Introduction

This article presents an experimental ethnography of the experience of Tikuna, Uitoto, Cocama, Bora, and Inga indigenous peoples of the township of Tarapacá, Amazonas, Colombia playing the “Juego de Chagras”1 or the chagras game, as part of a participatory research project on agrobiodiversity-related knowledge. One of the objectives of this project was to increase indigenous peoples’ dietary autonomy and promote their traditional knowledge on biodiversity in the Department of Amazonas, in the Colombian Amazon. In 2012, indigenous organizations of the township of Tarapacá and the Sinchi Amazonian Institute of Scientific Research agreed to support the members of these indigenous groups by helping to develop a local market in which they could sell their traditional products. As a result of workshops on social cartography (Sinchi Institute 2014, 34), daily records of food consumption (De La Cruz et al. 2016, 42), and interviews with traditional farmers, we observed that these indigenous peoples sold their products at prices which were unfavorable to them but quite profitable for intermediaries (De La Cruz and Acosta 2015, 10). This situation disincentivized the continuity of traditional practices associated with cultivating and processing autochthonous crops (De La Cruz 2015, 29; Eloy and Le Tourneau 2009, 218; Eloy 2008, 17; Fontaine 2002, 177; Peña-Venegas et. al. 2009, 84; Yagüe 2013, 31).

The idea of carrying out an experimental ethnography using a board game as part of participatory research was a response to criticism by the indigenous peoples of Tarapacá that research results often do not have a significant positive impact on their territories. They commented that “scientific” methodologies typically do little to resolve the problems that they identify, and that research results remain limited to the production of academic documents. This is partly due to the fact that methodologies used in encounters between indigenous peoples and civil servants are generally meetings in which “people just speak” and in which non-verbal communication is rarely explored. Participatory research may be understood as a series of approaches and methods that propitiate analysis, mutual learning, and knowledge-building regarding a collective situation (Shanley and López 2009, 538) . Board games make “experimental ethnography” possible by integrating ethnography and field experiments. In this study, experimental ethnography was conducted by intentionally introducing a stimulus during fieldwork, in this case, a board game with rules and procedures (Castañeda 2006, 86) represented by an aesthetic2 model, in which subjects make decisions in a controlled situation (Poteete, Janssen, and Ostrom 2012, 86). Experimental ethnography through board games makes it possible to document fieldwork based on game results, participant observation, and dialogue among participants (Ingold 2017, 5).

The chagras game simulates local production and sales of agricultural products. This thematic game represents some of the decisions that have to be made by Amazonian indigenous peoples concerning planting, harvesting, processing, bartering, and the sale of the products grown in their chagras. The researchers began with the hypothesis that the main reason that indigenous peoples sell few products from their chagras was that in Tarapacá there is no local marketplace. Rather, they generally sell on the street or to intermediaries at very low prices. With the board game, new variables of analysis emerged, such as intra-community redistribution, sufficiency, and seasonality of planting and harvesting, which transformed the initial hypothesis and explained the low level of sales of chagra products by indigenous peoples and the lack of a permanent marketplace. Thus, the game brought to light categories of analysis that explain how chagra management, and local sales and barter are conducted in Tarapacá.

Implementing the chagras game exposed the pertinence of games in both experimental and participatory research methods. Players make decisions based on meaningful contexts that arise from their personal experience of playing the game. The term “meaningful context” refers to the subjective motives of an action; the motive is the meaningful context that the actor or observer considers to be the appropriate basis for a form of behavior (Weber 2002 [1922], 49). According to the Geertz’ (2003, 92) perspective interpretive anthropology, cultural patterns give meaning —that is, objective conceptual form—to social and psychological realities by shaping themselves to these realities and vice versa. Thus, actors’ motivations and the ends to which these motives should lead are “provided meaning.” Meaningful contexts are the texts underlying peoples’ decisions, which, in turn, give meaning to cultural performances (Alexander 2009, 33) that are manifested in the actors’ thoughts and justifications and how these emerge in the game sessions. Experimental ethnography results from the meaningful contexts that reveal cultural performances when players express their thoughts through folk sayings, narratives, or metaphors that blur or elucidate the limits between “reality” and the simulation.

The first section of this article presents some precedents concerning the use of games as a method of experimental ethnography for participatory research. We then theorize on games as tools that catalyze cultural performances and analyze these performances based on the meanings that people give to their decisions and to those of others. Following this, we present an experimental ethnography which analyses the actors’ actions and decisions during the game and how these actions are connected to the decisions they make on a daily basis in their environment; we show how the players’ contributions and criticisms led to modifications being made to the game, as they pointed out scenarios that the game’s creators did not contemplate. Finally, we discuss the principal contributions of the chagras game to the issue of the sale of local products in Tarapacá and conclude that the most significant contribution of board games to participatory research is to produce meaningful connections among the topic, the mechanics of the game, the players’ interpretations, and their daily decisions.

Experimental Ethnographic Approach to Using Strategic Board Games for Participatory Research

In the past 20 years, academics and scientists have increasingly used board games in applied and participatory research. Despite the recent popularity of employing board games as sources of “data” for social models (Edmonds and Meyers 2013, 9), few ethnographers have used anthropological frameworks to theorize about the application of the games themselves. Few studies have analyzed the relevance of games as a tool in the experimental field, or the significance of decisions which emerge as a result of the interaction between the experiment and the players’ social reality.

In the literature, the term experimental ethnography is used in a variety of disciplinary fields. The principal difference among disciplines is in their understanding of “experimental.” In the 1970s, cognitive anthropology jointly studied mental processes and cultural contexts (Boster 2011, 133). This branch of anthropology maintains a distance between subject and object, as do the positivist sciences, and it combines qualitative methods (stories) with quantitative methods (numbers). Sherman and Strang (2004, 213) refer to experimental ethnography as a strategy to create experiments that create an effective “black box”3 test of cause and effect and an understanding of how those effects occur inside the black box, “person by person, case by case, and story by story.” For other disciplinary perspectives, such as the anthropology of theatre and feminist studies, experimental ethnography involves embedded, embodied, sensorial, empathetic learning — through sensorial means such as games— that transcends a simple combination of participation and observation (Magnat 2016, 219). Research through games makes it possible to catalyze stories, narratives, empathy, and simulation. Games are performative (Flanagan 2009, 48); that is, playing is a cultural phenomenon that transcends the confines of purely physical or biological activity. According to Huizinga (1980 [1944], 45):

In play there is something “at play” which transcends the immediate needs of life and imparts meaning to the action […]. Play is a voluntary activity or occupation executed within certain fixed limits of time and place, according to rules freely accepted but absolutely binding, having its aim in itself and accompanied by a feeling of tension, joy and the awareness that it is “different” from “ordinary life.”

