Gender Semantics and Historical Feminisms: An Interdisciplinary Approach through Natural Language Processing✽

Laura Manrique-Gómez, Tony Montes, and Rubén Manrique

Received: December 1, 2024 | Accepted: May 5, 2025 | Modified: June 3, 2025

https://doi.org/10.7440/res93.2025.02

Abstract| This article explores the evolution of gender semantics in 19th-century Latin America, focusing on the semantic nuances of the word women. The study’s primary aim is to present the results of an interdisciplinary methodology that reveals historical gender concepts embedded in language, analyzed through the dual lens of social sciences and artificial intelligence. This study uses Machine Learning techniques to analyze historical texts, specifically employing Natural Language Processing to detect semantic shifts, part-of-speech tagging, and named entity recognition to identify key gender vocabulary. Additionally, an n-gram approach was employed to recognize the most frequent terms associated with target words. The methodology was applied to a self-collected historical corpus from Latin American Spanish newspapers, demonstrating the effectiveness of these technologies in processing extensive collections of written sources. The article reveals how artificial intelligence tools can elucidate underlying gender ideas in historical written texts, offering empirical insights into the historical inequalities in linguistic representation. By comparing the newspaper dataset results with a specific literary work, the Colombian novel Manuela by Eugenio Díaz Castro (1859), the research highlights latent feminist tensions and revolutionary ideas contesting societal norms. The article does not provide a definitive historical or literary analysis. Instead, it invites social scientists to engage in the next phase of research by illustrating the potential of artificial intelligence in enhancing interpretability and critical analysis of historical narratives through interdisciplinary collaboration. This article contributes to historical feminist debates by presenting an original framework synthesizing qualitative and computational methods, open datasets, and code, thus expanding the possibilities of traditional historiography. It concludes with reflections on improving gender semantic studies, emphasizing how this integration of disciplines can propel future research directions in critical cultural inquiries.

Keywords | artificial intelligence; gender semantics; historical feminisms; machine learning; natural language processing; 19th-century Latin America

Semántica de género y feminismos históricos: un enfoque interdisciplinario desde el procesamiento de lenguaje natural

Resumen | Este artículo estudia la evolución de la semántica de género durante el siglo XIX en América Latina, con especial énfasis en los matices de la palabra mujer. El objetivo principal es presentar los resultados de una metodología interdisciplinaria que, a partir de un análisis dual desde las ciencias sociales y la inteligencia artificial, pone en evidencia una serie de conceptos históricos de género que se encuentran integrados en el lenguaje. Este estudio usó técnicas de aprendizaje automático en el análisis de textos históricos, en particular, el procesamiento del lenguaje natural para determinar los cambios semánticos, el etiquetado de categorías gramaticales y el reconocimiento de entidades nombradas, con el fin de identificar el vocabulario clave sobre género. Adicionalmente, empleó un modelo de n-grama orientado a establecer la terminología que aparece de manera más frecuente junto con las palabras meta. La metodología se aplicó a un corpus histórico de prensa latinoamericana en español, compilado por los autores de la investigación, lo que permitió evidenciar la eficacia de estas tecnologías en el procesamiento de colecciones extensas de fuentes escritas. En efecto, el artículo revela la manera en la que las herramientas de inteligencia artificial permiten dilucidar las ideas de género que subyacen en las fuentes históricas escritas y presenta hallazgos empíricos relacionados con las desigualdades históricas en la representación lingüística. Asimismo, a través de la comparación entre el resultado del corpus de prensa y una obra literaria específica —la novela colombiana Manuela, escrita en 1858 por Eugenio Díaz Castro—, se destacan las tensiones feministas latentes y las ideas revolucionarias en disputa con las normas sociales establecidas. Más allá de aportar un análisis histórico o literario concluyente, se busca invitar a los científicos sociales a involucrarse en la siguiente fase del estudio y a acreditar, mediante la colaboración interdisciplinaria, el potencial de la inteligencia artificial en el fortalecimiento de la interpretación y el análisis crítico de las narrativas históricas. Este trabajo también contribuye a los debates sobre feminismo histórico, pues ofrece un enfoque innovador que integra métodos cualitativos y computacionales, datos abiertos y código, para ampliar las posibilidades de la historiografía tradicional. Como conclusión, el artículo reflexiona sobre cómo mejorar los estudios en semántica de género y enfatiza en el potencial de la integración de disciplinas para promover nuevas rutas de investigación en torno a interrogantes culturales críticos.

Palabras clave | aprendizaje automático; feminismos históricos; inteligencia artificial; procesamiento del lenguaje natural; semántica de género; América Latina del siglo XIX

Semântica de gênero e feminismos históricos: uma abordagem interdisciplinar a partir do processamento de linguagem natural

Resumo | Neste artigo, analisa-se a evolução da semântica de gênero durante o século 19 na América Latina, com ênfase especial nas nuances do significado da palavra mulher. O objetivo principal é apresentar os resultados de uma metodologia interdisciplinar que, a partir de uma análise dual das ciências sociais e da inteligência artificial, destaca uma série de conceitos históricos de gênero que se integram à linguagem. Para isso, aplicaram-se técnicas de aprendizado de máquina na análise de textos históricos, em particular, processamento de linguagem natural para detectar mudanças semânticas, rotulagem de categorias gramaticais e reconhecimento de entidades nomeadas, com o objetivo de identificar vocabulários-chave relacionados ao gênero. Além disso, um modelo de n-gramas para determinar a terminologia que ocorre com maior frequência junto às palavras-alvo. A metodologia foi aplicada a um corpus histórico da imprensa latino-americana em espanhol, compilado pelos autores da pesquisa, o que permitiu comprovar a eficácia dessas tecnologias no processamento de grandes coleções de fontes escritas. De fato, o artigo revela como as ferramentas de inteligência artificial possibilitam elucidar as ideias de gênero subjacentes nas fontes históricas escritas, apresentando achados empíricos acerca das desigualdades históricas na representação linguística. Da mesma forma, por meio da comparação entre o resultado do corpus da imprensa e uma obra literária específica — o romance colombiano Manuela, escrito em 1858 por Eugenio Díaz Castro —, evidenciam-se tensões feministas latentes e ideias revolucionárias em conflito com as normas sociais estabelecidas. Para além de oferecer uma análise histórica ou literária conclusiva, busca-se convidar cientistas sociais a participarem da próxima fase do estudo e reconhecerem, por meio da colaboração interdisciplinar, o potencial da inteligência artificial para fortalecer a interpretação e a análise crítica das narrativas históricas. Além disso, este trabalho também contribui para os debates sobre o feminismo histórico ao oferecer uma abordagem inovadora que integra métodos qualitativos e computacionais, dados abertos e códigos, ampliando as possibilidades da historiografia tradicional. Por fim, no artigo, reflete-se sobre como aprimorar os estudos em semântica de gênero e enfatiza o potencial da integração interdisciplinar para abrir novas vias de pesquisa em torno de questões culturais críticas.

Palavras-chave | aprendizado de máquina; feminismos históricos; inteligência artificial; processamento de linguagem natural; semântica de gênero; América Latina do século 19

Introduction

In exploring feminist discourses, a central theme that persists is the evolving definition of women as a collective identity. 20th-century feminism often emphasizes the collective nature of women, viewing them as a cohesive social group and as individual political entities. However, this perspective requires us to acknowledge the nuances that have historically shaped this idea over time. In 19th-century Latin America, feminist movements grappled with defining what it meant to be a woman within the intricate intersections of public and private spheres. This discourse was deeply influenced by the prevailing socio-political environments of the era, which dictated distinct roles for women as social, political, and cultural actors. As societies delineated these roles based on education, economic status, and cultural norms, understanding how a woman was defined and perceived became a critical point of analysis. This paper investigates these frameworks by applying modern artificial intelligence (AI) techniques, revealing how past narratives continue to inform and transform current feminist philosophies. By examining gender semantics and biases in historical texts, this study expands on the breadth of feminist historiography, providing a more comprehensive understanding of the shifting dimensions of gender semantics.

The primary aim of this paper is to present the results of using an interdisciplinary methodology that integrates social scientists into Machine Learning (ML) technical experiments to explore historical gender constructs. The study leverages Natural Language Processing (NLP) techniques to analyze 19th-century texts and uncover nuanced insights into gender dynamics and feminist discourses. Importantly, this research does not provide an in-depth history of 19th-century feminism or women in Latin America, nor does it offer a literary analysis of the novel Manuela: novela de costumbres colombianas and its reception. Instead, it demonstrates the potential of AI in historical analysis, offering significant first iteration findings that encourage further exploration and collaboration across disciplines and experts. This innovative approach provides a different perspective on how technology can contribute to historical and modern feminist studies, highlighting the intersection of the humanities, technological advancement, and collaborative work.

