9410:2016. Source: Own elaboration.

Group I parameters

The sediments placed in the tray were sieved through a 1 mm mesh. The remaining material was analyzed for the presence of animals. Animal presence in the sample was recorded as “0” on the sample form, while their absence was noted as “1.”

Sample score calculation

To address potential subjectivity in scoring, the total of all Group III parameters in a single sample was calculated to avoid overemphasizing individual observations (Hansen et al., 2001). A correction coefficient of 0.22 was applied to estimate the sample condition score for direct comparison of Group III points with those of Group II parameters, as recommended by the Norwegian Standard protocol. The sample condition was then determined based on the score as follows:

- ≤ 1: very good

- > 1 to ≤ 2: good

- > 2 to ≤ 3: poor

- > 3: very poor

Results and discussion

Group I parameters

Our results show the presence of benthic macrofauna in seven out of 23 samples. Macrofauna was absent from four out of the five samples collected from Farm A and from all samples from Farm B. In contrast, microfauna was present in five out of eight samples from Farm C. At the reference sites, it was detected in four out of five samples.

The accumulation of organic matter leads to increased oxygen uptake in the sediments due to enhanced metabolism by aerobic bacteria, which results in anoxic conditions (Pamatmat, 1973; Walker & Snodgrass, 1986). These changes in sediment chemistry are likely to alter the structure of benthic communities around fish farming cages (Braaten, 2007). As a result, macrofaunal communities in marine sediments can serve as good indicators of organic impact (Pearson & Rosenberg, 1978), particularly that caused by fish farms (Kutti et al., 2007; Pearson & Black, 2001; Valdemarsen et al., 2015). In marine environments, the absence of macrofauna may indicate very poor environmental conditions; however, in some cases, this absence can be due to ecological factors related to species-specific tolerance for organic enrichment. Therefore, the MOM system places less emphasis on this parameter compared to chemical (Group II) and sensory (Group III) parameters (Hansen et al., 2001).

In lacustrine environments, changes in macrofaunal community structure have also been observed in sediments related to organic enrichment from aquaculture (Egessa et al., 2018; Rooney & Podemski, 2009). A study conducted in Lake 375, Canada, reported a significant decline in the abundance and taxonomic richness of benthic invertebrates due to organic enrichment from a rainbow trout farm, which occurred after two months of production (Rooney & Podemski, 2009). Although our study shows differences in the presence and absence of macrofauna among the collected samples, no clear link can be established to organic input from the cages.

One of the main benefits of the MOM system, as developed in Norway, is that it avoids laboratory analyses that require expert taxonomic identification, thereby reducing time and costs. However, adding a taxonomic evaluation of benthic macrofauna could improve the protocol’s effectiveness in freshwater settings. For example, identifying easily recognizable key opportunistic species and assigning them a scoring metric could offer valuable ecological insights while keeping the system straightforward and practical.

Group II parameters

The results for Group II parameters showed a pH level ranging from 5.8 (sample S2 from Farm C) to 6.9 (sample S1 from Reference Site 1). Farms A, B, and C exhibited average pH values of 6.2 ± 0.1, 5.9 ± 0.0, and 6.0 ± 0.1, respectively (mean ± standard error). In comparison, the average pH at the reference sites was 6.6 ± 0.1. Significant differences in pH were detected between sites (one-way ANOVA, F = 15.75, p < 0.001), with higher pH values observed at the reference sites compared to farm sites (HSD post hoc test, p < 0.05). Regarding redox potential, the values ranged from +244 mV for the reference sample S2 to +337 mV for the Farm C sample S1. No statistical difference was found between sampling sites in terms of redox potential values (one-way ANOVA, F = 0.12, p = 0.95).

Changes in pH are consistent with the findings of González-Legarda et al. (2022), who sampled water and sediment in Lake La Cocha during both low and high rainfall seasons. The authors compared six areas of the lake, focusing on monitoring points beneath the floating cage farming zone for trout. They reported that in the floating cage area and the upper part of the lake—which is more affected by human activities—dissolved oxygen (DO) and pH were the lowest, while turbidity levels were the highest. Additionally, the analyzed sediments showed higher concentrations of organic matter, nitrogen (N), and phosphorus (P) during both high and low rainfall periods, which could contribute to eutrophication issues in the lake (González-Legarda et al., 2022).

The key redox reactions in natural waters involve the oxidation of organic matter and related reductions, including the reduction of oxygen to water, nitrate to nitrogen gas (N₂), Mn(III/IV) to Mn(II), Fe(III) to Fe(II), sulfate to sulfide, and CO₂ to methane (Sigg, 2000). Most redox reactions in sediments happen under conditions of microbial catalysis, driven by the availability of electron acceptors and the presence of organic matter that acts as a carbon source (Park & Jaffé, 1996; Sigg, 2000). Changes in sediment redox status and pH are known to significantly affect sediment chemistry, notably the solubility of metals and nutrients (Miao et al., 2006; Outridge & Wang, 2015). A study conducted in a freshwater lake in Louisiana showed a strong inverse relationship between sediment pH and Eh, with pH decreasing from 7.06 to 5.68 while sediment Eh increased from −200 to +500 mV (Miao et al., 2006). In the study by Miao et al. (2006), the Eh/pH slope was controlled mainly by the Fe system. However, this slope can vary considerably when redox potential is controlled by other electron acceptors, which may be supplied either through diffusion from the water column or produced within the sediment itself (DeLaune & Smith, 1985; Park & Jaffé, 1996; Patrick & Turner, 1968).