For the researchers of the present study, the key to conducting experimental ethnographies using board games is the ability of such games to represent the actors’ decisions and catalyze cultural performances which reveal the players’ meaningful contexts. An ethnography communicates an experience which occurs during fieldwork, presenting the lessons learned through research in legible terms. Experimental ethnography involves the systematic presentation of stimuli during fieldwork in order to provide a strategic trigger consisting of multiple tactical procedures, ranging from “passive” observation to directly provoking the subjects. Methodologically, experimental ethnographies recognize that data both exists prior to the study and it emerges through interactions occurring during the research process (Castañeda 2006, 82).

Experimental ethnographies combine a variety of techniques and methods in a space-time context in order to trigger methods of producing relevant information (Castañeda 2006, 82); they embed the subjects (e.g., players, as well as game creators and testers) in performances in which they must make choices according to the paths they wish to follow and the specific set of meanings they wish to project. These choices are the scripts that either precede the performance and are (more or less) revealed by them, or that take form beforehand and are textually reconstructed post-hoc (Alexander 2009, 29). A game makes it possible to construct analyses based on the meanings that the players give to their own performances as well as to those of others. The purpose of the game is to generate subjective meaning in players which allows for convincing performances (Alexander 2009, 36), and to alter the value of what is at stake (McKee 1997, 62). To reach this point, the structure of the game should bring together and simplify the scripts upon which the plot is constructed. The players should reach crossroads at which they must make decisions based on values that they may express as moral binaries (e.g., I like this or don’t like it; I’ll plant or not plant). If the performance is energetically and skillfully manifested in moral binaries through metaphors which catalyze psychological identification, the players’ understanding of daily life can be applied to the particular situation being represented using drama (Alexander 2009, 37).

Board Games for Applied and/or Participatory Research

Games may be classified in many ways; for example, according to their level of abstraction vs. realism, or according to the level of information that the players are provided with based on which to make decisions. Games may also be classified as “strategic” vs. random, though they may involve a combination of both of these. The more strategic the game, the greater the possibility of the result being determined by the players’ decisions. In strategic board games, players make decisions with relative autonomy; that is, strategic games simulate conditions in which the players have full or almost full knowledge of the possibilities of the game. All players start with the same initial conditions based on which to reach the ultimate goal. These games are called board games because they are played on a sort of firm topographic map that defines the relationships among the game’s components and its space. The positions on the map may be determined according to discrete or continual values (Nielsen et al. 2014). Game designers may even attribute an artistic aspect to board games, linking the experience of the game with its aesthetic elements (Flanagan 2009, 9).

Games with research purposes are designed according to a previously identified situation. The iconography and the mechanics of the game should represent the context and the system of logic that the researchers wish to recreate. In order to function, they should at least partially represent reality as the participants perceive it. The game should address a situation that requires collective action and, therefore, interaction among participants. The actions selected by the players will impact the development of the game, which is not entirely defined from the start (Peñarrieta and Faysse 2006, 11).

Different researchers have described how games applied to research serve to 1) gather information on the local reality and its actors; 2) carry out analysis, including making conceptual and instrumental inferences which help to understand the phenomena studied; and 3) design possible strategies of intervention (Camargo et al. 2007, 477). Games implemented in applied and/or participatory research focus on decision making and collective action (Speelman 2014, 20; Janssen and Anderies 2011, 190; Cardenas, Maya, and Lopez 2003, 63; Luis García-Barrios et al. 2011, 364; Camargo, Roberto Jacobi, and Ducrot 2007, 472). The literature describes games which address problems in such disciplinary fields as microeconomy, education (Victoria and Utrilla 2014, 15-26), natural resource management (Castella 2009, 1315), shared resource use (Cárdenas 2009, 1313), urban studies (King and Cazessus 2014, 272), conflict resolution, resilience, and adaptive capacity (Speelman 2014, 44). They have been developed and used for a variety of objectives, including gathering data on models of socioecological systems on a variety of scales (Peppler, Danish, and Phelps 2013, 687); awareness raising and educating regarding complex systems (García-Barrios, Perfecto, and Vandermeer 2016, 192; García-Barrios et al. 2017, 37); testing hypotheses, especially with respect to managing common resources (Janssen and Anderies 2011, 191), and cooperation and coordination with respect to rural land use (García-Barrios, García-Barrios, Waterman and Cruz-Morales 2011, 365; García-Barrios et al. 2015, 13). These studies to some extent describe using games as an innovative applied, experimental, participatory method (Cardenas, Maya, and Lopez 2003, 64) of facilitating learning while generating predictive models of future behavior with respect to a given phenomenon (Speelman 2014, 22).

