Introduction

We live in a dynamic and changing environment, influenced by migration and other, more recent types of mobility (Pellerin, 2011), which exert substantial impact on the linguistic situation worldwide and on our national societies. These sociocultural developments call for new approaches to foreign language teaching and learning in institutional settings and beyond.

The aim of our contribution is to share the main findings of collaborative research conducted in 2013-2014, involving a high school in Luxembourg City and the University of Luxembourg. This work is a case study carried out by two researchers, one from a German-French-non-European background, and the other from a Spanish background. The research is situated in the context of teacher and researcher education in the multilingual and multicultural setting of Luxembourg, where one of the authors is preparing future teachers for their multilingual classrooms. She is also active in the on-the-job training for language awareness for educational staff already teaching in Luxembourgish schools.

In the following sections, we will discuss the specific linguistic situation of Luxembourg. There is a wide range of responses to the recent challenges raised by increased migration and mobility, and we will observe how this is reflected in the educational system. Focus will be placed particularly on so-called inclusive classrooms (classes d’insertion), an innovative setting in secondary education for recently arrived adolescent students (aged 11-12). This is also the setting of the pilot study analyzed here. Special attention will be given to theories and teaching methodologies that may impact teachers’ beliefs in the language teaching-learning process.

The specific linguistic situation of Luxembourg

Collective multilingualism and individual plurilingualism1 constitute the linguistic environment of Luxembourg, a small country of 2,586 km2 in Western Europe, bordering Germany, France and Belgium. Luxembourg has approximately 600,000 inhabitants, a very high rate of immigration (47.7% of foreigners in January 2017) (Statistics Portal of the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg, 2017), and three national languages for different official functions (Luxembourgish, French and German). Each of them is used at different stages and play different roles in the national educational system. In contrast to other countries, where each language is used in a specific region or territory of the country (e.g. Belgium, Switzerland), Luxembourg inhabitants use various languages on a daily basis and in different domains of their life (Fehlen & Heinz, 2016).

As stated in our previous research projects NATURALINK2 and LACETS3, Luxembourg has experienced very significant immigration flows from various countries (Ehrhart, 2008, 2009; Ehrhart & Fehlen, 2011) during recent decades, building on pre-existing linguistic and cultural diversity. This strong movement has created a situation of intense language contact (Ehrhart, 2005), giving rise to complex patterns of interlinguistic mediation (Cavalli, 2005), code-switching (Heller & Pfaff, 1996), and translanguaging (García, 2009). In order to describe this special situation in Luxembourg and the extremely complex repertoires of the speakers (Busch, 2012), we have coined the term multiplurilingualism (Ehrhart, 2010, p. 221). As indicated before, border-crossing between languages is more geographical in Belgium or Switzerland, and rather personal and cognitive for Luxembourg and its inhabitants, although there are also historical and geographical foundations for this linguistic diversity. Multiplurilingualism indicates that both types of linguistic diversity, the individual and the collective one, are strongly intertwined. This situation of multiplurilingualism directly affects Luxembourgish schools in their daily practice, forcing them to find ways to balance the collective multilingualism and the individual plurilingualism present in their classrooms.

According to the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages: Learning, teaching, assessment (CEFR), the development of plurilingual competence provides one of the foundations for students to achieve communicative competence in a second/ foreign language. The development of this multilingual/ plurilingual/ pluricultural competence (Cenoz & Goikoetxea, 2010), which includes among others the strategic use of skills and language knowledge developed during the acquisition of the first language, fosters the learning of a second/ foreign language in a more effective way (Cots & Nussbaum, 2003; Guasch, 2011; Hufeisen 2004; Meiβner, 2007, 2009; Bes, 2007, 2009; Bes & Carretero, 2013). In this sense, the language learning process is seen in terms of multi-competence, thus giving great importance to the internal resources that students have at their disposal when entering a new and different linguistic system (Cook, 2003; Kelly, Cheng & Carlson, 2006). From this perspective, language learning should be understood neither as a sequential addition of bits of knowledge nor as a series of watertight compartments. Instead, it should be considered as gaining a pluralistic competence by building up a complex network of interconnections between already existing knowledge and new elements. This joint development is based on simultaneity and integration (Cots et al., 2010; Guasch, 2008; Herdina & Jessner, 2002; Noguerol, 2008).