Unlike freshwater sediments, marine sediments contain high sulfate levels, and the diverse microbial communities lead to the production of high sulfide concentrations (Outridge & Wang, 2015). Therefore, both pH and redox potential decrease as sulfate reduction by anaerobic bacteria is stimulated by high rates of organic matter sedimentation (Hansen et al., 2001; Hargrave, 2010). However, a nonlinear relationship between pH and redox potential can be observed at higher pH levels, as sulfate reduction is not the predominant redox couple in oxic sediments (Hargrave, 2010).

When using the MOM-B system in marine environments, the interpretation of Group II parameters is based on a relationship established between pH and redox potential (Hansen et al., 2001). This relationship was derived from pH and redox measurements taken in marine sediments beneath Norwegian aquaculture farms (Schaanning, 1991, 1994; Schaanning & Dragsund, 1993), with pH values ranging from 5.0 to 8.2 and redox potential values between −250 and +450 mV. This relationship is divided into five categories, based on descriptions of organic matter enrichment (Grey, 1981; Pearson & Stanley, 1979). A score of 0, 1, 2, 3, or 5 is assigned to each sample based on the pH/redox values obtained. A score of 0 indicates well-oxygenated sediments with low organic input, conditions that are favorable for the presence of benthic communities (Hansen et al., 2001). Conversely, a score of 5 reflects reduced sediments associated with the production of gases such as methane and characterized by low pH values.

Given these differences between marine and freshwater sediment chemistry, this pH/redox relationship could not be applied in the present study. Therefore, gathering additional sediment data from sites with varying levels of organic enrichment would be useful for assessing the potential relationship between these parameters in freshwater environments and for enabling refinement of the MOM-B system. Furthermore, measuring pH and redox potential at multiple sediment depths would provide deeper insights into their covariation and their relationship with organic enrichment from fish farms.

Group III parameters

Regarding Group III parameters, this study suggests differences in sediment structure between the study sites. Firstly, all reference sites, as well as those from Farm C (lower production), displayed sediments with an overall score below 1, indicating very good condition. In general, these sediments were characterized by the absence of outgassing and smell, a pale brown color, a firm to soft consistency (Figure 2A and 2B), and a grab volume typically between ¼ and ¾. Farm B (intermediate production) had scores below 1 (very good condition) for most samples, except for one collected from the center of the floating cages, which scored 1.32 (good condition). A fermentation smell was detected in one sample, although it was diffuse and quickly dissipated. No outgassing was observed, and the sediments generally exhibited soft consistency (Figure 2C). Most samples occupied more than ¾ of the grab volume. Finally, Farm A showed scores ranging from 1 to 2 for four samples (indicating good condition) and a score below 1 for one sample. Outgassing was observed in three of the five collected samples, while sediment consistency was loose in four samples and soft in one (Figure 2D).

Our findings suggest that some Group III parameters used in the MOM-B system, such as outgassing, sediment consistency, and grab volume, are suitable for monitoring the environmental impact of freshwater fish farms. Sediments exposed to a high input of organic matter from aquaculture occasionally exhibited outgassing, indicating anoxic conditions and the production of gases like methane. Overall, these sediments often had a loose consistency compared to less affected samples, which tended to be soft to firm. Similarly, sediments collected near the farms, where impacts were greater, typically occupied a larger grab volume.

Conversely, the relevance of some Group III parameters of the MOM-B system in lacustrine environments remains less certain and needs further characterization to develop a specific monitoring protocol. This is especially true for sediment color, as there are notable differences in sediment chemistry between marine and freshwater environments. In marine environments, sediment color serves as a reliable indicator of anoxic conditions, where hydrogen sulfide, in conjunction with iron, creates black sediments. However, using this visual approach, our study did not find significant color differences in the sediment samples collected. In freshwater systems, hydrogen sulfide levels in sediments are typically low, and our results suggest the need to adjust the color scale to better capture these variations. For example, some samples displayed distinct black patches (marked with an asterisk in Table 4), possibly indicating localized anoxic conditions. Additionally, some samples collected near the farms, which were exposed to high organic input, showed a darker brown color compared to less impacted sediments. These criteria should be taken into account when refining the methodology for future studies.

Furthermore, the importance of the deposit thickness parameter remains unclear, as no organic deposit layer attributable to the farms was observed in the collected samples. One possible explanation is that the production levels of the studied farms are relatively low compared to Norwegian marine farms, which were the basis for developing the MOM-B system. These marine farms produce significantly higher sedimentation rates, resulting in more noticeable deposits.

