Innovative Learning Assessment in Secondary and Higher Education in Latin America: Systematic Review*

Gustavo A. Pherez

Faculty of Human Sciences and Education, Corporación Universitaria Adventista, Medellín, Colombia

https://orcid.org0000-0002-6515-0240

Nury N. Garzón

Faculty of Human Sciences and Education, Corporación Universitaria Adventista, Medellín, Colombia

https://orcid.org/0009-0009-1992-2009

Edna K. Conde

Faculty of Human Sciences and Education, Corporación Universitaria Adventista, Medellín, Colombia

https://orcid.org/0009-0009-1105-2651

Jorge Hoyos

Faculty of Human Sciences and Education, Corporación Universitaria Adventista, Medellín, Colombia

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7345-7867

ABSTRACT

Innovative learning assessment is considered a revolution to the traditional approach since it implies using contextualized tools and active student participation. While different research studies have addressed innovative learning assessment, there is a need to determine the strategies implemented. Therefore, through a systematic literature review, this article aims to identify innovative learning assessment strategies employed and reported in Latin American secondary and higher education institutions. An article search was conducted in databases, including Scopus, Scielo, Redalyc, Dialnet, Doaj, Realia, and Google Scholar. A total of 51 articles were identified and systematized following the indications of the PRISMA flowchart. A systematic literature review protocol was applied to screen articles from 2018 to 2023, with inclusion criteria focusing on studies conducted in Latin American contexts that address innovative assessment strategies at the secondary and higher education levels. This protocol facilitated the development of a source analysis matrix, with 19 articles retrieved for the present study. The analysis resulted in a categorization of the identified innovative assessment strategies based on their characteristics. The most commonly used strategies were those related to information and communication technologies, reported in 47.4% of the articles, followed by inquiry-based techniques in 36.8%, active methodologies in 26.3%, and, to a lesser extent, resource-based evaluation reported in 21.1% of the articles. Notable strategies include the use of memes, comics, portfolios, project-based learning, gamification, and co-evaluation. This review highlighted the authors’ common position on innovative assessment as a crucial element facilitating meaningful learning experiences, thereby transforming evaluation into a learning process.

KEYWORDS

learning assessment, innovative assessment, secondary education, higher education, Latin America

Evaluación innovadora de los aprendizajes en educación media y superior en América Latina: revisión sistemática

RESUMEN

La evaluación innovadora de los aprendizajes es considerada una revolución al enfoque tradicional, dado que implica el uso de instrumentos contextualizados y la participación activa del estudiante. Si bien diferentes investigaciones abordan la evaluación innovadora de los aprendizajes, se denota la necesidad de conocer las estrategias implementadas. Por tanto, este artículo pretende, mediante una revisión sistemática de la literatura, identificar estrategias de evaluación innovadora de los aprendizajes empleadas y reportadas en instituciones de educación media y superior latinoamericanas. Se realizó una búsqueda de artículos en las bases de datos Scopus, Scielo, Redalyc, Dialnet, Doaj, Realia y Google Scholar. Se consolidó un total de 51 artículos, los cuales se sistematizaron siguiendo las indicaciones del diagrama de flujo PRISMA adaptado. Para realizar el cribado se aplicó un protocolo de revisión sistemática de la literatura entre 2018 y 2023, considerando como criterios de inclusión estudios desarrollados en contextos latinoamericanos que dan cuenta de estrategias innovadoras de evaluación en los niveles de educación media y superior. Este protocolo facilitó el desarrollo de una matriz de análisis de fuentes con diecinueve artículos recuperados, con los cuales se realizó el presente estudio. El análisis arrojó una categorización de las estrategias de evaluación innovadora encontradas, de acuerdo con las características que presentan. Se determinó que las estrategias más utilizadas son aquellas relacionadas con las tecnologías de la información y las comunicaciones reportadas en el 47,4% de los artículos, seguidas por el uso de las técnicas indagatorias reportadas en el 36,8%, metodologías activas en el 26,3% y, en menor medida, la evaluación mediante entrega de recursos, reportada en el 21,1% de los artículos. Entre estas se destacan el meme, el cómic, el portafolio, el aprendizaje basado en proyectos, la ludificación (gamificación) y la coevaluación. Esta revisión evidenció la postura común de los autores acerca de la evaluación innovadora como un elemento fundamental que facilita la adquisición de experiencias significativas y hace de la evaluación un proceso de aprendizaje.

PALABRAS CLAVE

evaluación de los aprendizajes, evaluación innovadora, educación media, educación superior, Latinoamérica.

Avaliação Inovadora da Aprendizagem no Ensino Médio e Superior na América Latina: Revisão Sistemática

RESUMO

A avaliação inovadora da aprendizagem é considerada uma revolução em relação à abordagem tradicional, uma vez que implica o uso de instrumentos contextualizados e a participação ativa do estudante. Embora diferentes pesquisas abordem a avaliação inovadora da aprendizagem, há a necessidade de conhecer as estratégias implementadas. Portanto, este artigo pretende, por meio de uma revisão sistemática da literatura, identificar estratégias de avaliação inovadora da aprendizagem utilizadas e relatadas em instituições de ensino médio e superior na América Latina. Foi realizada uma busca por artigos nas bases de dados: Scopus, Scielo, Redalyc, Dialnet, Doaj, Realia e Google Scholar. Um total de 51 artigos foram consolidados e sistematizados seguindo as diretrizes do diagrama de fluxo PRISMA adaptado. Para a triagem, foi aplicado um protocolo de revisão sistemática da literatura nos anos de 2018 a 2023, considerando como critérios de inclusão estudos realizados em contextos latino-americanos que abordam estratégias inovadoras de avaliação nos níveis de ensino médio e superior. Esse protocolo facilitou o desenvolvimento de uma matriz de análise de fontes com 19 artigos recuperados, com os quais o presente estudo foi conduzido. A análise resultou na categorização das estratégias de avaliação inovadora encontradas, de acordo com suas características. Constatou-se que as estratégias mais utilizadas estão relacionadas às Tecnologias da Informação e Comunicação, mencionadas em 47,4% dos artigos, seguidas pelo uso de técnicas investigativas, relatadas em 36,8%, metodologias ativas em 26,3% e, em menor medida, a avaliação por meio da entrega de recursos, relatada em 21,1% dos artigos. Entre essas estratégias, destacam-se o meme, a história em quadrinhos, a carteira de trabalho, a aprendizagem baseada em projetos, a gamificação e a coavaliação. Essa revisão evidenciou a visão comum dos autores sobre a avaliação inovadora como um elemento fundamental que facilita a aquisição de experiências significativas e torna a avaliação um processo de aprendizado.

PALAVRAS-CHAVE

avaliação da aprendizagem, avaliação inovadora, ensino médio, ensino superior, América Latina

Introduction

Innovative learning assessment is a structured process that leads to improvement in teaching and learning and constitutes a necessity in today’s educational environment to respond to the challenges of the knowledge and information society.

Innovative learning assessment has been considered a revolution to the traditionalist approach to evaluation (Valverde, 2017). In this, the measurement of learning and results is considered more relevant than the process (Romero et al., 2018). According to Valverde (2017), traditional evaluation has mainly been based on exams and written tests. For its part, innovative learning assessment is characterized by allowing the active participation of students, being qualitative, transcending numerical measurement, and considering an ampler range of variables. Innovative assessment techniques, instruments, or tools differ from exams and include graphic organizers, presentations or oral defense, the elaboration of posters, and the execution of projects or games.

According to Valverde (2017), just as teaching and learning have changed, so must assessment since it must keep pace with the transformations occuring in cultural and educational contexts. This has been evident in recent years, as there has been an increased interest in developing innovative learning assessment strategies in Latin America. As a result, several researchers have compiled and reported a variety of novel and effective strategies for assessing student learning. Maureira-Cabrera et al. (2020) consider that co-assessment and self-assessment are formative assessments, given that they allow the role of evaluator, usually delegated to the teacher, to be assigned to students, enriching their knowledge and facilitating skills development. For their part, Zhinín et al. (2021) argue that assessment represents the means how students can become agents of change, innovation, and projection since it allows identifying the what, how, why, and when to do things to meet the proposed goals, not seeking as the principal and only objective to meet the exam requirements. This agrees with Castillo and Cabrerizo (2010), who mention this type of evaluation as an alternative model where the role of participants in the educational process is emphasized. A similar current is the one considered learning-oriented evaluation, the implementation of which seeks improvement in learning acquisition and, for this purpose, contemplates the active participation of students and the permanence of the evaluation, accompanied by feedback; as evaluation instruments, it considers those that favor the development of skills, competencies, and attitudes toward professional practice. In this line, it is worth mentioning authentic evaluation that also seeks innovation in assessment strategies by pointing out the incorporation of instruments or tools rarely used for evaluative purposes (Gárgano, 2020).