In short, by taking the development of multilingual competence into consideration, language teaching transcends the simple teaching of linguistic items. It allows students to learn how to activate their internal resources and helps them to use their own linguistic repertoire in its entirety or, in the words of Noguerol (2008, p. 15), helps them “to learn language”. Therefore, the way that teachers teach a given language and help students to learn is deeply affected by their personal teaching-learning paradigm.

Languages and the public education system in Luxembourg

An educational system based on more than one language—its historical roots reaching back to the Middle Ages (Gilles & Moulin, 2003; Ehrhart & Fehlen, 2011)—is considered essential to facilitating social cohesion in Luxembourg (OECD, 2006). This requires fluency in Luxembourgish, German, and French, with the recent addition of English, in most cases. The national policies of the Luxembourgish Ministry of Education aim to develop children’s competences in the three national languages of the country. Nevertheless, national language learning programs are quite inflexible and very compartmentalized, and linguistic skills tend to be developed in an isolated and linear fashion (García, 2009; Gretsch, 2014). Indeed, the results of the project NATURALINK indicate that the exclusive trilingualism acts as a serious restraint on the development of the country. This trilingualism should therefore be replaced by a more dynamic and inclusive plurilingualism that regards all existing languages and repertoires of the classroom in an ecolinguistic view.

In Luxembourgish public schools - starting with two compulsory years of preschool (from age 4-5) focused on Luxemburgish (with small portions of French, sometimes also German), children become literate in German in Year 1 (aged 6) and officially begin to learn French halfway into Year 2 (aged 7-8) of primary school. According to the latest statistics (MENJE, 2017), during the school year 2015-2016, 46.1% of the students enrolled in public primary education did not hold Luxemburgish citizenship. In secondary education, 21.8% in the general section and 46.1% in the technical section were of a nationality other than that of Luxembourg (see Figure 1: a, b, c).

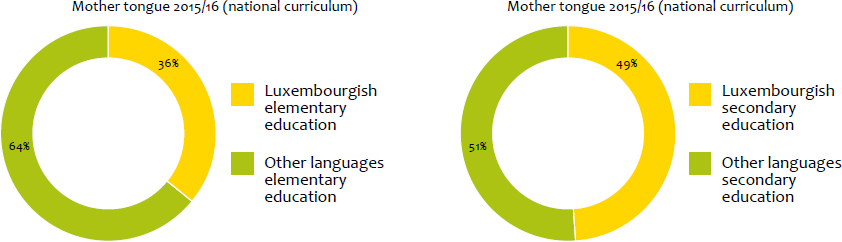

Furthermore, many of the students who do hold Luxembourgish citizenship also have other languages and cultures in their homes in addition to the Luxembourgish one. For example, during the school year 2015-2016, the mother tongue (or home/heritage language) of 63.6% of the children in public elementary schools, and 51.4% in secondary schools was not Luxembourgish (see Figure 2: a, b).

Although the data show a change in the sociocultural situation of Luxembourg, a monoglossic view continues to inform language learning at school (De Korne, 2012). The education system continues to offer only a compulsory German-language literacy program, which is becoming a problem for many children, mainly those whose home language is not Luxembourgish. There is a substantial degree of intercomprehension between Luxembourgish and German because both languages belong to the Germanic branch of Indo-European languages. However, comprehension of Luxembourgish is very limited for people whose mother tongue (or first language, home or heritage language) is a Romance language. Studies have consistently demonstrated that nonnationals, especially those using minority languages, underachieve, and blame the language gap between school and family for this (Martin, Ugen, & Fischbach, 2015).

