Algocracy in the Judiciary: Challenging Trust in the System✽

Received: December 13, 2024 | Accepted: May 6, 2025 | Modified: June 13, 2025

https://doi.org/10.7440/res93.2025.06

Abstract | This article examines how algocracy—the delegation of judicial decision-making to algorithmic systems—affects public trust in courts operating within increasingly AI-mediated, multi-level governance structures. It argues that legal legitimacy relies on normative correctness and the social acceptance that emerges from trust. Using a qualitative methodology that integrates doctrinal analysis, comparative regulatory review, and case studies from Mexico, Australia, Germany, the Netherlands and Denmark, this study develops an interpretive framework comprising five principles—transparency, responsibility, understanding, social justice and trustworthy oversight. It applies this framework to a typology of eight algorithmic decision-making tools to assess their impact on individual, institutional and societal trust. The findings indicate that confidence erodes when systems function opaquely, involve uncontrolled delegation or inherit data biases—conditions that can provoke legitimacy crises and civic resistance. The proposed framework therefore provides practical guidance for designing, auditing, and implementing algorithmic tools that preserve human deliberation and equal access to justice. By bridging philosophical debates on algocracy with legal analysis focused on trust, the study offers an original, interdisciplinary tool to help courts govern technological innovation without compromising democratic legitimacy today.

Keywords | algocracy; artificial intelligence; judicial system; public trust

Algocracia en el Poder Judicial: un desafío a la confianza en el sistema

Resumen | Este artículo analiza la manera en que la algocracia —la delegación de la toma de decisiones judiciales a sistemas algorítmicos— afecta la confianza ciudadana en los tribunales que funcionan dentro de estructuras de gobernanza multinivel cada vez más mediadas por la inteligencia artificial. El artículo sostiene que la legitimidad legal depende de la ética normativa y de la aceptación social que se desprende de la confianza. A partir de una metodología cualitativa que incorpora el análisis doctrinal, la evaluación regulatoria comparada y el estudio de casos en México, Australia, Alemania, Países Bajos y Dinamarca, esta investigación desarrolla un marco interpretativo que se compone de cinco principios: la transparencia, la responsabilidad, la comprensión, la justicia social y la supervisión confiable. El marco es implementado en una tipología de ocho herramientas de toma de decisiones basadas en algoritmos, orientadas a evaluar su impacto en la confianza individual, institucional y social. Los hallazgos indican que la confianza se erosiona cuando los sistemas funcionan de manera opaca, involucran la delegación sin control y reproducen el sesgo de datos, condiciones que pueden desencadenar crisis de legitimidad y resistencia cívica. De esta manera, el marco propuesto proporciona unas directrices prácticas para el diseño, la auditoría y la implementación de herramientas algorítmicas capaces de asegurar la deliberación humana y el acceso igualitario a la justicia. Este trabajo tiende puentes entre los debates filosóficos sobre algocracia y los análisis legales centrados en la confianza, con el fin de aportar una herramienta original e interdisciplinaria para asistir a los tribunales en la gestión de la innovación tecnológica sin comprometer la legitimidad democrática.

Palabras clave | algocracia; confianza ciudadana; inteligencia artificial; sistema judicial

Algocracia no judiciário: um desafio à confiança no sistema

Resumo | Neste artigo, analisa-se como a algocracia — a delegação da tomada de decisões judiciais a sistemas algorítmicos — afeta a confiança do público nos tribunais que funcionam dentro de estruturas de governança multinível cada vez mais mediadas por inteligência artificial. Argumenta-se que a legitimidade jurídica depende da ética normativa e da aceitação social que advém da confiança. A partir de uma metodologia qualitativa, que inclui análise doutrinária, avaliação regulatória comparada e estudos de caso na Alemanha, na Austrália, na Dinamarca, na Holanda e no México, esta pesquisa desenvolve uma estrutura interpretativa composta por cinco princípios: transparência, responsabilidade, compreensão, justiça social e supervisão confiável. Além disso, propõe-se uma tipologia de oito ferramentas algorítmicas de tomada de decisão, com o objetivo de avaliar seu impacto na confiança individual, institucional e social. Os resultados indicam que a confiança é corroída quando os sistemas funcionam de maneira não transparente, envolvem delegação sem controle e reproduzem viés de dados, condições que podem desencadear crises de legitimidade e resistência cívica. Dessa forma, a estrutura proposta fornece diretrizes práticas para a concepção, auditoria e implementação de ferramentas algorítmicas que assegurem a deliberação humana e a igualdade de acesso à justiça. Este trabalho preenche a lacuna existente entre os debates filosóficos sobre algocracia e as análises jurídicas relacionadas à confiança, a fim de oferecer uma ferramenta original e interdisciplinar para auxiliar os tribunais na gestão da inovação tecnológica sem comprometer a legitimidade democrática.

Palavras-chave | algocracia; confiança do cidadão; inteligência artificial; sistema de justiça

Introduction

In 2020, the short film Please Hold captured the growing tension between technology and human interaction, particularly within a penal system increasingly devoid of human involvement (Dávila 2020). The story follows Mateo, a young Latino man who is unjustly arrested by a police drone and confined in an automated jail. With no opportunity to speak to a human being, he is left to navigate a cold, computerised bureaucracy in his pursuit of justice. The film delivers a sharp social critique of a dehumanised, profit-driven penal system—one in which marginalised communities disproportionately bear the consequences. The film not only exposes the frustrations of being unable to engage with a human being, but also reflects a broader societal shift. As technology has evolved, our communication has become more efficient—yet paradoxically, more impersonal. When technology fails, or when the stakes are high, we instinctively revert to our primal urge to seek out human contact. The film raises pressing questions for legal theory and practice: What is lost when human judgment is replaced by algorithmic systems? And when individuals are subjected to automated decision-making, what becomes of their trust in the institutions?

The film underscores how the absence of human interaction in domains such as law enforcement can lead to frustration, dehumanisation, and a breakdown of trust in the system. These concerns are amplified in the context of Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Automated Decision-Making (ADM) systems increasingly integrated into the judiciary processes. While such technologies promise greater efficiency—whether by optimising resource allocation or enhancing law enforcement—they also critical questions about legitimacy, accountability, and human dignity. Concepts such as algorithmic governance, algorithmic bureaucracy, and algorithmic government refer to the expanding role of algorithms in collecting, organising, and processing data for decision-making and communication within governance frameworks (Aneesh 2009; Danaher 2016; Williamson 2015). These systems not only influence governance structures but also shape the organisation of social life and actions.

Within the judiciary, AI-driven algorithms are used to analyse vast amounts of data, identify patterns, and provide recommendations, or even make decisions based on predefined rules and objectives. These systems hold the potential to streamline judicial processes, enhance efficiency, and mitigate certain forms of human bias (Stankovich et al. 2023). However, the integration of algocratic systems into judicial practice introduces a range of ethical, legal, and social challenges. Recent rulings have revealed a growing dependence on AI and generative AI tools by judges, raising concerns about how these tools affect public trust in the judicial system (Gutiérrez 2024a). In multilevel governance systems, such concerns are magnified, as AI’s role in decision-making may impact the transparency and fairness expected of judicial outcomes.

While much of the literature on algorithmic governance—including Danaher’s concept of algocracy (2016)—focuses on the normative legitimacy of such systems, this paper explores a complementary dimension: the role of public trust in mediating perceptions and acceptance of legitimacy within technologically mediated judicial contexts. Drawing on Popelier et al. (2022), trust is understood not as a vague sentiment or psychological state, but as a relational, context-specific phenomenon shaped by perceptions of competence, integrity, and benevolence. In judicial settings where algorithmic tools are opaque or difficult to contest, citizens are often compelled to rely on trust as a practical proxy for assessing institutional reliability. This perspective highlights that while legitimacy involves a belief in rightful authority, trust reflects the public’s willingness to accept that authority in situations of uncertainty. Accordingly, in multilevel governance systems increasingly reliant on ADM, public trust becomes a critical factor in determining whether legitimacy is recognised, internalised, or contested.

To that end, this paper draws on both philosophical and legal literature to distinguish between legitimacy—understood as the normative justification of authority—and trust—conceived as the lived response to institutional behaviour, particularly under conditions of opacity and reduced contestability. While Danaher cautions against a legitimacy crisis stemming from diminished human involvement in algorithmic systems, this paper builds on his analysis by examining how trust is perceived and contested in AI-assisted justice, especially when stakeholders cannot easily understand or challenge decisions made by such systems.