On the other hand, the study of learning assessment systems in Latin America conducted by the Working Group on Assessment and Standards of the Program for the Promotion of Educational Reform in Latin America and the Caribbean (Esquivel et al., 2006) presents assessment strategies to measure the quality of education at the state level, evidencing a strong focus on standardized tests. For his part, Fernández Santos (2019) offers interesting reflections on the need to transform evaluation and proposes some contextualized evaluative strategies; however, he does not record the implementation of these strategies in the teaching exercise. At the same time, Gárgano (2020) emphasizes the need to incorporate into education innovative assessment strategies that promote “understanding, the development of competencies, and the deployment of cognitive skills” to ensure that “learning lasts over time” (p. 204). Among the studies that identify and analyze evaluation strategies used in Latin America, the one conducted by Stieg et al. (2022) stands out. When contrasting the volume of publications related to assessment practices in physical education in Latin America and Spain, they highlight “as a worrying fact the lack of studies involving evaluative practices in physical education classes in the context of primary and secondary education in other countries, especially in Latin America” (p. 810).

The studies mentioned above, together with the article search, reveal a scarcity of research on the topic in question and a lack of compilation and analysis of innovative assessment strategies implemented at the secondary and higher education levels in Latin American institutions. In this study, according to the International Standard Classification of Education, secondary education is defined as second-grade education, and higher education as third-grade education (Taccari, 2009). Hence arises the need to identify, compile, analyze, and apply innovative assessment strategies that use techniques and instruments according to each environment.

Consequently, the study aims to identify innovative learning assessment strategies, techniques, or instruments used and reported in Latin American secondary and higher education institutions, as well as to provide a compilation of alternative learning assessment instruments or methods and the benefits that the application of these strategies brings to education, seeking to facilitate their consultation by teachers who wish to be part of the transformation of educational processes and contribute to improving the quality of education.

Method

This study employed a qualitative research methodology based on a literature review. In this research, literature review is understood as “looking back at what has already been written on a certain topic to inform and develop practice and invite discussion in academic work” (Guirao, 2015, p. 2), taking as a basis the model proposed by Guirao-Goris et al. (2008), which consists of four phases: a) definition of the review objectives; b) bibliographic search in databases and documentary sources, establishing a search strategy and specifying the inclusion and exclusion criteria for articles; c) organization of the information; and d) writing of the article.

This review aimed to identify innovative learning assessment strategies, techniques, or tools used and reported in Latin American secondary and higher education institutions. The questions that guided the review were the following: What assessment techniques, instruments, or tools are considered innovative? What innovative learning assessment strategies are implemented in Latin American secondary and higher education institutions? And what are the advantages of using innovative learning assessment strategies?

For the analysis of the selected studies, the area or subject in which innovative assessment strategies were used was not considered relevant.

The bibliographic search was based on an information review protocol, as presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Information review protocol

|

Academic databases |

Keywords |

Inclusion criteria |

Exclusion criteria |

|

Scopus SciELO Redalyc Dialnet DOAJ Realia Google Scholar |

Learning assessment Innovative strategies Innovation in assessment Secondary education Higher education |

Publications and research that refer to innovative learning assessment strategies. Studies conducted in secondary and higher education. Place of application: Latin America. Articles in academic databases. Published between 2018 and 2023. Articles available in databases and in full text. |

Publications that refer to the implementation of traditional evaluation strategies. Publications in non-educational contexts. Publications of cases in non-Latin American contexts. Publications that do not correspond to secondary or higher education levels. |

Table 2 presents the search strategies used in different databases.

Table 2. Descriptors used in the relevant literature search process

|

Database |

Descriptors |

|

Scopus |

TITLE-ABS-KEY (“estrategia” AND “evaluación” AND “innovadora”) (“evaluación” AND “Educación media” OR “Educación secundaria”) (“evaluación” AND “Educación Superior”) |

|

SciELO |

(“estrategia” AND “evaluación” AND “innovadora”) (“estrategia” AND “evaluación” AND “innovadora” AND “aprendizaje”) |

|

Redalyc |

(“estrategia” AND “evaluación innovadora” AND “aprendizaje”) |

|

Dialnet |

(“estrategia” AND “evaluación” AND “innovadora” AND “aprendizaje”) |

|

DOAJ |

(“estrategia” AND “evaluación” AND “innovadora” AND “aprendizaje”) |

|

Realia |

(“estrategia” AND “evaluación” AND “innovadora” AND “aprendizaje”) |

|

Google Scholar |

(“Estrategias” AND “evaluación innovadora” AND “Educación media” AND “Latinoamérica”) (“Estrategias” AND “evaluación innovadora” AND “Educación superior” AND “Latinoamérica”) |

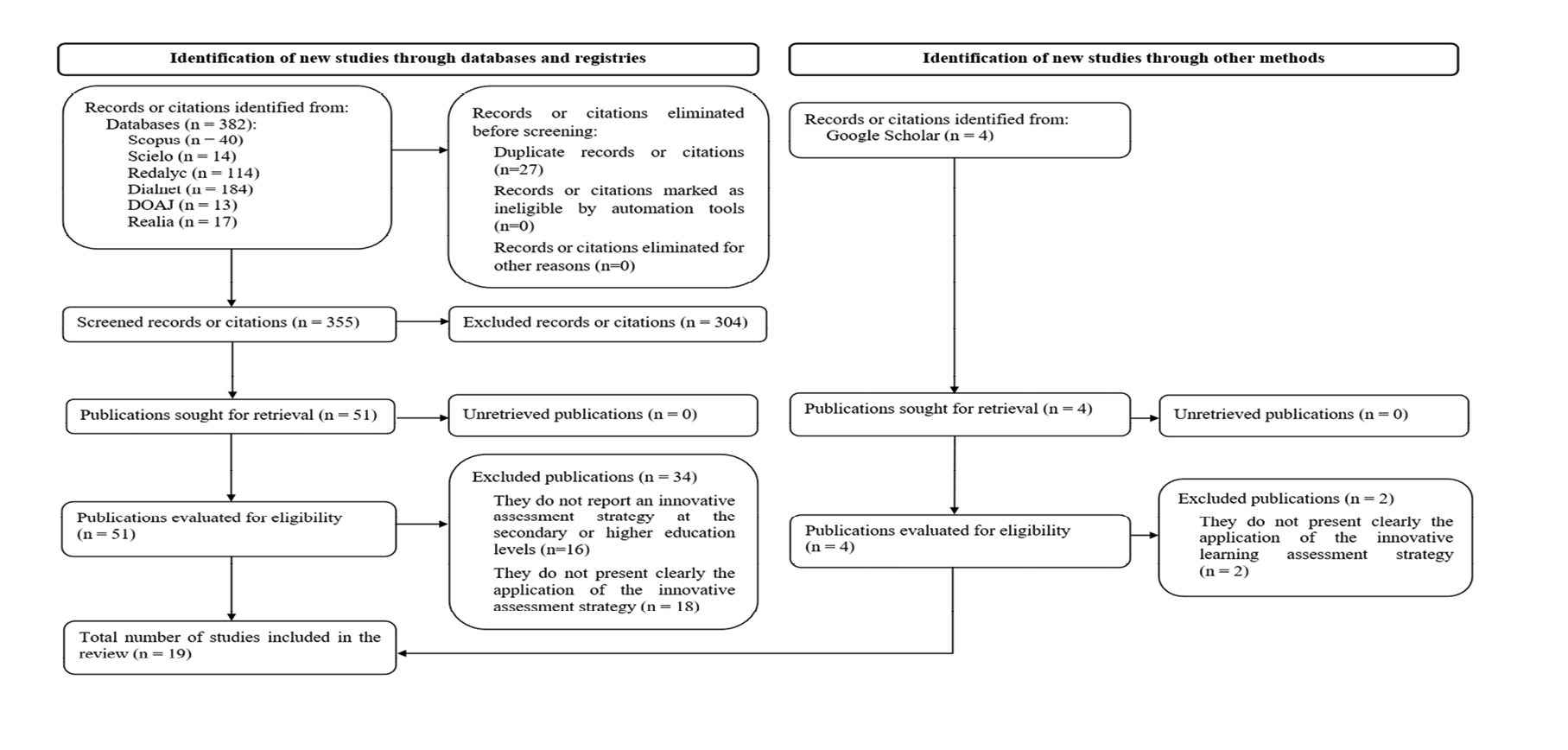

Figure 1 details the article selection process from identification to the screening phase. The search in the previously mentioned databases generated 382 studies, of which 27 were eliminated since they were duplicates. After reading the title, abstract, and keywords, it became evident that some of these investigations were incompatible with this review; therefore, 304 articles were excluded, resulting in a group of 51 documents in three languages: Spanish, English, and Portuguese. The selection process followed the indications of the PRISMA flowchart adapted from Page et al. (2021).