The Chagras Game

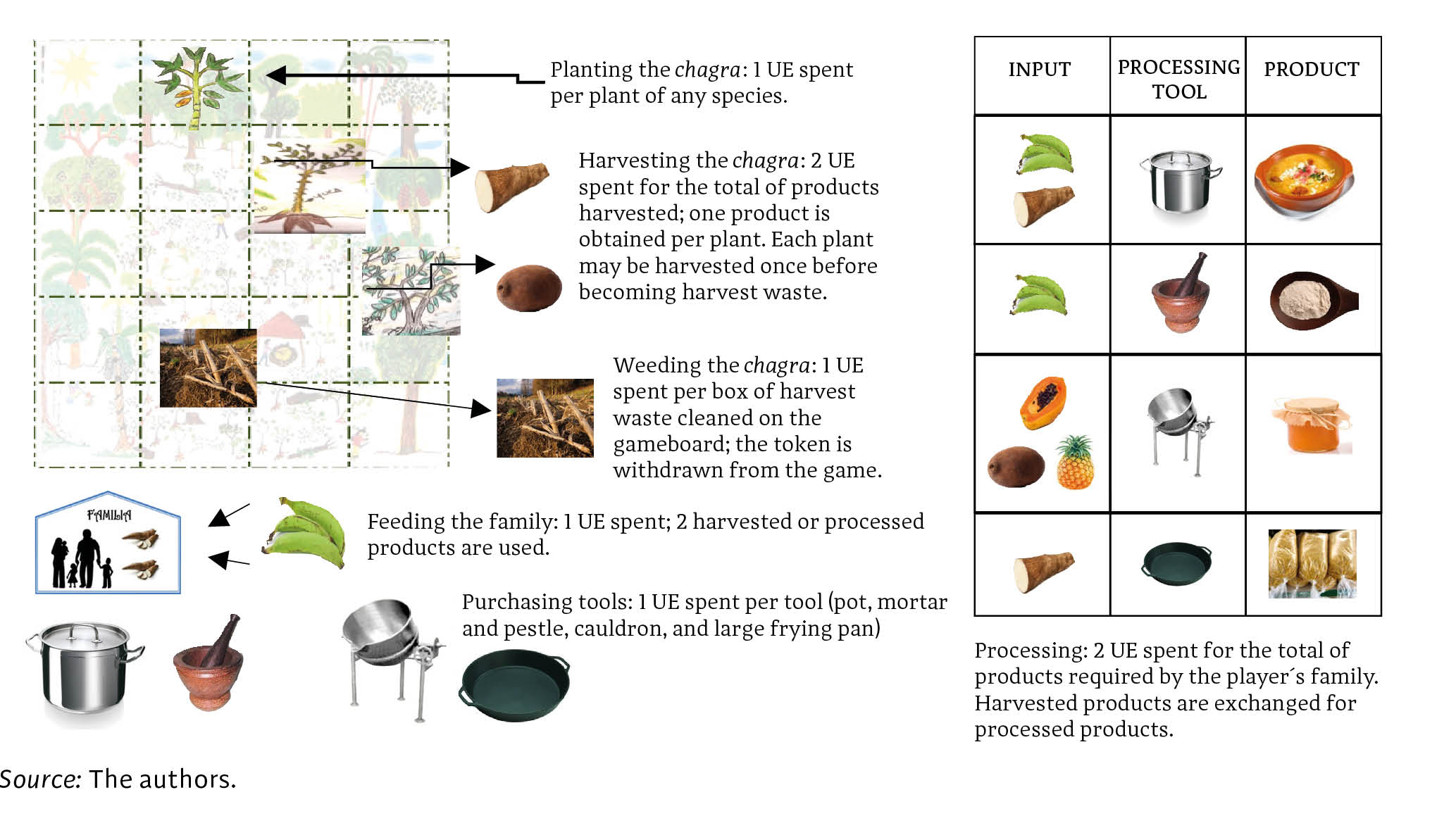

The chagras game was designed to be implemented as part of a participatory study of chagra fairs in the urban center of Tarapacá as a local sales option for chagra farmers. Thus, it explores the relationship between cultivating chagras and local commerce. The objective of the game is to produce food for the family, food for sale, and to process some of the harvest for sale. The game consists of five cycles. In order to remain alive, players should feed their family at least once per cycle. Each player is provided with a game board representing his or her chagra and three Units of Effort (UE) to spend during his or her turn to carry out the actions shown in Diagram 1.