The paper engages with ongoing debates in legal theory that often treat trust as secondary to more foundational principles such as justice or legitimacy. Rather than substituting trust for these concepts, the article contends that trust offers a valuable lens through which to understand how legitimacy is recognised, internalised, or rejected by members of the public—particularly in multilevel governance systems where AI tools operate with varying degrees of transparency. Within this context, the paper proposes an exploratory and analytical tool: the TRUST framework, which stands for Transparency, Responsibility, Understanding, Social justice, and Timely oversight. This framework is intended as an interpretive guide for institutional design and assessment when integrating AI systems into the judiciary.

The structure of the paper is as follows: First, it introduces the concept of algocracy and its explores its implications for legal authority. Second, it develops a theoretical discussion of trust, trustworthiness, and legitimacy in judicial systems, incorporating examples and case studies to illustrate both the potential benefits and risks of incorporating AI. Third, it presents the TRUST framework and demonstrates how its principles align with current judicial processes and principles of fairness, transparency, and human judgment. Finally, the conclusion reflects on the limitations of a trust-cantered approach while reaffirming its value in navigating the normative and practical tensions that AI and ADM systems introduce into the judiciary.

By combining theoretical analysis with normative reflection, this paper contributes to emerging debates on AI governance in judicial systems. It emphasises that without institutional commitments to transparency, accountability and inclusive oversight, the adoption of AI in judicial processes risks not only public trust but also the substantive legitimacy of the justice system.

Algocracy as the New Rule

The term algocracy comes from the combination of algorithm and kratia (Greek for “rule” or “power”). It refers to a system of governance or decision-making in which algorithms play a central role in shaping and executing policies, often with reduced human intervention. The concept emerged in the early 2000s, as scholars started to engage with the societal implications of increasing data-driven and automated decision processes.

Sociologist Aneesh (2009) first coined the term algocracy to describe systems in which computer-programmed algorithms structure and constrain human interaction with decision-making processes. This initial conception laid the groundwork for future discussions about algorithmic governance (Williamson 2015). However, it was Danaher’s 2016 article, “The Threat of Algocracy: Reality, Resistance and Accommodation”, that brought the concept into sharper focus. Danaher explored the moral and political implications of algorithmic governance, defining algocracy as “the phenomenon whereby algorithms take over public decision-making systems” (2016, 247). He emphasises that algocracy is not about computers or artificial agents seizing control of government bodies to serve their own interests. Rather, it refers to the increasing use of algorithmic systems to structure decision-making in ways that limit human input and contestability.

Danaher’s concern lies with the legitimacy of these systems. He warns that by reducing opportunities for meaningful human participation and deliberation, algocratic systems threaten the foundations of democratic governance. He identifies two potential responses: resistance, which involves rejecting algorithmic systems altogether, and accommodation, which entails accepting their role while attempting to mitigate their negative effects (Danaher 2016). Yet, he argues that neither response fully addresses the problem without sacrificing other valuable aspects of decision-making, such as efficiency or consistency. His perspective is somewhat pessimistic, suggesting that we may be creating systems that limit human participation and control. This perspective underscores a governance paradox: algorithmic systems designed to optimize performance may inadvertently erode public trust by making decision processes less transparent, less explainable, and less human. Thus, while Danaher does not explicitly frame his argument in terms of trust, the issues he raises, such as the opacity and inaccessibility of algorithmic decision-making, have direct implications for public perceptions of institutional trust in legal settings.

The concept of algocracy is not simply a matter of presence or absence of algorithms; rather, it exists on a spectrum. This concept involves different forms of algorithmic governance, such as algorithmic regulation, where algorithms are employed to monitor, enforce, and modify behaviours (Yeung 2019); algorithmic governmentality, which shapes how individuals perceive and interact with the world (Rouvroy, Berns, and Carey-Libbrecht 2013); and data-driven decision-making, where big data and machine learning guide judicial rulings and policy decisions (Cantero Gamito and Ebers 2021). Within the judiciary, algocracy captures the increasing reliance on algorithms to monitor, regulate, and influence decision-making processes.

Judicial systems may experience varying degrees of algorithmic influence, ranging from minimal human oversight to fully automated judicial decision-making. Within the judiciary, these systems take multiple forms—from tools that assist judges with legal research to those that automate specific aspects of the decision-making process. Their legitimacy is not solely a matter of institutional design or legal compliance, but also of how citizens, legal professionals, and broader communities experience and evaluate them. As Popelier et al. (2022) argue, trust must be analysed at multiple levels—individual, organisational, and systemic—and in relation to specific actors and actions. While the scholarly discourse on algocracy focuses on macro-level consequences, such as data protection, surveillance, and bias, this paper builds on Danaher’s concerns while shifting the analytical focus toward trust as a dynamic lens through which the legitimacy of algocratic systems is interpreted and negotiated in practice.

Public Trust Under Algocratic Rule

Trust is a multidimensional concept whose definition and scope vary across disciplines. In legal contexts, trust is closely associated with principles of legitimacy and procedural fairness, where citizens rely on institutions to uphold laws impartially and consistently (De Brito Duarte et al. 2023). From a social perspective, trust is understood as the glue of relationships and societal cohesion, defined by Fukuyama (1995) as the expectation that others in a community will act predictably and honour shared norms. In philosophy, Baier defines trust as “accepted vulnerability to another’s possible but not expected ill will” (1986, 235) emphasising the relational and moral dimensions of dependency. In the technical field, trust is often associated with the reliability, explainability, and security of systems. From a political standpoint, trust constitutes a rational expectation that institutions and leaders will act in the public interest (Hardin 2002). These varying disciplinary perspectives underscore a common insight: trust is not reducible to a binary status or static attribute. Collectively, these perspectives present trust as a dynamic and context-sensitive construct—fundamental to the effective functioning of relationships, institutions, and systems. In judicial systems, particularly those integrating AI and ADM, the relational and contextual dimensions of trust become especially salient.

The distinction between trust and trustworthiness is crucial for understanding the dynamics of judicial systems. Trustworthiness represents an institution’s objective capacity to deserve trust, while trust is the subjective willingness of individuals to be vulnerable to the actions of that institution (Hardin 2002). Drawing on Annette Baier’s definition of trust, one could say that citizens accept vulnerability to judicial decisions, believing in the system’s just and impartial exercise of power (Purves and Davis 2022). This belief is grounded in assumptions about institutional competence (e.g., legal knowledge, procedural consistency), integrity (e.g., impartiality, non-discrimination), and benevolence (e.g., public-serving motivations)—criteria that collectively underpin institutional trustworthiness (Popelier et al. 2022; Wallace and Goodman-Delahunty 2021).

Further nuance is added by Karen Jones’ (2012) theory of three-place of trustworthiness, which provides a useful lens for institutional analysis. According to Jones, trustworthiness encompasses three key elements. First, competence, understood as the knowledge, skills, and capabilities of judges, lawyers, and other legal professionals to interpret and apply the law accurately and fairly. Second, the motivational requirement, which concerns the reasons judicial actors behave in trustworthy ways. Ideally, this motivation stems from a genuine commitment to justice and the public good, rather than by fear of sanction or self-interest. Third, domain specificity, which recognises that trustworthiness is context-dependent and must be evaluated within the specific institutional setting in which it is exercised (Jones 2012).

Therefore, public trust—rather than trustworthiness alone—serves as a valuable lens through which to examine how legitimacy is experienced in contexts where AI and automation mediate decision-making (Pakulski 2017). Unlike trustworthiness, which focuses on institutional qualities, trust captures how institutions are perceived by individuals and societies navigating opaque, technocratic systems. By foregrounding public trust as a relational and perceptual phenomenon, this research underscores how the use of AI in the judiciary shapes citizens’ experience of legitimacy, fairness, and due process—often in ways that may not be addressed by traditional legal guarantees alone.