Finally, the interpretation of sediment smell should be approached with caution in this study. In marine environments, this parameter is linked to the production of hydrogen sulfide under anoxic conditions, which emits a strong, characteristic smell. In contrast, in freshwater environments, anoxic sediments are mainly linked to methane production, an odorless gas that greatly reduces the usefulness of this parameter. Although a fermentation-like smell was identified in sample S3 from Farm B, it was highly volatile, which made it hard to characterize and standardize.

Therefore, more information is needed to better evaluate the relevance of Group III parameters for creating a monitoring protocol tailored to freshwater environments. This calls for a larger number of observations related to these parameters in sediments exposed to a broader range of organic enrichment levels. Consequently, it would be helpful to continue sampling efforts in reservoirs or freshwater bodies with farms operating at higher production intensities, such as the Betania reservoir and Lake Tota, which cause greater organic enrichment in the surrounding sediments. Any changes to these parameters would also influence the calculation of scores associated with each sample, especially the standardization coefficient of 0.22 used here, which is based on the MOM-B methodology for marine sediments. This adjustment would allow for more precise monitoring of the impact of freshwater fish farms.

Figure 2. Presentation of different types of sediments collected during the study: A. Sample S2 from the reference site shows a light brown color and a firm consistency. B. Sample S7 from Farm C has a light gray color and a firm consistency. C. Sample S4 from Farm B presents a light brown color and a soft consistency. D. Sample S2 from Farm A has a brown color and a loose consistency. Photo credits: the authors.

|

Group param. |

Parameter |

Modalities |

Score Farm A |

Score Farm B |

Score Farm C |

Score Reference Sites |

|||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

S1 |

S2 |

S3 |

S4 |

S5 |

S1 |

S2 |

S3 |

S4 |

S5 |

S1 |

S2 |

S3 |

S4 |

S5 |

S6 |

S7 |

S8 |

S1 |

S2 |

S3 |

S4 |

S5 |

|||

|

Depth (m) |

35 |

35 |

35 |

35 |

35 |

24 |

32 |

27 |

22 |

24 |

14 |

14 |

13 |

15 |

16 |

14 |

12 |

7 |

40 |

5 |

20 |

15 |

50 |

||

|

I |

Animals |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

|

|

II |

pH |

6.1 |

6.1 |

6.1 |

6.3 |

6.5 |

5.9 |

5.9 |

5.9 |

5.9 |

6.0 |

5.9 |

5.8 |

5.8 |

6.1 |

6.2 |

6.0 |

5.9 |

6.2 |

6.9 |

6.4 |

6.8 |

6.4 |

6.4 |

|

|

Eh (mV) |

279 |

293 |

334 |

311 |

315 |

313 |

322 |

315 |

286 |

299 |

337 |

279 |

247 |

324 |

326 |

326 |

270 |

283 |

314 |

244 |

313 |

306 |

332 |

||

|

III |

Outgassing |

No |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|||

|

Yes |

4 |

4 |

4 |

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Color |

Pale/grey |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0* |

0 |

0* |

0 |

0* |

0* |

0* |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0* |

0* |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

|

Dark brown/black |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Smell |

None |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

||

|

Medium |

2 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Strong |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Consistency |

Firm |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

||||||||||||||||||

|

Soft |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

|||||||||||||

|

Loose |

4 |

4 |

4 |

4 |

4 |

||||||||||||||||||||

|

Grab volume (v) |

v < ¼ |

0 |

0 |

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

¼ ≤ v < ¾ |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

||||||||||||

|

¾ ≤ v |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

||||||||||||||||||

|

Deposit thickness (t) |

t < 2 cm |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

|

2 ≤ t < 8 cm |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

8 cm ≤ t |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Sum Group III |

6 |

8 |

8 |

9 |

4 |

1 |

5 |

6 |

4 |

4 |

3 |

3 |

3 |

2 |

3 |

3 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

3 |

3 |

4 |

||

|

Corr. Sum (0.22) |

1.32 |

1.76 |

1.76 |

1.98 |

0.88 |

0.22 |

1 |

1.32 |

0.88 |

0.88 |

0.66 |

0.66 |

0.66 |

0.44 |

0.66 |

0.66 |

0.22 |

0.22 |

0 |

0.22 |

0.66 |

0.66 |

0.88 |

||

Table 4. Results for the different farms (Farm A: high production, Farm B: medium production, Farm C: low production). Source: Own elaboration.Note: The Eh value was given after adding the half-cell potential of the reference electrode (at the relevant temperature) to the measured value. The presence of animals is marked with a “0” and the absence with a “1.” Asterisks (*) indicate sediments with black patches.

Future perspectives

Aquaculture plays a vital role in food production and economic growth, especially in rural areas of Colombia. However, to ensure its long-term sustainability and societal acceptance, its expansion must be supported by strong environmental management practices. Instead of banning aquaculture because of environmental risks, it is important to improve regulatory frameworks and implement monitoring strategies to reduce its impacts while boosting its benefits for livelihoods and food security.