Today’s multilingual society in Luxembourg requires new approaches for language teaching, it challenges the traditional view of language, and it needs teachers to adapt their practices to the new circumstances. In order to address this situation, the Luxembourgish Ministry of Education has called for innovative teaching methods. One of the measures implemented in secondary schools are the so-called inclusive classrooms (classes d’insertion). These inclusive classrooms address the existing linguistic diversity in the classrooms. They are designed for recently arrived adolescent students (aged around 11-12) who lack knowledge of any of the three school languages. This special track offers newly arrived young students at the secondary level an opening towards higher education levels by means of a full-immersion program in only one language (French, German or English). The language chosen for schooling is then considered to be the second language of the respective student.

Beliefs & Practices

What the teacher teaches is not always what the children learn (Ellsworth, 2005; Arostegui & Louro, 2009; Kohn, 2008). Children learn through a variety of educational and social contexts. Children learn anytime, anywhere, and continuously, without interruption. For their part, teachers usually decide how to teach depending on the context, the curriculum, the space, the time, etc., but also according to their own individual and personal characteristics such as age, gender, personality, self-esteem or identity (Bernat & Gvozdenko, 2005; Burguess et al., 2001); learning experiences (Busch, 2010; Abreu, 2015); practices and working experiences (Burguess et al., 2001; Levin & Wadmany, 2006).

In general, teachers hold beliefs (as well as attitudes, judgments, ideologies, perceptions, and conceptions, see Andiliou & Murphy, 2010, quoted in Chan & Yven, 2014, p. 110) about their roles, their responsibilities, their students, their pedagogy, etc., all of which influence their consciousness and practices as well as, in turn, the students’ learning processes and achievements (Coplan, Hughes, Bosacki & Rose-Krasnor, 2011; Espinosa & Laffey, 2003). It is usually accepted that teachers’ beliefs work as filters for teachers’ instructional and curricular decisions and actions, and can thus either promote or impede change (Prawat, 1992). Therefore, teachers need to be aware of their own beliefs in order to be able to open up to any change (Klapper, 2006). Teachers use a variety of approaches to enhance student learning, but in light of the above we need to ask: Does what teachers think they do correspond to what they really do? The relationship between beliefs and practices is complex (Li, 2012). Aksoy’s literature review from 2015 quotes studies in which various degrees of congruence between beliefs and practices are found.

The present case study

The present case study aims to develop research on the complex topic of linguistic and cultural diversity in the innovative multiplurilingual teaching context of Luxembourg. Specifically, we focus on the particular case of the inclusive classrooms, a format that may provide information that is also useful for other settings in Luxembourg (and beyond). Considering the teacher as a mediator of learning, and grounded in the sociocultural theory combined with an ecolinguistic approach, the present study describes the way two secondary school language teachers teach French in two inclusive classrooms in a public high school in Luxembourg. In parallel to the description of their practices, we also present their beliefs and ideas about their teaching. We also intend to evaluate their contribution to social cohesion through a co-construction in the structure of Luxembourgish society.

The study draws on data from two inclusive classrooms (7th and 8th grade) for newly arrived students, following an official itinerary for first and second year of secondary education in French. Study participants include two female teachers who taught French Grammar in an intensive way (13 hours for a total of 30 hours of class per week), as well as their students (aged 11 and 12), whose other teaching units also use French almost exclusively as the language of instruction. Teachers were selected on the basis of their teaching experience and willingness to take part in the study together with their students. In fact, this research was requested by the two French teachers, and had the full support of the high school administration. This fact seems very significant to us since the motivation for conducting this study came directly from the stakeholders themselves. Both, the high school and the two participating teachers, were already aware of the existing multiplurilingual situation—the great number of languages present in their classrooms as well as in the children’s individual trajectories (see Appendix 1). Moreover, regular high grades in French achieved by the students who attended these particular inclusive classrooms were becoming popular in the country, leading to newspaper articles and attention from the Ministry of Education for this special setting. The two teachers, henceforth referred to as T1 and T2 to ensure their anonymity, wanted to learn more about their way of teaching French in this multicultural context and to share experiences with their practices, as they could be of interest to other teaching environments in the country. Based on these ideas, two main objectives were set for our research:

To observe and describe the way the two teachers of French were teaching in these inclusive classrooms.

