Introduction

Armed conflict in Colombia has left consequences on victims who keep a variety of experiences that deserve attention in educational settings. This article discusses a study about student-victims’ conflict experiences in memory artifacts as an alternative of healing and resilience. This means memory artifacts were developed and analyzed as a resource through didactic sequences aimed at collective repair of participants’ traumatic memories as victims of the armed conflict (Blair, 2011).

As victim students’ experiences have been the effect of violent situations such as rape, murders and threats, we can identify consequences such as mental and emotional traumas in this population. Some studies conclude these conflict-related facts provoke illnesses including sleep disturbance, revenge and anxiety (Centro Nacional de Memoria Histórica [CNMH], 2013). That is why this project sought to contribute to the overcoming of those feelings in a short and midterm as part of an ecological pedagogy (Creese & Martin, 2003).

The apparent lack of healthy educational spaces where victims can express their experiences in a post-conflict setting constituted the research problem we identified in a public school. There victim students seemed to be excluded through forgetfulness and abandonment. After entering and observing an educational environment for victims of conflict such as Embera students, it was concluded there were no alternative spaces planned or allowed for them to express themselves and heal conflict sequelae.

In view of the above, we proposed the following question: What memory artifacts do students as victims of conflict construct through a didactic sequence towards peace education in an at-risk EFL setting? Hence, we analyzed and interpreted the content of artifacts elaborated by victim-students when participating in English didactic sequences for resilience purposes. Discourse analysis strategies (Wodak, 2013) were applied to comprehend victim students’ experiences within the armed conflict, so that they could construct resilience spaces and identities with the other. In the present manuscript, we will explain the research problem, followed by the theoretical framework discussion, the research methodology, and the pedagogical intervention. Finally, we will display our findings and conclusions.

Problem statement

Colombian armed conflict has had a significant influence on education due to events such as political persecution that have affected various social leaders, teachers, students and so on (CNMH, 2013). According to the Grupo de Memoria Histórica (CNMH), some of these acts have even involved “destruction or misuse of public education infrastructure” (2013, p. 277). Conflict has thus impacted educational scenarios where learners become another group of victims of conflict.

After approaching a public school in Bogotá as an at-risk setting at risk, we identified that children as victims of conflict may lack dialogical spaces to manifest their underground memories (Blair, 2011). These children who surrounded such conflict spaces were forced to witness concurrent punishments and public torture that could generate deep emotional impact on them to the extent that their psychological resources appear as undermined (CNMH, 2013).

Nowadays, those victims of conflict may find difficulties to make their lived experiences visible, even in educational settings such as the EFL class. During the interview with the primary school teacher of the institution, she stated there was a lack of spaces where victim students could express their experiences in a post -conflict setting. She added that dialogical spaces for victims of conflict depended on teacher’s intention or good will (Excerpt 1). Teachers’ pedagogical knowledge and interest in affording these victim students with the setting towards peaceoriented didactics was a personal choice, rather than an institutional effort (Excerpt 2).

Excerpt 1

MXXX: That playground space is interesting, is it enough or do you think there’s something missing?

JXXX: Yes, of course. But that depends a lot on the teacher. Let’s say that public institutions give you a certain academic freedom so they demand some results from you, but you close the door in your class room and you’re the one who decides or with your children you build what you’re going to do.

Excerpt 2

There is the teacher who all day is with guides and books, who is concentrated in academic objective, there is the teacher who interacts with children. So it also depends a lot on (…) teacher’s intention, unfortunately. Because, yes, many teachers are going to say no.

The problematic situation raised the necessity to create spaces that fostered victim students’ expression in a post-conflict context through a didactic sequence. We posed the research question: What memory artifacts do students as victims of conflict construct through a didactic sequence towards peace education in an at-risk EFL setting? Accordingly, our general research objective was related to interpreting victim students’ memory artifacts as products of EFL didactic sequences in an at-risk school setting. These artifacts in turn allowed for a dialogical space, in terms of Meijers, Lengelle and Kopnina (2016) in an EFL class.

Theoretical framework

This study is framed within the field of Applied Linguistics (AL) in English language education for peace. In this section, we account for three constructs. Firstly, Memory artifacts comprise two types of memories: namely, dominant and underground (Pollak, 2006). The former refers to the official version which is public and well-known in society. The latter is focused on traumatic experiences narrated at specific moments; these are orally communicated from generation to generation. Therefore, underground memories tend to enact the dominant ones, usually imposed by official discourses. Additionally, da Silva (2010) explained that underground memories are often forgotten or ignored, since the living experiences attached to them do not come from an official institution. Da Silva (2010, p. 6) also specifies there are two further memories: namely, “longs” (based on violent happenings) and “shorts” (violent experiences limited to the military coup).

Along these lines, Blair (2011) defines underground memories from the lexical and semantical point of view. This scholar argues this kind of memory properly reflects the inner set of victims’ experiences. Besides, this sort of memories plays the role of instruments that allow victims to unearth and make the silent anecdotes perceptible through visible devices, in order to display the existence of power spaces existence (Blair, 2011). In other words, the term memory may refer to an artifact (Blair, 2011) and a pedagogical narrative mechanism (Butcher, 2006). Conceptualized as such, memory allows for power and change management which gives victims the opportunity to recover and heal their experiences stored as destructive memories produced by the Colombian conflict.

Experiencing armed conflict in Colombia

When we talk about conflict in Colombia, victims’ voices need exploring. The term Victim of the conflict refers to a person who has experienced a series of traumatic events in the armed conflict such as rape, killings, and forced displacement, among others (Akwenyu, 2012). These events leave emotional and psychological sequelae. The CNMH (2013) asserts there is no discrimination when identifying effects of conflict and violence. This encompasses children are also one group highly affected by these events. Most of this population develops feelings of melancholy and sadness, insofar as they experience loss of loved family members (CNMH, 2013).

This type of victims displays a series of primary and secondary effects because of conflict sequelae, which range from sleep disturbance to unhealthy habits (e.g. addiction to toxic substances) as said by CNMH (2013). Besides, there is another entity that alludes to the deranged development of personalities. This is mainly caused by exposure to life in cities where there might be contempt, shame and even rejection when facing the other and their different circumstances (Akwenyu, 2012; CNMH, 2013). Otherwise, spaces for resilience where victims may re-elaborate their experiences through dialogical learning could be “engaged in examining social issues” (Contreras & Chapetón, 2017, p.137) such as the Colombian armed conflict. According to Meijers, Lengelle and Kopnina (2016), this type of dialogical learning “attaches meaning to experiences in both conscious and unconscious ways” (p.1). Therefore, it may change when interacting, directly or indirectly, with external entities such as family, classmates, teachers and so on. This affects one way or another these emotional impacts caused by the Colombian armed conflict. These underground memories experiences (Pollak, 2006) are expressed through memory artifacts.

Moreover, Blair (2011) asserts that the underground memory “by the semantic content of the word […]reflects quite well the invisibility of these memories built in pieces, scattered”(p. 65) and they may be reincarnated or exposed through artifacts or devices of memory. These are provided as materials that work as a positive mechanism for the expression and exhibition of ideas about the post-conflict, peace and forgiveness (Blair, 2011). Besides, they facilitate the “informal acquisition of communicative competence [of L2] through communication activities such as discussions, projects, games, simulations and drama” (Carter & Nunan, 2001, p. 9). In sum, memory artifacts are emotionally oriented material which could be implemented in a resilient way. Therefore, victims are participants of dialogical processes, which allow an exchange of experiences (underground memories) that promote a healing introspection.

Contrastively, as Barón (2015) indicates, victims of conflict can use negative experiences as a transformative mechanism. In doing so, victims become active subjects in the society, inasmuch as they transform their conflict-generated experiences into a construct towards peace communities. In some cases, victims can overcome the aftermath of the conflict. All of this occurs from a self-recognition process in the search for the recovery of non-official or underground memories (Pollak, 2006). Thus, memory artifacts promote dialogical spaces for self-recognition towards the re-elaboration of victims’ experiences (Blair, 2011).