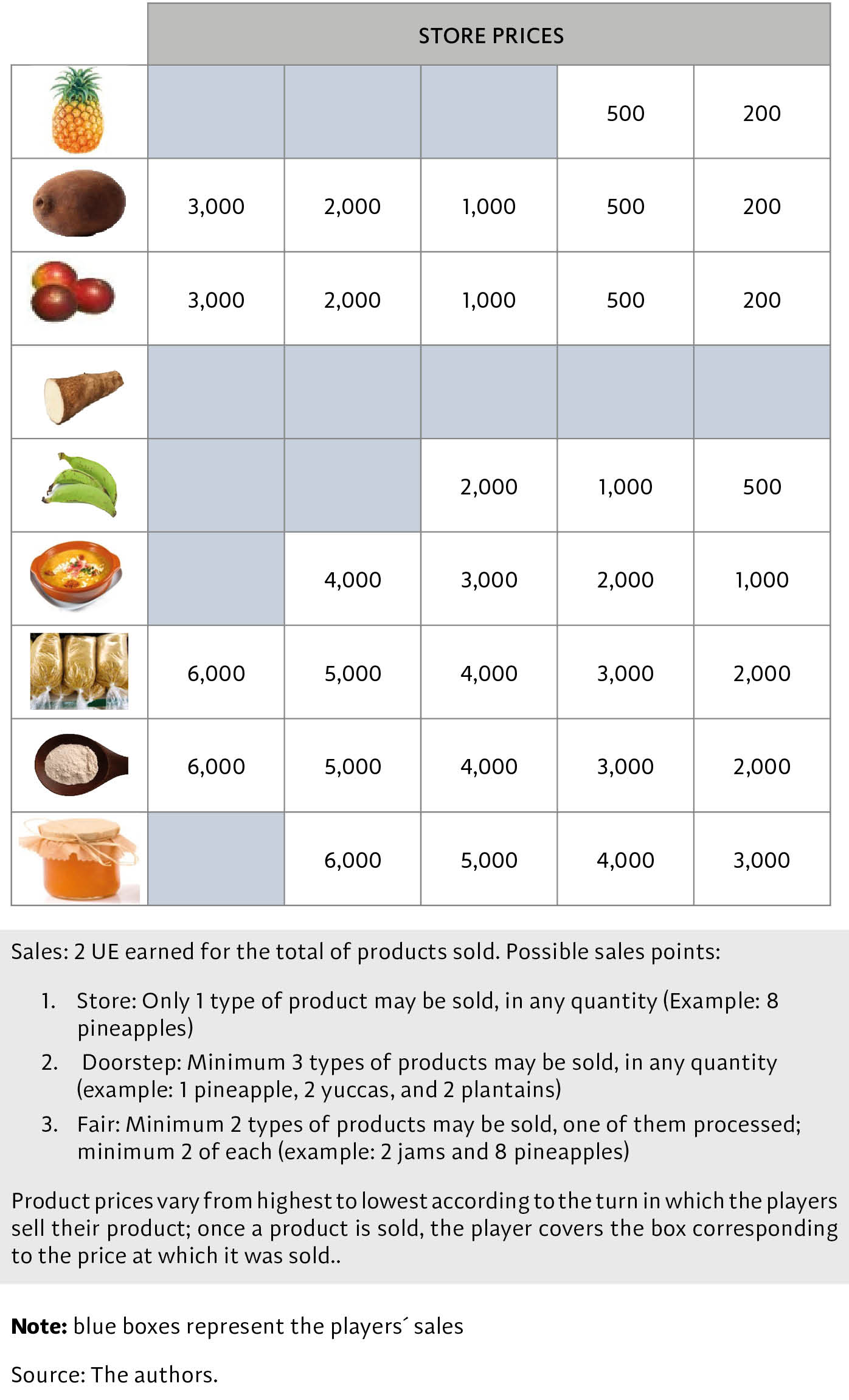

The actions of cultivating and food processing are conducted on each player’s game board, and those relating to sales are conducted individually on a single collective game board, where purchase-sale prices are modified as the products are offered by each player in the various sales points. The three possible sales points - store, doorstep, and fair - have different stipulations with respect to type of product and quantity which may be sold, as shown in Diagram 2. Producers’ sale prices are lowest in stores, mid-range on the doorstep, and highest at the fair. Players may exchange or sell their products with each other only when it is their turn. They can do this only once and without spending UE. While harvested food that is not sold or consumed before the end of the cycle is lost, processed products and unharvested crops are not. After harvesting, the chagra remains full of weeds, and before re-planting it must be weeded. At the end of the game, players obtain points for: (1) diversity of species planted (1 point per species), (2) processing tools owned (5 points per tool), (3) selling in stores (2 points), (4) selling on doorsteps (5 points), and (5) selling at fairs (10 points).

Study Area

The township of Tarapacá lies on the border of Colombia, Peru, and Brazil in the north-eastern Amazon, on the on the Cotuhé River estuary along the Putumayo River. The northeast region of the Amazon is covered by tropical forest, and is crossed by the Caquetá, Putumayo, and Amazonas Rivers. Tarapacá has 3775 inhabitants, 51.3% of whom live in the main urban center, and 48.7% of whom live in 9 rural communities on the Cotuhé and Putumayo Rivers. Eighty-nine percent of the population —or approximately 2200 inhabitants— belong to one of 10 indigenous groups: Tikuna, Uitoto, Bora, Cocama, Yagua, Macu, Inga, Okaina, Nonuya, and Andoque (ASOAINTAM and CODEBA 2007, 7). Tarapacá contains two resguardos:4 Uitiboc (95,000 ha) and Cotuhé Putumayo (250,000 ha). The principal economic activities are hunting, fishing, and slash and burn agriculture, known locally as the chagra system. Closeness to commodity markets has favored the introduction of non-traditional economic activities such as gold mining, and commercial fishing. Over time, the local diet based on chagra products, hunting, fishing, and gathering has been combined with purchased processed foods (Acosta et. al. 2011, 15; Peña-Venegas et. al. 2009, 29; Yagüe 2013, 30).

Indigenous families in Tarapacá clear fields of two hectares or less to plant chagras with up to 28 food species, including yucca (up to 21 varieties), plantains, pineapple, and peppers, as well as coca (Sinchi 2014, 18). Chagras are generally cultivated according to the minga system, by which families jointly plant each other’s fields on a rotational basis. An average of 34% of the families’ food is a result of self-provisioning, principally from agriculture, fishing, and hunting; of this, 26% of the species come from chagras and homegardens, and 85% of families sell some of the foods harvested on their chagra. Sixty-three percent of local foods, including manioc flour, fish, cassava, and wild game, are acquired through purchase, of which 60% is bought in local stores owned by non-indigenous merchants (De La Cruz et al. 2016, 48).

In Tarapacá, families exchange labor for agricultural products via the mingas system, and they also cultivate products for sale, although in general, only a small quantity of local products are distributed through stores. The majority of food crops, in particular yucca and plantains, are obtained directly from chagras or homegardens or through exchanges with other families. Families rarely purchase food in stores, although some farmers sell their products to store owners or directly to consumers. Fish, foul, pigs, cattle, and wild game are purchased mainly from merchants who own cold storage facilities, or directly from hunters and fishers. The demand for animal protein is quite high and not all peasant families are self-sufficient in terms of these products (De La Cruz Nassar 2015, 104).

Study Group

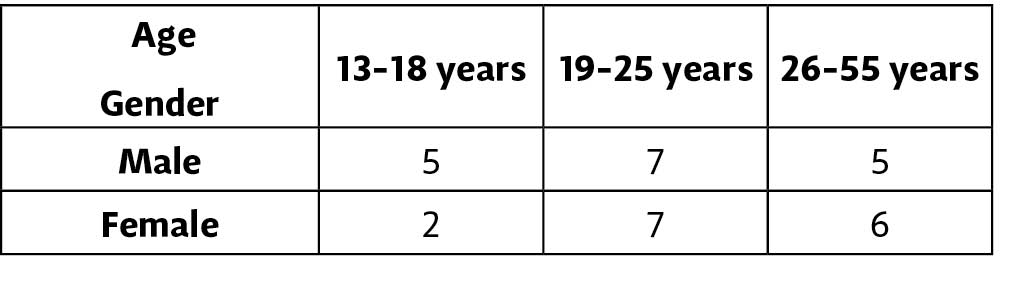

The game was played by 32 indigenous people of the Uitiboc Resguardo, aged 13 to 55, of whom 19 were male and 13, female (see Table 1):

Ten sessions were played, each of them including two to four people. In two cases, the game was played in teams, and the others were played individually. Some sessions were played by only youth or women, and others were mixed in terms of age and gender. The following information was recorded: (1) number of points obtained by each player; (2) participant observation during the session; and (3) players’ comments during and after the session. Participant observation conducted by the first author in Tarapacá in 2009 was also considered.

Experimental Ethnography Using the Chagras Game

Playing a board game as a way of participating in research was completely new for the indigenous players in Tarapacá. Board games in general are very uncommon among them, and many initially, associated the chagras game with gambling, while a few associated it with the concept of strategy - particularly those familiar with chess. Introducing a board game as part of fieldwork in a research project was unexpected but happily accepted and taken seriously by participants. As they played the game and noticed the iconography of the gameboard and tokens, they were particularly curious to see themselves represented in a “real” game.