To discuss and reflect with the teachers the way they thought they were teaching.

By means of periodical classroom observation (one session every two weeks), audiorecording, field notes, and photos, we documented what was happening in class during one academic year (October 2013 - July 2014). The total length of time spent with the two groups represents 9% of the time that a student stays in class in one school year. This means that the information we have, although very valuable, represents a small segment of what happens during the process of teaching-learning French inside the classroom. From previous longitudinal projects with classroom observation, we know that not everything can be observed, but this degree of time intensity enables us to provide an accurate representation of the overall activities during the school year.

By means of two 90-minute semi-structured interviews conducted with the two teachers together we gathered information on their beliefs and thoughts, on their practices, and about the children’s learning process, at two different moments of the school year (13.01.2014 & 21.05.2014). These interviews were audio-recorded with the permission of all participants and transcribed into written form, using standard punctuation marks. For the purposes of this paper, we translate the original language of the participants into English. French was used by the teachers most of the time, with few elements in other languages (when translating the text is written in italics; when special attention to certain elements of the text is required, the use of bold is added). No information about non-verbal communication was included in the transcripts. After several readings and revisions, we used a thematic analysis to identify the main themes of discussion. All data were treated anonymously and respectfully following the ethical principles of the University of Luxembourg and the national regulations in force in Luxembourg.

Observations of practices and beliefs

In what follows, we describe in a condensed way our longitudinal observations throughout the year in both groups and with the two different teachers working strongly together in the methodological preparation of their classes, including their agreements and disagreements about their practices.

Teaching of French and in French within the two groups

The following description of our observations is focused on classroom interaction between teachers and learners, considering the structure of participation. Both teachers controlled the interaction at all times, promoting a kind of interaction that can be characterized as asymmetrical (Van Lier, 1996, 2004). Learners participated when teachers called on them by saying their name. At all other times, they had to wait until they were called, or had to raise their hand.

According to Van Lier (1988, 1996, 2004), the most common pedagogical discourse is based on a three-part exchange including: an Initiation, a Response and a Follow-up (IRF/ dialogic talk); it is balanced or symmetrical in terms of rights and duties of speaking, not in terms of equality; and it is more topic-oriented (content) than activity-oriented (product). The greater the student’s freedom to determine and contribute to the content, the greater the presence of contingency. However, the reverse is also true: “the greater the contingency, the greater the power to engage in conversation-for-education” (Van Lier, 1996, p. 167, quoted in Taber, Sumida & McClure, 2017, p. 113). Teachers who are aware of the importance of promoting contingency should explore, analyze, and discover how interaction in their classrooms occurs and act accordingly. By implementing the analysis model developed by Bes (2007), teachers and teachers-researchers may gain the opportunity to achieve a better understanding of what actually happens in class, a better way of understanding how communication takes place between them and learners, and a better grasp of the way that they teach and of how learners learn the language within multilingual and multicultural contexts.

Both teachers controlled what they had to do at each moment. They had an agenda to accomplish, partly because of their tight curriculum, and they managed and distributed the time for each activity. Time pressure was even more evident in the 7th grade than in the 8th grade, where they worked fast and one activity followed another without interruptions. Sometimes, it was possible to observe how teachers, focused on their agenda, lost opportunities for teaching the language coming from the students or the class in general. We noticed that discipline and order were very important components of classroom interaction in the two groups. These points were of great concern to the two teachers, maybe influenced by the presence of the researcher observing their classrooms. Students knew that they had to follow the rules when they wanted to participate in class. If a student forgot the procedure, he or she got into trouble. In fact, we observed a change in some students’ attitude from the beginning to the end of the school year. Among all the students, the most spontaneous, participative, talkative, active, motivated learners at the beginning seemed to be quieter later on, even apathetic and disinterested in the language. Thus, cultural differences in the accepted way of acting in class can constitute a problem for newly arrived children if no one explains to them how they should behave in this new context.