Figure 1. Article selection process

Note: Own elaboration based on the translation of Yepes-Núñez et al. (2021).

For the documentary review, a source analysis matrix was consolidated that considered the articles according to the model proposed by Caro et al. (2005), which describes each article with their respective Title, Author(s), Year, Category or Descriptor, Database, Type of document, Language, Approach, Relevance of content, Selection by criteria, Methodology, Results and/or Article development, Discussion and/or Conclusions, and Access link.

The information review process was guided by the following review standards, adapted from Caro et al. (2005):

- Diagnosis of the existence of analogous or nearby works on the object of study.

- Review of the sources of information, taking the research horizon (problem and objectives) as a constant reference for revision.

- Retrieval of complete works, verifying their relevance for the research.

- Preliminary reading of the abstract and introduction as an inclusion or exclusion strategy.

- Comments about the study (relevance, highlights, or other aspects).

- If the source is selected by inclusion and exclusion criteria, continuation of reading and analysis of the remaining sections; otherwise, inspection of the next source.

Finally, 19 studies presenting innovative learning assessment strategies were selected. The selection of documents relevant to this study was based on the following inclusion criteria: articles in databases with a publication date between 2018 and 2023, available in full text, referring to the implementation of innovative learning assessment strategies at the secondary and/or higher education levels in Latin American countries.

Publications related to initial and basic education were excluded, as well as those that, despite referring to innovative learning assessment instruments, did not correspond to Latin American contexts, were not related to learning assessment, or examined assessment tools considered traditional.

In addition to screening by exclusion criteria, a new selection was conducted based on the review of the methodology and, in some cases, the results, excluding those articles that did not describe in a detailed or clear manner the assessment strategy or its application and/or did not present the results of its implementation.

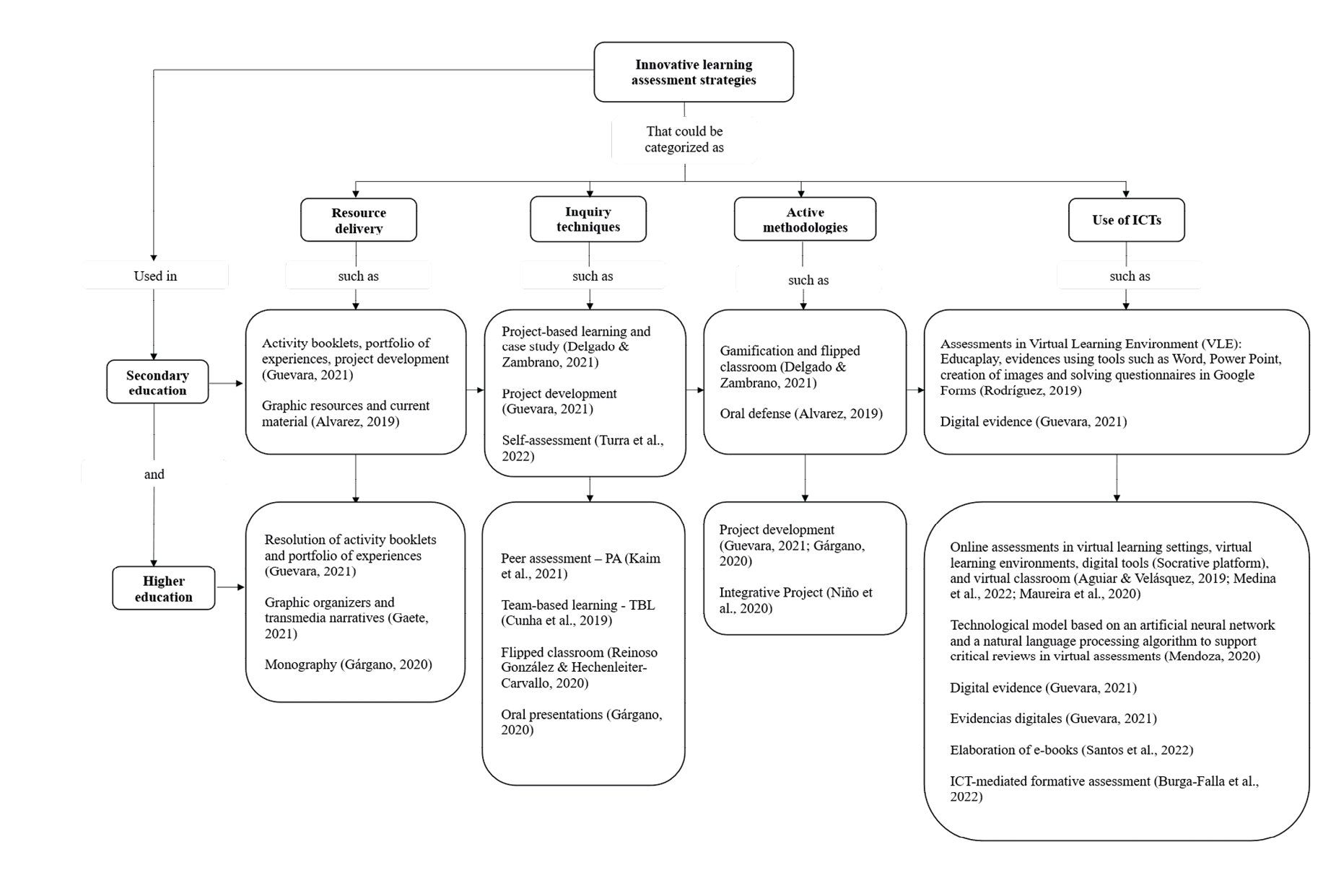

After completing this process, the selected articles were classified by the educational level reported. Subsequently, the innovative assessment strategies found in the studies were grouped according to their characteristics: a) resource delivery, b) inquiry techniques, c) active methodologies, and d) the use of information and communication technologies (ICTs).

Results

The final sample of 19 articles on the application of innovative learning assessment consisted of 14 articles corresponding to the higher education level and 6 articles corresponding to secondary education; this summed up to 20 since one of the selected studies dealt with both educational levels. Table 3 presents a percentage analysis of the strategies reported in the analyzed articles.

The results show that the most frequently used methods were those mediated by ICT, reported in 47.4% of the articles, followed by inquiry techniques, reported in 36.8%, and the use of active methodologies in 26.3%. Finally, resource delivery was employed in 21.1% of the articles.

Table 3. Percentage of application of innovative assessment strategies

|

Type of innovative assessment strategy |

Percentage of reporting within the total selected articles |

Percentage of reporting, by educational level |

|

Resource delivery |

21.1% |

Secondary education: 25% Higher education: 50% Both levels: 25% |

|

Inquiry techniques |

36.8% |

Secondary education: 42.9% Higher education: 57.1% |

|

Active methodologies |

26.3% |

Secondary education: 40% Higher education: 60% |

|

Use of ICT |

47.4% |

Secondary education: 11.1% Higher education: 77.8% Both levels: 11.1% |

The results show that the most frequently used methods were those mediated by ICT, reported in 47.4% of the articles, followed by inquiry techniques, reported in 36.8%, and the use of active methodologies in 26.3%. Finally, resource delivery was employed in 21.1% of the articles.

Next, we will describe the innovative learning assessment strategies implemented in secondary and higher education and detail the benefits reported by the authors after applying them. Finally, we will present a synthesizing scheme that specifies the strategies implemented, grouped according to their characteristics, and classified according to the educational level.