Levels of Trust in Judicial Systems

Trust in judicial institutions possesses distinctive characteristics that set it apart from interpersonal or interorganisational trust. While interpersonal trust involves known actors and specific interactions, trust in courts is shaped by abstract expectations and symbolic commitments (Purves and Davis 2022; Wallace and Goodman-Delahunty 2021). Judicial trust is fundamentally impersonal, often resting on faith in abstract systems and processes rather than in specific individuals (Bayer 2024). In addition, it is marked by a systemic reliability, meaning that public trust is largely rooted in the perceived dependability and consistency of the judicial system as a whole, rather than on the trustworthiness of individual judges or court officials (Fine and Marsh 2024). Judicial trust also has a symbolic representation, as courts are seen to embody core societal values such as equality and justice. Public trust is shaped by the extent to which judicial institutions are perceived to uphold these values (Bayer 2024). The judiciary’s ability to represent and defend these core societal values plays a crucial role in maintaining public trust. Finally, judicial trust is grounded in procedural justice, wherein trust is closely tied to perceptions of procedural fairness (Cram 2024). Even unpopular rulings may be accepted if processes are seen as fair, transparent, and consistent.

Taken together, these features demonstrate that trust in the judiciary is not solely outcome-based; rather, it is deeply rooted in how processes are experienced and interpreted (Pakulski 2017). This becomes especially salient in the age of algocracy, where procedural opacity and diminished human involvement can undermine this interpretive trust. This trust rests on two fundamental pillars: competence and integrity (Svare, Gausdal, and Möllering 2020). Competence is understood as the judiciary’s ability to apply the law reliably, while integrity denotes the assurance of impartial and fair treatment (Bayer 2024; Mayer, Davis, and Schoorman 1995). Public trust is not only essential to judicial legitimacy—it is also a precondition for the judiciary’s effective functioning. When trust in judicial institutions erodes, the consequences may include noncompliance, public resistance, and institutional weakening, all of which pose serious risks to the rule of law.

Therefore, far from being a monolithic concept, this research argues that public trust in the judicial system operates across three distinct yet interconnected levels—shaped by a complex interplay of factors. These range from individual perceptions of fairness and societal expectations of justice to organisational integrity and the impact of technological advancements. This multifaceted character renders the landscape of judicial trust both dynamic and diverse.

Algorithmic Decision-Making in the Judiciary: A Trust Centered Perspective

The integration of AI and ADM systems into the judiciary marks a new era of governance, enhancing efficiency and addressing challenges in areas such as e-discovery, document review, predictive analytics, risk assessment, and dispute resolution (Stankovich et al. 2023). In practice, courts have implemented AI tools for automated anonymisation and metadata recognition in document management (Terzidou 2023). These AI-driven approaches have transformed public service delivery by streamlining tasks like data anonymisation and document translation, improving the accurate identification of natural and legal persons, addresses, and roles. Crucially, these systems aim to preserve the comprehensibility of legal cases while safeguarding personal data (Gaspar and Curzi de Mendonça 2021).

The growing presence of ADM in judicial contexts raises normative and procedural concerns. Beyond efficiency, we must critically assess how these systems interact with foundational principles such as due process, accountability, and public trust. This section analyses the concept of trust as a complementary and necessary lens through which to understand how ADM affects perceptions of legitimacy in judicial settings. While trust refers to the subjective willingness to accept vulnerability, and legitimacy to the rightful exercise of authority, the two are deeply interrelated. Accordingly, this section explores how various ADM technologies intersect with three levels of public trust: individual, societal, and institutional.

The Algorithmic Lifecycle and Vulnerabilities to Trust

The algorithmic lifecycle provides a framework for identifying the sources of, and strategies to mitigate, outcomes that may conflict with fundamental rights (Laato et al. 2022). While different versions of the algorithmic lifecycle exist, it is commonly divided into three broad stages: the design of the algorithmic system, its integration within an organisation, and its application in decision-making processes (Marabelli, Newell, and Handunge 2021). In this regard, Azzutti, Ringe, and Stiehl (2023) have demonstrated that adverse outcomes related to fundamental rights often arise from unaddressed risks at different stages of the algorithmic lifecycle. This paper focuses on the third stage, where unaddressed design flaws and poor organisational integration can undermine the quality of decisions (Marabelli, Newell, and Handunge 2021). For example, when opaque and discriminatory algorithmic profiling systems are deployed without meaningful human oversight, they may lead to systematically discriminatory outcomes (Haitsma 2023).

The third stage of the AI lifecycle intersects with Danaher’s theory of algocracy, wherein algorithms diminish human oversight, restrict contestability, and risk displacing meaningful human engagement (2016). As Yu and Li (2022) note, opacity at this stage fosters epistemic dependence, which, combined with a lack of explainability, erodes public trust. Danaher’s concern that algocracy could limit human participation and understanding resonates with the challenges at this stage of the lifecycle, where unresolved design flaws and poor organisational integration may lead to decisions that are neither transparent nor easily challengeable. These dynamics reinforce the risks of algocratic governance.

Two aspects are crucial at this stage: explainability and control1. First, the capacity to explain, justify, and provide transparency around the decision-making process—and the role played by algorithmic systems—is essential for safeguarding individuals’ fundamental rights (Yeung et al. 2021). Second, effective control mechanisms—such as continuous oversight, evaluation, maintenance, and regular revision—of the AI system are indispensable. These include monitoring system performance, correcting errors, and updating the system to adapt to evolving legal standards and technological advancements. These mechanisms are necessary to ensure the long-term reliability and effectiveness of AI-powered tools and to establish a feedback loop that informs improvements in design, implementation, and application (Veluwenkamp and Hindriks 2024). Absent robust practices in either area, risks such as systemic discrimination may go unchecked—ultimately eroding public trust at individual, societal, and institutional levels.

ADM Use and the Three Levels of Trust

AI systems can be used to inform, enhance, or even fully replace judicial discretion, depending on their design and the level of human oversight deemed necessary. This oversight can range from human or technological intervention at various stages (human-in-the-loop) to full autonomy (Bennett Moses et al. 2022). While predictive models are commonly employed to estimate litigation outcomes or support administrative triage, their integration into judicial processes raises significant concerns regarding transparency, due process, and the safeguarding of legal guarantees (Meyer-Resende and Straub 2022).

To date, the most advanced applications of AI have been implemented in areas adjacent to judicial decision-making—such as administrative adjudication, document analysis, and procedural support. However, attempts to automate judicial processes, including judges’ decision-making roles, remain at an early stage (Barysė and Sarel 2024). The following typology maps different ADM applications to three interrelated levels of trust—individual, institutional, and societal—to evaluate how these technologies may affect the public’s willingness to accept judicial authority in algorithmically mediated settings.

To better illustrate how different types of ADM systems intersect with various levels of public trust—and the legal risks they may entail—the following table summarises the key examples discussed in this section. It classifies each system by its primary function, impact on trust, and potential human rights and legitimacy concerns.

Table 1. Typology of AI and ADM systems in the judiciary based on trust levels

|

Case/System |

Level of trust affected |

Type of AI/ADM function |

Risks to Human Rights |

Threatened Principle |

|

EXPERTIUS(Mexico) |

Institutional |

Advisory decision-support |

Minimal, supports consistency |

Due process |

|

BASS(Australia) |

Institutional |

Risk assessment/coordination |

Potential bias if data is flawed |

Fairness, transparency |

|

Frauke and Olga(Germany) |

Institutional |

Automated case triage and settlement proposals |

Low if oversight is maintained |

Accountability, efficiency |

|

ChatGPT use(Colombia) |

Individual |

Information retrieval |

Opacity, unverified outputs |

Transparency, procedural justice |

|

ChatGPT use(Netherlands) |

Individual |

Information retrieval |

Opacity, no disclosure |

Transparency, contestability |

|

SyRI(Netherlands) |

Societal |

Autonomous risk profiling |

Discrrimination, privacy violations |

Non-discrimination, privacy, due process |

|

Udbetaling Danmark (UDK)(Denmark) |

Societal |

Autonomous fraud detection |

Discrimination, lack of accountability |

Equality, due process, legality |

|

Gotham Predictive Policing (Germany) |

Societal |

Predictive policing |

Over-surveillance, lack of due process |

Informational self-determination, accountability |

Source: Author.

This typology illustrates how different ADM systems intersect with distinct levels of public trust, revealing both their functional roles and the specific risks they pose to legal principles. By clarifying where and how these technologies operate, the table maps the fields in which trust must be cultivated and maintained. Beckman, Hultin Rosenberg, and Jebari (2024) argue that democratic legitimacy rests on a double requirement of reason-giving and accessibility where public decisions must remain faithful to democratically authorised ends and provide intelligible explanations to those subject to them. When either criterion fails, legitimacy is compromised and the relational trust that depends on it erodes. This insight underpins the later claim that transparency and explainability are not mere design preferences but pre-conditions for warranted public trust in algocratic courts.