The results of each game were analyzed in conversations between the lead researcher and players following the game sessions. Players were observed to base their decisions on two different sets of criteria: (1) their actions in real life and (2) a strategy to win the game which differed from their real-life actions. Players made decisions during the game by combining both types of strategies. A number of variables relating to chagra management became evident through conversations during and after the game sessions. These included work exchanges through mingas; seasonality of planting, harvesting, and weeding; and the way in which these variables influence the local sale and bartering of products. Once the results of all game sessions had been analyzed, they were presented in a meeting with some indigenous leaders.

Cultural Performance: Traditionalists vs. Business People

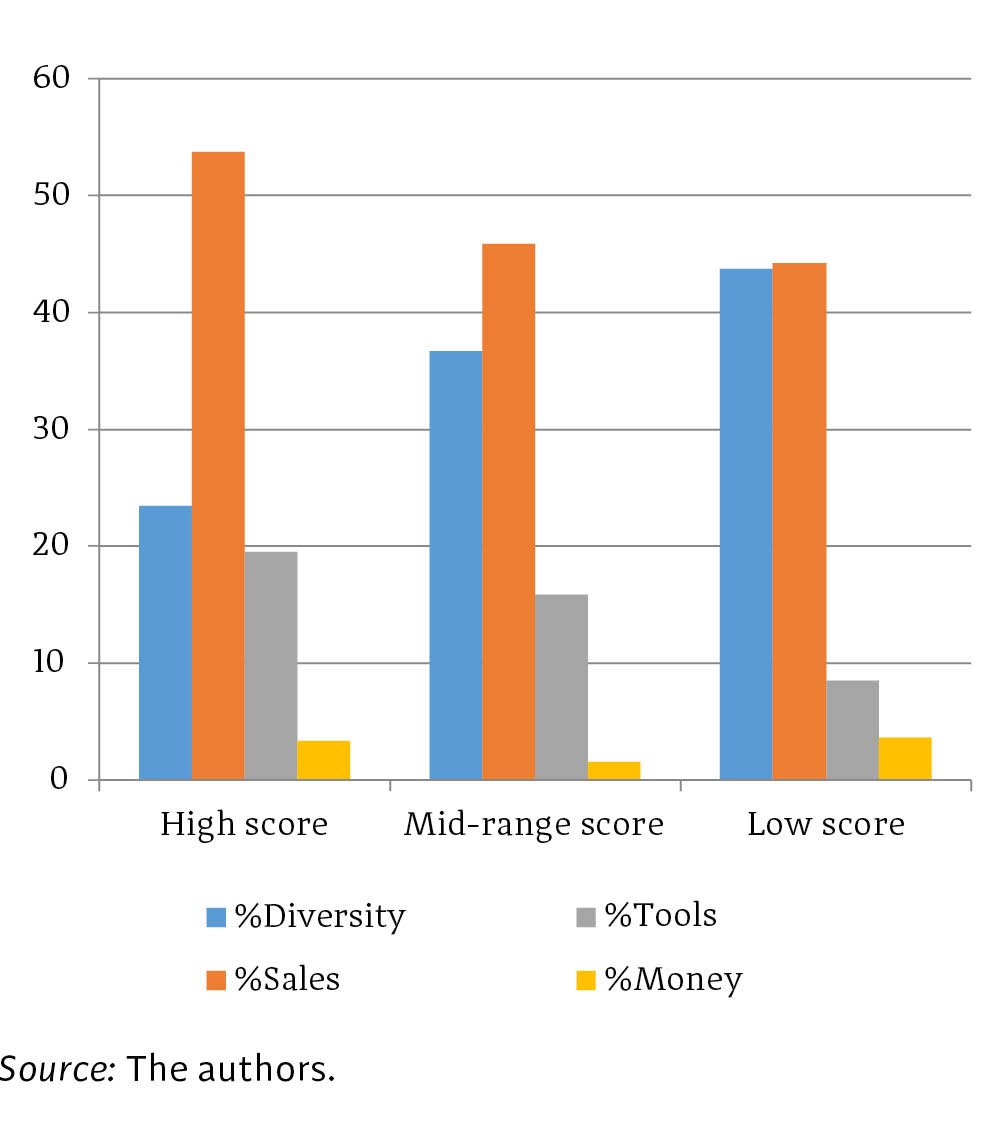

The chagras game allowed participants to compare and contrast different types of game strategies, which were then reflected in their scores. According to Figure 1, those who obtained a high score invested a large percentage of their earnings in tools for processing harvested crops. The higher sale price of processed products allowed them to reinvest in more tools, but these players also tended to dismiss the value of diversity in their chagras. Those who obtained moderate scores based their strategy on selling unprocessed products at all three sales points. These players maintained a low to moderate level of diversity in their chagras. Those with the lowest scores maintained a more diverse chagra and designated only some of their products for sale.

Figure 1.

Average percentage for species diversity, product sales, tools, and money according to the scores obtained during the chagras game

Upon commenting on their own strategies and those of others, players contrasted those who played with the intention of earning a high score with those who obtained lower scores. The former called themselves the “business people”; they sold harvested products to purchase tools to process some of their harvest, which they also sold. The others called themselves the “traditionalists,” and sold less but had greater diversity. The players’ comments allowed for a better understanding of local dynamics of seasonality of planting, harvesting, and weeding, as well as local commerce.

Chagra Management and Sales

In the game, any player could harvest his or her entire chagra by spending 2 UE; thus, the energetic cost was the same regardless of the quantity harvested. Similarly, all players could sell some or all of their harvest by spending 2 UE. Nonetheless, some players —the traditionalists in particular— did not harvest their entire chagra; rather, they left some plants of up to three different species (of the five permitted in the game) unharvested. Similarly, some decided not to sell all their harvested produce.

The first author —as game moderator— initially thought that he failed to make it clear that each player could harvest everything in one turn and sell it all in another. As the game advanced, the moderator often reiterated this possibility, but the actions of many players suggested that they felt that they should not harvest nor sell everything in a single turn. If the game did not place any limit in UE on harvesting their entire crop, what was establishing that limit?

During one game session, each time that Joaquín Hernández, a fisherman, hunter, and chagra farmer of the Uitoto ethnicity conducted an action, he explained out loud how he made his decision. Joaquín’s words cast light on the how he considered that the chagra should be managed:

Joaquín: I’ll harvest the plantains.

Pablo: What else do you want to harvest?

J: Well, it’s time to harvest the plantains and the pineapple. I’ll harvest both…

P: O. K. Anything else you want to harvest?