In the following sections, this paper explores the interplay between historical feminist discourses in printed sources and modern AI techniques. We begin by examining the context surrounding feminist ideas in 19th-century Latin America, laying the groundwork for understanding the socio-political climate of the time. This is followed by a detailed presentation of our methodology, which outlines the research design and analytical pipeline employing ML and NLP techniques to track the evolution of gender biases in gender-related terms. The Results and Discussion section offers an in-depth analysis of selected key terms to elucidate historical gender semantics. In the Conclusion, we synthesize the insights, address the current models’ limitations, and propose directions for future research.

Historical Feminisms in Latin America

In 19th-century Latin America, feminist voices emerged as critical expressions calling for the alignment of women’s rights with liberal and Enlightenment ideals. Concepts such as free markets, the abolition of slavery, and freedom of the press were core to building democratic nations in the region. Yet despite these ideals, societies remained highly segregated. The benefits of the State were reserved for local elites, while other segments of the population gradually began to gain visibility. In this slow-motion process, the discourse surrounding gender roles and societal norms was a field of complex tensions. Writers like Peruvian Clorinda Matto de Turner (1853-1909), Cuban Gertrudis Gómez de Avellaneda (1814-1873), and Colombian Soledad Acosta de Samper (1833-1913) played pivotal roles in discussing the role of 19th-century women.

Both Acosta de Samper and Matto de Turner utilized allegories, comparing women to caged birds in their works, to advocate for the feminization of intellectual spaces (Clark 2014). They promoted the idea that women, through their involvement in literature and education, could be ‘freed’ and contribute significantly to the nation’s prosperity and cultural advancement. Avellaneda’s work served as a medium for critiquing the old structures that marginalized women’s achievements and intellectual contributions, associating the need for women’s political freedom with the emancipation of slaves to build a new nationalism instead of colonialism (Williams 2008). Notably, the three women mentioned above were part of their country’s educated elite, and some, like Acosta de Samper, advocated for an intellectual rather than a political role for women. In her newspaper titled La Mujer. Revista quincenal (1878-1881), she clearly stated the publication’s purpose:

We shall not tell women that they are fair and fragrant flowers, born and created solely to adorn the garden of existence; rather, we shall prove to them that God has placed them in the world to assist their fellow travelers on the rugged path of life, and help them bear the grand and heavy cross of suffering. In short, we shall not speak of the rights of women in society, nor of their pretended emancipation, but of the duties incumbent upon every human being in this transient world.1 (Acosta de Samper 1878)

Thus, Acosta de Samper’s feminist ideas did not involve advocating for the autonomy of subaltern groups but rather fighting against the infantilization of women (Alzate 2015, 160). Her ideas reflect a conservative segment of Nueva Granada’s society regarding the women’s quest, aligning with Catholic discourse. Nonetheless, her stance was revolutionary. She promoted the idea of women in literature, arts, and sciences as legitimate, contesting the predominant role of men in those intellectual endeavors at the time.

The efforts of literate women in 19th-century Latin America were part of a broader movement leveraging literary expression to empower women and carve spaces within predominantly male intellectual domains. Widely known feminist thinkers of the epoch, like Mary Wollstonecraft (1759-1797), Harriet Taylor (1807-1851), and John Stuart Mill (1806-1873), “focused on considering women as political beings capable of reasoning and acting morally, thus, challenging the cultural perception of women attributed to women as weak and emotional subjects”2 (Montoya Upegui 2023, 3). They argued that women had the same intellectual capabilities as men and that recognizing their civil rights, including education, voting rights, and labor protection, benefited social and economic progress. However, these ideas were not widely accepted and enforced during the 19th-century. For example, most Western countries did not grant women voting rights until the late 20th-century.

Discussing the different roles women played in historical societies can help better understand the semantics of gender in Latin America. For instance, the role of illiterate and poor women was not widely discussed, as the focus was on the importance of women’s education. Thus, feminist ideas about non-educated women during 19th-century Latin America remain highly unexplored.

Building on these historical debates, AI tools offer a novel approach to reevaluating and amplifying these feminist narratives. By applying ML techniques to historical newspapers, this article explores gender semantics in the language used to describe women, revealing underlying ideas and evolving public perceptions. Advancements in NLP can highlight how terms historically associated with women have transformed over time, providing insights into major societal trends and shifts regarding gender roles. Using ML to analyze large datasets can also offer a more comprehensive and nuanced understanding of historical gender biases. These methodologies both expand the scope of feminist historiography and challenge contemporary narratives by providing empirical evidence to support the reevaluation of historical texts.

Methodology: NLP for Historical Texts

Our methodology builds on prior work, introducing a novel dataset of 19th-century Latin American newspapers (Manrique-Gómez et al. 2024). LatamXIX3, a carefully curated corpus, allows a wide range of analyses related to historical observations and the evolution of Latin American Spanish, particularly in contrast to modern Spanish. It also ensures a substantial representation of historically underrepresented cultures during the 19th-century.

The dataset consists of 23,522 pages of scanned newspapers from nine different countries in the region: Mexico, Argentina, Colombia, Peru, Chile, Panama, Venezuela, Uruguay, and Ecuador. However, some of these countries remain underrepresented due to the limited digitization of their newspaper collections. During the collection process, the focus was on publications that featured cartoons or illustrations to enable subsequent multimodal modeling. The resulting dataset, which includes newspaper images and text from 1821 to 1905, offers a valuable resource for further research.

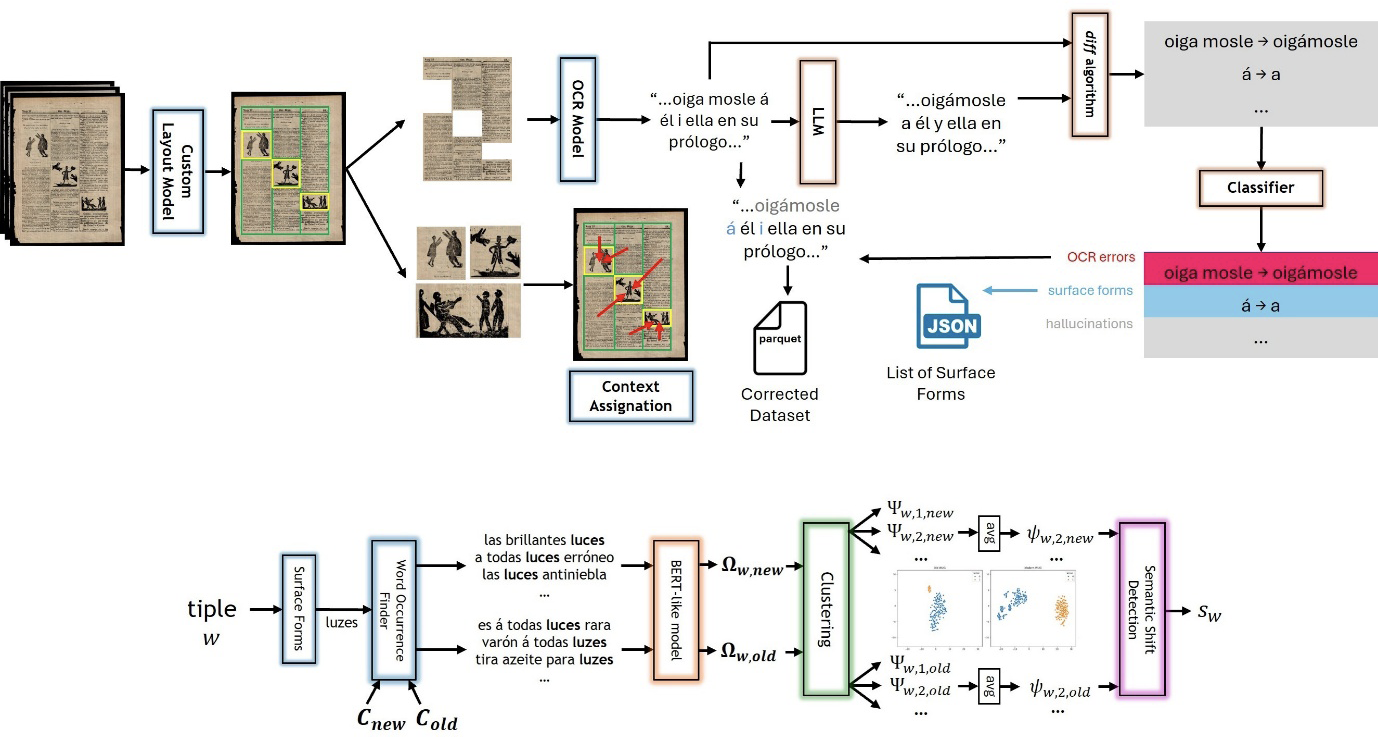

The newspaper dataset was processed using Optical Character Recognition (OCR) technology. However, given the physical degradation of the manuscripts and orthographic variations of the time, the raw OCR outputs contained errors and inconsistencies. As shown in Figure 1, post-OCR processing was performed using Large Language Models (LLMs) to mitigate this. This step improved text readability and reduced OCR artifacts while normalizing orthographic variations. For instance, words like jeneral were standardized to their modern equivalent, general. The resulting corpus contains approximately 28 million tokens and is currently in its second version, with further refinements made since its initial release.