This approach is especially relevant in vulnerable ecosystems, such as high-altitude Andean lakes, where pollution can have long-lasting effects. For example, Lake Tota, located in the eastern part of the Boyacá department—a region heavily impacted by agriculture and aquaculture—faces considerable environmental pressures, including the use of toxic agents. According to Jaramillo-García et al. (2020), pollution in the lake results from a combination of factors, such as monoculture of scallions (long green onions), discharge of untreated domestic and industrial wastewater from the municipalities of Tota, Cuítiva, and Aquitania, livestock activities, and rainbow trout farming. Torres-Barrera and Grandas-Rincón (2017) quantified aquaculture’s impact, estimating that from 2005 to 2016, rainbow trout farming in floating cages contributed approximately 5,063 tons of accumulated waste to Lake Tota, including around 196 tons of nitrogen and 35 tons of phosphorus discharged into the lake.

Additionally, they projected a total of 8,712 tons of accumulated waste by 2020. Although the lake has a large water volume that allows it to withstand certain levels of pollution, the authors recommend reducing waste discharges due to the risk of eutrophication caused by macronutrients and the limited capacity of high-altitude tropical lakes to recycle organic matter in sediments. In Andean lakes, where low temperatures slow down decomposition, the recycling period is longer than in other tropical lakes, which increases the risk of nutrient accumulation and ecological imbalance. These findings highlight the urgent need for better environmental monitoring and management practices.

Tools such as the MOM-B system, developed for adaptive aquaculture in Norway, could provide valuable frameworks in Colombia. By conducting regular sediment and water quality assessments, early warning systems, and spatial planning strategies, it becomes possible to effectively balance environmental protection with the socio-economic benefits of aquaculture. While this study focused on Lake La Cocha, it is essential to expand monitoring efforts to other lakes and water bodies to collect more data for better adaptation of the MOM-B system for freshwater systems. Lake Tota, recognized by the Global Wetlands Network as one of the most endangered ecosystems globally, should be a top priority for sampling and data collection in future studies using the MOM-B system.

Conclusion

The MOM-B system represents a general environmental management concept that can be applied, with minimal modifications, to monitor the impact of marine species production in different regions worldwide (Liu et al., 2024; Oh et al., 2015; Zhang et al., 2009; Zhao et al., 2021). However, applying this concept in its current form to freshwater environments presents greater challenges due to significant differences between these systems (e.g., residence time, trophic state, etc.). This study highlights, for the first time, the potential of the MOM-B system for assessing the environmental impact of aquaculture in freshwater environments. Our findings reveal variations in pH (Group II), outgassing, sediment consistency, and grab volume (Group III) across different sites. These parameters indicate sedimentary changes related to organic enrichment from freshwater finfish aquaculture. However, other parameters, such as redox potential, sediment color, deposit thickness, and smell, require additional measurements and observations to better understand their applicability in freshwater systems. It is also important to take measurements at different times of the year to account for local environmental variations in the lakes throughout the annual cycle.

Given the major differences in sediment chemistry between freshwater and marine environments, it is crucial to adapt the MOM-B methodology to fit the specific conditions of freshwater systems for effective and sustainable aquaculture management. The present study emphasizes the need for further research, particularly to improve our understanding of the relationship between pH and redox potential in lake sediments exposed to different levels of organic enrichment. Future work should also focus on establishing color scales for freshwater sediments and assessing the role of smell as a reliable indicator of anoxia. Finally, it is important to expand observations across a wider range of fish production intensities and freshwater systems, such as the Betania reservoir and Lake Tota, to refine the monitoring framework. This will provide valuable comparative data and help develop stronger monitoring strategies for assessing the environmental sustainability of freshwater aquaculture. Only through a more integrated understanding of aquaculture’s environmental footprint can Colombia create site-specific, evidence-based strategies that promote ecological sustainability without hindering the sector’s potential for rural development.

Acknowledgments

This study was carried out as part of the Fish for Development (FfD) program funded by the Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation (NORAD) (project number 15813; project leader Ragnhild Balsvik). We would like to thank all participants of the course “Environmental monitoring of the impact of aquaculture in net cages,” during which the sampling was performed. We are especially grateful to Miyer Ivan Ceron Muñoz for his invaluable assistance in organizing the field activities.

References

Alpaslan, A., & Pulatsü, S. (2008). The effect of rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss Walbaum, 1792) cage culture on sediment quality in Kesikköprü Reservoir, Turkey. Turkish Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences, 8, 65–70.

Arshad, S., Arshad, S., Afzal, S., & Tasleem, F. (2024). Environmental impact and sustainable practices in aquaculture: A comprehensive review. Haya: The Saudi Journal of Life Sciences, 9(11), 447–454. https://doi.org/10.36348/sjls.2024.v09i11.005

Beveridge, M.C.M. (2004). Cage aquaculture. Oxford: Blackwell.