Innovative learning assessment strategies

Figure 2 groups different assessment techniques categorized as innovative, which coincides with Carbonell (2002), who considers innovation to be interventions, decisions, and processes with a certain degree of intentionality and systematization that seek change in pedagogical practices, which, of course, involves learning assessment. The findings are analyzed below, specifying the instruments and characteristics of each strategy.

- Resource delivery

The delivery of activity folders or notebooks, as well as graphic organizers for later review, is considered innovative since it moves away from evaluation stereotypes. For analysis, they have been grouped under the title Resource delivery in this article, given that they constitute tangible evidence produced by the students.

Among the studies, Alvarez’s (2019) proposal stands out for different aspects, such as evaluation time, use of creativity, and oral defense. The author asked her students to search for graphic material from magazines, newspapers, and other current sources related to the topic to be evaluated before the assessment. This material served as input for the elaboration of a collage to which the students added some texts related to the concepts seen in the area of social sciences in secondary education to explain orally, in front of the class, the acquired learning.

On the other hand, Guevara (2021) reports the use of instruments such as checklists and the delivery of workbooks and textbooks sent to teachers as photographic evidence during virtual class time due to the COVID-19 contingency. These were graded under criteria such as quantity/content and accuracy of the evidence presented and, in some cases, averaged together with exams, questionnaire resolution, or essay writing.

Meanwhile, at the higher education level, a strategy proposed by Gaete (2021) stands out, which uses non-linguistic graphic organizers for evaluation purposes, including mind maps, comics, and memes. For assessment, a rubric was shared with the students, describing the aspects considered unsatisfactory and satisfactory for qualification. The products were elaborated in teams of four and then sent by e-mail within a previously agreed deadline to be presented orally before the teacher. To consider these graphic organizers as innovative assessment tools, the author surveyed his students on the activity, who highlighted the comic as the best method to consolidate learning results. Finally, the use of this strategy is mentioned by Gárgano (2020), who considers class work linked to common discussions (inquiry techniques) as the most effective assessment strategy, voted by 31.7% of the students, followed by the submission of individual monographs with 17.5% of votes.

Figure 2. Innovative assessment strategies reported and classified according to their

characteristics and the educational level

- Inquiry techniques

Inquiry techniques have been categorized as innovative assessment strategies, given that they facilitate autonomous learning directed by the guidance and tutoring of teachers during the process (Tobón et al., 2010).

Case studies, team-based and project-based learning, and the flipped classroom have been found in studies on secondary education. When using project-based learning and case studies, Delgado and Zambrano (2021) associate them with the use of rubrics, reports, and written tests. At the same educational level, Guevara (2021) reports the elaboration of an educational intervention project as part of the final evaluation of a course. This strategy was developed in the context of the COVID-19 contingency in Mexico, where teachers were told that they were free to create the most appropriate response to continue with the teaching-learning and evaluation process. As an inquiry technique, Turra et al. (2022) indicate that self-assessment was innovative for students since it allowed them to take control and evaluate their performance.

Similarly, at the higher education level, Kaim et al. (2021) describe the use of peer evaluation (co-evaluation), together with the design of a rubric and the accompaniment of teachers, for the analysis and critical qualification of posters that demonstrate the acquired learning. This is relevant when considering assessment as a learning opportunity.

Linked to this is the technique proposed by Cunha et al. (2019), which integrates project-based learning with team-based learning through the preparation and defense of coursework supported by posters about selected contents based on experiences in field practice (in medicine) and their presentation in portfolios. This strategy is similar to the one used by Gárgano (2020), who refers to the active participation of students in common discussions as the most effective strategy used, in addition to oral expositions—although less valued.

Finally, a “multiple-choice group test using the Kahoot digital platform” should be highlighted, which was designed by Reinoso-González and Hechenleiter-Carvallo (2020), who considered averaging the results of this test with the results obtained in a diagnostic evaluation and proposed to reflect on the impact on students using the perception scale of the module with methodological innovation (EPMIM, for its initials in Spanish).

- Active methodologies

According to Gordón et al. (2021), active methodologies involve the participation of students as protagonists.

At the secondary education level, these include gamification—which in turn involves playfulness and games—and the flipped classroom; at the higher education level are the elaboration, formulation, design, development, and evaluation of projects and the integrative project.

Delgado and Zambrano (2021) report gamification as a learning tool that involves games in the educational area, which was applied to “the students of the Second Baccalaureate of the Veintitrés de Octubre Educational Unit” (p. 52) by 27% of the teachers, as well as the flipped classroom, cataloged as a useful tool that substitutes conventional classes and that “covers all phases of the learning cycle” (p. 58): a) knowledge, b) comprehension, c) application, d) analysis, e) synthesis, and f) evaluation (Casanova, 1995).

For her part, Alvarez (2019) reports the use of collage and oral defense, where students were required to dialogue with their families to prepare their defense.

Regarding project-related aspects, the experience of applying integrative projects stands out, which is a curricular integration strategy also used in assessment that “allows the development of competencies from several disciplines and integrative themes to acquire real experiences with a continuous, qualitative, and integrating evaluation” (Niño et al., 2020, p. 3). Likewise, as evidenced in Gárgano (2020), it is worth highlighting the perception of students about implementing projects as an assessment strategy, who valued it positively.

- ICT-mediated assessment

Finally, ICT-mediated assessment strategies have the highest percentage of reports in the selected articles.

At the secondary education level, activities and evidence using digital tools are reported as innovative assessment techniques.

Rodriguez (2019) indicates the implementation of a virtual learning environment (VLE) designed on the e-learning technology platform using free software Chamilo for academic media in visual arts in a school, with evaluative activities of presentations, written answers, crossword puzzles, timelines, concept maps, and portfolios developed through virtual tools such as Padlet, Canva, Lucidpress, Piktochart, Emaze, MovieMaker, among others. For his part, Guevara (2021) reports the use of digital evidence as an assessment method due to the pandemic situation, while the research conducted by Turra et al. (2022) describes a collaborative culture directly related to technological culture in the evaluative field. Burga-Falla et al. (2022), for their part, present the implementation of formative assessments, including co-assessment and self-assessment, in the post-pandemic era using digital tools.

In higher education, assessments are reported in virtual learning settings and VLEs on platforms such as Socrative and the Virtual Classroom.

Aguiar and Velázquez (2018) present a proposal for the future implementation of assessment in VLEs in medicine at the Universidad Católica de Santiago de Guayaquil, given the positive results they have evidenced in the literature.

Mendoza et al. (2021) report in their study the case of the Universidad Pedagógica y Tecnológica de Colombia, which applies the following methods to evaluate virtual learning:

a) Development of workshops, questionnaires, and online evaluations, participation in forums and chat, laboratory and field practices in 36%; b) Project-based evaluation, competencies, and reflective evaluation in 25%; c) Laboratory and field practices in 11%; and d) Practical projects and online evaluation, use of technological tools, continuous and constant communication measuring scales of participation in 28%. (p. 387)

These practices employed self-evaluation and co-evaluation in 29%, diagnostic, continuous, and summative evaluation in 35%, and formative evaluation in 36%.

For their part, Medina et al. (2022) propose the use of the Socrative platform, a free online tool to design questionnaires under the true/false, multiple response, and short answer modalities. This strategy is reported as a summative assessment.

Another way of using technology is to support the review process of virtual assessments. In this sense, Mendoza (2020) implemented “a technological model based on an Artificial Neural Network and a Natural Language Processing algorithm” (p. 26) to automatically process “critical reviews in virtual assessments of undergraduate students” (p. 26) on the Moodle virtual platform. The author indicates that “in the results of 15 learning stages, accuracy was 94.4%” (p. 34).

Another technique employed was virtual portfolio, reported by Fosado et al. (2018). The authors describe the design of an electronic portfolio as an instrument to assess the acquired learning in the subject of Sustainable Development at the Universidad Autónoma de San Luis Potosí: “The portfolio was designed in the Wikispaces Classroom platform, with 15 activities and instructions for their completion” (Fosado et al., 2018, p. 201). It was applied in nine courses with a student participation of 95%.

Likewise, Mendoza et al. (2021) report the use of chats and forums, applied by 36% of 41 tutors selected for their study, while Santos et al. (2022) report the development of an e-book with previously established parameters as an assessment strategy during the COVID-19 contingency.