Victims of conflict seem to hold both the conditions and resourceful experiences to heal themselves (Restrepo, 2016) under the support of societal institutions. With that in mind, victims can exploit the ability to transform their sequelae into a constructive version of conflict events. This practice becomes a basis for the ethics of recognition (Jimeno, 2010). Subsequently, victims gain active and sound participation within the civil society. Emotional ties may lead different people or acts of resilience to a politically active subject (Barón, 2015). For instance, Restrepo (2016) argues that women victims of conflict “have found diverse ways to overcome their victimizations and traumas” by “joining or creating victims’ organizations and helping others to realize they can also be part of their own complex healing process” (p.7).

In educational contexts, victims of conflict can benefit from dialogical learning which implies a pedagogical approach founded on conversational strategies and mechanisms to find and propose solutions to social situations (Contreras & Chapetón, 2017). In other words, Contreras and Chapetón (2017) assert dialogue activities encourage teachers and students towards analysis and participation in social issues through conversations, based on experiences and background knowledge in the Colombian conflict.

In addition, Meijers, Lengelle, and Kopnina (2016) argue that there is a polyphonic subject who combines two voices (internal and external). Subjects use those voices through language and dialogue. Victim students’ experiences can thus be re-elaborated through different voices when exposed to external entities affecting internal voices. This can help them to materialize memories in artifacts understood as materials and spaces of power (Blair, 2011). These artifacts take place through resilience and reconciliation processes which may be recognized as constructs of peace and forgiveness (Vargas & Flecha, 2000).

Peace education for complex English teaching

In relation to this construct, it is necessary to approach the different definitions given to the concept peace education in diverse communities by multiple scholars. Certainly, each community has perceived peace construction from particular worldviews and contextual needs, values and principles attached to cultures (Harris, 2004; Oxford, Boggs, Turner, Ma, & Lin, 2014). Indeed, lots of violent situations in humans’ history, including war, environmental disasters, genocides and others have been experienced, understood and tackled differently by each society through particular alternatives that broaden the peace education growing field. According to Harris (2004), peace involves postulates from which approaches or types of peace education emerge. Within this view, peace theory is usually connected to peace practice.

Generally, postulates in peace education involve: “explaining the basis of violence, teaching alternatives to it, adjusting to cover different forms of violence; varying according to the context and holding the idea that conflict is omnipresent” (Harris, 2004, p. 6). As a result, this scholar identifies 5 types of peace education: international, human rights, development, environmental and conflict resolution (Harris, 2004; Kruger, 2012). Albeit all of them may be relevant not only in the case of our participants but other settings in the literature reviewed, the last one seems more important for us because of participants’ profile. Harris (2004) and Kruger (2012) define the conflict resolution type of peace education as the teaching of tactics to provide solutions to daily dispute. Conflict resolution educators model communication skills that may remain key for survival in a postmodern world where a healthy family is placed as the core.

Interestingly, conflict resolution education allows students to understand conflicts basis, causes, consequences and participants involved to manage everyday problems (Harris, 2004). This approach and type of peace education is oriented to the social and interpersonal link constructed and maintained through social skills (Harris, 2004; Sánchez, 2010; Tudor, 2001). These in turn embrace self-control of emotional impulses and feelings behind violent behaviors (Harris, 2004). The chief advantage of this approach relies on the fact that students can apply it to everyday settings and issues by employing non-violent alternatives (Sánchez, 2010).

If peace education can respond to everyday life from the conflict resolution stance, it is possible to relate it to the complexity perspective where chaos and “disorder” are not only present but considered as part of human life (Maldonado and Gómez, 2010). Conflict and peace orientations in humans constitute complex phenomena and they also deserve attention from a transdisciplinary a lens (Aldana, 2015), including Applied Linguistics to ELT. Indeed, languages such as English, Spanish or Native languages support communicative strategies victim students could unlearn and relearn towards conflict resolution. Estaire and Zanón (2010) argue English constitutes a resource to build up interpersonal relationships and keep these social links. Tudor (2001) discusses the possibility to consider language as a resource for building up social relationships and as a self-expression tool. Learning, teaching and using language for these purposes overlap the construction of peaceful solutions of problems within an English class beyond instrumental trends in ELT.

Similarly, Oxford et al. (2014) propose a concept that refers to the hybridity of peace education as related to victim students’ complex aspects of life. These scholars explain how a myriad of dimensions underpin peace and make it diverse. More specifically, this multidimensional peace is directly connected to a person’s inner peace (intrapersonal life dimension): an interpersonal peace with other individuals (Oxford et al., 2014). These researchers point out the dynamic nature of this multidimensional peace as encompassing an everlasting search for harmony distributed in life dimensions which come out in different places or settings as educational ones.

That is why ELT as a complex field has experienced a transition that goes beyond the discipline academic knowledge. At this point, teacher researchers become aware of the scope and role ELT actually has in peace from its already identified and emerging versions. Vasilopoulos, Romero, Farzi, Shekarian, and Fleming (2018) examined the practicality and relevance of positive peace included in a three-month teacher program directed to rural teachers, and by considering the idea that ELT is a political act too. Results displayed both visiting and host teachers’ negotiation about pedagogical approaches to peace education and EFL local curricula worked as sites for peacebuilding. This was because equitable and just teacher education was delivered when rechallenging hierarchical structures to transmit knowledge in teacher professional development courses (Vasilopoulos et al., 2018). This means privileging negotiation among peers, as opposed to pupils. In this case, a link between peacemaking and ELT is exploited from teacher education perspectives as the practice to contest hegemonic forces in EFL and urge periphery teachers to be critical about it. Needless to say, we, as researchers, decided to adapt the teacher negotiator role for this research proposal.

Along these lines, language is attached to culture (Kramsch, 2013) which, in turn, is constructed and weaved through life; in this case: victim students’ life. Not only can English language then facilitate victim students’ communication practices in their lives, but it can also potentially support the construction of small peace cultures that “enable peaceable behavior to take place” (Oxford et al., 2014, p.6). In conclusion, ELT and peace education are not excluding fields of theory and practice; on the contrary, they inform each other about outdoor phenomena to have an impact on victim students’ lives.

Methodology

This study was qualitative, and it connected strategies from the descriptive and interpretive research designs. Firstly, reality interpretation was dynamically conducted from transdisciplinary perspectives (Cohen, Manion & Morrison, 2007). We were more interested in understanding reality than measuring it. Secondly, our data collection methods gathered qualitative data (students’ interactions and re-elaborated experiences). These methods were observations assisted by semi-structured field notes and students’ artifacts. Thirdly, a purposeful sampling technique was applied and we selected 14 students as victims of the Colombian armed conflict; they all studied at a public school in an urban setting, they had low socioeconomic status, and they came from the Emberá indigenous community. In terms of language, they were able to communicate in Spanish to a certain extent; thus, they employed their indigenous Native language too, which was the Emberá one. These children were in fifth grade and their ages ranged from 11 to 13 years old.

Specifically, we approached the setting by participant semi-structured observation to identify some contextual conditions surrounding the educational setting. This was complemented by field notes when observing the in-class environment to focus on victim students’ communication practices and interactions. Secondly, we designed five didactic sequences to approach victim students inside the English class. Topics such as “home”, “animals”, “family”, and others were proposed in didactic sequences (Harmer, 2008). We presented activities to appeal students when lessons started. Afterwards, we explained main topics (usually lexical, implying life events and students’ experiences) through questions for students to relate these words to their backgrounds. We were based on questions used by Blair (2011) in her study since her research context is applicable with ours (fifth grade students). During the intervention we used questions such as: Have you ever had a pet? How is your house? Describe it, do you recognize this sound? What place comes to your mind when you hear this sound? and so on. Moreover, each sequence was developed in four stages: the first one consisted in introducing the main topic; in the second stage, we introduced the oriental questions; the third step was about the construction of memory artifacts; and finally, there was a dialogical space to re-build their armed conflict experiences. In addition, it is necessary to clarify that this is a pedagogical prototype which could be used by teachers from different areas.

Consequently, we triangulated data appearing in our field notes during participant observation with the other data in victim students’ artifacts. To achieve so, we managed data in tables while numbering and coding them based on participants’ names initial letters simultaneously. In doing so, Grounded theory approach for data analysis was applied (Cohen, Manion and Morrison, 2006). It is worth adding victim students were involved in the first key stage of Grounded theory known as naming, according to Freeman (1998). This was because victim students’ voices were considered relevant for data interpretation around their own experiences re-elaborated in an attempt to understand these phenomena from multiple eyes, and not only that of the researchers’ in a top down perspective. Various scholars as Cohen, Manion and Morrison (2006, p. 34) support it from the Complexity theory which calls for “multiperspectival approaches” to look at reality.