Beveridge, M.C.M., & Brummett, R.E. (2015). Aquaculture and the environment. In J.F. Craig (Ed.), Freshwater fisheries ecology (pp. 794–803). Wiley. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118394380.ch55

Botina-Jojoa, J. A., & Guerrero-Mora, E. Y. (2021). Aspectos educativos- ambientales respecto al humedal Ramsar – Laguna de La Cocha asociados a los servicios ecosistémicos, desde la ecopedagogía con la comunidad educativa de la básica primaria de la institución educativa El Encano del municipio de Pasto [Master’s thesis, Universidad de Nariño]. https://sired.udenar.edu.co/12606/1/210876.pdf

Braaten, R. 2007. Cage aquaculture and environmental impacts. In A. Bergheim (Ed.), Aquacultural engineering and environment (pp. 49–91). Research Signpost: Kerala.

Bucheli-Rosero, L. A., Rojas-Bastidas, B.F., & Mafla-Chamorro, F. (2021). Monitoreo de la calidad del agua mediante clorofila-a aplicando imágenes satelitales en el Humedal Ramsar, lago Guamués. Ingeniare, 17(31), 21–31. https://doi.org/10.18041/1909-2458/ingeniare.31.8935

Burbano-Gallardo, E., Duque-Nivia, G., Imues-Figueroa, M., Gonzalez-Legarda, E., Delgado-Gómez, M., & Pantoja-Díaz, J. (2021). Efecto de cultivos piscícolas en los sedimentos y la proliferación de comunidades bacterianas nitrificantes en el lago Guamuez, Colombia. Ciencia y Tecnología Agropecuaria, 22(2), e1581. https://doi.org/10.21930/rcta.vol22_num2_art:1581

Cornel, G.E., & Whoriskey, F.G. (1993). The effects of rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) cage culture on the water quality, zooplankton, benthos and sediments of Lac du Passage, Quebec. Aquaculture, 109, 101–117. https://doi.org/10.1016/0044-8486(93)90208-G

DeLaune, R.D., & Smith, C.J. (1985). Release of nutrients and metals following oxidation of freshwater and saline sediment. Journal of Environmental Quality, 14(2), 164–168. https://doi.org/10.2134/jeq1985.00472425001400020002x

Dirican S. (2021). Cage aquaculture in Çamligöze Dam Lake (Sivas-Turkey): Challenges and opportunities. International Journal of Agricultural and Natural Sciences, 14(3), 247–254. https://www.ijans.org/index.php/ijans/article/view/548

Duque-Trujillo, J.F., Hermelin, M., & Toro, G.E. (2016). The Guamuéz (La Cocha) Lake. In M. Hermelin (Ed.), Landscapes and landforms of Colombia. World geomorphological landscapes (pp. 203–210). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-11800-0_17

Egessa, R., Pabire, G.W., & Ocaya, H. (2018). Benthic macroinvertebrate community structure in Napoleon Gulf, Lake Victoria: Effects of cage aquaculture in eutrophic lake. Environmental Monitoring and Assessment, 190(112). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10661-018-6498-5

Elvines, D.M., MacLeod, C.K., Ross, D.J., Hopkins, G.A., & White, C.A. (2024). Fate and effects of fish farm organic waste in marine systems: Advances in understanding using biochemical approaches with implications for environmental management. Reviews in Aquaculture, 16(1), 66–85. https://doi.org/10.1111/raq.12821

Ervik, A., Hansen, P.K., Aure, J., Stigebrandt, A., Johannessen, P., & Jahnsen, T. (1997). Regulating the local environmental impact of intensive marine fish farming I. The concept of the MOM system (Modelling-Ongrowing fish farms-Monitoring). Aquaculture, 158, 85–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0044-8486(97)00186-5

FAO. (2024). The state of world fisheries and aquaculture 2024 – Blue Transformation in action. Rome, Italy. https://doi.org/10.4060/cd0683en

FAO. (2025). Colombia. Text by Salazar Ariza, G. Fisheries and Aquaculture. https://www.fao.org/fishery/en/countrysector/naso_colombia

González-Legarda, E.A., Duque Nivia, G., & Ángel Sánchez, D.I. (2023). Cambios ambientales en agua y sedimentos por acuicultura en jaulas flotantes en el Lago Guamuez, Nariño, Colombia. Acta Agronómica, 71(1), 22–28. https://doi.org/10.15446/acag.v71n1.98924.

Grey, J.S. (1981). The ecology of marine sediments. Cambridge University Press.