In this context, the judiciary’s role as guardian of individual rights and societal stability hinges on balancing technological innovation with the irreplaceable human elements of judicial decision-making. Sustaining public trust in this era of algocracy will require more than just improving the transparency and explainability of algorithmic tools; it also demands the preservation of human judgment, reasoning, and ethical deliberation within the justice system (Zerilli et al. 2019). Only by striking this balance can the judiciary uphold its role in safeguarding individual rights and societal stability (Kinchin 2024). Ultimately, citizens’ belief in the judiciary’s capacity to deliver impartial and ethical decisions remains essential, regardless of external pressures or technological influences.

The integration of AI-driven tools into judicial processes introduces challenges to this balance. Automated systems—already used in areas such as bail determinations, sentencing, and even judicial reasoning—often lack transparency, raising concerns about fairness and undermining public confidence in judicial accountability (Kolkman et al. 2024). Continuing the analysis of the interconnected levels of trust, it becomes evident that this interconnectivity is reflected in certain cases and applications.

Individual Trust and Search/Drafting Tools

Trust at the individual level is inherently relational and context specific. Drawing on Baier’s (1986) definition, trust entails a willingness to become vulnerable to the discretionary actions of another, often in situations lacking full control or complete information. In judicial contexts, this vulnerability is especially pronounced, as individuals are subject to authoritative decisions that can materially affect their rights, freedoms, and reputation (Hough, Jackson, and Bradford 2013). When such decisions are mediated or shaped by algorithmic systems, the basis for trusting the process becomes more precarious—particularly when the underlying mechanisms are opaque, poorly explained, or inconsistently applied.

Cases from Colombia and the Netherlands demonstrate how algorithmic opacity can directly undermine individual trust in judicial systems. In Colombia, a Circuit Court judge incorporated responses from ChatGPT into a ruling concerning a minor with autism spectrum disorder, prompting a review by the Constitutional Court. Although the Court concluded that the use of ChatGPT in this instance did not violate due process, it emphasised that AI should not replace human judicial decision-making and outlined criteria for its appropriate use, including accountability, adherence to legality, and suitability. The Court highlighted that AI cannot substitute for a judge’s duty to assess evidence, provide legal reasoning, and uphold procedural rights (Constitutional Court of Colombia 2024).

In the Dutch case, a judge used ChatGPT to gather information on the lifespan of solar panels and electricity costs during a dispute between homeowners (Gelderland District Court 2024). The District Court incorporated ChatGPT’s responses into its ruling, specifically to estimate the average lifespan of solar panels and the current average price of electricity. Unlike the Colombian case, the Dutch judge did not provide the specific prompts or responses exchanged with ChatGPT, raising concerns about transparency and the verification of AI-generated information in judicial proceedings. In both examples, the lack of procedural clarity affected how trust in the process could be built or sustained.

These cases illustrate how algocratic conditions—where decision-making is structured by opaque computational logic—can erode the foundations of trust. Even when outcomes are legally valid, individuals may feel alienated or disempowered if they cannot understand how a decision was made or whether it involved genuine deliberation (Perona and Carrillo de la Rosa 2024). Key risks to individual trust in AI-assisted judicial decision-making include a lack of clarity about AI’s role, which fosters suspicion and disengagement; inconsistent or unverifiable outputs, which undermine the perceived reliability of decisions; and the absence of disclosure mechanisms, which limits individuals’ ability to understand or contest AI influence. In such environments, trust is not merely difficult to build—it is structurally undermined by design.

At the individual level, the opacity of AI systems can foster scepticism among citizens engaging with the judicial system (Cheong 2024). This reflects Baier’s notion of trust as “accepted vulnerability,” wherein the absence of transparency in AI decision-making processes diminishes individuals’ willingness to submit to judicial outcomes. Key risks to individual trust in AI ADM include the lack of clarity surrounding the role of AI in judicial reasoning, which can lead to disengagement when users or litigants are uncertain about how decisions are shaped. Additionally, generative tools may produce outputs that appear plausible but are ultimately incorrect or unverifiable, undermining confidence in the perceived reliability of such decisions. Finally, the absence of procedural requirements for declaring the use of AI—such as judicial declarations—prevents individuals from understanding, contesting, or verifying the role of algorithmic tools in legal outcomes. This lack of transparency and accountability ultimately weakens the conditions necessary for sustaining public trust.

An example illustrating the interplay between individual trust and AI adoption is CitizenLab’s civic technology platform in Belgium (Sgueo 2020). Designed to process and analyse public input using ML algorithms, the platform demonstrates AI’s potential to enhance decision-making processes. In one case, the Youth4Climate platform analysed thousands of public contributions, using AI to identify priorities and produce actionable policy recommendations. The platform’s success was contingent on integrating AI into existing workflows (Karhu, Häkkilä, and Timonen 2019).

Danaher’s theory could thus be extended to include an additional concern: the overreliance on technology—particularly AI—which risks significantly undermining individual trust in judicial systems. Algocracy disrupts the traditional interpersonal and procedural bases of trust by replacing deliberative transparency with systemic opacity. To sustain individual trust, judicial systems must go beyond ensuring the technical reliability of AI tools. They must also prioritize human accountability, explainability, and clear disclosure, reaffirming the justice system’s relational and ethical obligations to those it serves.

Institutional Trust and Assistance Tools

At the institutional level, trust is grounded in the judiciary’s capacity to deliver decisions that are consistent, impartial, and aligned with fundamental societal values such as fairness, equality before the law, and procedural regularity (Wallace and Goodman-Delahunty 2021). Institutional trust depends on systemic reliability, symbolic legitimacy, and perceived alignment with democratic values such as impartiality, transparency, and procedural justice. Within this framework, the careful integration of AI tools, designed to support rather than supplant human judgment, can help strengthen public confidence in judicial institutions.

International examples illustrate how algorithmic systems can bolster institutional trust when used to enhance administrative efficiency and consistency while maintaining normative legitimacy. In Mexico, the EXPERTIUS system advises judges and clerks on pension-related matters by offering standardised recommendations grounded in procedural rules and heuristic reasoning (Cáceres 2008), promoting uniformity without bypassing judicial interpretation. In Australia, the Judicial Commission of New South Wales introduced the Bail Assistant (BASS) program as a tool to guide coordination on bail decisions by aggregating contextual information and supporting social services, ensuring that individuals are not unnecessarily detained while awaiting trial (Bennett Moses et al. 2022; NSW Government 2024). In Germany, tools like the Frankfurt Electronic Judgment Configurator (Frauke) in the Frankfurt District Court and the OLGA trial assistant—co-developed by IBM—demonstrate how AI can assist in case grouping, schedule management, and settlement recommendations in bulk litigation without overstepping into autonomous judgment (Murrer 2023; CEPEJ 2024). Since settlement proposals do not legally bind the parties, AI can perform this task without raising concerns about constitutional validity.

AI adoption also reshapes internal trust dynamics within the judiciary, potentially creating conflicts between courts and among legal professionals at the organisational level. For instance, the introduction of AI tools for case prioritisation or automated decision support could lead to tensions if certain courts perceive these tools as undermining their autonomy or introducing inefficiencies due to poor implementation (Zimmermann and Lee-Stronach 2022). An inadequate adoption of AI tools may be seen as a faster, surface-level approach that fails to account for the complexities and needs at all levels of the judiciary, eroding institutional trust (Richards and Hartzog 2015). From a technical perspective, a seamless integration of AI systems into the judiciary’s existing technological infrastructure is essential. Interoperability plays a critical role, requiring systems to enable secure communication, efficient data exchange, and compatibility with existing software to avoid disruptions. Proper integration ensures scalability and prevents operational bottlenecks that could hinder the judiciary’s consistent application of laws.

These examples highlight a recurring feature: the tools are primarily designed to provide assistance and advice, functioning as support mechanisms rather than replacements for human judgment. In other words, these tools embody what Danaher (2016) refers to as a mode of accommodation within algocratic systems, accepting the role of algorithms in governance while designing safeguards that preserve human oversight. By introducing AI in assisting non-discretionary tasks such as data extraction, procedural guidance, and recommendation generation, these tools contribute to institutional trust in three key ways: they improve administrative efficiency, ensure procedural consistency, and maintain the judge’s ultimate authority in legal reasoning. Their effectiveness lies not only in performance but in public perceptions that judicial decisions remain human-led, transparent, and contestable. In this way, AI does not displace judicial reasoning but operates as a scalable support structure that supports the institutional resilience and legitimacy of courts working within complex, high-pressure environments.