Advantages of the implementation of innovative learning assessment strategies

Innovative learning assessment strategies are mainly inscribed in pedagogical models affiliated with the constructivist model, in which assessment and learning seek the development of cognitive and affective skills, which involve the assimilation and appropriation of concepts, models, and practices, i.e., knowledge. The authors of the analyzed studies agree that the implementation of these innovative assessment techniques seeks meaningful learning; for Gordón et al. (2021), this is achieved by using ICT-mediated strategies. Table 4 summarizes the benefits of applying innovative learning assessment strategies mentioned in the studies.

Table 4. Benefits of implementing innovative learning assessment strategies

|

Innovative assessment strategy |

Benefits |

|

Resource delivery |

They facilitate understanding. They favor contextualization with reality. They encourage learning. They exert less pressure. |

|

Inquiry techniques |

They give prominence to students. They develop creativity. They encourage collaborative work. They generate motivation. They stimulate reading. They give control to students. |

|

Active methodologies |

They increase concentration. They improve logic. They simulate work environments. They enable agile work. They facilitate communication, language, and the way of expressing knowledge. |

|

Use of ICT |

They are playful and interactive. They contribute to comprehensive education. They promote interdisciplinarity. They facilitate teaching in times of crisis. They promote creativity. They favor the development of social skills. They improve the quality of teaching. They motivate learning. |

|

All of the above |

They improve attention. They are innovative, didactic, and interesting. |

As shown in Table 4, the benefits of applying innovative learning assessment strategies are common to several of the four categories presented. They are specified in more detail below.

Evidencing and exemplifying learning

Guevara (2021) reports that, after implementing strategies categorized as resource delivery, such as reviewing activity booklets, portfolio of experiences, and developing projects, students and guardians showed improvement in attention and considered that these activities promoted learning.

For her part, Alvarez (2019) indicates that the use of organizers or graphic resources (memes, mind maps, and comics) presented advantages in learning and understanding concepts and establishing relationships between ideas and situations, as well as in the interpretation and development of critical thinking when addressing problems and relating them to their experiences. This same study describes oral defense as an assessment strategy; students mentioned that such methodology contributed to developing their communicative skills when faced with the need to express opinions, concepts, and conclusions. Additionally, this type of evaluation generated “the possibility of researching and having fun, expressing oneself differently, feeling less pressured and calmer, learning about topics that are not taught in other subjects, and the realization of a more creative and free evaluation” (Alvarez, 2019, p. 158). It is worth noting that, according to the author, at the end of the term, students remembered the evaluated concepts and were able to “exemplify them and relate them to current events” (p. 159). Regarding the elaboration and delivery of monographs, students stated that this strategy stimulated reading (Gárgano, 2020).

To conclude, Gaete (2021) suggests that the implementation of graphic organizers or transmedia narratives (memes, mind maps, and comics) is an adequate alternative to strengthen formative assessment, taking into account “the learning styles of students, the competencies related to each subject, the graduation profile of each program, etc.” (Gaete, 2021, p. 402). The author emphasizes group work as an active methodology that gives a prominent role to students. The students cited by the author alluded to such strategies as entertaining and innovative that strengthen teamwork; at the same time, “the embarrassment to make a presentation correctly” (Gaete, 2021, p. 402) provoked greater excitement and time for its execution and helped develop creativity.

Active participation and generation of creative ideas

The research conducted by Delgado and Zambrano (2021) concludes that the use of “creative tools for assessment contributes to improving the teaching and learning process” (p. 60) and “to developing the process of generating creative ideas” (p. 60). An inquiry technique evaluated by Turra et al. (2022) is self-assessment, which, according to students, allowed them to take control of the process by judging their performance and making decisions to achieve the proposed objectives.

For Kaim et al. (2021), some benefits are improving the skills necessary for medical practice, such as teamwork, feedback, decision-making, conflict management, and the development of autonomy. Similarly, the strategy implemented by Cunha et al. (2019) was valued positively by students who considered that it resembled the “atmosphere of a congress” (Cunha et al., 2019) and allowed learning acquisition from the experiences of their peers and feedback from teachers and peers.

To close this section on the benefits of inquiry techniques, the findings of Gárgano (2020) should be highlighted, which indicate that students valued being able to explain their points of view through concrete questions and problems that linked the thematic content with practice. Similarly, after using Kahoot as an innovative learning assessment strategy, Reinoso-González and Hechenleiter-Carvallo (2020) record that the results of a perception survey showed satisfaction of 69% with this assessment strategy. When considering the best course aspect (between teaching methodology, planning, expectations, and assessment), assessment obtained the highest score (77%). The authors also report that this strategy allowed the active participation of students, facilitated the immediate delivery of results, strengthened feedback processes, and was well received by students; it was considered a strategy that improved motivation in the group.

Doing and learning with motivation

In the category of active methodologies, the findings demonstrate the following benefits: development of comprehension, increased motivation toward learning, increased attention and concentration level, optimization of academic performance, and improvement of logic and problem-solving strategies (Backhoff et al., 2007). Employing the flipped classroom also provides benefits. According to Backhoff et al. (2007), these consist of allowing “the teacher to perform other more individualized activities during class” (p. 58), enhance the collaborative environment, reinforce students’ motivation, and involve families in learning.

Active methodologies can be circumscribed in connectivism, a theory of knowledge that postulates that “we learn by making connections with other people, concepts, and ideas” (Solórzano & García, 2016, p. 99), which is evident in the previously mentioned benefits. It is also supported by Alvarez (2019), who reported oral defense as an innovative assessment technique, resulting in a different way of learning, evaluating, and working in the classroom. It was categorized by students as didactic and interesting, which allowed relating concepts using comprehension, interpretation, and expression, involving history, daily life, and experiences.

Niño et al. (2020) report that more than 90% of students considered that assessment through an integrative project allowed them to understand the relevance of teamwork, the roles and functions to be performed, and, in disciplinary topics, what corresponds to “the phases of the software life cycle, the principles and tools of project management, and agile practices” (p. 6). On the other hand, more than 90% of the students stated that this strategy gave merit to learning, favored the achievement of competencies, simulated work environments, and helped demonstrate the characteristics of teamwork. In addition, regarding soft skills or soft competencies, such as empathy, responsibility, honesty, respect, compliance, and perseverance, around 75% of the students considered that they had developed these competencies during the work performed. On the contrary, regarding the section on healthy habits, although over 80% of students reported that they know their importance, the frequency of practicing these habits was not evident. According to the authors, there was “little attention to visual health, ergonomics, physical activity and active breaks, rest, and the intake of stimulating beverages” (p. 6). Finally, regarding agile practices, the results were positive, except for the one referring to interaction with end users, in which 59.2% of respondents reported inconveniences in the execution (Niño et al., 2020).

Santos et al. (2022, p. 597) found that using active methodologies in conjunction with ICTs for assessment “contributed to comprehension, understanding, and facilitated communication, language, and the way of expressing knowledge.”

Strengthening competencies using ICTs

According to Rodriguez (2019), evaluation through ICT-mediated processes has a favorable impact on learner development, in this specific context by motivating students in a more playful and interactive way and allowing them to participate actively in the evaluation processes. This coincides with the study by Turra et al. (2022, p. 20), which found a correlation between collaborative work and the use of ICTs for assessment purposes, considering them “determining factors in the learning process”; similarly, with the findings of Burga-Falla et al. (2022, p. 433), who argue that formative assessment applied through ICTs “becomes a strategic resource that motivates learning by self-regulating student and academic well-being.”

In this regard, Aguiar and Velázquez (2018) state that it would improve quality, not only because of the evaluation mechanism but also because of the increased motivation of students through an interactive process of knowledge construction where both the student’s and the teacher’s competencies are strengthened.

Mendoza et al. (2021) conclude that the evaluative practices applied are diverse and consider different criteria to qualify student performance in terms of their integral formation.

In addition, the benefits presented by Medina et al. (2022) show that student participation in evaluation moments increased because individual and group progress was constantly observed and because students were motivated by the fact that they could use their cell phones in class.

Similarly, Maureira et al. (2020, p. 202) indicate that this assessment strategy allowed “extending the classroom work and monitoring students’ work, facilitating their role in feedback through automation and instantaneous delivery of results.”

Also, Mendoza (2020) presents as results of using this type of tools the strengthening of a personalized formative process that reinforces teaching and learning processes and promotes interculturality and interdisciplinarity—aspects that the authors consider “one of the great contributions of ICTs in the democratization of education worldwide” (p. 35).