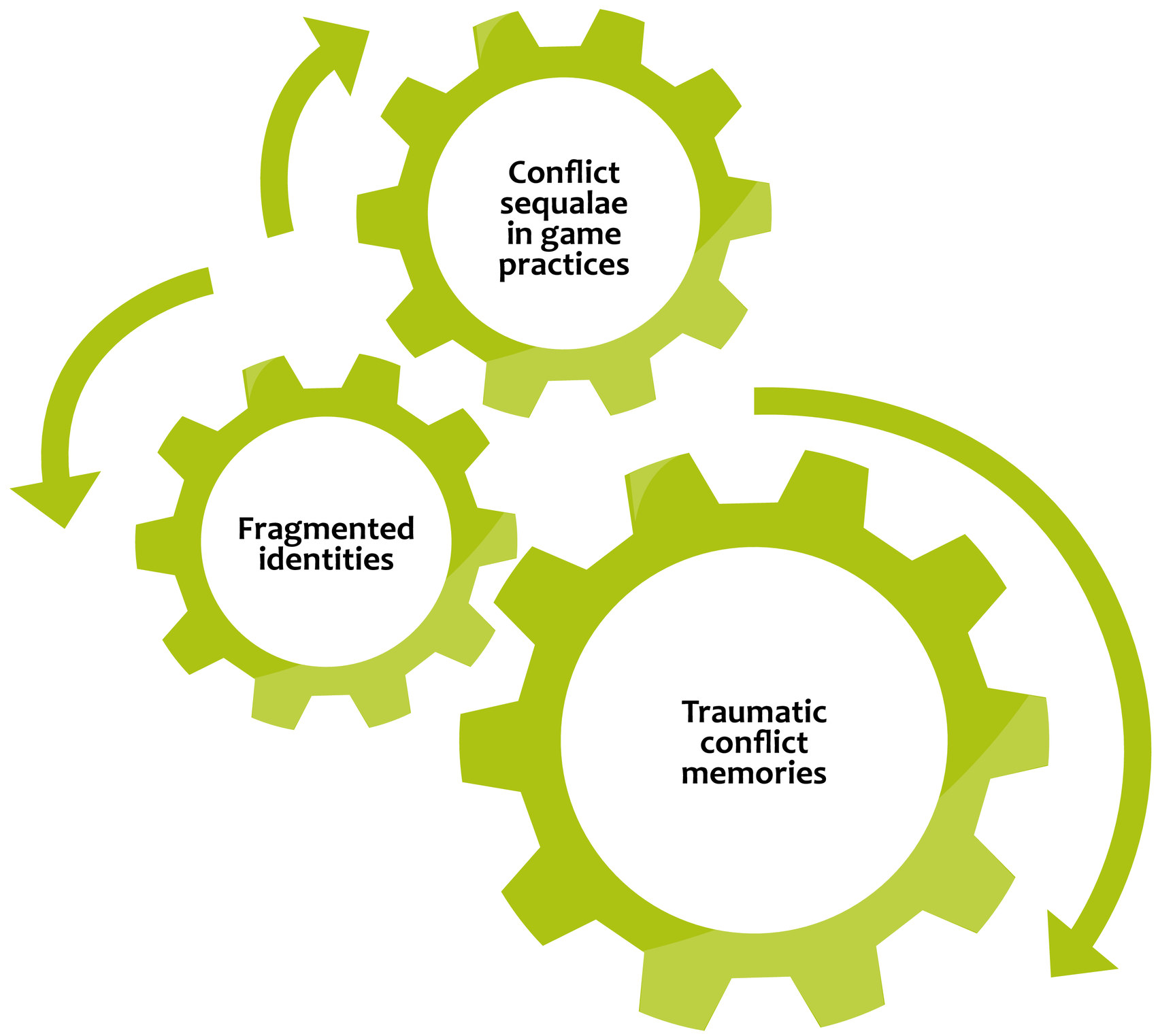

Once applying didactic sequences and collecting data for answering the research question, we managed data in tables through transcription, numbering and color coding. Grounded theory approach for data analysis was used (Cohen, Manion and Morrison, 2006). Consequently, three categories emerged as our research findings to answer the question. We represent this study findings through the following categories from an enclosing relationship (Figure1).

Traumatic conflict memories

Memory is the deposit of experiences stored through time (Sherwood, 2014). Additionally, memory is affected by people’s experiences and situations (Halilovich, 2013). Memories are thus internal, but directly influenced by outside situations or events. In the case of participants, forced displacement has brought repercussions to them, such as lack of protection by the State, suffering, and school lateness (CNMH, 2013). They have lived threeforced displacements (Excerpt 3) which may explain why these students displayed misbehaviors accompanied by verbal and nonverbal aggression among them (Excerpt 4).

Excerpt 3

There is another internal displacement in Bogotá they had also suffered, this would be the third displacement that many of them have had, which consisted in arriving at the “Favorita” neighborhood, which is closer to Augustinian Caballero neighborhood.

Excerpt 4

“…JR is indifferent to the teacher’s authority all time and she is rude in front of the teacher. In one of these classes, home teacher had to stop a fight and asked children to calm down because JR called one of her classmates “Son of” (Swear word) …”

Armed conflict effects were also evident in kids’ mixed behaviors and identity (to be explained throughout the second category). Cultural practices in these students’ communities were influenced by the dominant culture (Excerpt 5). Students showed these mixtures contained in their underground memories (Blair, 2011) through their games, as explained in the third category (Excerpt 6).

Excerpt 5

Children indicate that in Pereira they played with water and bathed up to five times a day. The children also charge their cheeks with water and wet the others.

Some of them have preferences towards the musical genres of Reggaeton and Champeta. (…) made suggestions about how the Emberá Wera should look (tattoos, miniskirts, etc.).

Excerpt 6

The most valuable spaces of the schools are the playgrounds in the break that is where they are among them (…) Emberá boys who were playing, and they were playing that the girls had the baby and that the other came to take the coins, and then one of them hid the coins inside the baby’s blankets. He would take the money and another one would come and take the money from the rent.