Societal Trust and ADM System

At the far end of the algorithmic governance spectrum, lie fully ADM systems where AI operates with minimal human oversight. In these instances, the systems have been granted complete decision-making authority, often operating for extended periods without adequate scrutiny. Such implementations have resulted in adverse impacts on individuals due to the absence of transparency mechanisms and meaningful human control. This concern becomes even more pronounced when considering the growing reliance on machine learning (ML) models in legal prediction, which exemplifies how algorithmic systems can evolve from support instruments to de facto decision-makers, despite offering limited transparency or avenues for contestation.

ML models can, in principle, “predict” legal outcomes by identifying patterns and correlations within large volumes of historical case data. Earlier attempts relied on traditional statistical methods, correlating basic features of a case to its outcome, while modern techniques can detect more complex patterns (Krause, Perer, and Ng 2016). Unlike expert systems, which apply predefined legal rules to produce predictions, ML models learn from past examples and may incorporate diverse factors, including factual circumstances and the identities of judges and lawyers. Although some systems report high levels of accuracy—such as, predicting French Supreme Court rulings with 92% accuracy—, closer examination reveals that these results may not generalize to genuinely new cases (Bennett Moses et al. 2022).

While some highlight the potential of AI in the judiciary, recent research offers a more cautious perspective. Medvedeva and McBride (2023) show that only about 7% of Legal Judgment Prediction (LJP) studies predict outcomes as intended, despite reporting strong performance metrics, often due to oversimplified or inappropriate datasets. Similarly, Yassine, Esghir, and Ibrihich (2023) described how unique, context-specific factors, especially in complex or landmark cases, can render apparently “objectifiable” features.

However, the limitations of AI’s predictive capacity, especially in complex and context-sensitive legal settings, also signal broader implications beyond technical performance. These challenges extended into the concept of societal trust, where the legitimacy of judicial institutions is judged not only by their outcomes, but by their alignment with democratic norms and public expectations. Societal trust refers to the broader public’s collective confidence that legal institutions reflect and uphold shared democratic values such as equality, fairness, and accountability. Unlike interpersonal or institutional trust, societal trust is shaped by public discourse, media narratives, and visible, often high-profile cases2 of governance success or failure (Kinchin 2024). In the context of ADM, this form of trust is particularly vulnerable when algorithmic systems operate autonomously, with limited human oversight or transparency. Society may question whether AI systems have the necessary competence to make legal decisions, and whether their motivations align with human values of justice and fairness.

The cases of SyRI (System Risk Indication) in the Netherlands and the Udbetaling Danmark (UDK) in Denmark further illustrate the risks associated with opaque and autonomous ADM tools in public administration. Both systems were designed to detect social welfare fraud using algorithmic assessments but were drew criticism for their lack of transparency, discriminatory outcomes, and the absence of adequate safeguards (Amnesty International 2021). The Hague District Court ultimately ruled SyRI unconstitutional, citing disproportionate privacy intrusions and discriminatory targeting of low-income communities (Rechtbank Den Haag 2020). Similarly, the controversy surrounding Denmark’s welfare system revealed the use of vague and sensitive profiling criteria, flagging individuals with foreign affiliations under questionable legal grounds (Amnesty International 2024).

These examples underscore how failures in transparency, explainability, and contestability can produce profound legitimacy crises, fundamentally shaking public confidence in the justice system. In the UDK case, Amnesty International (2024) warned that the system’s opaque algorithms may constitute prohibited social scoring systems, or at the very least, qualify as high-risk AI systems requiring enhanced oversight and transparency measures. While the SyRI case revealed how lack of transparency and proportionality in ADM tools can violate due process and non-discrimination. Together, these cases affirm the need for robust safeguards, human oversight mechanisms, and legal accountability in ADM systems affecting public rights.

At the societal level, the concept of algorithmic justice demonstrates that such crises can have cascading effects. As Kinchin (2024) argues, different segments of society may perceive ADM tools as either enhancing fairness or entrenching systemic bias, depending on how visibly these systems align with democratic values. Another example of the interplay between social trust and AI adoption is the German Gotham system, in which the Federal Constitutional Court ruled against predictive policing tools for violating individuals’ right to informational self-determination (BVerfG 2023). Lack of clarity around data collection and processing practices not only impairs transparency but also undermines the public’s ability to hold institutions accountable.

This analysis of ADM in judicial systems reveals the multifaceted ways in which AI tools intersect with public trust. Mapping these interactions across institutional, societal, and individual levels has shown that trust is not a monolithic variable but a dynamic and layered construct, vulnerable to erosion when AI is deployed without sufficient transparency, human oversight and accountability. The cases mapped in Table 1 underscore this complexity, illustrating the wide range of ADM applications currently shaping judicial processes—from supportive advisory tools to autonomous decision-making systems. Thus, the future of algorithmic governance in the judiciary depends not only on technological design, but also on how well these systems are embedded within transparent, accountable, and ethically grounded institutional frameworks.

Crucially, the judiciary’s legitimacy does not depend solely on the legal soundness of its decisions but also on the public’s perception of procedural fairness, human discretion, and institutional integrity. The examined cases, from advisory systems like EXPERTIUS and BASS to fully autonomous systems like SyRI and UDK, highlight both the potential benefits and serious risks associated with ADM integration. When used in supportive roles, AI can reinforce institutional trust and procedural regularity. However, when opacity, lack of disclosure, or unchecked delegation dominate, the resulting epistemic dependence and overreliance pose structural threats to the legitimacy of judicial authority (Buijsman and Veluwenkamp 2023).

These risks are not abstract. They materialize in diminished public confidence, increased resistance to judicial outcomes, and, in extreme cases, systemic breakdowns in the rule of law (De Brito Duarte et al. 2023). The examples explored, ranging from the algorithmic overreach of SyRI in the Netherlands and UDK in Denmark to the transparency lapses in generative AI use in Colombia and the Netherlands, demonstrate how ADM systems can erode public trust when implemented without sufficient procedural safeguards. In contrast, supportive tools like EXPERTIUS, BASS, and OLGA show that AI can enhance institutional trust when designed to augment, rather than replace, human judgment.

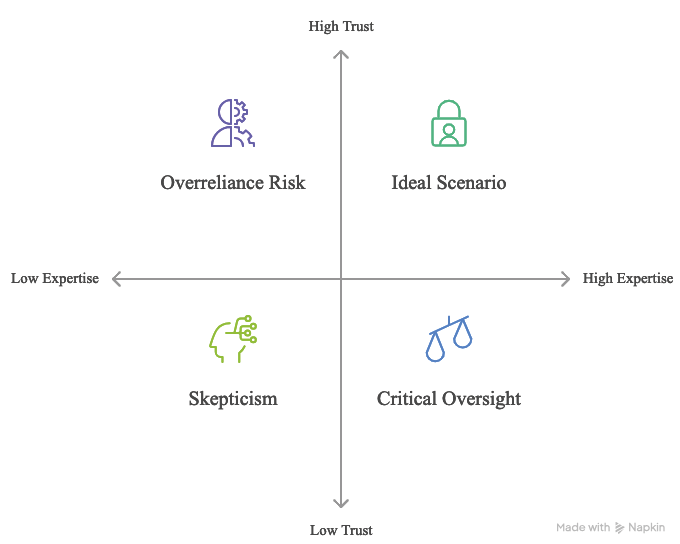

Accordingly, ADM systems must be designed with context-sensitive safeguards that recognize trust not merely as a byproduct of legitimacy but as its operational condition. Following the insights of Popelier et al. (2022) on multilevel trust and building on Danaher’s theory of algocracy, this analysis affirms that the legitimacy of ADM in judicial contexts depends on preserving the relational elements of trust: meaningful human oversight, transparent reasoning, and the symbolic authority of courts. As illustrated in Figure 1, achieving a trustworthy AI ecosystem in judicial settings requires balancing levels of public trust with institutional and individual expertise. Each quadrant underscores a different governance posture, from ideal conditions to the risks of overreliance or scepticism, demonstrating why critical oversight must accompany increased reliance on algorithmic systems. Such safeguards are essential not only for maintaining system accountability but also for protecting human rights and preserving trust.