J: No, just that, because the yucca was planted recently (…) and with that, I’ll feed my family.

A brief analysis of this dialogue elucidates two variables of chagra management: the seasonality of planting and harvesting different species, and the idea of sufficiency. For indigenous people of the Amazon, it is unrealistic to think that all species can be planted and harvested at any time of year, and this is reflected in their decisions during the game. Joaquín says, “I’m going to plant yucca because the plantains are already being harvested.” In another move he states: “[…] it’s time for me to plant [yucca] again, because I already planted the first round […] The plantains are already being harvested […] I’m going to plant yucca again.” Thus, chagra management depends more on the seasonality of planting and harvesting and the farmer’s concept of sufficiency than on their ability to maximize yield.

During harvest time, families do not harvest everything from their chagra. Rather, they harvest some of each crop, generally that which is most necessary. As they do not have pack animals or roads, they must carry their harvest on their backs. Furthermore, many products are consumed in the chagra by the family and animals, and some people jokingly say that they have to make sure they leave some for the thieves. With respect to why some players prefer to sell only part of their harvest in a given turn, much of the products from the chagra are redistributed among the families that helped to prepare the land and plant the chagra. As products such as yucca and plantains are in a greater demand, they tend to sell some of these crops.

Sufficiency is the other variable implicit in Joaquín’s dialogue. Chagras are planted in mingas, which are economic, social, and cultural exchanges. Therefore, much the products of the chagra are planted for families that participate in the mingas to consume. A family must generously give to others, lest others think that their retribution is insufficient. Thus, sufficiency transcends the satisfaction of dietary needs. As the elder Teófilo Seita states, it has to do with abundance, which is a regulating principle of social relations.

When there’s abundance, there’s no envy. I’m not fighting because the other person didn’t give me yucca, didn’t give me plantain, didn’t give me pineapple, didn’t give me the manioc flour that he made… I’m not angry with him, nor am I saying bad things about him. Why? Because I have [all that] too. I’m not going to rob another. That’s unity, abundance, respect.

In order for chagras to satisfy families’ food needs in quantity and quality, they should be cultivated according to traditional knowledge. Families plant and harvest chagras according to the local agricultural calendar following cultural principles related to sufficient production. Sufficiency is measured not only in terms of the quantity produced; it is also a principle involving social relations based on exchanges such as those of the mingas. Sufficiency is strictly associated with the principle of abundance, by which indigenous families re-establish the equilibrium altered by breaking ground to plant the chagra by giving back to the forest through planting fruit trees, which provide shelter as well as food for the animals that live there. Fulfilling this principle guarantees the possibility of having a productive chagra and a good diet (Acosta 2013, 9). The principle of abundance differs from that of scarcity, in that the insufficiency of material resources is the starting point of all economic activity; production and distribution are determined by price behavior, and all livelihoods depend on earning a monetary income and spending it (Sahlins 1983, 39). The principle of scarcity assumes that rational individuals, such as consumers and producers, wish to obtain maximum utility and profits (von Neumann and Morgenstern 1969, 23).

For Nílida Mendoza, who identified herself as a traditionalist, it was more important to follow a subsistence strategy based on diversity of species in the chagra than prioritize the sale of products:

When one is “playing at” the chagra, whether in real life or in a game, I told you we can’t be lacking for food and we can’t be lacking the products that we have in the chagra. Watching the business people - those who had more in the end… they wanted to buy; they didn’t have products in their chagras anymore; they had to look in the other chagras, but sometimes the other chagras didn’t have products and they didn’t have anything to harvest, so they went about buying and buying. Our situation contrasted with theirs in that we had enough to feed our families. [We had] the products we needed in the chagra; we had everything, we even had enough to sell. We don’t go to a [store in town to buy things], we had everything… family sustenance.

The position of Nílida as compared to that of the business people with respect to chagra management reveals a different game strategy related to the fulfilment of a basic requirement for the game to continue: feeding the family once per cycle. Anyone who does not comply with this rule loses everything: the chagra, the harvest, money, and tools. While this never occurred, a tendency was observed that is not visible upon analyzing the scores: men tended to feed the family at the end of the cycle and women at the beginning. Thus, the women prioritized feeding the family more than the men did. This coincides with the fact that in present-day Amazonian indigenous societies, women are principally responsible for planting, cooking, and serving food.

Other players emphasized that families persist in cultivating the chagra not only to be able to maintain their traditional diet, but also to obtain income to satisfy other needs met by purchased products. Unlike that of Nílida, Berlandy Gabino’s strategy included processing harvested products and reducing diversity in the chagra. According to him, this makes it possible to provision the family and to sell some products to obtain an income to “acquire soap, rice, sugar… We buy what we need. Even the chagra has its clientele; the chagra is also for them.” This reveals how indigenous people of the Amazon have been adapting chagra management to their current needs based on their growing relationship with the market economy.