Figure 1. Architecture diagrams of the OCR extraction and SSD pipeline for newspaper image digitization

Source: Montes, Manrique-Gómez, and Manrique (2024) and Manrique-Gómez et al. (2024).

We incorporated a segment from the dataset introduced by Cañete (2019) to compare with modern Spanish. This corpus is a benchmark for evaluating diachronic linguistic changes, particularly in gendered semantics. In addition to the newspaper dataset, we use the novel Manuela, initially published by Eugenio Díaz Castro from 1858 to 1859 in El Mosaico, a literary newspaper he and José María Vergara y Vergara founded. This newspaper is not included in the LatamXIX newspaper dataset. For this research, we used the text from Manuela with a digitized open version taken from the Biblioteca Virtual Miguel de Cervantes website, a full version of the novel published in 1889. The novel presents a portrayal of 19th-century Colombian society. This work is particularly significant in its exploration of gender roles, rural and urban life dynamics, and political ideologies within a patriarchal context. The protagonist, Manuela, symbolizes the struggles of women in a male-dominated society, making the text a rich resource for analyzing gendered semantics. The entire text of the two volumes was consolidated into a single dataset. Although it contains fewer tokens than the newspaper corpus, making it not statistically comparable with the newspaper dataset, Manuela’s dense and semantically rich content complements the broader dataset, enabling detailed qualitative comparisons of gendered vocabulary and concepts.

The methodology was structured into three distinct processes:

1. Vocabulary Extraction and Analysis: A comprehensive extraction of unique vocabulary from the 19th-century corpus was performed, emphasizing terms associated with gender semantics and gender-related contexts. This vocabulary formed the foundation for subsequent diachronic and semantic analyses.

2. Co-occurrence Analysis: Using bigram searches and part-of-speech (POS) tagging techniques, we examined the co-occurrence patterns of target gender-related terms. This analysis identified the most frequent adjectives and nouns associated with these terms, allowing for a comparative study of gendered semantics between the newspaper dataset and Manuela.

3. Semantic Shift Detection (SSD): Building on a previous SSD study conducted on the first version of the newspaper dataset, our contributions are as follows: (i) Fine-tuning: We fine-tuned the model using the updated newspaper corpus, ensuring alignment with the refined dataset; and (ii) Gender-focused analysis: We extended the SSD analysis to examine gender-related semantics, targeting a select set of words for a more targeted exploration of semantic evolution.

Each stage was designed to complement and build on the others, enabling a holistic understanding of gender semantics in 19th-century Latin American Spanish. This approach allowed us to draw meaningful connections between historical and modern linguistic patterns, shedding light on the societal and cultural transformations underpinning these changes.

Vocabulary Extraction and Analysis

The initial step of our methodology focused on the comprehensive extraction and analysis of unique vocabulary across both datasets, leveraging techniques from prior research in keyword extraction and domain-specific term identification. Our approach was inspired by works such as PatternRank (Schopf, Klimek, and Matthes 2020), which used POS tagging and pretrained language models to extract key phrases, along with named entity recognition (NER) and topic modeling-based solutions for social media content analysis (Mehmood et al. 2024). These studies provided foundational insights into adapting language models and analytical frameworks for unstructured and domain-specific text.

To begin, we employed POS and NER tagging on both the 19th-century newspaper dataset and the modern Spanish dataset:

- POS tagging: An NLP task that assigns grammatical roles to words, such as nouns, verbs, adjectives, etc.

- NER tagging: Identifies and categorizes entities within text into locations, persons, organizations, or miscellaneous types—these are the four categories supported by the spaCy Spanish model.

Using the small pre-trained Spanish model from the spaCy library, each word in both datasets was tagged with a POS tag, and each noun, identified as NOUN in POS tagging, had a corresponding NER tag. We also counted the frequency of each word’s association with these tags, resulting in a primary POS tag and, for nouns, a primary NER tag based on the most frequent classifications.

We applied a frequency threshold to ensure data quality and eliminate noise from rare misspellings or OCR errors, retaining only words with more than ten occurrences across the entire dataset. This step effectively removed infrequent typos (for example, “bibliotecq” instead of “biblioteca”) and OCR artifacts (such as “¿¡”) that were unlikely to contribute meaningfully to the analysis. We chose ten as the frequency cutoff after experimentally sorting the words by their frequency and observing that words appearing fewer than ten times tended to be either sporadic errors or noise, while those above this threshold were more likely to be meaningful terms.

To quantify the uniqueness of each word within the datasets, we calculated the log-likelihood ratio (LLR), a statistical measure used to determine the association strength of a word with a specific dataset. The LLR metric evaluates whether the observed word frequencies in one dataset deviate significantly from what would be expected under a null hypothesis of uniform distribution across both datasets.

The LLR for a word w is calculated as:

Where:

- f1 and f2 are the frequencies of w in Dataset 1 (19th-century newspapers) and Dataset 2 (modern Spanish), respectively.

- E1 and E2 are the expected frequencies of w in each dataset, assuming a uniform distribution, which can be computed from the total number of words on each dataset N1 and N2, and the total frequency

:

:

This metric highlights words that appear disproportionately more frequently in one dataset compared to the other. A higher LLR value indicates greater distinctiveness. Using this metric, we generated a ranked list of unique 19th-century words for each dataset, which served several purposes:

This metric highlights words that appear disproportionately more frequently in one dataset compared to the other. A higher LLR value indicates greater distinctiveness. Using this metric, we generated a ranked list of unique 19th-century words for each dataset, which served several purposes:

- Identification of 19th-century vocabulary: Words predominantly found in the historical dataset offered insights into linguistic usage unique to 19th-century Latin American Spanish.

- Percentage presence comparison: By calculating the proportional representation of each word in the historical dataset relative to the modern one, we identified terms that have diminished or persisted over time.

- Semantic focus on nouns: Through NER analysis, we pinpointed the category person, which was highly represented in the historical dataset, shedding light on the thematic emphases of 19th-century texts.

We conducted a manual review of the ranked list to isolate gender-related terms. This final curated list of 326 target words formed the basis for subsequent analyses of gendered semantics and diachronic linguistic shifts, classified into four categories: (i) courtesy title; (ii) occupation or social role; (iii) family role; and (iv) identity descriptor. For example, words were classified as courtesy titles when they conveyed forms of address such as señor (sir) or señora (madam). Occupation or social role was assigned to words like escritor (writer) or escritora (female writer), while family roles were tagged to words such as madre (mother) and padre (father). Finally, the identity descriptor category included words that conveyed defining, socially accepted characteristics like gender, such as mujer (woman) or hombre (man)4. By combining statistical rigor with historical insights, this methodology ensured a robust foundation for exploring gender-related semantic evolution in 19th-century Latin American Spanish.

Contextual Expansion through Co-occurrences

To investigate gender-related semantics within the datasets, we analyzed the co-occurrence patterns of target words extracted in the previous step. This approach is grounded in established lexical co-occurrence principles, as Resnik (2024) noted, where word relationships can be inferred from their frequent proximity in a text. While higher-order co-occurrence methods, such as those leveraged by Latent Dirichlet Allocation (Blei, Ng, and Jordan 2003) or modern large language models, can capture more abstract relationships, our analysis is limited to bigram co-occurrence. This constraint limits the analysis to direct two-word sequences, potentially overlooking semantic nuances that may arise from higher-order relationships.

First, for each target word identified in the vocabulary extension step, we used POS tagging to ensure that both the target word and its co-occurring neighbors were linguistically meaningful. Specifically, bigrams were extracted where the neighboring words were classified as follows: (i) adjectives: providing descriptive or qualitative information about the target word; (ii) nouns: highlighting entities or concepts associated with the target word.