Overall, students in both 7th and 8th grade did not have opportunities to interact/ work with other students. During the observations, students interacted only with the teacher. The only way of grouping the learners observed was working in group-class, always plenary (in turns) or working individually, in silence. T1 clearly supported this idea during our second interview and justified it by referring to it as a matter of age. For her, the students could not work in groups because they were still very young: T1: And group work (…) this is something that works better when they are in 10th grade, because they are more mature; the little ones do not know how to manage the time nor??? (T2: Yes), nor to split the tasks. (…) In fact, research has shown that, in general, the little ones are not receptive yet. Therefore, when there is some maturity, they can better benefit from that. T2 agreed with her colleague, although she seemed a little more flexible: T2: [group work] between the students and us, and among the students. [Interview translated by the authors, 21.05.2014].

When it comes to interaction, we also need to consider space. In both groups, we observed a spatial distribution based mainly on frontal teaching. Learners sat in rows, looking towards the front, and the teacher’s space and the blackboard presided over the classroom. In fact, the students metaphorically described being in class as “watching TV”. Both teachers did not agree with this idea at all and expressed their disappointment when we referred to their teaching as frontal teaching. For them, to be at the center of the interaction was related to organizational issues and not to teaching-learning strategies. Discipline, as we said before, was very important to them, and they thought they had to keep control of the group at all times. To them, this was the reason why they were at the center of the group. In fact, they considered their practice with their students very interactive, and they mentioned laughter and joking as proof: T1: “Frontal” I completely disagree. T2: We do not teach in a frontal way. T1: Frontal teaching is something different. (T2: something different) (…) because when there is an interaction between a student and the teacher, the other students also participate. Maybe they do not participate like this, but like this. Researcher: “like this” you mean through you? T2: Yes. Because they wait for permission in order to talk. T1: Frontal teaching is like when only the teacher talks and the others are listening (9 seconds pause). Here, they intervene. (…) T2: For me, the course is very interactive, because the students talk all the time. T1: There is a lot of interaction, we laugh a lot. [Interview translated by the authors, 21.05.2014]. It is interesting to note two things happening here (see underlined segment of excerpt): first, the silence created by the pause of 9 seconds until communication was restarted may indicate that this was a controversial issue for the teachers; second, there was a notable change of languages. T1 repeated her previous explanation in French in English, maybe to ensure that everybody had a clear understanding of her ideas.

According to our observations, students were free to participate in class but on the condition of raising their hand first. Some students participated frequently, while others did not participate at all. Both teachers constantly asked the students who raised their hand, but the others were not encouraged to intervene. Thus, interaction was not distributed in a balanced way in order to invite all of them to participate.

Diversity management for languages and cultures, attempts to integrate elements other than French into intercultural classroom communication

The following observations refer to the teachers’ claim that they had made a special effort to integrate elements from different languages and cultures into the classroom.

The linguistic diversity in both groups was not used as a regular teaching strategy for learning French. For certain types of vocabulary activities, teachers invited students to translate into their languages (in this case, the teacher helped them by using Google Translate). When we asked them specifically about how they managed the cultural diversity in their class, they laughed and referred to the idea of “family” as a strategy for inclusion: Researcher: Do you do something to integrate these cultures in the group? (…) Do you have any strategy? (T1/T2: laughs) Any conscious strategy for teaching them? T2: There is not any strategy (…) We try to translate in the languages they speak. T1: This is the strategy. (7 seconds pause). The strategy is??? They find a new family. T1: Or, there are also translators. Researcher: Google. T1: Google, yes. [Interview translated by the authors, 21.05.2014].

Overall, we did not observe the use of specific strategies to promote plurilingual competence. For example, students were also learning English and Luxembourgish, but the teachers did not use them as instructional tools for learning French. Moreover, the use of other languages in class was not considered as a resource. In most cases, despite the plurilingual background of the students, teachers tended to promote monolingual strategies for language teaching (only French). Canagarajah (2011, quoted in Hansen-Pauly, 2014, p. 29) underlines that “[l]earning as a participant in a multicultural community, with the classroom as common space, is part of the process of social cohesion and citizenship education”. It is therefore necessary to shift our emphasis “from language as a system to language as a social practice, from grammar to pragmatics, from competence to performance” (Canagarajah, 2006, p. 234, quoted in Hinkel, E., 2017, p. 39).