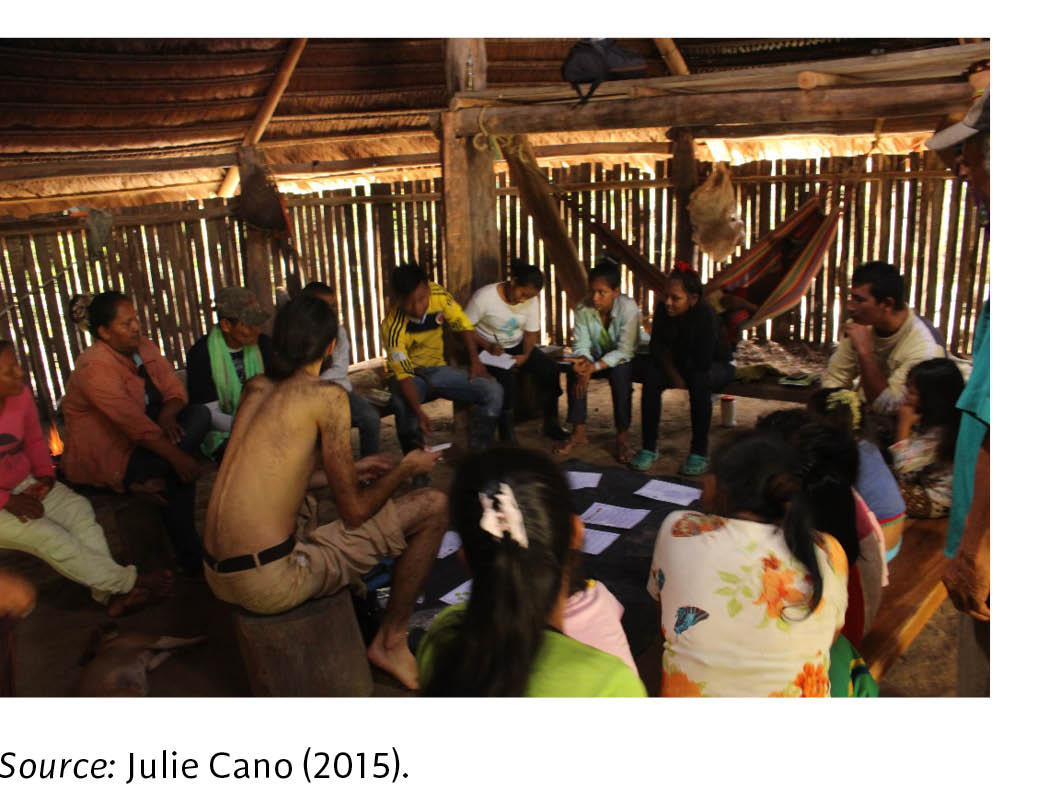

Image 1.

Members of the Cocama indigenous group at the Cardozo Community Center during a session of the chagras game. Tarapacá, Amazonas, Colombia, 2015

According to one of the business people, Israel Falcón, the game allows players to compare managing a chagra as a “microbusiness” is managed with their observation of real-life chagra management. Israel points out that although his strategy in the game was to sell his products and reinvest the profits, real-life chagra management cannot be solely based on profits.

For a small business to be successful, you have to invest what you earn. If a chagra neither provides profitability nor what [you] want to produce, then the profits are invested. That’s what we did - buy [processing tools] to later sell [processed products]. The game is very strategic, and that’s how real life is; [you] have to sell to have something to consume. This was invented as a game. If you think about real life, it’s different. If we hadn’t sold everything, we would have still had something in the chagra, and in real life you can’t sell the entire harvest; if you do, then, there aren’t products left for exchange.

Regardless of the result of the game, some players’ comments pointed to the conditions needed to sell a product in Tarapacá. For example, for Miguel Palma, a lack of profits from chagra products is due to the distance of his community from the urban center.

If you take a bunch of plantains from here [the community] to somewhere where you can sell it, and ask for a particular price, people will find it expensive and try to lower that price. You carry a bunch from here to the town and they don’t pay what you ask… you’re giving away the product. So, how do we get our work to be valued? Because in the stores, product prices go up every day, but [the price of] a bunch of plantains goes down instead of going up, and the manioc flour gets to the stores and they take it for just 3,000 or 3,500 [pesos]5, it’s not worth it for us.

Weeding the Chagra

On the game board, each player may plant up to 12 species simultaneously. When the player harvests a crop, the space where it was planted remains full of weeds, so the players have to weed before being able to plant again. Players with low and mid-range scores, despite having more than half of the available space on the gameboard to plant, preferred to weed the spaces that were full of weeds instead of using their actions to plant, harvest, and/or sell their products.

This could be explained by the way in which the families manage the chagra. After the game sessions, the players spoke of the importance of preparing the chagra and the other tasks they carry out in the chagra. If they don’t look after the chagra, the weeds grow and the crops may die. A chagra is considered to be appealing to the eye when it is diverse and weeded, with paths of sand surrounded by pineapple plants, coconut trees, yucca, plantains, and papaya trees. When people go to work in the chagra, they carry machetes almost everywhere they go and use them to cut fallen branches, trees, and weeds, to harvest fruit, and in general to transform the forest into chagra. In the chagra, people almost unconsciously cut weeds and hill crops or fix a path as they converse. Weeding keeps away worms, moths, and animals that eat the fruits, and allows sunlight to reach the crops so that the can plants grow.

Maintaining a chagra diverse and weeded —as traditionalists insisted on maintaining their chagra— guarantees that it will continue to produce. A weeded chagra is an indicator of good health, and its significance transcends the physical condition of the space. As Fausto explains, “If the chagra is weeded, it means that you too are healthy, but if the chagra is unkempt and full of weeds, someone in your family is sick.”

Discussion

Critique and Modifications to the Chagras Game

The game sessions produce performances that lead the participants to compare their daily life situations with the simplified model presented by the game. The game represented everyday decisions that indigenous peasants of the Amazon make and that are immersed in broader cultural, social, and economic contexts. This exercise of simplifying and isolating certain variables was interpreted by the players in different ways. For example, for one group of students, the chagras game dealt with “selling the products of the chagra.” Others said that it dealt with “planting the chagra,” and a few others mentioned that it dealt with “being strategic.” For the first group, the intention of the game was entirely commercial, and for the second set of players it represented caring for the chagra. For the study, the initial objective of the game was to relate both aspects, but few players interpreted it in this manner.

Some players criticized the way in which the game was calibrated to represent the sale prices at each of the sales points. One group of students considered the sale prices to be the same at all sales points, which contrasts with the prices found in our field observations. This suggests the need to increase and further specify the criteria that determine the prices of chagra products in Tarapacá. If prices do not vary among sales points, then other factors which determine the prices of chagra products should be taken into consideration, such as the existence of face-to-face relations, family participation in mingas, or sales among neighbors. These factors were not contemplated in the game, and led the study to consider the relative advantages and disadvantages of peasants selling their harvest to intermediaries. This demonstrates the need for the game to represent relationships of exchange such as the mingas, and take into account non-monetary benefits when players sell directly on their doorstep or in fairs.

Other players’ suggestions addressed the need to take into account cooperative actions. For example, some women who are part of the Tarapacá Community Women’s Association (ASMUCOTAR), whose members jointly sell their products at fairs, manifested that selling at a fair was not an individual decision, but rather that it depended on whether the majority of members of the association agreed. This suggested the need to modify some of the game’s rules and objectives. The point system was also questioned. Despite the fact that board games are organized around an objective, players’ discussions of the chagras game showed that the objective should not be geared towards winning or losing, thereby classifying the players in terms of success or failure. This does not imply a need to abandon the idea of an objective or a point system - much less a challenge, which is the exciting part of the game. Rather, the game should provide players with a variety of alternatives for playing and refrain from classifying them as good or bad players.