This tagging ensured that co-occurrence analysis focused on semantically significant relationships, filtering out syntactically irrelevant patterns such as articles or conjunctions. Using a sliding window approach, we then examined the preceding and following words for each target word, generating bigrams that captured both: (i) the target word is paired with the previous word; and (ii) the target word is paired with the next word. For example, given the sentence: La mujer valiente enfrenta desafíos, and the target word mujer, the extracted bigram would be only: mujer valiente (following adjective or noun), as la is not relevant to our analysis.

Note that by focusing on bigram co-occurrences, this step provided a focused lens on how gender-related terms interacted with descriptive or conceptual contexts within the datasets. Specifically, adjectival associations or common adjectives co-occurring with gendered nouns revealed prevalent societal attributes or perceptions during the 19th-century, and noun co-occurrences or patterns of associated nouns illuminated thematic links, such as relationships with professions, familial roles, or societal constructs.

Although this method has its limitations in capturing higher-order co-occurrence relationships, it nevertheless yielded valuable semantic insights. We also analyzed the most commonly used particles coupled with the selected nouns, and noted, for example, that some negative words, such as poco and no, did not frequently appear as syntactic modifiers of these nouns. Rather than viewing this as a shortcoming, it should be considered an opportunity for future digital humanities researchers to revisit the results with new questions and investigative paths in mind. Ultimately, this bigram-based analysis offered a structured and interpretable approach to exploring contextual semantics related to gender in the historical dataset. A detailed sample of results is presented in Appendix A.

Semantic Shift Analysis

Building on prior work by Montes, Manrique-Gómez, and Manrique (2024), we conducted an SSD analysis to explore how the meanings of selected gender-related terms evolved from the 19th-century and modern Spanish. Semantic shift refers to the change in a word’s meaning between two different time periods. Sometimes, these changes are easy to visualize—for example, the word servidor, which historically referred to a person serving another individual or, more commonly, the State as a servidor público. Over time, it acquired a new meaning in the context of technological infrastructure. Other changes are more challenging to detect and classify. To address this, we use an automated approach based on LMs such as BERT (Devlin et al. 2019), which encodes a word’s meaning in its context as a semantic embedding.

First, we re-fine-tuned BETO—a BERT-based model specifically trained on Spanish corpora (Cañete et al. 2020)—using the updated version of the 19th-century newspaper dataset. Previous work (Montes, Manrique-Gómez, and Manrique 2024) had only used the earlier version of the dataset. BETO was chosen for its contextual, solid understanding of Spanish, enabling nuanced analyses of historical texts. Fine-tuning BETO on the historical dataset was crucial for adapting the model to the unique linguistic features of 19th-century Spanish. This adaptation allowed the model to generate contextual embeddings representative of the historical era, ensuring meaningful comparisons with modern Spanish embeddings.

For a selected set of gender-related words, we generated contextual embeddings using the fine-tuned BETO model over each word occurrence in each dataset. Contextual embeddings capture the meaning of a word based on its surrounding text, enabling us to assess semantic nuances in different contexts. With the set of word embeddings over each dataset, we then used the cosine similarity to cluster the different meanings of the words across the two datasets.

Given A and B, two contextual embeddings of the target word in different occurrences, their cosine similarity is computed as:

Finally,, when the set of word embeddings are clustered respectively, they are compressed into a two-dimensional space through the t-SNE (Van der Maaten and Hinton 2008) dimensionality reduction technique that preserves similarities between the embeddings to be able to visualize it. The right visualization tool for these semantic shifts is the Diachronic Word Usage Graphs (DWUGs) (Schlechtweg et al. 2021), which consist of three diagrams: the one on the left represents the embeddings of the word in the “old” dataset; the one in the middle, the “modern” dataset; and the one on the right represents all the occurrences overall. Each color corresponds to a different meaning among all three diagrams, revealing the various meanings of a word and how they change diachronically between the two periods. These DWUGs are presented in detail in the Results and Discussion section.

Results and Discussion

NLP techniques combined with qualitative historical methods reveal interesting insights into cultural and gender semantics. This interdisciplinary methodology allows us to uncover the semantic shifts of words as pivotal to understanding historical gender roles and societal structures.

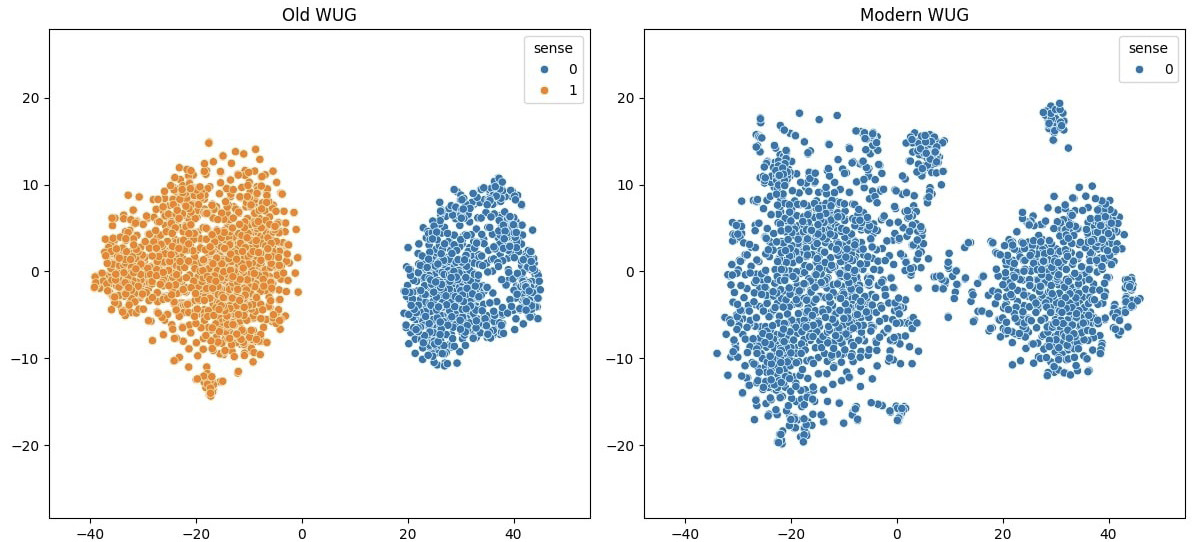

One significant finding using these mixed methods is the semantic transformation of the word mujeres (women) throughout history (Montes, Manrique-Gómez, and Manrique 2024), as shown in Figure 2. In the 19th-century, mujeres was typically used to refer to a specific set of women, a plain plural form indicating a group. It carried connotations tied to domestic roles and separated from the broader term hombres, which was often synonymous with humanity. This linguistic pattern highlights the gendered biases embedded in language, where male terms are defaulted as universal. Consistent with the lexical conventions of 19th-century Spanish, masculine forms of nouns and adjectives were rigorously employed to represent both genders—feminine and masculine (Porto-Dapena 1975).

Figure 2. DWUG of the word mujeres (women)

Note: DWUG visualization of the word mujeres (women), generated using embeddings from the fine-tuned corpus model. The figure employs T-SNE for dimensionality reduction and KMeans clustering (evaluated using the silhouette metric). Each color represents a distinct semantic cluster. The shift in color distributions between the left (old corpus) and right (modern corpus) panels, reflects the overall semantic evolution between the two diachronic corpora.

Source: The authors based on collected data.

Using semantic mapping techniques, we traced how the term mujeres evolved across centuries. The old meanings have largely been supplanted by the modern understanding of women, which refers explicitly to the population segment. These results align with the second wave of human rights in the 20th-century, which expanded the 19th-century’s initial civil rights to include specific rights for various Western population groups, such as women and children. In the 20th-century, influenced by gender studies and feminist discourse, mujeres adopted a more inclusive connotation, signifying a collective female identity distinct from a male-dominated paradigm. Joan W. Scott famously stated, “women’s experience or culture exists only as the expression of female particularity in contrast to male universality” (1999, 197). This idea explains the rupture in the modern usage of the word women toward a relational concept of gender in the 20th-century (Lux and Pérez Pérez 2020). The transformation reflects pivotal societal changes, marking a movement from male-centric definitions to vibrant, autonomous representations of women, thereby enriching feminist scholarly discourse. This paper demonstrates that by applying NLP models to historical texts, researchers can draw significant insights into how societal norms and gender perceptions have been linguistically enshrined and transformed.

Furthermore, using contextual expansion through co-occurrences led to a deeper understanding of the historical ideas behind the term women. The bigram analysis resulted in three groups of gendered terms: (i) Words describing the most relevant features associated with women or men; (ii) irrelevant or non-existent words in the dataset, indicating neglect or absence of specific gender roles, and (iii) feminist ideas embedded in Manuela’s literary work present a narrative divergent from the newspaper collection. A detailed sample of results is presented in Appendix A.