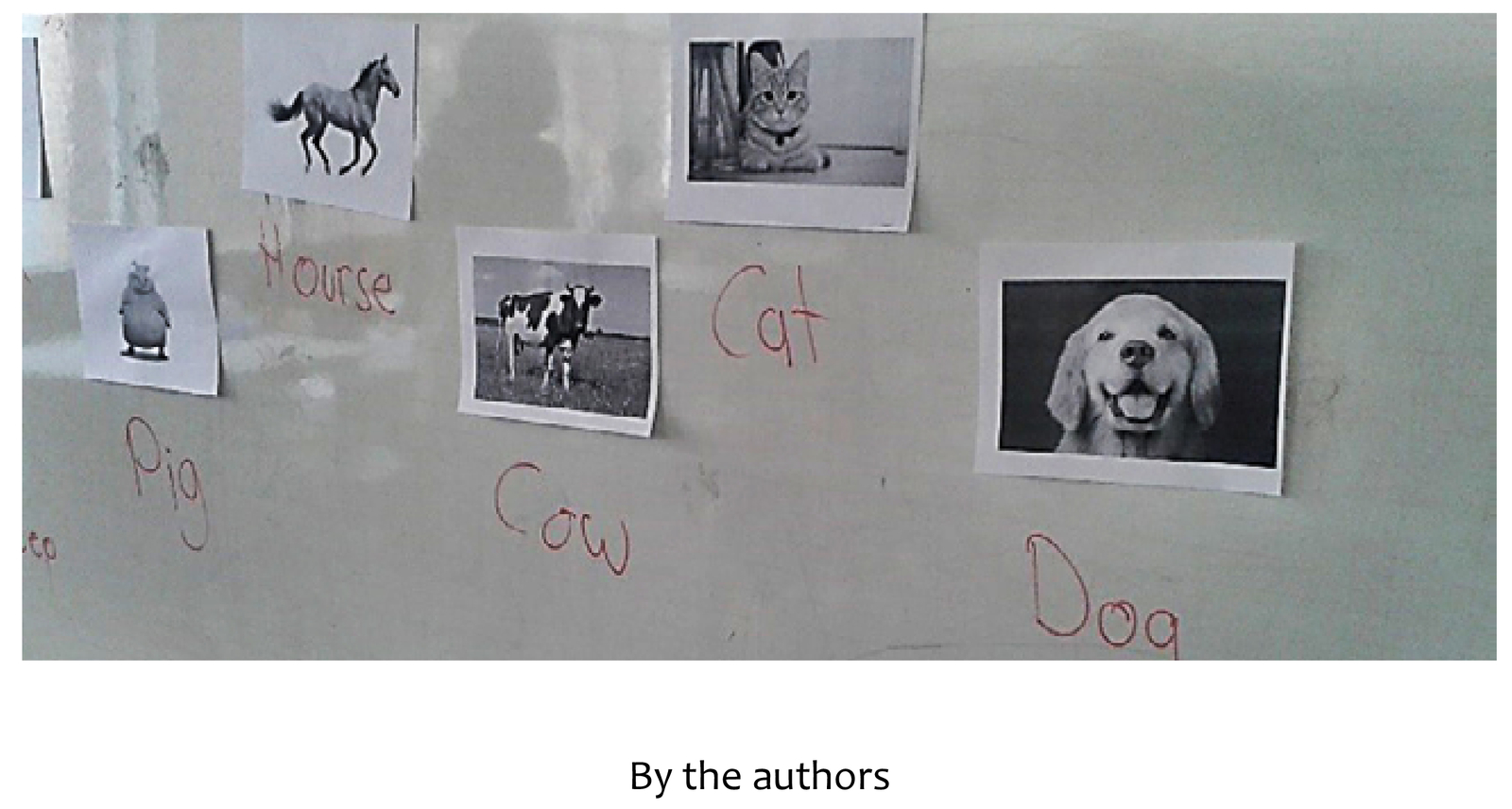

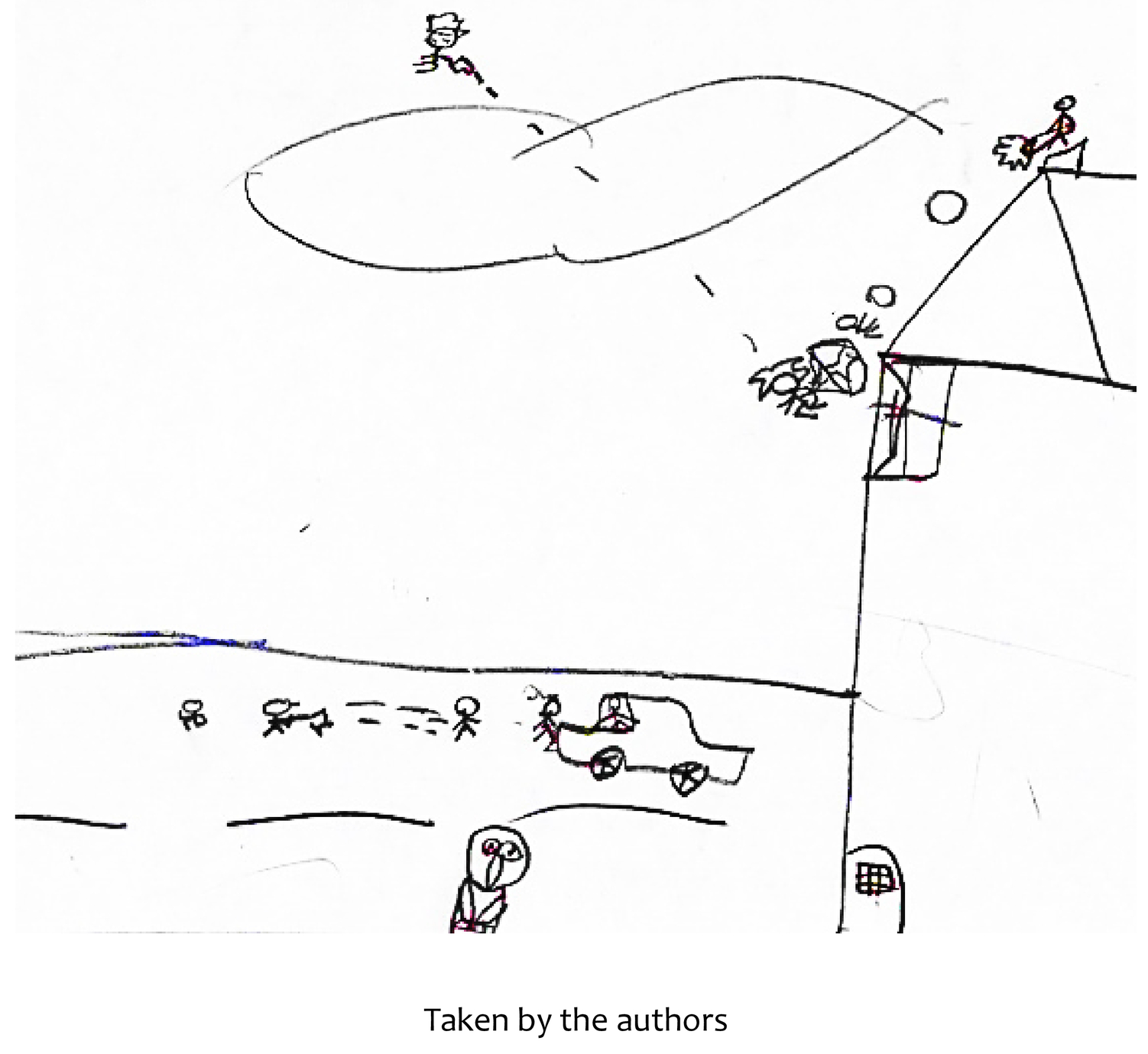

Students’ memory artifacts played the role of resources to rebuild students’ memories (Blair, 2011). Those artifacts were reconstructed by victim students through a didactic sequence in an ELF setting (Figure 2). Grounded on students’ memory artifacts, we interpreted multiple meanings on conflict-related phenomena coming from their experiences.