Choice of activities that foster learning a new foreign language that is both the language of instruction and the subject

With respect to content, during the time spent in both classrooms, we observed the following activities and distribution in each group (see Figures 3 & 4).

Grammar and vocabulary are the most common activities observed in class, although the amount of grammar activities decreased in both groups as the course progressed. In contrast, reading and oral presentation in 7th grade, and listening comprehension and reading in 8th grade, were less frequent. Reading was an activity for specific moments, for example when students were tired. Moreover, both teachers agreed that they usually do a lot of grammar, practical exercises where students can apply what they have learnt in class, and interactive activities like role play: T1: There is much more grammar, there is much more… exercises, practice… T2: Practice. All that we do… we do…, there are interactive exercises, role play. [Interview translated by the authors, 21.05.14]. Some of these activities did not take place during the time we observed these classes. This might be due to the presence of the researcher as an element that disrupts their normal routine. According to the observer’s principle, the presence of the observer affects the setting. For this reason, teaching units with new items tend to be avoided, because they carry the risk of unforeseen scenarios.

Although speaking (naturally and spontaneously) in class was not very sustained through the oral interaction practices implemented, students were able to speak French fluently. Considering the time students spend in school per day (approx. 37% of their day time), French seems to be acquired not just inside but also outside the classroom. Both teachers were aware of this idea, although they emphasized the importance of learning the language in formal contexts: T1: Of course, they practice outside the classroom. But I think they learn a lot by taking a French course. (T2: Yes) The activities are highly varied. [Interview translated by the authors, 21.05.2014]. The interaction observed between teachers and students was very rigid. Learners participated in very controlled interactions, guided by instructions or a specific objective. The result was an artificial discourse, consisting of reading the answer, repeating the sentence, filling the gap. Rather than speaking in French, students were invited “to say it in French”. However, when students were invited to participate in more open and relaxed interactions, learners showed a very good command of the language. Students could speak French. Moreover, students from 7th grade could talk in French quite fluently before the end of their first year of instruction.

When we asked the teachers about their approach to language teaching, they considered their approach was different (that is, different from the approach taken by other teachers, based on more traditional approaches and methodologies), but they were unable to explain it: T2: This question is very difficult for me. I cannot explain to you how I teach. I teach! (laughs). We have our teaching materials. Why is our way different? Eh… I do not know. T1: In comparison to other normal high schools, their teaching is more classic… T2: Our teaching is not traditional, that means we do not read page by page, we do not write on the blackboard and the students just copy. We try from the very beginning to make them participate. Our lessons are very interactive. Kompetenzorientiert. Our work is based on competencies. T1: (…) The traditional approach is very far from real practice. (…) Researcher: When you talk about a traditional approach, what do you mean? T1: You should see the books they use in the Luxembourgish system. You learn everything by heart and that is it. And do not think, and do not create, just learn. Stop it. [Interview translated by the authors, 21.05.2014]. It is interesting to observe how code-switching is used by T2 in order to develop her thoughts, as the use of different languages indicates different metalinguistic levels: German for a short quote from the national teaching regulations, French for the description of the activities, and—from time to time—English, especially for meta-levels of analysis.

Findings

The analyzed data show the impact of the teachers’ beliefs on their classroom practices and their pedagogical decisions. What teachers think they do sometimes does not fully match the practices observed in their classrooms. In order to make those two ends meet, teachers need to develop their talent as researchers and reflect on their practices in order to find new pedagogies and approaches to education in multicultural contexts.