Similar to the pronoun–verb search methods used by Jockers and Kirilloff (2016) to examine gendered agency in 19th-century literature, our analysis expands gendered terms through co-occurrence patterns. The first group of gendered terms with co-occurrences, sheds light on the prevalent stereotypes of women in 19th-century Latin America as depicted in newspapers. Common and significantly relevant terms focused on physical and aging features associated with women. At the same time, descriptions of men commonly included moral values and social roles, as shown in the examples in Appendix A. For instance, the term india (Indigenous woman) was often associated with joven (young) and doncella (unmarried), whereas indio (Indigenous man) was pobre (poor) or salvaje (savage). The criolla (creole woman) was portrayed as hermosa (beautiful), while her male counterpart’s nationality was highlighted, such as being peruano (Peruvian). These examples powerfully reveal the emphasis on sexual attractiveness as a primary descriptor for both indias and criollas. These women, often illiterate and poor, occupied a dual marginalized position—what gender studies now describe as intersectional —in 19th-century Latin America: they were both women and of non-white race.

This analysis also highlights the persistent reduction of women to their physical appearance and marital status, while men are more frequently associated with socioeconomic roles, character, or group belonging. Such linguistic patterns reinforce social hierarchies and support historical systems of patriarchy and racialization—processes whereby gender and ethnic identity interact to shape unequal experiences and expectations. The consistent mention of joven and hermosa also reflects broader societal values that prized youth and beauty in women, as opposed to productive or intellectual qualities.

The recurrent portrayal of Indigenous women as both illiterate and poor underscores how the intersection of gender and ethnicity exacerbated marginalization. This “double bind” rendered Indigenous and mestiza women particularly vulnerable—not only due to their gender, but also because of their ethnicity and social class—a dynamic extensively explored in intersectional feminist theory. Notably, by applying automated co-occurrence and semantic analysis, this study moves beyond anecdotal accounts, offering empirically grounded evidence of historical patterns of gendered and racialized language. Ultimately, such findings invite contemporary researchers to reflect on the lasting impact of these stereotypes and consider the value of computational approaches for uncovering patterns of discrimination that remain subtle yet powerful within large textual corpora.

Other examples are similarly telling. The esposa (wife) was described as joven (young) and infiel (unfaithful) as key characteristics, while the esposo (husband) was mostly depicted as the good-husband or exciting future-husband. The hembra (female) was most likely described as desgraciada (disgraceful), voluble (unstable), or rubia (blonde), while the varón (male) was santo (saint), ilustre (prominent) or justo (righteous). Impious women, impía, were typically described as old, while impious men, impío, were associated with specific social roles such as cazador (hunter) or carcelero (prison guard). The Catholic term beato for men was paired with solitude, while for females, it denoted those who were viejas (old), chismosas (gossipers), and solteronas (spinsters).

These characterizations offer a window into the prevailing social and moral narratives of the time, where language reflected and reinforced rigid gender archetypes. Women were routinely linked with physical attributes, negative emotional qualities, and moral suspicion, thus circumscribing their social identity to youth, faithfulness, and appearance. The recurrent association of wife with youth and infidelity, for instance, reveals cultural anxieties about the sexual agency and fidelity of women, in contrast with idealized and aspirational male roles as husbands.

Furthermore, the terms used to describe women, such as desgraciada or voluble, pathologize feminine behavior and support stereotypes of women as unstable or morally questionable. In contrast, descriptors for men like santo and ilustre confer honor, virtue, and societal respectability, highlighting how language systematically elevated male identity while problematizing or trivializing the female experience. The depiction of impious women as old and impious men through occupational or public roles also demonstrates how deviance was gendered: women’s social value was closely linked to physical and marital status, while men’s deviance was contextualized by their place in public life.

Even religious terminology was laden with gendered distinctions: a beato (pious man) lives in solitude, whereas a beata (righteous woman) is linked to negative stereotypes of being old, gossipy, or an undesirable single woman—a clear example of how identical religious labels accrued very different social meanings depending on gender. This linguistic asymmetry speaks to the underlying power structures at play and aligns with broader feminist and sociolinguistic findings regarding the policing and restriction of women’s identities through discursive means.

Overall, these patterns not only illuminate the mechanisms by which language perpetuated social hierarchies but also underscore the importance of computationally enabled, large-scale textual analysis for identifying subtleties that may escape more traditional, close-reading methodologies. In mapping these gendered semantic landscapes, the analysis thus contributes to historical understanding and ongoing debates about the enduring power of language in shaping gender norms.

Regarding the second group of gendered terms, the irrelevant or non-existent words in the dataset reflect the neglect or absence of specific gender roles, providing meaningful examples. As expected, many social roles or occupations do not appear in the newspaper dataset. Political roles were predominantly masculine, evinced by the absence of terms like jefa (chief), concejala (councilwoman), alcaldesa (mayor), inspectora (inspector), embajadora (ambassador), ingeniera (engineer), or jubilada (retired). This aligns with the lack of civil or political rights granted to women at the time. Conversely, common occupations for lower-ranked women included cocinera (female cook), lavandera (washerwoman), and criada (woman servant). While literate and elite women could pursue more prestigious roles—such as poets, actresses, writers, or instructors for other señoritas—professions likemédicas (medicine practitioners) appeared exclusively among European visitors.

Nevertheless, roles historically significant for women were conspicuously absent from newspaper records, as revealed by NLP models. Terms such as artesana (artisan), monja (nun), and misionera (missionary) rarely appeared. Women artisans, for instance, were prolific in creating portrait miniatures and elaborately embroidered works. Yet, as Skinner (2016) notes, such artistic expressions were likely dismissed as mere domestic crafts, unworthy of being recognized under the artisan label. These omissions in the dataset warrant further investigation, as the newspaper dataset represents only a fraction of the universe of newspapers printed in 19th-century Latin America. Nuns and female missionaries, for instance, held prominent roles during this period. The 19th-century marked a turning point, as female missionaries were first granted permission to travel across the Atlantic. Such journeys were often viewed as bold undertakings, especially for women traveling alone, as noted by Miseres (2017). These women travelers were shaped public opinion in markedly different ways—wealthy women often received admiration, while religious women were largely overlooked:

They were daring and determined women ready to embark on adventures unknown to most women of that era; diligent and enterprising due to the demands of their constant service work; drawn to and enchanted by learning other languages; curious and eager to know and understand other societies with a certain depth, sometimes admiring them even more than their compatriots or contemporary travelers, and motivated and committed to being part of these new realities through work and service.5 (Castro-Carvajal 2014, 121)

When comparing these results with the bigram analysis of the Colombian novel Manuela from the same period, the author evidently embedded a fictional feminist narrative where illiterate women play significant roles in society, and gender stereotypes are challenged. Eugenio Díaz Castro is widely recognized as a representative writer of Colombian costumbrist literature, often perceived as inferior to the romantic literature of the time due to its perceived outdatedness and moralizing tone. Thus, Manuela (1859) was eclipsed in public opinion by Jorge Isaacs’ novel María (1864). However, as Rodríguez-Arenas (2011) notes, this marginalization was likely fueled by Díaz Castro’s political adversaries rather than a fair literary critique. While Eugenio Díaz Castro has not been explicitly considered a feminist thinker, NLP models have revealed a distinct feminist discourse in Manuela that deviates substantially from contemporary newspapers and differs markedly from María. This latter novel, with its conventional portrayal of femininity, remains part of Colombian school curricula to this day, whereas Manuela has largely faded from public memory at the local scale.

Results from contextual expansion through co-occurrences revealed Díaz Castro’s subtle messaging in his choice of words. For example, the word viajera (female traveler), often used in newspapers to refer to distinguished European visitors and artists, does not appear in Manuela. Instead, it is used solely to refer to mulas-viajeras (mules for travel), a common form of transportation in the Colombian countryside. The roles of European women visitors were highly exalted in local newspapers, suggesting a deliberate choice by the author of Manuela, whose narrative intent was, conversely, to exalt rural women. Díaz Castro also chose to depict peasant and illiterate women of various types and morals, presenting a female (perhaps imagined) world outside the city of Bogotá. This world includes peonas and trapicheras (female workers), arrendatarias (female leaseholders), and pro-mujeres as opposed to pro-hombres (female political leaders). None of these roles are represented in the newspaper dataset.