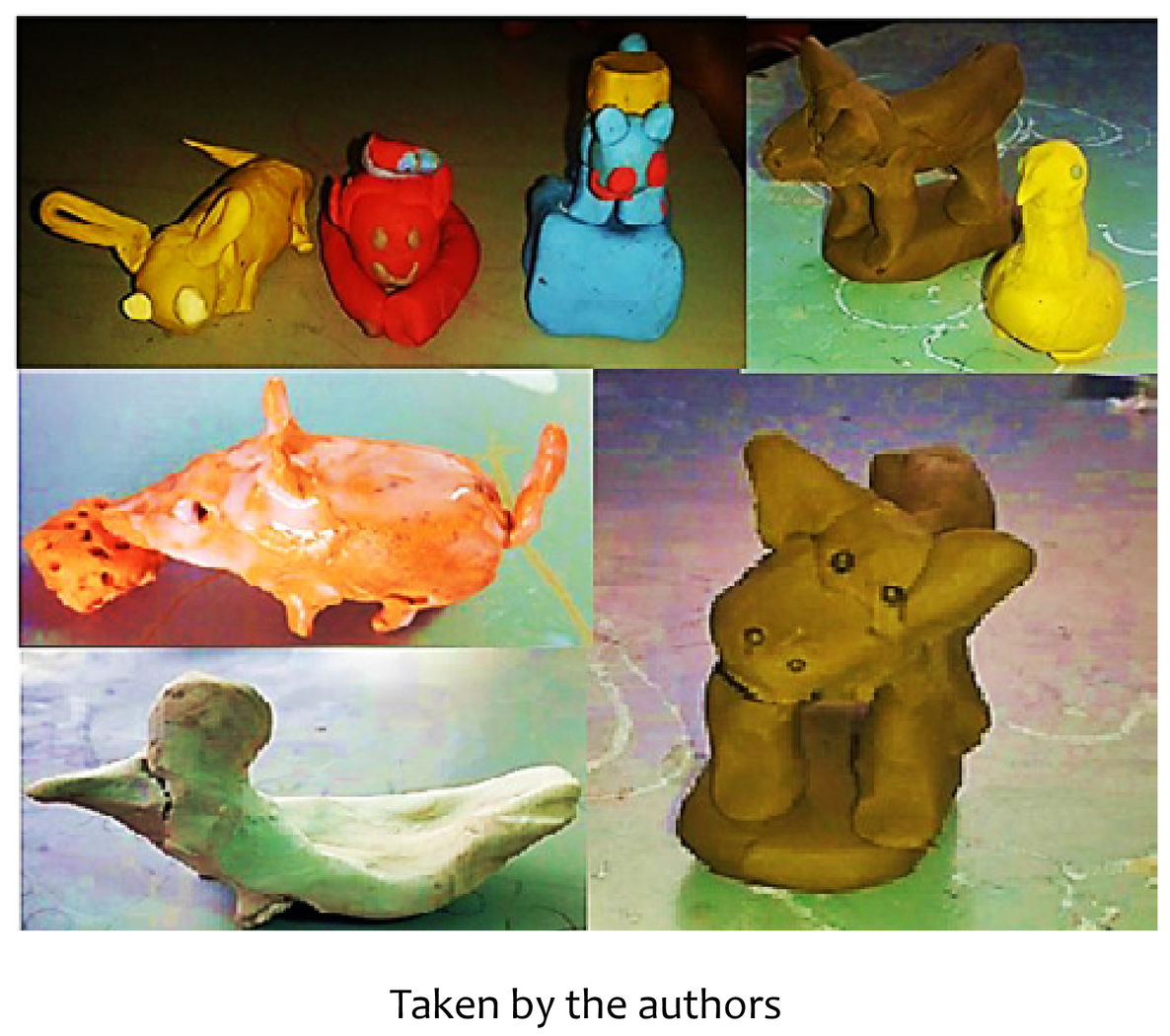

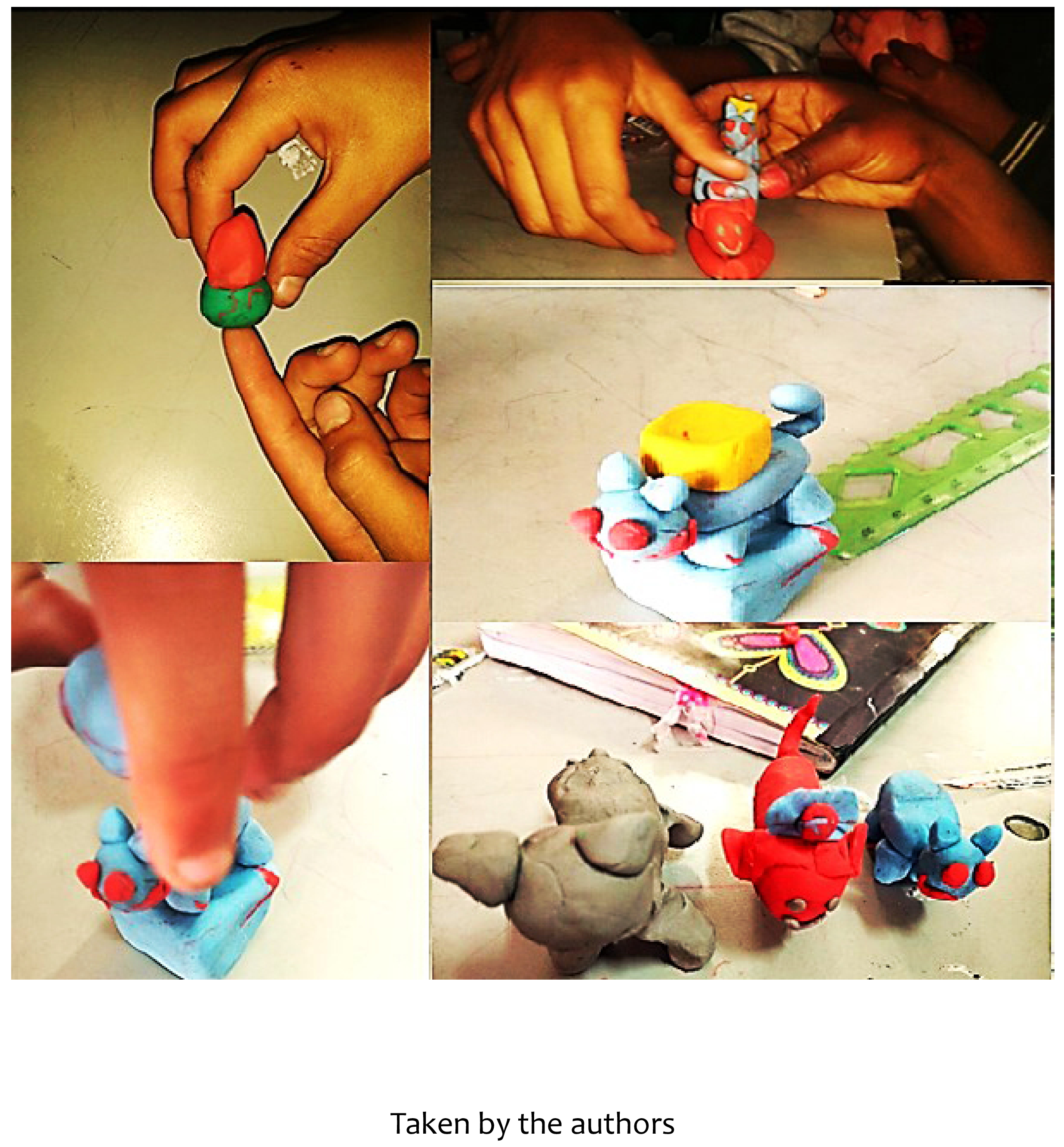

In one of the activities, kids utilized play dough for sculpting animals. Most of them were farm animals such as ducks, cows, and other mammals (Figure 3), despite living in urban settings now. This fact revealed students had a territory awareness concerning the place they lived before forced displacement and homes damage (CNMH, 2013). Likewise, students’ experiences materialized in memory artifacts (Blair, 2011) were resources for resilient processes through students’ dialogical conversations. As a tolerance and healing method of the Colombian conflict aftermath (Contreras & Chapetón, 2017), our didactic sequence facilitated a space for students to coexist and communicate about their town memories. Kids played with their artifacts that represented animals (figure 3). Students seemed to start friendship relationships by interacting differently in the game. Constructive interaction is necessary in the healing and reparation process. As Bhui, Silva, Harding and Stansfeld (2017) assert, friendships and support by family help victims to decrease distress and traumas.