Chagra Management and Local Commerce of Agricultural Products: Meaningful Contexts

The validity of a game as an experimental method is determined by the congruence of its results with field observations. The chagras game resulted in meaningful interactions which help to understand the dynamics of sale and barter of agricultural products in Tarapacá. It demonstrated how the local commerce of these products is determined by the cycle of planting, harvesting, and weeding the chagra 6. Despite the fact that the game allows for a great amount of liberty in the timing of planting and harvesting and quantity of plants planted, players simulated the real-life seasonality and quantities of chagra species planted. This reflects the fact that the decentralized way in which local commerce of agricultural products takes place is largely influenced by the seasonality of planting and harvesting, the quantity planted, and the fact that the products are principally cultivated to be consumed by the family and others who help in the mingas. These results are significant as only a small portion of chagra products are destined for local commerce, and they highlight the economic disadvantage of cultivating principally for sale. Nevertheless, those who played the game using a sales-oriented strategy stated that their families are interested in obtaining income from agricultural products and having set spaces to sell their products.

The results of the game also coincide with the fact that not all chagra products are for sale, and that when a grower destines the majority for sale, crop diversity tends to diminish. This coincides with findings by some authors who compare agricultural diversity in human settlements of the South American Amazon with those of varying levels of urbanization (Arcila 2011, 50), showing a reduction in agricultural diversity in settlements closest to urban centers. In general, indigenous people of the southern part of the Colombian Amazonia have reduced the amount of autochthonous species which are significant to the traditional diet that they plant; these have largely been displaced by purchased products, as well as by greater dependence on gainful activities in order to obtain income to acquire such products (Acosta et. al. 2011, 30).

Reviewing players’ game strategies and comments led us to modify the initial hypothesis that due to the lack of a set market, local peasants sell few of their chagra products. The new hypothesis took into account the ecological particularities of the chagra system and the social relations within which food is produced. Local sales of chagra products are not as significant as their redistribution through mingas due to the different species’ varying planting and harvesting cycles and the difficulties involved in taking their products to town. Nevertheless, this is rapidly changing due to indigenous families’ increasing involvement in the formal market economy based on natural resource extraction.

Pertinence of Board Games for Participatory Research

Fieldwork demonstrated the relevance of the game to some members of the indigenous population, its pertinence as an experimental field method, and the meaningful connections underlying the experiment and the players’ social reality. The researchers neither assumed that the categories of analysis that emerged existed previously nor that they were new, but rather that they represented cultural performances based on the game sessions. The game did not precisely reflect how the actors make decisions, nor did it create situations totally foreign to the participants. Rather, its value was in catalyzing performances that allowed for a better understanding of a particular phenomenon. The researchers consider that the pertinence of games as an anthropological tool is in opening a virtual channel that allows the players to analyze the cultural, economic, ecological, and social aspects of their reality. The intention of visualizing their daily actions through a game is to induce the players to view their life precisely in a “non-daily” manner. That is, the game as a metaphor for reality is intended to allow the players to enter a space of simulation and experience themselves as performers through the denaturalization of daily life. Thus, the game metaphorized their experience and diluted some borders between reality and the game, constructing narratives which were abstracted from their daily experience to later be recovered and presented as objectively real phenomena in daily life (Berger and Luckmann 1976, 61).

Although the rules of the game were developed according to the researchers’ prior knowledge of the region, the experience of playing the game showed that some rules —particularly those intended to make the game resemble real life— required modification. The players’ subjective meanings pointed out aspects of local commerce of chagra products that some players felt were not adequately represented. The experimental nature of the game lay not only in the possibility of repeating controlled sessions, but also in allowing players to suggest changes to the game’s rules. Their suggestions reveal local dynamics of chagra management that were not incorporated into the game and which can therefore be considered for future studies. Like any research tool, the game is not neutral, but rather intended to provoke in situ construction of meaning. Thus, the players’ responses were not considered to be previously determined, but rather based on a particular ontology of knowledge and of fieldwork (Castañeda 2006, 80). The chagras game was a vehicle used by the researchers to model and interpret the behavior of the players, who in turn theorized about the researchers and the study.

Conclusions

Games provide fieldwork experiences that transcend the way in which classical ethnography in traditional anthropology and experimental methods of applied sciences are conceived. Experimental ethnography makes it possible to retrospectively reconstruct the research problem based on experimental data as well as on the meaningful contexts that lead the players to recognize themselves within the mechanisms and aesthetic of the game. The game does not simply consist of decisions, but of cultural performances that reveal the actors’ situations based on the experiment and the social contexts in which they are immersed. The game leads to crossroads, represented in binary codes experienced as such only if a meaningful connection is produced among the topic, the mechanisms of the game, the interpretations of the players, and their daily life decisions.

The purpose of the chagras game was to innovate the way in which fieldwork may be conducted. The authors recognize the contributions of applied and experimental sciences with respect to the idea of “controlling” the environment and “isolating” some variables - suppositions which are the basis of research design using games. Experimental ethnographies combine these concepts of the applied sciences with the insights of the Anthropology of Theatre (Castañeda 2006, 82). Rather than an experiment that “controls” and “isolates” variables to analyze decisions, the game is a lived experience; it is a plot with its texts, scripts, and performances, a space for performance, with a juncture, some turning points, and a dialectic that spurs interest, curiosity, and revelations in the players. The performance is what happens, whether mute or audible, and consists of gestures, laughs, commentaries, and distractions; it is all part of the scene. This leads to an interesting field of research that recognizes board games as a way to represent daily life that, while “isolated” in the game, is never separated from social representations or from the epistemes of those who play, recreate, and accept playing as an interface between that which is a “game” and that which is “real.”

For anthropology, it is worth elaborating on experimental ethnographies in terms of the lived experience, which occurs upon recreating a real-life situation and experiencing it in conditions that do not place the players’ existence at risk. This lived experience is essential to establishing the game as an experiential situation in which the players play the game and “play within the play.”7 As researchers carrying out fieldwork, it is important for us to highlight that games designed with the intention of generating information make it possible to transcend the traditional way of carrying out ethnography, and if games are placed at the service of research and collaborative projects, they may help to awaken the creativity of researchers and that of those with whom research is conducted. Games have the power to unite people of any age and reveal the true nature of the actors. Although it feels like a game, playing may be as serious as living, and the game reveals the nature of the players and what they have in mind. While the players play, they must face the reality of what is “at play.”