As depicted in Figure 1, ML models were trained to process original archival images, transcribe them using OCR, layout analysis models from computer vision, and leverage LLMs to enhance the transcription of historical newspapers, specifically to the historical nuances of Latin American Spanish. This pipeline then feeds into the SSD framework to extract semantic shifts of specific terms. These models revealed the word tiple as another example of gendered discourse embedded in historical texts. There were two primary meanings of the word tiple in Latin America during the 19th-century. The first is the Colombian traditional musical instrument, which appears only in Colombian newspapers; the second relates to Mexican vedettes. It has long been claimes that the tiple originated as a musical instrument in Colombia—a claim now supported through computational analysis. The Latam XIX newspaper dataset confirms that in Colombia, the term tiple was used exclusively to denote a musical instrument, whereas in Mexico, it carried an entirely different meaning.

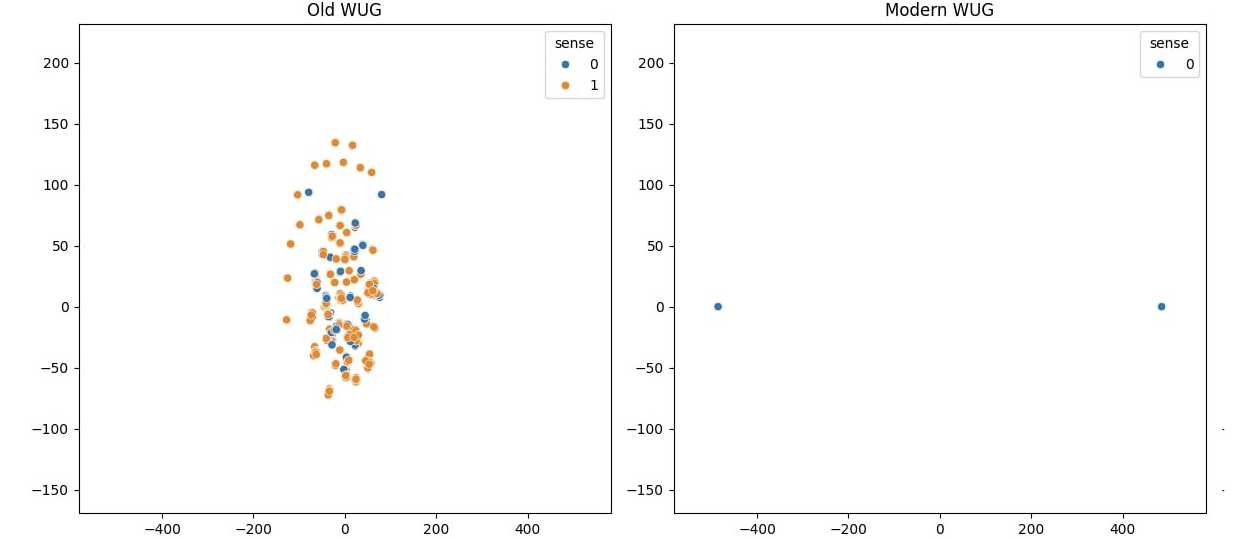

Our SSD analysis showed the divergent meanings of the term tiple across Latin America, as depicted in Figure 3. In Colombia, the tiple is revered as a traditional musical instrument emblematic of folk culture and national identity. It has served as a cultural cornerstone, existing partly in resistance to the elite preferences for European classical music. The Colombian tiple has evolved from a humble, overlooked instrument into a celebrated symbol of vibrancy and authenticity in Colombian music. In contrast, in Mexico, the term tiple referred to female comic performers known for their high-pitched voices. AI models revealed the idea behind these tiple cómicas, often dismissed in cultural hierarchies, paralleling the initial undervaluation of the Colombian instrument. The SSD model helped uncover the social and gender biases that relegated tiple cómicas to the margins, while also highlighting their cultural significance in expressing societal attitudes towards femininity and performance.

Figure 3. DWUG of the word tiple

Note: Each color represents a meaning (cluster) of the word. The color changes between the left (old corpus) and right (modern corpus) panels illustrate the overall semantic change between the two diachronic corpora.

Source: The authors based on collected data.

The Colombian novel Manuela further contextualizes the relationship between popular customs, music, women, and the tiple. As a work of fiction, the novel is deeply symbolic, with the character Manuela—a peasant woman representing rural, authentic Colombia—juxtaposed against Demóstenes, who embodies urban enlightenment and progress. By placing women in roles uncommon for their time, such as landowners and political figures, Manuela explores themes of divergent feminism through its characters and thematic contrasts between city and rural life, challenging existing societal norms. It highlights the breadth of female agency, positioning women at the heart of cultural transformation and contesting male hegemony.

The tension between the “backwardness and progress” or “barbarism and civilization” was a common debate in Latin American that emerged in literature but also in personal correspondence as Argentine President Domingo Faustino Sarmiento, for example, depicts the duality in terms of Muslim women, Spanish Catholic Church as opposed to Parisian science and women in the United States (Davies, Brewster, and Owen 2006). In Manuela, the path from barbarism to civilization is surprisingly inverted. Demóstenes’ urban refinement and civilization end up being “conquered” by barbarism. At the beginning of his journey, Demóstenes regarded the peasant life with disgust, including its music, dancing habits, instruments such as tiples, and the behavior of peasant women. But at the end of his journey, he appreciated all of these things. One of his first references to tiples was a scene where two peasant women were supposed to chant accompanied by tiples, and he made fun of them:

The musicians fell silent in order to compose, as they said, because Rosa and Paula were going to sing. “We shall hear the song of death,” said Don Demóstenes. An angel’s entrance into heaven and a mother’s pain are the objects of sublime poetry. They will not sing such a lofty thing as the poem of the death of the Count of Noroña; but I believe that they will not come out lackluster. Rosa and Paula coughed, and accompanying their voices with the music of the tiples they sang [...] “This is iniquitous,” said Don Demóstenes.6 (Díaz Castro [1859] 2011, 252).

Interestingly, to deepen the understanding of the association between the tiple and unrefined women, AI models applied to the Latam XIX newspaper dataset, uncovered a striking example: a text in which women, the tiple, and popular culture are invoked to depict a distasteful scene in China. The account is narrated through the eyes of Don Nicolás Tanco Armero—a prominent political figure and Colombian international traveler of the period—who reinforces the notion of the tiple as synonymous with the popular, the uncivilized, and the socially disreputable women.

On these grand occasions is when they eat chickens and eggs and hire the gaichas, women of easy virtue, who are paid to play, sing, and dance during the feast. The instrument they play is the samecen, a type of mandolin or tiple with only three strings, very out of tune and unpleasant. The singing is horrible; their howls and cacophonous screams are the most unpleasant you can imagine. While the gaichas exhaust themselves this way, the other companions indulge in lascivious dances, somewhat similar to the French cancan and akin to the exuberance of African or Habanera dances.7 (Colombia Ilustrada, January 31, 1891)

These insights illustrate how a combined approach of semantic analysis and qualitative methodologies can bring hidden narratives to the surface. This dual examination not only illuminates the historical significance and complexities of gender constructs but also challenges contemporary narratives, offering new lenses through which feminist historiography can be reinterpreted and expanded.

Conclusion

This study explored the complex intersections of gender semantics in 19th-century Latin America through the dual lenses of historical analysis and AI methodologies. By examining both literary works, such as the Colombian novel Manuela, and the historical newspaper dataset LatamXIX, this research revealed the dynamic and evolving ideas on women. It underscored the often-hidden narratives embedded in language, highlighting discrepancies between common societal perceptions and literary representations of women’s roles. This perspective might help understand Barbara Taylor’s assertion: “Gender is a mythology. It is mythic because the elements that compose it are not, for the most part, openly articulated propositions but unspoken assumptions, expectations, fantasies” (2024, 2). She may be referring to recognizing the complex possibilities in conceptualizing women concerning linguistics, historical period, cultural specificities, and the limitations of historical sources. Applying NLP techniques, such as contextual embedding and bigram analysis, provided empirical insights into historical gender bias, revealing how semantic shifts reflect broader social and cultural transformations. Our study demonstrated that AI models allow emergent cultural discourses that are otherwise lost in traditional historiographical approaches, paving the way for a deeper understanding of the historical contingencies shaping concepts of gender and identity.

Looking to the future, this research suggests promising directions for incorporating AI techniques into studying historical semantics, particularly in enriching digital humanities and feminist historiography. While the methodologies employed provided significant insights, the study also faced limitations inherent in ML models. These models need more nuanced contextual interpretations and may oversimplify complex historical phenomena. Highlighting the importance of the interpretations of social scientists. Additionally, the representativeness of the datasets—limited to available texts—may not fully encapsulate the rich diversity of experiences and expressions across broader historical narratives. Addressing these limitations calls for the expansion of datasets to include underrepresented voices and the integration of more advanced, context-aware LLMs. By continuing to refine AI approaches in the analysis of historical texts, future research can further elucidate the multifaceted and evolving landscape of gender discourse over time, contributing to a more comprehensive and inclusive historiographical record.