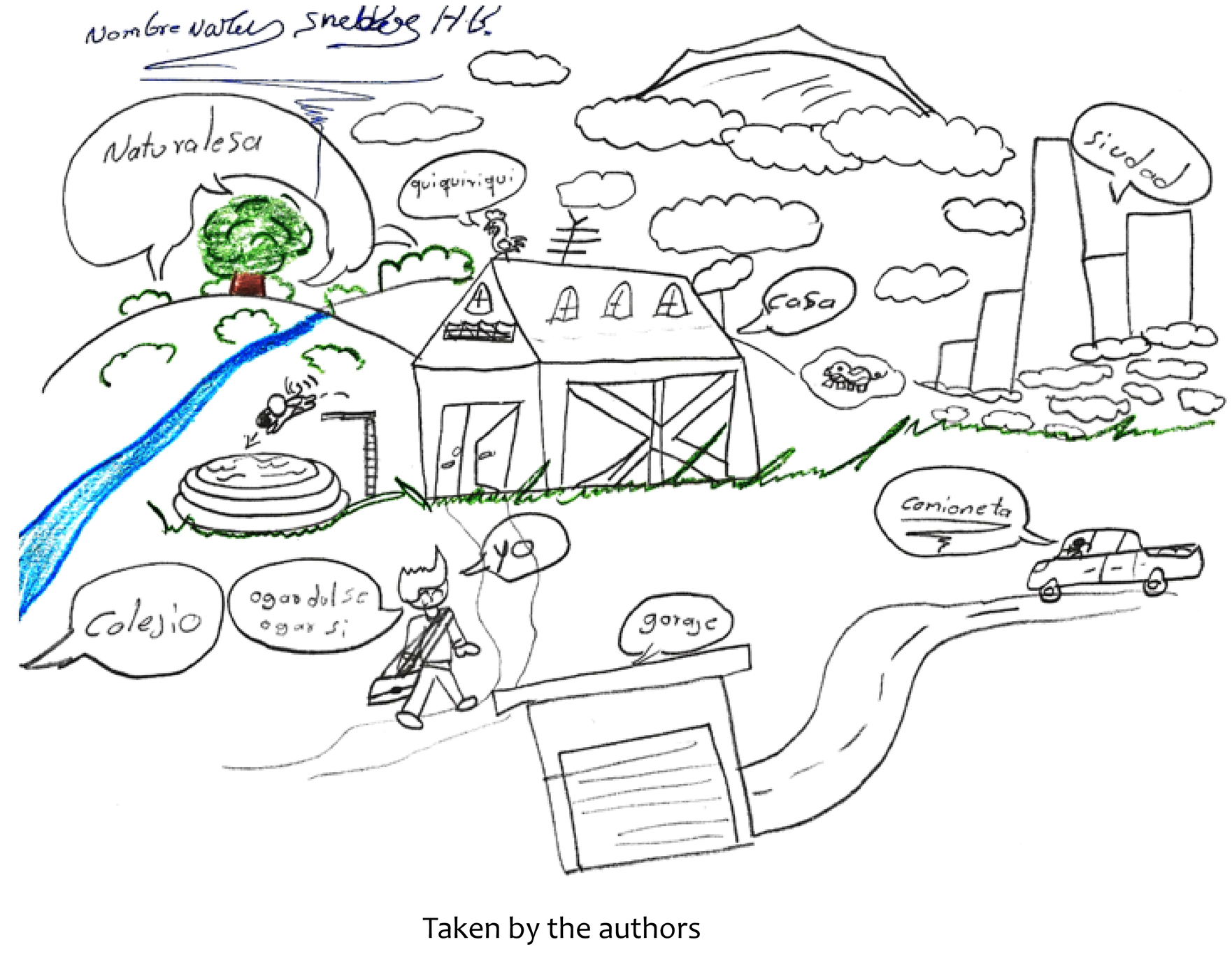

Similarly, another activity whose main topic was “home” emerged as an additional dialogical space where students had a further opportunity for healing. They drew their homes and displayed patterns about living places on paper. Firstly, most of the houses corresponded to farm sites which had characteristics such as animals, barns and rivers. Therefore, these indicators showed us that kids recognized the field or places outside the city as their home (figure 4). These artifacts placed students as victims of the armed conflict and especially affected by forced displacement (CNMH, 2013).

Victim students’ drawings (as in Figure 4) illustrate how forced displacement from hometown to capital cities (CNMH, 2013) was complemented by other similar conditions where they had to face inner displacement (Excerpt 3) and they were obliged to seek refuge. Figure 5 is an example of this, because one of the kids drew a church as his home and it could be interpreted as a refuge for him in the city.

Previous evidence portrays how victim- students activated their internal dialogue (Meijers, Lengelle, & Kopnina, 2016) through memory artifacts (Blair, 2011). Underground memories materialized through memory artifacts became an external dialogue (Meijers, Lengelle, & Kopnina, 2016), because they were visible and tangible to other people. Students’ voices could be understood not only as processes of healing, but as symbols of education for peace (Gustems, Calderón, & Calderón, 2017), since they have high levels of significance. As a result, traumatic events by the armed conflict might be stocked up in victims’ underground memories. Simultaneously, they were materialized through artifacts as resources of resilience that were elaborated while learners developed activities for their implicit recovery and repair process (Motti-Stefanidi, 2015).

In sum, student-victims in an EFL setting developed different memory artifacts which were full of meaning about their life experiences around the armed conflict. Some of them were related to their homes, lifestyle, pets, and forced displacement. Memory artifacts portrayed not only causes of student’s behavior, but they emerged as possible resources for peace education.

Fragmented identities in children of war

Colombian conflict sequalae along with transitional processes to post agreement scenarios may provoke fragmented identities in students who have experienced the role of victims. This means phenomena such as family dismembering or displacement may lead learners to re-signify their life experiences so that they can adapt to the new setting (Bottero, 2004). In the case of victims, conflict causes fragmentation in their daily lives within the community they live in (Bottero, 2004)

As an illustration of identity fragmentation, one of students in the EFL class expressed that a woman suffers because of her condition as a farmer (Excerpt 7). Interestingly, this answer is provided when the teacher as part of the dominant culture asks about students’ representation of an Embera wera (a woman). This shows how cultural identities meet and produce “conflicting tendencies and tensions” among students and the teacher, with diverse cultural backgrounds, and especially life experiences (Wodak, 2013, p. 143). This tension in the activity constituted an alternative to create a space of resilience for students as victims of conflict to exteriorize memories of suffering and reconstruct their identity in a class space (Motti-Stefanidi, 2015).

Excerpt 7

The girls draw a woman and represent her as a peasant. The teacher asks her why and she says that “they have suffered a lot because they are peasants”. On their billboard, using materials such as cloth, they draw the peasant woman in a long skirt and espadrilles.

Students in language classes may develop fragmented identities, inasmuch as languages are tied to cultural experiences (Bennett, 2013). Kramsch (2013) defines culture as either major symbols or everyday cultural practices. Victim students do not only develop fragmented identities for this particularity, but also as a result of their lived experiences in conflict and when facing dominant cultures. On the one hand, Embera students usually drew on their native language to talk to their partners and the teacher in the dominant culture. Thus, children enacted not only the dominant community language from where they currently are, but colonial languages and discourses around English within linguistic imperialism (Philipson, 2000).

On the other hand, identities from native and dominant language cultures were linked to territory notions too (figure 4). Student victims’ territory tie seemed visible through the displacement phenomenon. Students’ fragmented identities also combined armed and nonarmed situations in the resilience space from this class activity. Specifically, a student represented a violent event where a gunfight is taking place (figure 6). Association between home and a typical conflict taking place supports the idea that students exposed to warlike actions may be affected, having both direct and indirect consequences.

Learners with conflict background permanently articulated their local and external identities and demonstrated an interest in resilience (Motti-Stefanidi, 2015), founded on their perceptions and knowledge around otherness in different settings such as their native place and family history (Joniak-Lüthi, 2013). Identities then may depend on how we understand other people. In the present research, learners tended to use social labels from conflict to address and characterize their peers in their local fragmented identities. When students complained about others, they seemed to identify labels for pointing to others (Kalaga & Kubisz, 2008). In excerpt 8, the teacher underlines that students classify each other as chulo paraco. These social labels seemed to evidence conflict sequelae in victims’ identity fragmentation.

Students were aware of the crimes against humanity by some armed illegal groups; as a result, they identified themselves as such. Albeit children as victims of conflict associated armed illegal group labels to an insult, they included it in their fragmented identities. Besides, students used it as another social label to adjudge otherness (Kalaga & Kubisz, 2008). In excerpt 9, students deemed the teacher as a figure for them to refuse or reject peers’ actions, drawing on institutional norms.

Excerpt 8

When they’re treated badly, they say: “chulo paraco, chulo paraco”, I asked them what it was; “paraco, paraco kills, paraco is bad.”

Excerpt 9

It seems that students are accustomed to always having an authoritarian or regulatory body, either to control their actions or to find a shelter and be able to give complaints from another.

Nevertheless, Embera students’ fragmented identities also demonstrated they enacted institutional culture (Méndez, 2017). Our field notes referred to the fact that certain students did not wear their institutional uniform, but casual clothes from the dominant culture. Thus, another example of fragmented identities comes out as involving the tension between society and particular institutional regulations. In other terms, the notion of authority remains partial. Certain students did not even identify with the Embera leader’s demands, who was a supporter of children classes (field notes, Observation 2).