Hansen, P.K., Ervik, A., Schaanning, M., Johannessen, P., Aure, J., Jahnsen, T., & Stigebrandt, A. (2001). Regulating the local environmental impact of intensive, marine fish farming II. The monitoring programme of the MOM system Modelling–Ongrowing fish farms–Monitoring. Aquaculture, 194(1-2), 75–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0044-8486(00)00520-2

Hargrave, B.T. (2010). Empirical relationships describing benthic impacts of salmon aquaculture. Aquaculture Environment Interactions, 1, 33–46. https://doi.org/10.3354/aei00005

Jaramillo-García, D.F., Rodríguez-Sosa, N., Salazar-Salazar, M., Hurtado-Montaño, C. A., & Rondón-Lagos, M. (2020). Contaminación del Lago de Tota y modelos biológicos para estudios de genotoxicidad. Ciencia en Desarrollo, 11(2), 65–83. https://doi.org/10.19053/01217488.v11.n2.2020.11467

Karakoca, S., & Topcu, A. (2017). Rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) cage culture: Preliminary observations of surface sediment’s chemical parameters and phosphorus release in Gokcekaya reservoir, Turkey. Journal of Geoscience and Environment Protection, 5, 12–23. https://doi.org/10.4236/gep.2017.54002

Kutti, T., Hansen, P.K., Ervik, A., Høisæter, T., & Johannessen, P. (2007). Effects of organic effluents from a salmon farm on a fjord system. II. Temporal and spatial patterns in infauna community composition. Aquaculture, 262(2-4), 355–366. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aquaculture.2006.10.008

Leal, L.A., Ángel-Ospina, A.C., Ramos, J.A.L., & Machuca-Martínez, F. (2025). Aquaculture sector in Colombia: Uncovering sustainability, transformative potential, and trends through bibliometric and patent analysis. Aquaculture, 598, 742068. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aquaculture.2024.742068

Legaspi, K., Lau, A.Y.A., Jordan, P., Mackay, A., Mcgowan, S., Mcglynn, G., Baldia, S., Papa, R.D., & Taylor, D. (2015). Establishing the impacts of freshwater aquaculture in tropical Asia: the potential role of palaeolimnology. Geography and Environment, 2, 148–163. https://doi.org/10.1002/geo2.13

Liu, Y., Wang, X., Wu, W., & Zhang, J. (2024). Testing the applicability of the Modelling-Ongrowing fish farms-Monitoring B (MOM-B) investigation system for assessing benthic habitat quality in the manila clam Ruditapes philippinarum aquaculture areas. Marine Environmental Research, 198, 106558. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marenvres.2024.106558

López-Martínez, M.L., & Madroñero-Palacios, S.M. (2015). Estado trófico de un lago tropical de alta montaña: caso laguna de La Cocha. Ciencia e Ingeniería Neogranadina, 25(2), pp. 21–42. http://dx.doi.org/10.18359/rcin.1430

López-Martínez, M.L., Jurado-Rosero, G.A., Páez-Montero, I.D., & Madroñero-Palacios, S.M. (2017). Estructura térmica del lago Guamués, un lago tropical de alta montaña. Luna Azul, 44, 94–119. https://doi.org/10.17151/luaz.2017.44.7

Lubembe, S.I., Walumona, J.R., Hyangya, B.L., Kondowe, B.N., Kulimushi, J.D.M., Shamamba, G.A., Kulimushi, A.M., Hounsounou, B.H.R., Mbalassa, M., Masese, F.O. & Masilya, M.P. (2024). Environmental impacts of tilapia fish cage aquaculture on water physico-chemical parameters of Lake Kivu, Democratic Republic of the Congo. Frontiers in Water, 6, 1325967. https://doi.org/10.3389/frwa.2024.1325967

Luna-Imbacuan, M.A. (2011). Efluentes piscícolas: Características contaminantes, impactos y perspectivas de tratamiento. Journal de Ciencia e Ingeniería, 3(1), 12–15. https://jci.uniautonoma.edu.co/2011/2011-2.pdf

Mendiburu, F. de. (2023). agricolae: Statistical Procedures for Agricultural Research. R package version 1.3-7. The Comprehensive R Archive Network. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=agricolae

Merino, M.C., Bonilla, S.P., & Bages, F. (2013). Diagnóstico del estado de la acuicultura en Colombia. Autoridad Nacional de Pesca y Acuicultura – AUNAP. Bogotá.

Miao, S., DeLaune, R.D., & Jugsujinda, A. (2006). Influence of sediment redox conditions on release/solubility of metals and nutrients in a Louisiana Mississippi River deltaic plain freshwater lake. Science of the Total Environment, 371, 334–343. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2006.07.027

Ministerio de Medio Ambiente. (2001). Ficha informativa de los humedales de Ramsar. Laguna de la Cocha. Ramsar Sites Information Service. https://rsis.ramsar.org/RISapp/files/RISrep/CO1047RIS.pdf?language=en

Nieto, J. (2024, September 14). El dilema de la acuicultura en Colombia: ¿Una solución sostenible o una amenaza para el futuro? ANEIA. https://aneia.uniandes.edu.co/el-dilema-de-la-acuicultura-en-colombia-una-solucion-sostenible-o-una-amenaza-para-el-futuro/

Oh, H.T., Jung, R.-H., Cho, Y.S., Hwang, D.W., & Yi, Y.M. (2015). Marine environmental impact assessment of abalone, Haliotis discus hannai, cage farm in Wan-do, Republic of Korea. Ocean Science Journal, 50, 657–667. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12601-015-0060-y

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development [OECD]. (2016). OECD Review of Fisheries: Country Statistics 2015. OECD Publishing. http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/rev_fish_stat_en-2015-en

Osorio A, Wills A, & Muñoz A. (2013). Caracterización de coproductos de la industria del fileteado de tilapia nilótica (Oreochromis niloticus) y trucha arcoíris (Oncorhynchus mykiss) en Colombia. Revista de la Facultad de Medicina Veterinaria y de Zootecnia, 60(3), 182–195. https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=407639237004

Outridge, P., & Wang, F. (2015). The stability of metal profiles in freshwater and marine sediments. In J. Blais, M. Rosen, & J. Smol, (Eds.), Environmental contaminants. Developments in paleoenvironmental research. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-017-9541-8_3

Pamatmat, M.M. (1973). Oxidation of organic matter in sediments. Office of Research and Development, US Environmental Protection Agency.