Source: Image generated by Napkin AI based on the author-provided text description, depicting the diverse scenarios of trust and experience in AI systems showing the undesirable outcomes of overreliance and dependency created on November 15th, 2024.

Figure 1 complements the typology presented in Table 1 by mapping the interplay between levels of trust and expertise in the governance of AI systems. For instance, the UDK case represents a high-trust, low-expertise scenario, illustrating the overreliance risk quadrant, where confidence in the system coexists with insufficient scrutiny or verification. In contrast, systems like Frauke/OLGA, when deployed under strong oversight, may align with the ideal scenario of high trust and high expertise. Through its visual representation of these dynamics, Figure 1 helps contextualize the institutional conditions under which ADM tools either reinforce or erode judicial legitimacy.

To mitigate the dangers of technocratic drift and epistemic overreliance, judicial systems must adopt a proactive and principled approach to AI integration. This includes implementing transparent procedural disclosure requirements to ensure that the use of AI in judicial rulings is visible and contestable (Colombi Ciacchi et al. 2025). It also requires the establishment of independent oversight bodies empowered to audit algorithmic tools and review potentially contested outcomes. Moreover, continuous training for judges and legal professionals in AI literacy and ethical application is essential to promote responsible use and informed scrutiny. Finally, an enduring institutional commitment to the foundational principles of fairness, non-discrimination, and due process is critical to preserving public trust and upholding the legitimacy of judicial authority in an increasingly algorithmic environment.

Thus, rather than abandoning technological progress, the judiciary must learn to govern it strategically. A trust-cantered framework that distinguishes yet interrelates individual, societal, and institutional levels can serve as both a diagnostic and a prescriptive tool to navigate this transformation. The goal is not to reject ADM, but to ensure that its deployment supports, rather than supplants, the values upon which judicial legitimacy and democracy itself ultimately rests.

Strengthening Public Trust in AI-Driven Judicial Systems

As has been discussed, the increasing integration of AI into judicial processes presents a critical challenge to the foundational principles of public trust in legal institutions. According to the 2023 EU Justice Scoreboard, public confidence in judicial systems remains fragile: only 11% of respondents rated them as ‘very good’ and 41% as ‘fairly good’ with considerable variations across member states (European Commission 2024). While countries like Finland and Denmark report high trust levels (83%), others such as Croatia and Poland scored lower (24-28%). These disparities, often influenced by political interference and individual experiences with justice systems, form a precarious baseline upon which the integration of AI technologies must carefully build or risk further eroding legitimacy.

The UNESCO global survey on the use of AI systems by judicial operators highlights that 44% of judicial operators have already incorporated AI tools into their work-related activities (Gutiérrez 2024b). This growing adoption raises questions about the preservation of judicial integrity and the maintenance of public trust. The potential for algorithmic bias, combined with the opacity of AI decision-making processes, creates a complex ecosystem of institutional vulnerability.

As judicial systems become more technologically augmented, concerns about explainability, accountability, and fairness intensify. For example, while predictive policing tools or AI-driven sentencing recommendations could provide consistent outputs, they often fail to account for the complexities of human judgment, leading to outcomes that feel dehumanised or unjust. This lack of transparency can amplify concerns about judicial independence and erode public trust, as AI tools might be perceived as overly deterministic or vulnerable to external manipulation.

To address these issues, this section introduces the TRUST framework as a normative anchor aimed at reinforcing public trust in AI-driven judicial systems. TRUST stands for: Transparency, Responsibility, Understanding, Social justice, and Trustworthy oversight. This framework does not replace the legal foundations of legitimacy but complements them by grounding the relational and procedural dimensions of trust. As previously illustrated in Table 1, different ADM systems operate across trust levels and carry distinct risks. The TRUST framework offers a corresponding evaluative lens, enabling judicial institutions to align technological functionalities with the procedural safeguards illustrated in Figure 1.

First, the Transparency factor demands open, accessible information about how AI systems function and influence decisions. Algorithmic tools used in judicial settings, such as bail decisions or case prioritisation, must provide clear and comprehensible justifications for their outputs and be subject to meaningful public scrutiny (Felzmann et al. 2020). The failures of systems like the UDK and the SyRI cases illustrate the risks of insufficient transparency and public notification, underscore the need for procedural clarity and the right to an effective remedy. In Denmark, Amnesty International (2024) highlighted that fraud detection algorithms lacked independent oversight, transparency in operations, and mechanisms to notify individuals about automated processes. Similarly, the Netherlands demonstrated how secretive algorithmic practices undermined the right to effective remedy and disproportionately harmed marginalised populations through informational asymmetry. To prevent the recurrence of such harms, judicial authorities must institutionalize mechanisms such as public registries, procedural notifications, and transparency reports. These should clearly outline the purposes, mechanisms, and impacts of algorithmic systems, alongside robust accountability frameworks. By making the deployment of AI visible and contestable, these measures reinforce the foundational principle that justice must not only be done, but must also be seen to be done.

Second, Responsibility requires strong explainability and human oversight to ensure that algorithms do not override ethical deliberation or individualised consideration (Veluwenkamp and Hindriks 2024). For instance, while an AI tool might flag an individual as a flight risk during a bail hearing, the final decision should rest with a judge who can evaluate contextual factors beyond the algorithm’s scope. Maintaining this balance requires the development of formal protocols delineating the scope of algorithmic advice, as well as institutional structures that support oversight, such as internal review bodies or external audit committees (Kolkman et al. 2024). As Ceva and Jiménez (2022) argue, answerability involves not only of explaining decisions but also taking responsibility for them, stripping institutions of meaningful accountability. Responsibility thus becomes both a normative and a procedural requirement, ensuring that technological expediency does not override ethical judgment. These frameworks should include independent auditing processes, continuous evaluations of AI models for fairness and bias, and clearly defined protocols for addressing errors or unintended outcomes (Alvarez et al. 2024).

Third, Understanding focuses on education and AI literacy for legal professionals and the public. Judges and court administrators must know how AI tools operate, recognize their potential biases, and critically evaluate their outputs and limitations (Gutiérrez 2024b). This is particularly important in cases involving generative AI, such as the use of ChatGPT in judicial rulings in Colombia and the Netherlands. In both cases, the absence of clear procedural guidelines and the limited understanding of the tool’s capabilities and risks resulted in controversial decisions that weakened public trust (Flórez Rojas 2024). Enhancing AI literacy among legal professionals bridges the gap between technological advancements and judicial expertise, ensuring AI systems are employed responsibly and effectively. Thus, understanding the distinction between these tools and their appropriate applications in judicial contexts is essential. To maintain institutional credibility, developing AI literacy among judicial professionals must involve a multidimensional approach. This includes value-sensitive design, continuous ethical training, and the creation of robust frameworks that balance technological efficiency with substantive legal reasoning (Díaz-Rodríguez et al. 2023). Thus, judges should be empowered not merely as users of technology but as critical interpreters of algorithmic outputs, ensuring that AI tools enhance the principles of justice.

Fourth, Social justice extends the framework beyond procedural concerns to address the broader normative landscape within which AI is deployed. Public perceptions of judicial legitimacy are shaped by both individual experiences and broader societal evaluations of fairness and procedural justice. Algorithmic tools that operate without consideration for cultural, historical, or institutional contexts risk entrenching the very disparities they are meant to resolve (Fine and Marsh 2024). For instance, ADM systems trained on skewed data may disproportionately affect minority groups or reinforce patterns of exclusion. To mitigate these risks, AI integration must be guided by equity impact assessments, participatory design involving affected communities, and an ongoing commitment to fairness as a substantive value. In doing so, the judiciary acknowledges that public trust is not merely a matter of technical accuracy but of moral alignment with democratic values.

Finally, Trustworthy oversight involves the institutional mechanisms necessary to ensure that algorithmic governance in the judiciary remains transparent and accountable. This includes the establishment of independent bodies empowered to audit AI systems, evaluate their compliance with legal standards, and intervene in cases of malfunction or abuse (Díaz-Rodríguez et al. 2023). The EU AI Act emphasises the need for accessible, comprehensible explanations of algorithmic decisions, ensuring they align with principles of fairness and accountability (Reisman et al. 2018). Within judicial institutions, these requirements translate into practices such as publishing algorithmic transparency reports, conducting post-implementation reviews, and maintaining channels for public and professional feedback. Beckman, Hultin Rosenberg, and Jebari argue that ML systems become democratically illegitimate when they displace the practice of reason-giving or embed decisions in inaccessible code. Their proposed remedy is to embed ML “in an institutional infrastructure that secures reason-giving and accessibility” (2024, 982). Such oversight not only strengthens institutional resilience but also affirms the judiciary’s role as a guardian of rights in the digital age.