Children of the war found more tensions by the social labels and roles as victimizers and victims (Martínez, 2017). Usually, these students sought to bother others verbally and physically speaking. While observing the English class and playground, we recognized there were students identified with the role of victimizer when they decided to do something to establish their power relationships by imposing their control through violence cultural practices (Denov and MacLure, 2006). For instance, field notes in excerpt 10 narrate an event when a boy had an intimidating action towards a girl. This boy may not have had any reason or argument to do it, but he still did so with no regret. The girl identified with the victim who is afraid of and submitted to the victimizer. Gender identities in which inequality remains constitute critical phenomena usually reinforced by conflict (The transnational Institute, 2016). In sum, conflict violence practices have had an impact on children of war’s understanding of themselves and others, through rejection and low self-esteem (Nikolic-Ristanovic & Stevkovic, 2016). This can be repaired through resilience or collective reparation (Motti-Stefanidi, 2015).

Excerpt 10

One boy throws another girl’s jacket and says, “I can’t play with you because you’re a whiny.” When the girl picks up her jacket, the boy throws it back on the floor. She threatened to tell the coordinator, to which the boy replies that he has already been summoned. Then, he kicks the girl’s jacket and gives it three turns in the air, he throws it on the floor and he left.

Certainly, our participants as children of war seemed to display fragmented identities concerning sexuality. During activity explanations, children took some others’ papers in the role of victimizer and victims and drew penises on them. Most of the time, these actions suggest sexual violence in children of war’s background, according to the International Red Cross Committee (2011).

Excerpt 11

The students take away the sheets I gave to the others and I come over to find out why they do it. I realized that they were drawing male genital organs together.

Therefore, victims may feel affectivity-related needs within a fragmented identities framework. Children looked interested in or wanted affection plus expressions of it; however, they rejected it when other peers manifested those expressions of tenderness (Excerpt 12). Students wanted to receive love, but they struggled with this inner feeling, due to tensions caused between conflict memories and present situations, as Bar-Tal, Bieler, Boaz, Halperin and Porat (2014) also describe. Indeed, conflict sequelae in student victims involved affective personal instability which placed their setting and social contact at risk of victimization practices (excerpts 11 and 12).

Excerpt 12

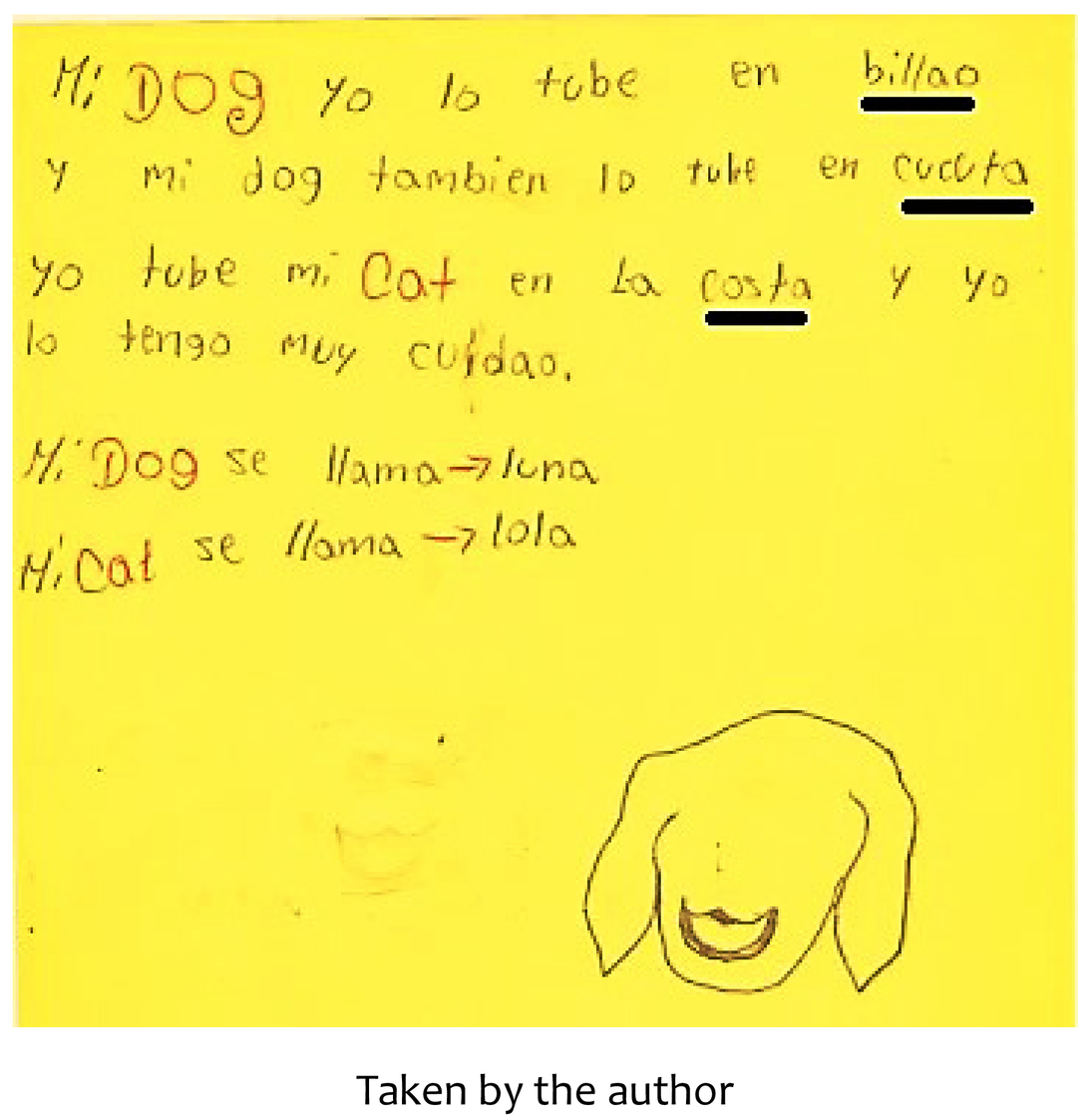

A student asks another: “What is your last name?”, then the same student says “a hug” and tries to hug the other. However, the other avoids it and makes gestures of throwing a fist… When analyzing victim students’ artifacts (drawings, play dough figures) and written narratives, one dimension in these participants’ identities deserves attention once again for its highly prominent presence in most learners’ artifacts. This characteristic refers to the connection between territory and displacement as constituting phenomena produced by conflict. In our students’ artifacts, they regularly communicated messages dealing with a myriad of places. In a student’s narrative (Figure 7), there were three different places connected. This fact may indicate constant mobility and displacement.

An additional example is figure 4 (in the first category) in which we have the representation of moving from the countryside to urban areas rather than the other way around. In this drawing, the child appeared in the countryside section through the label I (yo) and he drew only five buildings placed in the city area lifar away from him in the picture (figure 4). Cultural community distance (Aldana, Baquero, Rivero, 2012; Aldana, 2014) is suggested in this drawing, along with the student’s identification with the place of origin. His fragmented identity struggled with his dominant culture adaptation; he may miss the town left and resist to the new one. The Nature-territory-individuals as victims’ tie seemed strong and participated in identities construction (Leonard, 2017).

It is worth mentioning students’ fragmented identities intertwinement (Wodak, 2013) is as required as necessary for moving through different landscapes (Leonard, 2017). In this transition, victims of conflict as our students made decisions around their identities, founded on their conflict experiences in memories. As a result, identity change occurred when participants in this study created social labels or categories (Rumelili & Todd, 2017) for pointing to others (e.g. social, chulo paraco, loca). This very fact seemed to allow them to reproduce or enact dominant and institutional cultures through language when it was possible for them.

Albeit agency may depend on the degree of structure in a setting, it does not seem an illusion (Leonard, 2017). When participants gave meaning to conflict, they thought about humans’ actions in the conflict and they reclassified themselves by blending cultural practices. This is to say, students may embody their conflict experiences to necessarily practice their identities as part of their subjectivities in construction (Rebughini, 2014). We comprehended how participants in this study made political decisions on who they and others were in addition to what rights needed acknowledgement (Rebughini, 2014). In the observation within the library, students seemed to position towards marriage, expressing their resistance to it (field notes. Library).

In both cases, Embera students placed themselves as political subjects with rights. Indeed, Blake (2013) argues language can be considered as a right and resource more than a system. Embera students as victims of conflict constructed their subjectivities in agency, considering their fragmented identities and coding them through language. As there was a cultural and linguistic gap between students and the teacher, cultural disjunction appeared (Aldana, Baquero, Rivero, 2012) and intercultural communication was constrained.