Park, S.S., & Jaffé, P.R. (1996). Development of a sediment redox potential model for the assessment of postdepositional metal mobility. Ecological Modelling, 91, 169–181. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-3800(95)00188-3

Patrick, W.H. Jr., & Turner, F.T. (1968). Effect of redox potential on manganese transformation in waterlogged soil. Nature, 220(2), 476–478.

Pearson, T.H., & Rosenberg, R. (1978). Macrobenthic succession in relation to organic enrichment and pollution in the marine environment. Oceanography and Marine Biology: An Annual Review, 16, 229–311.

Pearson, T.H., & Stanley, S.O. (1979). Comparative measurement of the redox potential of marine sediments as a rapid means of assessing the effect of organic pollution. Marine Biology, 53, 371–379.

Pearson, T.H., & Black, K.D. (2001). The environmental impact of marine fish cage culture. In K.D. Black (Ed.), Environmental impacts of aquaculture (pp. 1–31). Sheffield: Academic Press.

Pérez-Rincón, M., Hurtado, I., Restrepo, S., Bonilla, S., Calderón, H., & Ramírez, A. (2017). Metodología para la medición de la huella hídrica en la producción de tilapia, cachama y trucha: estudios de caso para el Valle del Cauca (Colombia). Revista Ingeniería y Competitividad, 19(2), 109–120. https://doi.org/10.25100/iyc.v19i2.5298

R Core Team. (2021). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. The Comprehensive R Archive Network. https://cran.r-project.org/doc/manuals/r-release/fullrefman.pdf

Rooney, R., & Podemski, C.L. (2009). Effects of an experimental rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) farm on invertebrate community composition. Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences, 66(11), 1949–1964. https://doi.org/10.1139/F09-130

Schaanning, M.T. (1991). Effects of fish farms on marine sediments. Jordforsk, Report No. 212.409-1. (In Norwegian, abstract in English).

Schaanning, M.T., & Dragsund, E. (1993). Relationship between current and sediment chemistry at fish farm sites. Niva/Oceanor report No. OCN R-93051. Oslo: Norwegian Institute of Water Research.

Schaanning, M.T., (1994). Distribution of sediment properties in coastal areas adjacent to fish farms and evaluation of five locations surveyed in October 1993. Niva report No. 3102. Norwegian Institute of Water Research.

Sigg, L. (2000). Redox Potential Measurements in Natural Waters: Significance, Concepts and Problems. In J. Schüring, H.D. Schulz, W.R. Fischer, J. Böttcher, & W.H.M. Duijnisveld (Eds.), Redox (pp. 1–12). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-662-04080-5_1

Souto Cavalli, L., Blanco Marques, F., Watterson, A., & Ferretto da Rocha, A. (2021). Aquaculture’s role in Latin America and Caribbean and updated data production. Aquaculture Research, 52(9), 4019–4025. https://doi.org/10.1111/are.15247

Taranger, G.L., Karlsen, Ø., Bannister, R.J., Glover, K.A., Husa, V., Karlsbakk, E., Kvamme, B.O., Boxaspen, K.K., Bjørn, P.A., Finstad, B., Madhun, A.S., Morton, H.C., & Svåsand, T. (2015). Risk assessment of the environmental impact of Norwegian Atlantic salmon farming. ICES Journal of Marine Sciences, 72, 997–1021. https://doi.org/10.1093/icesjms/fsu132

Torres-Barrera, N.H., & Grandas-Rincón, I.A. (2017). Estimación de los desperdicios generados por la producción de trucha arcoíris en el lago de Tota, Colombia. Corpoica Ciencia y Tecnología Agropecuaria, 18(2), 247–255. https://doi.org/10.21930/rcta.vol18_num2_art:631

Valdemarsen, T., Hansen, P.K., Ervik, A., & Bannister, R.J. 2015. Impact of deep-water fish farms on benthic macrofauna communities under different hydrodynamic conditions. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 101(2), 776–783. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpolbul.2015.09.036

Van Boxel, J. H., González-Carranza, Z., Hooghiemstra, H., Bierkens, M., & Vélez, M. I. (2013). Reconstructing past precipitation from lake levels and inverse modelling for Andean Lake La Cocha. Journal of Paleolimnology, 51(1), 63–77. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10933-013-9755-1

Varol, M. (2019). Impacts of cage fish farms in a large reservoir on water and sediment chemistry. Environmental Pollution, 252, 1448–1454. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2019.06.090