References

Primary Sources

- Acosta de Samper, Soledad. 1878. Prologue to La Mujer. Revista Quincenal n.° 1, September 1. Bogotá: Biblioteca Nacional de Colombia (BNC). Hemeroteca Digital. https://bnco.ent.sirsi.net/custom/web/content/conservacion/html/visorFicheros.html?idFichero=88932

- Colombia Ilustrada. 1891. Year 1, January 31. Bogotá: Biblioteca Nacional de Colombia (BNC). Hemeroteca.

- Díaz Castro, Eugenio. 1889. Manuela: novela de costumbres colombianas. Biblioteca Virtual Miguel de Cervantes. https://www.cervantesvirtual.com/obra-visor/manuela-novela-de-costumbres-colombianas-tomo-primero--0/html/ff1e97e4-82b1-11df-acc7-002185ce6064_2.html

- Díaz Castro, Eugenio. (1859) 2011. Manuela: novela bogotana. Edited by Flor María Rodríguez-Arenas. Miami: Stockero.

Secondary Sources

- Alzate, Carolina. 2015. Soledad Acosta de Samper y el discurso letrado de género: 1853-1881. Madrid; Frankfurt: Iberoamericana Vervuert.

- Blei, David M., Andrew Y. Ng, and Michael I. Jordan. 2003. “Latent Dirichlet Allocation.” Journal of Machine Learning Research 3: 993-1022. https://dl.acm.org/doi/10.5555/944919.944937

- Castro Carvajal, Beatriz. 2014. “La escritura de las monjas francesas viajeras en el siglo XIX.” Anuario Colombiano de Historia Social y de la Cultura 41 (1): 91-126. https://doi.org/10.15446/achsc.v41n1.44765

- Clark, Emily Joy. 2014. “The Caged Bird and the Female Writer: A Recurring Metaphor in Women’s Hispanic Prose from the Mid-Nineteenth Century.” Letras Femeninas 40 (2): 199-215. https://doi.org/10.2307/44733729

- Cañete, José. 2019. “Compilation of Large Spanish Unannotated Corpora.” Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3247731

- Cañete, José, Gabriel Chaperon, Rodrigo Fuentes, Jou-Hui Ho, Hojin Kang, and Jorge Pérez. 2020. “Spanish Pre-Trained BERT Model and Evaluation Data.” Paper presented in the Practical ML for Developing Countries (PML4DC) Workshop, ICLR 2020, online. https://doi.org/10.48550/arxiv.2308.02976

- Davies, Catherine, Claire Brewster, and Hilary Owen. 2006. South American Independence: Gender, Politics, Text. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press.

- Jacob Devlin, Ming-Wei Chang, Kenton Lee, and Kristina Toutanova. 2019. “BERT: Pre-training of Deep Bidirectional Transformers for Language Understanding”. In Proceedings of the 2019 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, Volume 1 (Long and Short Papers), pages 4171–4186, Minneapolis, Minnesota. Association for Computational Linguistics.

- Jockers, Matthew, and Gabi Kirilloff. 2016. “Understanding Gender and Character Agency in the 19th Century Novel.” Journal of Cultural Analytics 2 (2): 1-26. https://doi.org/10.22148/16.010

- Lux, Martha, and María Cristina Pérez Pérez. 2020. “Los estudios de historia y género en América Latina”. Historia Crítica 77: 3-33. https://doi.org/10.7440/histcrit77.2020.01

- Manrique-Gómez, Laura, Tony Montes, Arturo Rodríguez-Herrera, and Rubén Manrique. 2024. “Historical Ink: 19th Century Latin American Spanish Newspaper Corpus with LLM OCR Correction.” In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Natural Language for Digital Humanities, 132-139. November, Miami, United States. https://doi.org/10.18653/v1/2024.nlp4dh-1.13

- Mehmood, Ayaz, Muhammad Tayyab Zamir, Muhammad Asif Ayub, Nasir Ahmad, and Kashif Ahmad. 2024. “A Named Entity Recognition and Topic Modeling-based Solution for Locating and Better Assessment of Natural Disasters in Social Media.” arXiv:2405.00903. https://doi.org/10.48550/arxiv.2405.00903

- Miseres, Vanesa. 2017. Mujeres en tránsito: viaje, identidad y escritura en Sudamérica (1830-1910). Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press.

- Montes, Tony, Laura Manrique-Gómez, and Rubén Manrique. 2024. “Historical Ink: Semantic Shift Detection for 19th Century Spanish.” In Proceedings of the 5th Workshop on Computational Approaches to Historical Language Change, 29-41. August, Bangkok, Thailand. https://doi.org/10.18653/v1/2024.lchange-1.4

- Montoya Upegui, Laura. 2023. “Balance sobre teorías feministas: un cuestionamiento a la noción de ‘mujer’ como sujeto de análisis”. Comprehensive doctoral essay, Universidad de los Andes, Colombia.

- Porto-Dapena, José-Álvaro. 1975. “En torno a las entradas del ‘diccionario’ de Rufino José Cuervo.” Boletín del Instituto Caro y Cuervo 30 (1): 113-152. https://thesaurus.caroycuervo.gov.co/index.php/rth/article/view/1597

- Resnik, Philip. 2024. “Large Language Models are Biased Because They Are Large Language Models.” arXiv: 2406.13138. https://doi.org/10.48550/arxiv.2406.13138

- Rodríguez-Arenas, Flor María. 2011. “Manuela. Novela Bogotana (1859) de Eugenio Díaz Castro: La ideología y el realismo de medio siglo.” Preface to Manuela: novela bogotana. Edited by Flor María Rodríguez-Arenas. Miami: Stockero.

- Schlechtweg, Dominik, Nina Tahmasebi, Simon Hengchen, Haim Dubossarsky, and Barbara McGillivray. 2021. “DWUG: A large Resource of Diachronic Word Usage Graphs in Four Languages.” In Proceedings of the 2021 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, 7079-7091. November, online and Punta Cana, Dominican Republic. https://aclanthology.org/2021.emnlp-main.567

- Schopf, Tim, Simon Klimek, and Florian Matthes. 2022. “PatternRank: Leveraging Pretrained Language Models and Part of Speech for Unsupervised Keyphrase Extraction.” In Proceedings of the 14th International Joint Conference on Knowledge Discovery, Knowledge Engineering and Knowledge Management–KDIR, 243-248. October 24-26, Valletta, Malta. https://doi.org/10.48550/arxiv.2210.05245

- Scott, Joan Wallach. 1999. Gender and the Politics of History. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Skinner, Lee. 2016. Gender and the Rhetoric of Modernity in Spanish America: 1850-1910. Gainesville: University Press of Florida.

- Taylor, Barbara. 2024. “History, Feminism and the Feeling Woman.” History Workshop Journal 98: 125-134. https://doi.org/10.1093/hwj/dbae027

- Van der Maaten, Laurens, and Geoffrey Hinton. 2008. “Visualizing Data using t-SNE.” Journal of Machine Learning Research 9 (86): 2579-2605. http://jmlr.org/papers/v9/vandermaaten08a.html

- Williams, Claudette. 2008. “Cuban Anti-Slavery Narrative through Postcolonial Eyes: Gertrudis Gómez de Avellaneda’s Sab.” Bulletin of Latin American Research 27 (2): 155-175. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1470-9856.2008.00261.x

Results of contextual expansion using co-occurrence analysis. The table includes the calculated LLR Ratio, a statistical measure of the strength of association between a word and a specific dataset.