Taken together, the TRUST framework provides a structured yet adaptable model for embedding trust-cantered values into AI governance. It recognises that trust is not a passive byproduct of legal authority, but an active condition of its legitimacy—especially when decisions are increasingly mediated by opaque, complex technologies. Rather than positioning trust as a mere derivative of legitimacy, this framework treats it as a dynamic precondition for public acceptance and institutional resilience. As illustrated by Table 1, ADM systems vary significantly in their functions, risks, and impacts across levels of trust. Embedding the TRUST principles offers a path to mitigate the harms of opaque autonomous decision-making while enhancing the judiciary’s capacity to uphold the rule of law in a digital age.

Conclusions

This paper has examined the integration of algorithmic decision-making systems in judicial processes through the analytical lens of algocracy, emphasising how such technological transformations affect public trust and institutional legitimacy. Building on Danaher’s foundational critique, the study explores AI in the judiciary not merely as a technical evolution, but as a potential shift in the normative underpinnings of adjudication. It shows that algorithmic tools increasingly structure decision-making processes, such as decision-support tools and predictive analytics, they risk displacing the human-centric, deliberative nature of legal judgment, with implications for transparency, accountability, and fairness.

By mapping ADM technologies against three levels of public trust—individual, institutional, and societal—the paper provides a diagnostic framework to assess how algorithmic governance affects the public’s willingness to accept judicial authority. Case studies such as EXPERTIUS (Mexico), BASS (Australia), and OLGA (Germany) demonstrate that AI can enhance procedural consistency and institutional efficiency when embedded within clear oversight frameworks. Conversely, the SyRI system in the Netherlands and the UDK model in Denmark exemplify how opacity, lack of contestability, and perceived discrimination can trigger public backlash, judicial invalidation, and legitimacy crises. These risks are not hypothetical: they manifest in diminished citizen confidence, resistance to legal decisions, and systemic erosion of the rule of law.

The paper advances the TRUST framework—Transparency, Responsibility, Understanding, Social justice, and Trustworthy oversight—as a normative guide for judicial institutions seeking a responsible integration of AI. This framework does not displace traditional legal standards of legitimacy but complements them by foregrounding the relational and procedural dimensions of trust that are increasingly salient in AI-mediated governance. It provides a conceptually integrated and academically grounded model for evaluating and strengthening public trust under emerging conditions of algorithmic decision-making in the judiciary.

The judiciary’s response to these technological advancements has been far from consistent. While many legal systems express a clear commitment to digitalisation and AI integration, persistent resistance often reflects concerns about safeguarding judicial independence, upholding due process, and retaining the human dimension of legal decision-making. The findings reveal that legitimacy in AI-assisted judicial systems cannot be sustained solely by legal formalism or technical performance. High accuracy, for instance, does not compensate for a lack of explainability, nor can efficiency override the need for meaningful human judgment. As the analysis of predictive tools and generative AI use illustrates, overreliance on opaque technologies without clear disclosure mechanisms undermines the public’s ability to contest or understand decisions that directly affect their rights.

Many jurisdictions have adopted a measured approach, using AI for support and administrative tasks rather than for core decision-making. This aligns with Danaher’s concept of “accommodation,” meant to meaningfully incorporate AI while preserving human oversight and decision-making authority. Yet the continued expansion of algorithmic authority brings with it a deeper, systemic threat: the erosion of public trust. This dimension of algocracy—less visible than concerns over accountability or legal validity—is no less fundamental. Trust is not simply a byproduct of legitimacy; it is one of its operational conditions.

Looking ahead, the judiciary must avoid drifting toward automation for its own sake and instead foster institutional resilience by embedding AI within transparent, accountable, and ethically grounded frameworks. This requires deliberate governance strategies: public-facing disclosures, independent oversight of bodies, ongoing training for legal professionals, and inclusive policymaking that reflects the plural values of justice. A trust-centred approach offers both a diagnostic and prescriptive lens for navigating the algorithmic turn in judicial governance, ensuring that technological innovation enhances, rather than erodes, the democratic foundations of law.

References

- Alvarez, Jose M., Alejandra Bringas Colmenarejo, Alaa Elobaid, Simone Fabbrizzi, Miriam Fahimi, Antonio Ferrara, et al. 2024. “Policy Advice and Best Practices on Bias and Fairness in AI”. Ethics and Information Technology 26 (31): 1-26. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10676-024-09746-w

- Amnesty International. 2021. Xenophobic Machines: Discrimination through Unregulated Use of Algorithms in the Dutch Childcare Benefits Scandal. London: Amnesty International Ltd. https://www.amnesty.org/en/documents/eur35/4686/2021/en/

- Amnesty International. 2024. Denmark: Coded Injustice: Surveillance and Discrimination in Denmark’s Automated Welfare State. London: Amnesty International Ltd. https://www.amnesty.org/en/documents/eur18/8709/2024/en/

- Aneesh, Aneesh. 2009. “Global Labor: Algocratic Modes of Organization”. Sociological Theory 27 (4): 347-370. https://doi.org/10.1111/J.1467-9558.2009.01352.X

- Azzutti, Alessio, Wolf-Georg Ringe, and H. Siegfried Stiehl. 2023. “Artificial Intelligence in Finance: Challenges, Opportunities and Regulatory Developments”. In Artificial Intelligence in Finance: Challenges, Opportunities and Regulatory Developments, edited by Nydia Remolina and Aurelio Gurrea-Martinez, 198-242. London: Edward Elgar Publishing Ltd. https://doi.org/10.4337/9781803926179

- Baier, Annette. 1986. “Trust and Antitrust”. Ethics 96 (2): 231-260. https://doi.org/10.1086/292745

- Barysė, Dovilė, and Roee Sarel. 2024. “Algorithms in the Court: Does It Matter Which Part of the Judicial Decision-Making Is Automated?”. Artificial Intelligence and Law 32 (1): 117-146. https://doi.org/10.1007/S10506-022-09343-6

- Bayer, Judit. 2024. “Post-Truth and Post-Trust: How to Re-Define Trust in the Judicial System and the Media”. ERA Forum 25 (2): 165-179. https://doi.org/10.1007/S12027-024-00795-8

- Beckman, Ludvig, Jenny Hultin Rosenberg, and Karim Jebari. 2024. “Artificial Intelligence and Democratic Legitimacy: The Problem of Publicity in Public Authority”. AI & Society 39 (2): 975-984. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00146-022-01493-0

- Bennett Moses, Lyria, Monika Zalnieriute, Michael Legg, Felicity Bell, and Jake Silove. 2022. “AI Decision-Making and the Courts: A Guide for Judges, Tribunal Members and Court Administrators”. Research Reports. Sydney: The Australian Institute of Judicial Administration Limited (AIJA). https://aija.org.au/publications/ai-decision-making-and-the-courts-a-guide-for-judges-tribunal-members-and-court-administrators/

- Buijsman, Stefan, and Herman Veluwenkamp. 2023. “Spotting When Algorithms Are Wrong”. Minds and Machines 33 (4): 541-562. https://doi.org/10.1007/S11023-022-09591-0

- BVerfG. 2023. Judgment of the First Senate of 16 February 2023 -1 BvR 1547/19-, paras. 1-178. https://www.bverfg.de/e/rs20230216_1bvr154719en

- Cáceres, Enrique. 2008. “EXPERTIUS: A Mexican Judicial Decision-Support System in the Field of Family Law”. In Legal Knowledge and Information Systems, edited by Enrico Francesconi, Giovanni Sartor, and Daniela Tiscornia, 78-87. https://doi.org/10.3233/978-1-58603-952-3-78

- Cantero Gamito, Marta, and Martin Ebers. 2021. “Algorithmic Governance and Governance of Algorithms: An Introduction”. In Algorithmic Governance and Governance of Algorithms. Legal and Ethical Challenges, edited by Martin Ebers and Marta Cantero Gamito, 1-22. Cham: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-50559-2_1

- CEPEJ (European Commission for the Efficiency of Justice). 2024. European Judicial Systems. CEPEJ Evaluation Report. Part 1 General Analyses. Strasbourg: Council of Europe. https://rm.coe.int/cepej-evaluation-report-part-1-en-/1680b272ac