In case of the strategies employed by Fosado et al. (2018), the implementation of a “virtual portfolio, linked to the appropriate use of other ICTs, promoted student assertiveness for decision making” (p. 213), critical participation, active collaboration, and awareness of actions: “This, in addition, served to develop teamwork, communication, management, linkage, and social responsibility competencies” (Fosado et al., 2018, p. 213). The researchers also emphasize benefits for teachers, including facilitating the design, monitoring, and learning assessment. It should also be mentioned that, for Fosado et al. (2018), virtual platforms “will be the axis that will drive professionals that our context requires and demands” (p. 213).

Regarding the benefits of implementing virtual assessment, in contrast to face-to-face evaluation, Mendoza et al. (2021) report that 37% of teachers considered that these had similar advantages. Regarding the perception of respondents about synchronous tools and their differentiation from asynchronous ones, the authors suggest that “they facilitate evaluation processes both in terms of knowledge acquisition and competency development, besides facilitating the diagnosis of preconceptions” (p. 391) and contributing to individual formative processes.

In particular, in the case presented by Guevara (2021), the use of ICTs as an assessment and teaching and learning strategy during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic was transcendental in facilitating the continuity of education under the virtual modality for those institutions that had worked more specifically in the face-to-face modality, mediating communication between the educational community (an aspect that was restricted by quarantines), approach to content, and, of course, as a tool for accessing the products elaborated by students for their respective monitoring, evaluation, and grading. This coincides with Santos et al. (2022), who found that the use of ICTs enabled student creativity and favored the development of social, cultural, and human skills.

As previously presented, these results correspond to innovative learning assessment instruments, tools, and techniques, the implementation of which at the secondary and higher education levels offers significant benefits for the members of the educational community regarding the acquisition of skills, learning, knowledge, among others; based on this, a contribution to educational quality stands out as the greatest benefit.

Discussion

This work aimed to identify innovative learning assessment strategies, techniques, or instruments used and reported in secondary and higher education institutions in the Latin American context through a narrative review of the literature. It mainly considered studies published between 2018 and 2023, which used different methodologies, both qualitative and quantitative.

First, the study examined the concept of innovative assessment that was presented clearly by the authors. According to Valverde (2017), learning assessment is considered innovative when it “has revolutionized the traditionalist approach to evaluation” (p. 75). It is characterized by being democratic; in other words, it allows the participation of all actors and implements alternative strategies to evaluate the teaching-learning process, such as portfolios, projects, and playful games, among others, that oppose traditional assessment methods such as exams and written tests. Another characteristic of innovative assessment is its qualitative nature since it transcends the measurement or numerical assessment of results toward observation with “a wider range of educational variables” (Santamaría, 2005, p. 60). In the words of Turra et al. (2022), innovative assessment distances itself from the grading function since it transcends learning. According to Santamaría (2005), some assessment strategies are part of qualitative evaluation and thus are also alternative or innovative. For their part, Zhinín et al. (2021) consider learning assessment as innovative when it seeks to train agents of change, innovation, and projection, achieving this through practices that engage initiative and creativity. This seems timely given the constant changes in the society in which education takes place, seeking to adjust to the learners’ needs, interests, or potential to develop the skills and knowledge necessary to face the challenges of today’s world.

However, innovation sometimes gets misunderstood when traditional assessment strategies are taken to learning environments in digital media and labeled as innovative; this is evident in the studies presented by Mendoza et al. (2021) and Medina et al. (2022). Although the implementation of ICTs provides new possibilities and tools for assessment, the simple transfer of traditional assessment tools to a digital environment does not necessarily make them innovative. If the tools implemented do not imply a reconsideration and adaptation of traditional assessment methods to take full advantage of the possibilities offered by technology, they should not be considered innovative assessments; hence comes the importance of training in the proper use of assessment mediated by digital environments (Burga-Falla et al., 2022).

Instruments like resource delivery, which include the elaboration of collages, memes, comics, or others, allow students to demonstrate their learning in more authentic and relevant ways while also encouraging creativity and critical thinking (Alvarez, 2019; Gaete, 2021). The strategies grouped in inquiry techniques include implementing team projects, case studies, oral defenses, and co-assessments and facilitating feedback and support to students, which can lead to a more exciting and enriching learning environment. This is confirmed by Kaim et al. (2021), who argue that these instruments encourage students to develop competencies such as teamwork, feedback, decision-making, and conflict management, in addition to enhancing the development of their autonomy in knowledge construction.

In accordance with this, Delgado and Zambrano (2021) suggest that such strategies make students feel satisfied with the results, allowing teachers to resolve doubts and fill the gaps that appear. However, not all studies report positive benefits, as an evident commitment is necessary on the students’ part. Cunha et al. (2019) state that students must be responsible for individual preparation before group work, a fundamental step that, if not carried out, may negatively influence individual and group performance.

For their part, the strategies grouped in active methodologies, as mentioned by Gutiérrez-Saldivia and Riquelme (2020), become an assessment that is sensitive to the needs and processes of students, being a primary means for communication and reflection on learning and that covers all phases of the learning cycle (Casanova, 1995). Regarding ICT-mediated strategies, students showed increased motivation and participation in classes and during the evaluation, according to Medina et al. (2022) and Santos et al. (2022). The authors also agree that these strategies enrich learning and favor the development of competencies and skills.

In agreement with the above, Mendoza (2020) assures that ICTs “make it possible to promote intercultural and interdisciplinary characteristics, constituting one of the great contributions of ICTs in the democratization of education worldwide” (p. 7).

According to Fosado et al. (2018), strategies involving ICTs also foster assertiveness for decision-making, “critical participation, awareness of actions, and active collaboration” (p. 213). Despite this, their design and implementation require commitment, time, and training for teachers and students not accustomed to their use (Fosado et al., 2018). Guevara (2021) agrees with this and states that, although students considered themselves “digital natives,” they had difficulties handling the assignments since what they had to navigate was not social networks but educational platforms, applying a set of digital skills that they had not yet developed. Similarly, Burga-Falla et al. (2022) argue that “despite satisfaction with continuous online assessment, it was discovered that many students were not prepared for this type of education” (p. 433), given that there are places where internet access is deficient or the training provided is not sufficient.

The analysis of these articles additionally revealed that there are few publications available on innovative assessment at the secondary education level, which may well be due to little research on this topic and level, the absence of innovative assessment techniques in this context, or, as Tagle et al. (2021) state when addressing other research, to an emphasis on preparation for state or international tests, which may lead to a traditional approach to teaching and assessment. Although a higher number of research studies have been found at the higher education level, we agree with Santos et al. (2022), who consider that “in higher education, there are still few studies that address assessment strategies,” identifying additionally that innovation in this aspect is even less studied. Similarly, we agree with the worrisome observation of Stieg et al. (2022) about the need “to conduct more studies in countries such as Brazil, Colombia, Cuba, and Chile, which assume as a locus of research the assessment practices carried out by physical education teachers in secondary education” (p. 811), to which we can well add countries such as Paraguay, Uruguay, Argentina, Costa Rica, Peru, Puerto Rico, Dominican Republic, Honduras, Panama, Nicaragua, Guatemala, El Salvador, and Ecuador, among others, as well as a research focus on innovative learning assessment strategies in secondary and higher education levels.

At the secondary education level, it is important to apply innovative assessment tools that foster critical thinking, creativity, and problem-solving, which constitute essential skills for success later in higher education and professional life. These may include conducting interdisciplinary projects, solving real-world problems, creating creative products, and using digital technologies. Such strategies allow students to apply acquired knowledge in concrete situations and develop practical skills that will be useful to them in the future. In the words of Díaz (2012), “helping young people to understand and develop skills to face the changes involved in starting higher education is an extremely valuable objective within the framework of secondary education” (pp. 250-251).

One of the aspects appearing in this study allows estimating difficult conditions as an opportunity for improvement and innovation. Such is the case of the COVID-19 pandemic, which, despite being an unprecedented challenge for education, also generated needs and occasions to design new ways of evaluation. An example of this is the research conducted by Mendoza (2020), Guevara (2021), and Santos et al. (2022), which highlights the use of online tools and technologies, the adoption of inclusive and adaptive methodologies, and greater collaboration between teachers and students, to mention just some of the ways in which the pandemic has driven change in assessment, which in turn has contributed to reducing stress, anxiety, and other characteristics of traditional evaluation.