New spaces and opportunities are needed for teachers to reflect jointly and discuss their practices. The model displayed in Figure 5 (see below) was developed in our work with future teachers. It shows how the different activities in the educational field are linked. The contexts of teaching and learning can be seen as the starting point, whereas their observation through research can help raise awareness of the educational process and find innovative approaches to teaching and learning. These insights influence educational policies to varying degrees, according to the impact and relevance of the innovation recognized by the authorities. They can then again be introduced into teacher education and will then disseminate into the schools and their contexts of teaching and learning, carried by these new teachers.

Figure 5 -

A Holistic View of Dynamic Flows in Research and Education. (Ehrhart, Teacher Education Unit for Primary and Secondary Schools in Luxembourg, 2012-2017)

Finding new ways to introduce language awareness into the classroom, especially through teacher education and the development of new models of bilingual education and teaching materials, is not sufficient. Looking at highly mobile families, we observe that the children themselves are important vectors of innovation. Instead of using their high potential to foster classroom interaction, they are frequently seen as problematic, especially when they have to integrate into monolingual schools or schools that still retain elements of a monolingual habitus in a generally multiplurilingual setting of society. Teaching and learning have to take place at the same time on both the teachers’ and the students’ side. In doing so, the challenge for schools and educators worldwide is to recognize and acknowledge the variety of languages and language combinations among their students.

Whenever the repertoires between teachers and learners diverge substantially, and particularly when the students have knowledge due to their life experience in extremely mobile contexts, they can act as peer teachers. In some cases, even learning tandems could be created in which the roles of teachers and learners are situationally switched according to who the expert is in a specific field. Our observations show that this creation of tandems does not weaken the authority of the teacher but fosters the general learning process based on attitudes of justice, inclusion, and openness.

Including teachers, not only speakers of Luxembourgish and citizens of the country, in the educational system can also enrich how the classroom is conceived. Valuing professionals in education because of their general knowledge and not only because of their linguistic repertoires can help bridge the gap between the seemingly homogeneous group of teachers and the heterogeneous group of learners. Furthermore, promoting parental involvement in school can have positive effects on their children’s learning process. Families need to be seen as valuable pedagogical resources that can help teachers to better understand and manage the diversity in their classrooms. They can provide elements to build bridges between the different cultures and thus create a new home for the children in which their former experiences are also highly valued.

We are well aware of the fact that innovation and change of teaching practice takes considerable time and effort. French language teaching practices outside France tend to follow very traditional patterns (and the teaching of French to non-natives in general, also in France), and Luxembourg is no exception. The change to be introduced might apply not only to the teachers’ practice but to the general approach to teaching this language for second and foreign language learners. In particular, teachers of language (a grammar-based approach) and teachers in language (using the language in a vehicular function for pupils still undergoing the process of acquisition in precisely this language) converge in the case of Luxembourg. Currently, teacher education in Luxembourg is aimed at supporting and developing teachers of languages, i.e., teachers of Luxembourgish, German, and/ or French. Due to the social characteristics of the learning environment in the country, however, teachers need to adapt their initial competencies as language teachers and become teachers of content in the language they teach. Initial teacher education needs to be reshaped to help teachers understand and be conscious of the double role they play when teaching languages in the multicultural context of Luxembourg.

The authors’ background—German-French-non-European and Spanish—and their experience in various countries with different teaching models, offers an advantage in the task of observation, namely the distance to the school system being observed, since they did not experience it from the inside, neither as students nor as teachers. It leads us to the conclusion that what might be considered an innovation for some students with a specific background might not be for others. For instance, the authors could observe that the most active students became quieter during the year. For this reason, a broader range of teaching activities might be able to offer opportunities to different student profiles, including those closer to the teachers’ experiences and those more distant to their way of communicating in the classroom. The same kind of distortion also comes into play if the research team does not possess an intercultural component, including various members of different origins. Of course, this bias can never be avoided completely.

Finally, by activating the multiplurilingual approach for all actors involved in the process, potential communicative gaps and triggers for misunderstanding could be addressed, discussed or even avoided. This means that young people do not necessarily have to find a completely new family (T1: they find a new family), but rather a new branch to their already existing and thriving family tree.