- Ceva, Emanuela, and María Carolina Jiménez. 2022. “Automating Anticorruption?”. Ethics and Information Technology 24 (48): 1-14. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10676-022-09670-x

- Cheong, Ben Chester. 2024. “Transparency and Accountability in AI Systems: Safeguarding Wellbeing in the Age of Algorithmic Decision-Making”. Frontiers in Human Dynamics 6: 1421273. https://doi.org/10.3389/FHUMD.2024.1421273

- Colombi Ciacchi, Aurelia, María Lorena Flórez Rojas, Lottie Lane, and Tobias Nowak, eds. 2025. AI and Public Administration: The (Legal) Limits of Algorithmic Governance. Groningen: Faculty of Law / University of Groningen. https://www.julia-project.eu/resources

- Constitutional Court of Colombia. 2024. Case T-323/24. https://www.corteconstitucional.gov.co/relatoria/2024/t-323-24.htm

- Cram, Frederick. 2024. “Fairness, Relationships and Perceptions of Police Legitimacy in the Context of Integrated Offender Management”. Policing and Society 34 (4): 250-267. https://doi.org/10.1080/10439463.2023.2267733

- Danaher, John. 2016. “The Threat of Algocracy: Reality, Resistance and Accommodation”. Philosophy and Technology 29 (3): 245-268. https://doi.org/10.1007/S13347-015-0211-1

- Dávila, K.D. 2020. Please Hold. Scavenger Entertainment, United States.

- De Brito Duarte, Regina, Filipa Correia, Patrícia Arriaga, and Ana Paiva. 2023. “AI Trust: Can Explainable AI Enhance Warranted Trust?”. Human Behavior and Emerging Technologies 2023 (1): 1-12. https://doi.org/10.1155/2023/4637678

- Díaz-Rodríguez, Natalia, Javier Del Ser, Mark Coeckelbergh, Marcos López de Prado, Enrique Herrera-Viedma, and Francisco Herrera. 2023. “Connecting the Dots in Trustworthy Artificial Intelligence: From AI Principles, Ethics, and Key Requirements to Responsible AI Systems and Regulation”. Information Fusion 99: 101896. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.INFFUS.2023.101896

- European Commission. 2024. Perceived Independence of the National Justice Systems in the EU among the General Public. Brussels: European Commission. https://europa.eu/eurobarometer/surveys/detail/3193

- Felzmann, Heike, Eduard Fosch-Villaronga, Christoph Lutz, and Aurelia Tamò-Larrieux. 2020. “Towards Transparency by Design for Artificial Intelligence”. Science and Engineering Ethics 26 (6): 3333-3361. https://doi.org/10.1007/S11948-020-00276-4

- Fine, Anna, and Shawn Marsh. 2024. “Judicial Leadership Matters (yet Again): The Association between Judge and Public Trust for Artificial Intelligence in Courts”. Discover Artificial Intelligence 4 (44): 1-18. https://doi.org/10.1007/S44163-024-00142-3

- Flórez Rojas, María Lorena. 2024. “Artificial Intelligence in Judicial Decision-Making: A Comparative Analysis of Recent Rulings in Colombia and The Netherlands”. Journal of AI Law and Regulation 1 (3): 361-366. https://doi.org/10.21552/aire/2024/3/11

- Fukuyama, Francis. 1995. Trust: The Social Virtues and the Creation of Prosperity. New York: Free Press.

- Gaspar, Walter, and Yasmin Curzi de Mendonça. 2021. Artificial Intelligence in Brazil Still Lacks a Strategy. Rio de Janerio: Center for Technology and Society at FGV Law School. https://cyberbrics.info/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/EBIA-en-2.pdf

- Gelderland District Court. 2024. Case 8060619 \ CV EXPL 19-4029 ECLI:NL:RBGEL:2024:3636. https://linkeddata.overheid.nl/front/portal/document-viewer?ext-id=ECLI:NL:RBGEL:2024:3636

- Gutiérrez, Juan David. 2024a. “Critical Appraisal of Large Language Models in Judicial Decision-Making”. In Handbook on Public Policy and Artificial Intelligence, edited by Paul Regine, Emma Carmel, and Jennifer Cobbe, 323-339. London: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Gutiérrez, Juan David. 2024b. UNESCO Global Judges’ Initiative: Survey on the Use of AI Systems by Judicial Operators. Paris: UNESCO. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000389786

- Haitsma, Lucas Michael. 2023. “Regulating Algorithmic Discrimination through Adjudication: The Court of Justice of the European Union on Discrimination in Algorithmic Profiling Based on PNR Data”. Frontiers in Political Science 5: 1232601. https://doi.org/10.3389/FPOS.2023.1232601

- Hardin, Russell. 2002. Trust and Trustworthiness. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

- Hough, Mike, Jonathan Jackson, and Ben Bradford. 2013. “Legitimacy, Trust, and Compliance: An Empirical Test of Procedural Justice Theory Using the European Social Survey”. In Legitimacy and Criminal Justice: An International Exploration, edited by Justice Tankebe and Alison Liebling, 326-352. Oxford: Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/ACPROF:OSO/9780198701996.003.0017

- Jones, Karen. 2012. “Trustworthiness”. Ethics 123 (1): 61-85. https://doi.org/10.1086/667838

- Karhu, Mari, Jonna Häkkilä, and Eija Timonen. 2019. “Collaborative Media as a Platform for Community Powered Ecological Sustainability Transformations: A Case Study”. In MUM’19: Proceedings of the 18th International Conference on Mobile and Ubiquitous Multimedia, 1-5. November 26-29, Pisa, Italy. https://doi.org/10.1145/3365610.3368413

- Kinchin, Niamh. 2024. “‘Voiceless’: The Procedural Gap in Algorithmic Justice”. International Journal of Law and Information Technology 32: eaae024. https://doi.org/10.1093/IJLIT/EAAE024

- Kolkman, Daan, Floris Bex, Nitin Narayan, and Manuella van der Put. 2024. “Justitia Ex Machina: The Impact of an AI System on Legal Decision-Making and Discretionary Authority”. Big Data and Society 11 (2): online. https://doi.org/10.1177/20539517241255101

- Krause, Josua, Adam Perer, and Kenney Ng. 2016. “Interacting with Predictions: Visual Inspection of Black-Box Machine Learning Models”. In CHI’16: Proceedings of the 2016 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 5686-5697. May 7-12, San Jose, CA, United States. https://doi.org/10.1145/2858036.2858529

- Laato, Samuli, Teemu Birkstedt, Matti Mantymaki, Matti Minkkinen, and Tommi Mikkonen. 2022. “AI Governance in the System Development Life Cycle: Insights on Responsible Machine Learning Engineering”. In CAIN’22: Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on AI Engineering: Software Engineering for AI, 113-123. May 16-24, Pittsburgh, United States. https://doi.org/10.1145/3522664.3528598

- Marabelli, Marco, Sue Newell, and Valerie Handunge. 2021. “The Lifecycle of Algorithmic Decision-Making Systems: Organizational Choices and Ethical Challenges”. The Journal of Strategic Information Systems 30 (3): 101683. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JSIS.2021.101683

- Mayer, Roger C., James H. Davis, and F. David Schoorman. 1995. “An Integrative Model of Organizational Trust”. The Academy of Management Review 20 (3): 709-734. https://doi.org/10.2307/258792

- Medvedeva, Masha, and Pauline McBride. 2023. “Legal Judgment Prediction: If You Are Going to Do It, Do It Right”. In Proceedings of the Natural Legal Language Processing Workshop 2023, 73-84. Singapore: Association for Computational Linguistics. https://doi.org/10.18653/V1/2023.NLLP-1.9

- Meyer-Resende, Michael, and Marlene Straub. 2022. “The Rule of Law versus the Rule of the Algorithm”. Verfassungsblog, March 28. https://verfassungsblog.de/rule-of-the-algorithm/

- Murrer, Adina. 2023. “Hesse and Brandenburg Cooperate on the AI Project ‘FraUKe’”. Hessen Ministry of Justice, November 13. https://hessen.de/presse/pressearchiv/hessen-und-brandenburg-kooperieren-beim-ki-projekt-frauke

- NSW Government. 2024. “Bail and Accommodation Support Service”. Youth Justice NSW. https://www.nsw.gov.au/legal-and-justice/youth-justice/bail-and-accommodation-support-service