By applying innovative learning assessment strategies, the analyzed articles suggest that innovation in assessment can foster creativity and critical thinking in students. Assessments that require students to apply what they have learned to real situations or solve complex problems can challenge their thinking and help them develop valuable skills they can employ beyond the classroom. This helps create a more exciting and enriching learning environment for students, which, in turn, increases motivation and engagement. Consequently, better information retention and, in general, learning acceptance can be achieved. Finally, these innovative practices can strengthen the competencies of both teachers and students and contribute to improving the quality of education (Aguiar & Velázquez, 2018), which is in tune with Santos et al. (2022), who suggest, referring to Freire’s contributions, that assessment is an opportunity to transcend didactics and take part of the construction or production of knowledge.

For these benefits to be increasingly significant, teacher training is required, among other aspects. Gordón et al. (2021) point out that this should involve the management and application of ICTs and strengthening team and collaborative work, creativity, and educational inclusion. In addition, innovative assessment strategies could be added as part of the training to correct practices and perceptions that continue to point to traditional evaluation as the most common type in Latin America, as can be inferred from Santos et al. (2022) and Gárgano (2020).

Conclusions

The analyzed articles evidenced a shared view among the authors on assessment as a fundamental element in any learning process. This is because evaluation makes it possible to identify the knowledge acquired, the skills developed, and, in general, the effectiveness of the educational process. However, these evaluation characteristics can be potentiated or diminished according to the strategies, tools, instruments, or techniques implemented or due to a lack of knowledge and inadequate application.

Evaluation through traditional assessment strategies can limit the potential of students and may not adequately reflect learning in an ever-changing world. Thus, innovation in assessment is crucial in today’s education, given that it is necessary to foster the development of students’ potential.

New technologies, methodologies, and approaches can help create more meaningful assessments, given that these allow students to demonstrate their learning more authentically and relevantly and constitute opportunities in the teaching-learning process. It has also been shown that by including varied assessment strategies, students are more motivated, and this improves their understanding, learning, and the development of soft skills.

The analysis of the included studies showed that there are more reports on implementing innovative learning assessments at the higher education than the secondary education level. However, regarding those with a similar exploration to ours, the scarcity of studies on learning assessment in Latin America stands out. In addition, the most used strategies for assessment considered innovative are the employment of ICTs, followed by inquiry techniques, active methodologies, and, to a lesser extent, assessment through resource delivery. The highlighted tools include digital portfolios, creating resources such as posters, comics, graphic diagrams, peer assessment (co-assessment), project-based and team-based learning, oral defense, and case studies.

Two questions emerge from the research results: a) how do innovative assessment strategies affect the academic performance of students? and b) what impact does the implementation of innovative learning assessment strategies in secondary education institutions generate at the higher education level? To answer these questions, some possible lines of research on innovative learning assessment are suggested based on the exploratory study presented here. One could examine how to use technology and online learning to develop new innovative assessment forms. Another research area could explore how innovative assessment strategies can be used to improve student performance in secondary education and their impact on training at the higher education level. Research could focus on the effect on teacher and student motivation of involving problem-solving, critical thinking, and creativity in evaluation, skills that are increasingly relevant in an ever-changing and demanding world. Overall, research on innovative assessment could significantly impact how learning is measured and how students prepare for success in higher education and professional life.

References

Aguiar, B., & Velázquez, R. (2018). Aproximación teórica al estudio de las tecnologías y su importancia en el proceso de evaluación universitaria. Revista Cubana de Educación Superior, 37(3), 1-19.

Alvarez, L. (2019). Una experiencia innovadora de evaluación en un aula de secundaria de la ciudad de Santa Fe-Argentina: Sentidos y prácticas. Clío & Asociados. La Historia Enseñada, 29, 152-160. https://doi.org/10.14409/cya.v0i29.8798

Backhoff, E., Andrade, E., Sánchez, A., & Peon, M. (2007). El aprendizaje en tercero de primaria en México: español, matemáticas, ciencias naturales y ciencias sociales. Mexico City: Instituto Nacional para la Evaluación de la Educación. https://www.inee.edu.mx/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/P1D220.pdf

Burga-Falla, J.-M., Huamán-Romaní, Y.-L., Soria-Ruiz, N.-S., Raymundo-Balvin, Y., & Franco-Sánchez, M.-K. (2022). Sistemas aplicados a la evaluación formativa: ¿Cumplen o no los docentes en la educación secundaria, Perú? Revista Ibérica de Sistemas e Tecnologias de Informação, E53(10/2022), 424-436.

Carbonell, J. (2002). La aventura de innovar: El cambio en la escuela (Vol. 7). Madrid: Morata.

Caro, M., Calero, C., Rodríguez, A., Fernández-Medina, E., & Piattini, M. (2005). Análisis y revisión de la literatura en el contexto de proyectos de fin de carrera: Una propuesta. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/251671565_Analisis_y_revision_de_la_literatura_en_el

_contexto_de_proyectos_de_fin_de_carrera_Una_propuesta

Casanova, M. (1995). Manual de evaluación educativa. Madrid: La Muralla.

Castillo, S., & Cabrerizo, J. (2010). Evaluación educativa de aprendizajes y competencias. Madrid: Pearson Educación S. A. https://gc.scalahed.com/recursos/files/r161r/w24689w/Evaluacion_educativa.pdf

Cunha, C., Ramsdorf, F., & Bragato, S. (2019). Utilização da Aprendizagem Baseada em Equipes como Método de Avaliação no Curso de Medicina. Revista Brasileira de Educação Médica, 43(2), 209-215. https://doi.org/10.1590/1981-52712015v43n2RB20180063

Delgado, M., & Zambrano, L. (2021). Técnicas creativas para la evaluación del aprendizaje en los estudiantes de bachillerato. ReHuso: Revista de Ciencias Humanísticas y Social, 6(3), 40-52.

Díaz, C. (2012). La política de articulación entre la educación media y la superior. El caso de los programas de la Secretaría de Educación de Bogotá. Investigación y Desarrollo, 20(2), 231-253.

Esquivel, J., Ferrer, G., Ravela, P., Valverde, G., Wolfe, R., & Wolff, L. (2006). Sobre estándares y evaluaciones en América Latina. Santiago de Chile: Preal. http://www.grade.org.pe/upload/publicaciones/archivo/download/pubs/PA_SobreEstandy

EvaluacionesenAmericaLatinaedityarto.pdf

Fernández Santos, A. (2019). Evaluando la evaluación de los aprendizajes. San Salvador: Universidad Francisco Gavidia. http://ri.ufg.edu.sv/jspui/bitstream/11592/9711/1/Evaluando%20la%20evaluacion%20de%20los%

20aprendizajes.pdf

Fosado, R., Martínez, A., Hernández, N., & Ávila, R. (2018). El portafolio virtual como una herramienta transversal de planeación y evaluación del aprendizaje autónomo para el desarrollo sustentable. RIDE Revista Iberoamericana para la Investigación y el Desarrollo Educativo, 8(16), 194-215. https://doi.org/10.23913/ride.v8i16.338

Gaete, R. (2021). Evaluación de resultados de aprendizaje mediante organizadores gráficos y narrativas transmedia. Revista de Estudios y Experiencias en Educación REXE, 20(44), 384-407. https://doi.org/10.21703/0718-5162.v20.n43.2021.022

Gárgano, S. (2020). Análisis de las estrategias de evaluación de los aprendizajes de las materias de Fisiología Humana y Aplicada de las Carreras de Educación Física. Revista Electrónica Interuniversitaria de Formación del Profesorado, 23 (3), 201-215. https://doi.org/10.6018/reifop.366371

Gordón, M., Gordón, D., & Revelo, R. (2021). Estrategias didácticas para el proceso de enseñanza-aprendizaje en tiempos de pandemia COVID-19. Conrado, 17(81), 226-235.

Guevara, A. (2021). Evaluación de los aprendizajes en tiempos de COVID-19: el caso del estado de Chihuahua. Revista Electrónica de Investigación Educativa, 23(e17), 1-16. https://doi.org/10.24320/redie.2021.23.e17.4335

Guirao, S. (2015). Utilidad y tipos de revisión de literatura. Ene, 9 (2). https://doi.org/10.4321/S1988-348X2015000200002

Guirao-Goris, J., Olmedo, A., & Ferrer, E. (2008). El artículo de revisión. Revista Iberoamericana de Enfermagem Comunitária, 1(1), 6.