Briefly, this category described children as victims of conflict, based on a set of experiences lived in different territories with armed conflict situations. These social and cultural circumstances seemed to have an impact on children identities, usually fragmented due to forced displacement and mobility. Gender, language, and ethnicity influenced by armed conflict represented our participants’ fragmented and paradoxical identities, coded through verbal and nonverbal languages. In didactic sequences towards peace education by Bottero (2004) it was found that social labels and classes served children to understand themselves, the surrounding world –usually different from their missed towns, otherness, and hopefully to feel empowered as agents of rights.

Conflict sequelae in game practices

This category discusses three wide viewpoints about student victims’ interactions that ensured a comprehension of these practices (Hunter et. al., 2011). Initially, verbal interactions in Embera students’ native and dominant languages were carried out to mediate meanings among them. Embera students tried to keep their cultural links in Spanish as a Second Language and EFL environment. As Lehmann-Willenbrock, Meyers, Kauffeld, Neininger and Henschel (2011) suggest, one of the primary modes of verbal interaction is mimic and each other’s oral statements to develop a sustained set of moods through an emotional spread. This may explain why students preferred contact with children from their culture in activities where they could use their mother tongue to interact and exchange feelings (Excerpt 13).

Excerpt 13

Embera students interact more with children from their own population with those who make work groups or friends to share during the break and workshops they carry out during class. They usually use their mother tongue.

Likewise, we observed an Embera native supporter speaker sometimes guided students’ behaviors towards the accomplishment of lesson tasks and students were responsive to his instructions (Excerpt 14). Nevertheless, students’ verbal and aggressive interaction returned not only as a response, but as a naturalized social practice (Excerpt 15). Lehmann-Willenbrock et al. (2011) understand an emotional extension as a support provided by a behavior. They affirm that if a negative or positive behavior remains, it will provoke a new task-related performance as we can appreciate in excerpt 15.

Excerpt 14

A man of indigenous descent acts as a support for the students, where he gives directions to the students in their mother tongue. Students stay focused for about 20 minutes…

Excerpt 15

Children refer to each other strongly and sometimes rudely, words such as “social, loca and chino” are used derogatorily to refer to each other.

The third viewpoint implied physical interaction among students. It held a deep connection with Lehmann-Willenbrock et al.’s (2011) emotional cycle. This one in turn pursued a pattern of double interaction (statement followed by response and a further statement) and where “complaining statements often occur in a complaining-support-complaining pattern. Humor manifests in cycles of humor-laughter-humor sequences” (Lehmann-Willenbrock et al., 2011, p. 644). Similar chains presented in participants’ game interaction, complemented by violent responses as imitation or extension of Colombian conflict sequelae. For instance, violent interaction patterns manifested in the cycles sequence: violent statement-physical response-physical violent reply (Excerpt 10). Another cycle occurred as physical violent interaction-physical violent response-non-verbal interaction (Excerpt 16). The second sentence in excerpt 10 exemplifies the first cycle in another violent interaction as a violent statement-response-physical violent reply pattern.

Excerpt 16

All the kids are crowded, there was a fight. One of the children pulled from the ear to another who had an earring. This caused bleeding. He decides to defend himself by punching the other in the face and makes him bleed too.

Excerpt 17

Others simulate expressions of violence such as beatings and fights. When they simulate fights, they use expressions such as “ñero, malparido” and other inappropriate expressions. Some children, when fighting, take the bag in their hand and roll it up in the same way as in armed hand fights.

Additionally, students also reflected violent interactions through their games that took place through punches and rough gestures, implying punishment. As Vitaro, Brendgen and Tremblay (2002) argue, most of the children that reproduce such actions are usually controlled by an aversive means that generates relationships with a lack of intimacy. As an example, Excerpt 12 and Excerpt 17 demonstrate that the lack of intimacy with the other facilitated an aggressive reaction as a first resource to respond to an interaction. Moreover, those coercive interactions increased vulnerability of students because of their learned practices, including communication ones, in conflict environments (Excerpt 17).

In students’ play, there were visible power relationships leading to violence. Students’ play was generally aggressive and annoying for the other. They strived to mark the position of dominance over a subjection. We could point to contexts of violence and displacement students have lived as a cause for children’s behavior that reflected survival instinct and strength in their games as living spaces. It deals with the analysis by Peter, Bowers, Binney and Cowie (2014) about relationships among children where the bullies (or victimizers) do not have a paternal model at home and have another family member in a first involvement rank. Children aggressiveness is an indicator of poor relationships with parents. Hence, victim students’ aggressive interactions deteriorated peer relationships (Excerpt 18) and influenced power relationships in their games. (Excerpt 6)

Excerpt 18

The teacher takes the students out of the room and makes them form lines while other students organize the room and two others sign a folder since they fought throwing objects, to the point that a teacher had to stop them.

Students’ games were based on role plays, in which, according to Moreno (2015), children take on the role of adults and this fact allowed them to recognize themselves through their participation in school activities. Interestingly, it involved rights along with duties, and it produced a nexus between children and peers that let them raise awareness about the meaning of their acts (Excerpt 6). Those mental processes may empower children to decide properly about their interactional patterns and roles in real context situations, while shaping students’ identity. Likewise, role play involved resilience processes where the students evoked memories about their previous experiences in the conflict and their territories (Excerpt 19). Those conflict experiences were manifested in children games in which they practiced and challenged their ability to identify their limits healthily, so as to overcome them through funny activities (Rodríguez, 2013).

Excerpt 19

Children are in the break time some of them play with water others play fighting, however, there does not seem to be any reason for it. Some children run because another student, who has the water, gets his/her classmates wet. The children indicate that in Pereira they played with water and bathed up to five times a day.

Therefore, the game involved students in the design, production and participation of a character in which they could express and project their own identities (Cortés Gómez, García Pernía, & Lacasa, 2012). On the collage of figure 8, we show students’ created pets in play dough. After creating them, students started playing with their own pets and others made by their classmates. Consequently, we observe that students projected themselves on their memory artifacts and played with them. They personalized their created pets during play time, drawing on their context they had already lived in past experiences. Thereby, teachers could maximize both active and creative learning.

As a conclusion, the data collection and analysis allowed us to understand students’ interactions. They displayed an evident pattern of violence in student’s practices through communication and role plays in games. When we analyzed and comprehended these students’ behaviors, we realized that most exchanges in games occurred aggressively, as victim learners unconsciously worked out to create resilient spaces that elicited peace. Game setting and practices seemed to afford the chance to evoke their memories and develop their identity. In a nutshell, students displayed interest in interacting differently with the otherness within environments which were geared to peace education.

Conclusions

With the aim of building education for peace, memory was a crucial resource for the recovery and possible reparation of students as victims of conflict within the EFL class. In this population, memory artifacts dealt with re-elaboration of conflict victims’ experiences. Situations manifested in memory artifacts pertained to their displacement from their towns to the urban settings and inside the city. Along these lines, students’ memory artifacts became supporting resources that allowed for resilience processes through didactic interventions and teachers’ support. Nowadays, memories are usually silenced and forgotten, i.e. those experiences do not have spaces to re-elaborate and manifest. This study opens up an alternative to welcome and construct dialogical places where student victims could have the opportunity to exchange and reflect upon their underground memories in EFL settings.

In this research study we were able to identify how student-victims denoted an explicit pattern of violence in their common practices related to their fragmented identities. Displacement and psychological sequalae from the conflict were the most evident contents communicated through these memory artifacts. Most of them were exteriorized as physical, verbal, and non-verbal interactions, which evoked their conflict lived experiences in playground games.

Moreover, traumatic events of the armed conflict were stocked up in the underground memory. These events were deposited and transformed in artifacts which may remain as a healing process of conflict sequelae and a resource in peace education to explore and include student victims’ identities.

In sum, we could assert that the most vulnerable victims of the Colombian armed conflict are children. Conflict sequelae seemed to come out through their interactional patterns with others. Therefore, we highlight the importance of the memory through artifacts as devices which open healthy spaces that contribute to peace education in the EFL class. Further research should focus its attention on the use of memories and their role in language classes for learners and teachers to participate in a collective reparation.