|

Target Gendered Term |

Description/Role |

Attributes in Newspapers with % LLR Metrics (Relevance) |

|

Mujer (woman) |

Identity/Moral values |

Pobre 29% (poor), buena 13% (good), hermosa 12% (beautiful), infeliz 10% (unhappy)In Manuela: bondadosa 50% (kind), acusada 50% (acused), madre 67% (mother) |

|

Hombre (man) |

Identity/Moral values |

Grande 19% (important), honrado 16% (honest), buen 12% (good), pobre 12% (poor)In Manuela: dichoso 17% (happy), preso 17% (prisioner), humanitario 17% (altruistic) |

|

India (indigenous woman) |

Identity/Moral values |

Joven 15% (young), doncella 15% (unmarried) |

|

Indio (indigenous man) |

Social role/Moral values |

Pobre 24% (poor), salvaje 8% (savage) |

|

Criolla (creole woman) |

Identity/Moral values |

Hermosa 33% (beautiful), negra 17% (black) |

|

Esposa (wife) |

Family role |

Joven 20% (young), infiel 17% (unfaithful), buena 16% (good) |

|

Esposo (husband) |

Social role/Moral values |

Buen 27% (good), futuro 19% (future-husband) |

|

Hembra (female) |

Physical/Moral attributes |

Desgraciada 17% (disgraceful), voluble 8% (unstable), rubia 8% (blonde) |

|

Varón (male) |

Social role/Moral values |

Santo 57% (saint), ilustre 12% (prominent), justo 21% (righteous) |

|

Impía (impious woman) |

Moral values/Social role |

Vieja 50% (old) |

|

Impío (impious man) |

Moral values/Social role |

Cazador 14% (hunter), carcelero 14% (prison guard) |

|

Beata (righteous woman) |

Social/Moral attributes |

Vieja 23% (old), chismosa 15% (gossiper), solterona 18% (spinster) |

|

Jefa (chief), concejala (councilwoman), alcaldesa (mayor), inspectora (inspector), embajadora (ambassador), ingeniera (engineer), jubilada (retired) |

Social role (absent in newspapers) |

Absent |

|

Cocinera (female cook) |

Common occupations for lower-ranked women |

Vieja 35% (old), pobre 12% (poor), mofletuda 10% (fat), lujuriosa 6% (lascivious) |

|

Lavandera (washerwoman) |

Common occupations for lower-ranked women |

Vieja 33% (old), joven 33% (young)In Manuela: Joven 50% (young), honrada 50% (honest) |

|

Criada (servant) |

Common occupations for lower-ranked women |

Respondona 65% (insolent), vieja 30% (old), humilde 9% (humble) |

|

Artesana (artisan), monja (nun), misionera (missionary) |

Historically relevant social roles (absent in newspapers) |

Absent |

|

Médica (medicine practitioner) |

Social role/Moral values |

Parisiense 33% (Parisian) |

|

Escritora (writer) |

Social role/Moral values |

Distinguida 35% (distinguished), notable 16% (prominent) |

|

Actriz (actress) |

Social role/Moral values |

Primera 49% (first), Sra. 40% (madam), simpática 8% (kind) |

|

Profesora (instructor) |

Social role/Moral values |

Inteligente 27% (intelligent), distinguida 13% (distinguished), modistas 7% (dressmaker) |

|

Poetisa (poet) |

Social role/Moral values |

Distinguida 24% (distinguished), señorita 20% (miss), amiga 20% (friend), inspirada 21% (inspired) |

|

Viajera (female traveler) |

Associated with European visitors in newspapers |

Hermosa 33% (beautiful), ilustre 13% (prominent) In Manuela: mula 100% (mule) |

|

Peona (female worker), trapichera (female worker), arrendataria (female leaseholders) |

Roles depicted in Manuela; absent in newspapers |

Absent |

Source: The authors based on collected data.

✽ This article is based on Laura Manrique-Gómez’s ongoing research project, “Historical Ink: Machine Learning for a History of Emotions in Latin America 19th Century,” conducted as part of her Ph.D. research in History at Universidad de los Andes (Colombia). A special thank you to Dr. Jaime Humberto Borja for his invaluable comments and insights. This research has not been funded by any grants. All authors contributed to the study’s conception and design. Laura Manrique-Gómez prepared the manuscript and performed data collection and analysis. Tony Montes was responsible for the experiments’ settings and contributed to the manuscript’s writing. Rubén Manrique provided supervision and mentorship during all the research and provided critical revisions to the manuscript. Grammarly v1.2.139.1613 was used to improve review language.

1 Author’s translation. The original text in Spanish reads: “No les diremos a las mujeres que son bellas y fragantes flores, nacidas y creadas tan solo para adornar el jardín de la existencia; sino que las probaremos que Dios las ha puesto en el mundo para auxiliar a sus compañeros de peregrinación en el escabroso camino de vida, y ayudarles a cargar la grande y pesada cruz del sufrimiento. En fin, no les hablaremos de los derechos de la mujer en la sociedad, ni de su pretendida emancipación, sino de los deberes que incumben a todo ser humano en este mundo transitorio.”

2 Author’s translation. The original text in Spanish reads: “Estos pensadores se centraron en demostrar que las mujeres tenían la capacidad de razonar y actuar moralmente, desafiando la percepción cultural atribuida a las mujeres como sujetos débiles y emocionales.”

3 The dataset is available in its three versions: “original”, “cleaned”, and “corrected” at https://huggingface.co/datasets/Flaglab/latam-xix. Processing steps are available at https://github.com/historicalink/LatamXIX

4 The complete list of target words and their contextual expansion through co-occurrences are available in the project’s repository at https://github.com/historicalink/genderbias

5 Author’s translation. The original text in Spanish reads: “Unas mujeres atrevidas y resueltas a lanzarse a aventuras desconocidas para la mayoría de las mujeres de esa época; diligentes y emprendedoras por la exigencia que su trabajo de servicio permanente demandaba; atraídas y encantadas por aprender otros idiomas; inquietas y asombradas por conocer y comprender otras sociedades con cierta profundidad, a veces, incluso, admirándolas más que sus coterráneos o los viajeros contemporáneos y motivadas y comprometidas por ser parte de estas nuevas realidades a través del trabajo y el servicio.”

6 Author’s translation. The original text in Spanish reads: “Callaron los músicos con el objeto de componer, como dijeron ellos, porque Rosa y Paula iban a cantar. Oiremos la muerte —dijo Don Demóstenes—. La entrada de un ángel al cielo y el dolor de una madre son objetos de una poesía sublime. No cantarán una cosa tan elevada como el poema de la muerte del conde de Noroña; pero yo creo que no saldrán deslucidas. Rosa y Paula tosieron, y acompañando a sus voces la música de los tiples cantaron lo que sigue: [The lyrics are not translated: Lará, lara/ El hombre que se enamora/ De mujer que no lo quiere/ Merece cincuenta azotes/ Cantándole el miserere./ Lará, lará/ La mujer que se enamora/ De un hombre que la enjarana/ Merece noventa azotes/ Cantándole la tirana]. —Esto es inicuo— dijo don Demóstenes.”

7 Author’s translation. The original text in Spanish reads: “En estas grandes ocasiones es cuando comen gallinas y huevos, y contratan a las gaichas, mujerzuelas de la vida alegre, a quienes se les paga porque toquen, canten y bailen durante el festín. El instrumento que se toca es el samecen, especie de bandola o tiple con solo tres cuerdas, muy destemplado y desapacible. El canto es horroroso; sus alaridos y gritos cacofónicos de lo más desagradable que se pueda imaginar. Mientras las gaichas se desgañitan de este modo, las otras compañeras se entregan a bailes lascivos, algo parecidos al cancán francés y a la sopimpa de las danzas africanas o habaneras.”

Ph.D. candidate in History at Universidad de los Andes, Colombia. Her research focuses on digital history, emphasizing the interaction between computational and historical methodologies using Machine Learning to study 19th-century Latin American visual and printed sources. She is a researcher with the Natural Language Processing group at Universidad de los Andes on projects involving historical OCR correction, emotions, irony, and semantic shift detection. Recent publication: “Ciencia de datos para la historia: datificar las fuentes para una historia (predictiva)” (co-authored), in Historia y Grafía 64: 97-145, 2025, https://doi.org/10.48102/hyg.vi64.541. https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0843-8157 | l.manriqueg@uniandes.edu.co

Bachelor degree in Systems Engineering and Electronics Engineering at Universidad de los Andes, Colombia. He is currently a Research Intern in Machine Learning at Cornell University, United States, and a Junior Data Engineer at ProCibernética. With a solid background in software development and NLP research. t.montes@uniandes.edu.co

Ph.D. in Engineering from Universidad de los Andes, Colombia. Assistant Professor in the Computer Science Department at the same institution. His recent research includes analyzing Machine Learning Models for predicting academic performance, enhancing autonomous task execution in social robots using Large Language Models, and developing a translation tool for indigenous dialects as well as historical semantic shift detection. Recent publications: “Integrating Large Language Model-Based Agents into a Virtual Patient Chatbot for Clinical Anamnesis Training” (co-authored), Computational and Structural Biotechnology Journal 27: 2481-2491, 2025, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.csbj.2025.05.025; and “Preserving Heritage: Developing a Translation Tool for Indigenous Dialects” (co-authored), paper presented in WSDM ‘24: Proceedings of the 17th ACM International Conference on Web Search and Data Mining, 1200-1203, 4-8 March, 2024, New York, United States, https://doi.org/10.1145/3616855.3637828. https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8742-2094 | rf.manrique@uniandes.edu.co