Gutiérrez-Saldivia, X., & Riquelme, E. (2020). Evaluación de necesidades educativas especiales en contextos de diversidad sociocultural: opciones para una evaluación culturalmente pertinente. Revista Brasileira de Educação Especial, 26(1), 159-174. https://doi.org/10.1590/s1413-65382620000100010

Kaim, C., Matos, B., Araújo, M., Raimondi, G., & Borges, D. (2021). Avaliação por pares na educação médica: Um relato das potencialidades e dos desafios na formação profissional. Revista Brasileira de Educação Médica, 45(02), 6. https://doi.org/10.1590/1981-5271v45.2-20200263

Maureira-Cabrera, O., Vásquez-Astudillo, M., & Garrido-Valdenegro, F. (2020). Evaluación y coevaluación de aprendizajes en blended learning en educación superior. Revista de Educación, 15(2), 190-206. https://doi.org/10.17163/alt.v15n2.2020.04

Medina, N., Delgado, J., & Guerrero, R. (2022). Socrative como herramienta para la evaluación y aprendizaje de Fundamentos Matemáticos en el estudiantado universitario. Revista Actualidades Investigativas en Educación, 22(1), 1-29. https://doi.org/10.15517/aie.v22i1.49065

Mendoza, H. (2020). Modelos de redes neuronales artificiales, como sustento evaluativo al crecimiento pedagógico virtual en Educación Superior. Educación Superior, 7(2), 25-36.

Mendoza, H., Burnano, V., & Valdivieso, M. (2021). Prácticas evaluativas de profesores universitarios colombianos en entornos virtuales. Revista de Ciencias Sociales, 27(4), 379-395.

Niño, J., Arboleda, W., & Anaya, R. (2020). Fortaleciendo la formación integral de ingenieros de sistemas a través de proyecto integrador. Encuentro Internacional de Educación en Ingeniería, ACOFI, August 2020. https://doi.org/10.26507/ponencia.738

Page, M., McKenzie, J., Bossuyt, P., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T., Mulrow, C., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J., Akl, E., Brennan, S., Chou, R., Glanville, J., Grimshaw, J., Hróbjartsson, A., Lalu, M., Loder, E., Mayo-Wilson, E., McDonald, S., McGuinness, L., & Alonso-Fernández, S. (2021). Declaración PRISMA 2020: Una guía actualizada para la publicación de revisiones sistemáticas The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Revista Española de Cardiología, 74(9), 790-799. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.recesp.2021.06.016

Reinoso-González, E., & Hechenleiter-Carvallo, M. (2020). Percepción de los estudiantes de kinesiología sobre la innovación metodológica mediante flipped classroom utilizando Kahoot como herramienta de evaluación. Revista de la Fundación Educación Médica FEM, 23(2), 63-67. https://doi.org/10.33588/fem.232.1044

Rodríguez, L. (2019). Implementación de un ava como estrategia para mejorar el proceso de evaluación de las artes plásticas en la media académica (grados 10° y 11°) del colegio Caldas-Villavicencio. [Unpublished Master’s thesis]. Universidad de La Sabana.

Romero, I., Gómez, P., & Pinzón, A. (2018). Compartir metas de aprendizaje como estrategia de evaluación formativa. Un caso con profesores de matemáticas. Perfiles Educativos, XL(162), 117-137. https://doi.org/10.22201/iisue.24486167e.2018.162.58632

Santamaría, M. (2005). ¿Cómo evaluar aprendizajes en el aula? San José, Costa Rica: Editorial Universidad Estatal a Distancia.

Santos, S., Fernandes, M., Caranhato, S., & Do Carmo, S. (2022). Avaliação da aprendizagem na educação superior: Cooperação e inovação. Revista Meta: Avaliação, 14(44), 580-602. https://doi.org/10.22347/2175-2753v14i44.3766

Solórzano, F., & García, A. (2016). Fundamentos del aprendizaje en red desde el conectivismo y la teoría de la actividad. Revista Cubana de Educación Superior, 35(3), 98-112.

Stieg, R., Fernández, C., Magaña, E., & Benito, L. (2022). Evaluación para el aprendizaje en educación física en la enseñanza primaria y secundaria: un análisis comparativo de la producción académica en Latinoamérica y España (2000-2021). Revista Meta: Avaliação, 14(45). https://doi.org/10.22347/2175-2753v14i45.3817

Taccari, D. (2009). Uso de la Clasificación Internacional Normalizada de la Educación (CINE ‘97) para la presentación de estadísticas e indicadores educativos comparables. Cuaderno SITEAL 03. Buenos Aires.

Tagle, T., Díaz, C., Alarcón, P., Ramos, L., Quintana, M., & Etchegaray, P. (2021). Evaluación y prácticas de estudiantes y profesores noveles chilenos en planificación y enseñanza. Revista de la Educación Superior RESU, 50(198), 131-154.

Tobón, S., Pimienta, J., & García, J. (2010). Secuencias didácticas: Aprendizaje y evaluación de competencias. Naucalpan de Juárez, Edo. de México: Pearson Educación S. A.

Turra, Y., Villagra, C., Mellado, M. E., & Aravena, O. (2022). Diseño y validación de una escala de percepción de los estudiantes sobre la cultura de evaluación como aprendizaje. Relieve, 28(2), 1-25. https://doi.org/10.30827/relieve.v28i2.25195

Valverde, X. (2017). La evaluación tradicional vs. Evaluación alternativa en la FAREM-Carazo. Revista Torreón Universitario, 6(15), 75-82. https://doi.org/10.5377/torreon.v0i15.5563

Yepes-Nuñez, J., Urrútia, G., Romero-García, M., & Alonso-Fernández, S. (2021). Declaración PRISMA 2020: Una guía actualizada para la publicación de revisiones sistemáticas. Revista Española de Cardiología, 74(9), 790-799. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.recesp.2021.06.016

Zhinín, J., Viteri, B., & Ayala, L. (2021). Sistema de evaluación integral para un aprendizaje complejo en Derecho. Conrado, 17(78), 276-281.

.........................................................................................................................................................

Gustavo A. Pherez

PhD in Educational Sciences, Universidad del Rosario, Argentina. His topics of interest focus on Educational Management and Learning Assessment. Recent publications: Pherez, G., Vargas, S. & Jerez, J. (2018). Neuroaprendizaje, una propuesta educativa: herramientas para mejorar la praxis del docente. Civilizar. Ciencias Sociales y Humanas, 18 (34), 149-166. https://orcid.org0000-0002-6515-0240

Nury N. Garzón

Specialist in Education. Her research interests include learning assessment, the use of technology in the classroom, and the implementation of artificial intelligence in education. Recent publications: Garzón-Aguiar, N. (2015). “Rana dorada: un caminante hacia la extinción” (artículo de opinión). Memorias de la Conferencia Interna en Medicina y Aprovechamiento de Fauna Silvestre, Exótica y no Convencional 11, no. 1 (julio 17, 2015): 23–26. https://orcid.org/0009-0009-1992-2009

Edna K. Conde

Specialist in Education, Systems Engineer. Her interests focus on software development, artificial intelligence, and the implementation of technology in education. Recent publications: Conde, E. & Salinas, D. (2019). Una propuesta de modelo dinámico sistémico del conflicto armado en Colombia y sus consecuencias [Universidad Autónoma de Bucaramanga]. https://orcid.org/0009-0009-1105-2651

Jorge Hoyos

PhD Candidate in Music, MA in Music. His topics of interest revolve around music education, timbre, and ethnomusicology. Recent publications: Hoyos, J. & Ovalles, A. (2020). Jajuit: El papel del canto en la comunidad indígena Jiw de Barranco Colorado, Colombia. In Invigaestción en filosofía en tiempos cambiantes (pp. 88-103). Medellín: Sello Editorial Universitario Americana. https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7345-7867

* The article was part of a research prepared as a requirement for the degree of Specialist in Education at Corporación Universitaria Adventista, Medellín, Colombia. It was not funded and we have no conflicts of interest to report. Correspondence regarding this article should be addressed to Edna Conde (docente.econdev@unac.edu.co). The article was translated with funding from the Ministry of Science, Technology and Innovation, through the Patrimonio Autónomo Fondo Nacional de Financiamiento Francisco José de Caldas fund and the Office of the Vice President for Research and Creation at Universidad de los Andes (Colombia). The article was originally published in Spanish in the issue 14-2 of Voces y Silencios: Revista Latinoamericana de Educación.