Walker, R. R., & Snodgrass, W. J. (1986). Model for sediment oxygen demand in lakes. Journal of Environmental Engineering, 112, 25–43. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)0733-9372(1986)112:1(25)

World Aquaculture Society [WAS]. (2024, September 12). Aquaculture in Colombia: Current Affairs in 2024. World Aquaculture Society. https://www.was.org/article/Aquaculture_in_Colombia_Current_Affairs_in_2024.aspx#

Zhang, J., Hansen, P.K., Fang, J., Wang, W., & Jiang, Z. (2009). Assessment of the local environmental impact of intensive marine shellfish and seaweed farming—Application of the MOM system in the Sungo Bay, China. Aquaculture, 287, 304–310. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aquaculture.2008.10.008

Zhao, Y., Zhang, J., Qu, D., Yang, Y., Wu, W., Sun, K., & Liu, Y. (2021). Benthic environmental impact of deep sea cage and traditional cage fish mariculture in Yellow Sea, China. Aquaculture Research, 52, 5022–5033. https://doi.org/10.1111/are.15374

1 The sampling sites are not shown on the map because of confidentiality agreements with the producers who took part in the study.

* This study evaluates, for the first time, the applicability of the MOM system to assess the impact of aquaculture in freshwater environments. This study was conducted in Lake La Cocha on September 18 and 19, 2024, as part of the Fish for Development (FfD) program funded by the Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation (NORAD).

** Erwann Legrand. PhD, Institute of Marine Research, Nordnesgaten 50, Bergen. Research group: Benthic Ecology. Contribution: Design and implementation of the research, data collection, analysis of the results, and writing of the manuscript. The latest two publications: Jardim, V.L., Grall, J., Barros-Barreto, M.B., Bizien, A., Benoit, T., Braga, J.C., Brodie, J., Burel, T., Cabrito, A., Diaz-Pulido, G. et al. (2025). Common Terminology to Unify Research and Conservation of Coralline Algae and the Habitats They Create. Aquatic Conservation-Marine and Freshwater Ecosystems, 35, e70121; Legrand, E., Svensen, Ø., Husa, V., Lelièvre, Y., & Svensen, R. (2025). In Situ Growth Dynamics of the Invasive Ascidian Didemnum vexillum in Norway: Insights from a Two-Year Monitoring Study. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 211, 117440. erwann.legrand@hi.no. ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5224-5227.

*** Iván Andrés Sánchez-Ortiz. PhD, Department of Hydrobiological Resources, Universidad de Nariño – Udenar (Colombia). Contribution: Implementation of the research, data collection, and writing of the manuscript. The latest two publications: Mutumbajoy, A.V., Sánchez-Ortiz, I.A., & Matsumoto, T. (2025). Performance in nitrogen, turbidity and phosphorus removal in a RAS using moving bed settler and membrane aerated biofilm reactor. Aquacultural Engineering, 110, 102547; Vargas-Velez, C.D., Sánchez-Ortiz, I.A. & Masumoto, T. (2025). Recovery of coagulants via acid treatment in potabilization sludges and their reuse in raw and urban wastewaters. Water Science & Technology, 91, 1010. ivansaor@hotmail.com. ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7579-5969.

**** Pia Kupka Hansen. PhD, Institute of Marine Research, Nordnesgaten 50, Bergen (Norway). Research group: Benthic Ecology. Contribution: design of the research and writing of the manuscript. Latest two publications: Fang, J., Samuelsen, O. B., Strand, Ø., Hansen, P. K. & Jansen, H. (2020). The effects of teflubenzuron on mortality, physiology and accumulation in Capitella sp. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety, 203, 111029; Zhang, J., Hansen, P. K., Wu, W., Liu, Y., Zhao, Y. & Li, Y. Sediment-focused environmental impact of long-term large-scale marine bivalve and seaweed farming in Sungo Bay, China. Aquaculture, 528, 735561. piakupkahansen1@gmail.com. ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6501-6060

***** Rosa Helena Escobar-Lux. PhD, Institute of Marine Research, Nordnesgaten, Austevoll Marine Station, Austevoll (Norway). Research group: Benthic Ecology. Contribution: Design and implementation of the research, data collection, analysis of the results, and writing of the manuscript. The latest two publications: Zhang, S., Xie, Y., Zeng, C., Fang, J., Perrichon, P. Y. M. T. J., Lux, R. H. E., Tong, R., & Zhang, X. (2025). Synergistic physicochemical-microbial coupling of ultrafine oyster shell powder for enhanced sediment remediation. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 220, 118380; Parsons, A. E., Escobar-Lux, R. H., Hannisdal, R., Agnalt, A. L., & Samuelsen, O. B. (2025). Anti-Sea Lice Veterinary Medicinal Products on Salmon Farms: A Review and Analysis of Their Usage Patterns, Environmental Fate and Hazard Potential. Reviews in Aquaculture, 17(2), e13006. rosa.escobar@hi.no. ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2465-823X.